|

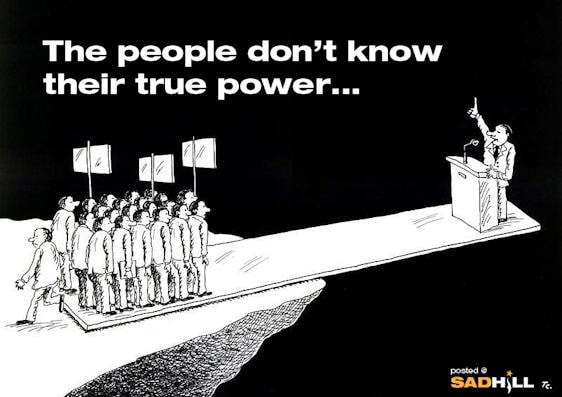

The basic logic of democracy is that the people are the final authority in politics. This is the principle of popular sovereignty: that the true sovereign is no high official, no oligarch, no general, no king, but the people. This is of course why we have elections to hold our leaders accountable: before we get to higher-level arguments about representation, responsible governance, or the common good, the first thing that democracy means is that the people are the final authority, who can peacefully overturn their government and put a different one in its place. Until recently, I had thought that everyone in our society basically bought into this premise, with very few exceptions. Yes, this basic conception of democracy is one of the fundamental tenets of the Enlightenment that is hegemonic in our culture today.[i] And yes, if you ask people in the abstract, people will say they believe in popular sovereignty. But it strikes me how often people get it backwards and invert this relationship of accountability. I’ve been voting third party in presidential elections for a while now. This is a decision that I have always given much deliberation in each election. The point here is not my reasons for voting third party, but how others respond when I tell them this. “Voting third party? But why would you throw your vote away like that?” “I don’t think either major candidate has earned my vote, and I’m voting for a candidate who has.” After some discussion of the strategic pros and cons of voting third party, which is typically premised on the idea the both of us have the same goals politically, the conversation then frequently devolves into a mild but persistent chiding of me, and an effort to convince me to vote, as a matter of strategy, for the Democrat. “Well, if you don’t vote for Biden, isn’t that kind of like voting for Trump? Or at least effectively like half a vote for Trump?” I won’t deal here with arguments about voting for an evil that is lesser than another evil, or about how much the two parties differ, or about voting “against” a candidate instead of “for” a candidate, or any of the usual suspects in an argument about tactical voting. These, after all, are tough questions, and a matter of judgment for any given voter. Here I simply want to point to an assumption that sneaks into these discussions: that I, as a voter, have an obligation to support one of the two major candidates, and if I don’t, I am letting the better candidate down. Some people will go so far as to actively shame nonbinary voters for this. When that politician loses, as Hillary Clinton did in 2016, it is not her fault for failing to appeal to more voters, as she should have, but the voters’ fault—they failed to vote for her, as they should have. It was not her responsibility to earn your vote, but your responsibility to vote for her, the reasoning goes. This logic became just another device in the service of removing the blame from Clinton and her lackluster campaign. The opposite party’s voters are not typically chastened like this. I suppose this is because they are perceived to have different political values, goals, and worldviews, whereas I, who “should” be voting Democrat, am presumed to share these things with the Democratic voter I am speaking with. In their minds, I imagine, Republicans don’t deserve this scorn because, even though they are on the opposing team, at least they are playing by the rules and voting for a candidate that won’t “waste” their vote. I, however, am perceived to be on the same team, but I’m sabotaging all their efforts to win the game by not playing it with their optimized strategy. Enemy soldiers may get fired at, but scorn is reserved for deserters. From the perspective of the loyal Democrat, the problem is that I am not voting as I “should”. So, I should be pressured into doing so. What you might notice here is how voter shaming turns upside-down the basic idea of democracy: it holds voters accountable to politicians rather than the reverse. Instead of expecting politicians to earn our votes, we expect each other (when categorized in the appropriate box) to support our politicians. Instead of politicians owing us policies that will work in our interests, we owe politicians votes that will help them achieve their ambitions. In some cases, this voter shaming is only a side dish presented alongside a persuasive argument based on policy differences between the candidates, and that can be part of a healthy discussion on how (and whether) we should vote. I am certainly not arguing against interpersonal debates about how to vote. But in many cases the shame is the main course: you should vote for the Democrat because how dare you. Even worse, it is sometimes claimed that exercising your right to freely vote for whom you choose by voting third-party is somehow a privilege that oppressed voters don’t have the luxury of indulging in. This is clearly untrue, but the more important point is that when voting itself is characterized as a privilege, rather than as a right, the antidemocratic nature of this line of argument is undeniable. After all, when something is a privilege and not a right, it is granted from above and can be taken away under certain conditions. Where does this urge to blame voters rather than candidates come from? Why is there so much voter shaming going on, when we should all be candidate-shaming instead? Maybe social media has set us all up as targets to be critiqued for our politics. Twitter and Facebook have certainly made punching down at least as easy as punching up. It sometimes even seems like the business model of social media is meant to keep us hooked on public shaming and cancellation as a modern ritual of human sacrifice. Or maybe we’ve learned to be fans rather than citizens, and we’ve come to believe that our role is to root for our electoral team to score as many points as it can. Whatever its sources, we can see this logic not just when it comes to elections, but in higher levels of politics as well. In early January 2021, even the most progressive members of Congress balked at a proposal put forward by commentator Jimmy Dore to withhold their votes for Nancy Pelosi as Speaker of the House unless Pelosi promises them a floor vote on Medicare for All. For instance, despite campaigning on the promise of getting a vote on Medicare for All, and despite her repeated claims that the Democratic party needs new leadership, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (along with everyone else in “the squad”) refused to even threaten to withhold her vote.[ii] AOC argued that she didn’t want to risk getting a Republican elected speaker of the House. At first blush this seems to be an understandable concern, but notice what’s already happened here. What assumptions have already been made in order to make these arguments? First, AOC has assumed that if the lone Democratic nominee were to lose, then the Republican leader will automatically win. It turns out, however, that a Speaker from the GOP minority was never really a possibility, as any Republican candidate would need the votes of multiple Democrats. The rules for the election of the Speaker of the House don’t recognize the two-party duopoly. In other words, unlike the presidential contests where we are habituated to, this was not a lesser evil election, but a contest to see which candidate—no matter their party—could earn a majority of votes in the House. No Speaker would be elected unless and until someone could get that majority, and it was never likely to be a Republican. Pelosi getting fewer votes does not translate into GOP leader Kevin McCarthy getting closer to a majority of House members. Second, AOC assumed that Pelosi would say no. This in itself says a lot about Nancy Pelosi and what House progressives think of her. If they deemed Pelosi worth voting for in the first place, wouldn’t it be possible that she would at least entertain the idea of a floor vote on Medicare for All to shore up the support she needs to be elected Speaker again? Conversely if you are confident that should would sacrifice her Speakership just to ensure that Medicare for All did not get a floor vote—as AOC implied in her tweets—how could she possibly be worth supporting? If that is your expectation of Pelosi’s response, then the sensible move is to vote against her, not for her. AOC’s using the fact that Pelosi would never allow a floor vote on Medicare for All as a reason to vote for her is an astonishing feat of intellectual gymnastics. Third, AOC assumed that, should Pelosi say no, the House progressives who withheld their votes will be responsible for her losing her Speakership. And here again we see the logic of inverted democracy: when subordinates refrain from supporting a leader, the leader is not deemed to have failed her supporters, but vice versa. If Pelosi loses her position as Speaker it will not be because of such a simple demand being made by House progressives, but rather because of her refusal to concede to that demand. Pelosi losing the Speakership would be what it looks like when a constituency holds its leadership accountable. Pelosi would have failed, not the progressives who held her up to such a minimal standard. So, AOC’s argument was based on false assumptions: a Republican speaker was never a real possibility, Nancy Pelosi probably would not have sacrificed her Speakership just to prevent a floor vote on Medicare for All, and if she had, it would have been her own fault, not the fault of those who refused to support her without such a promise. But even if AOC and other progressives realized all of this, there were plenty of reasons to support Pelosi, even if they aren’t the most noble of reasons. It just so happens that Pelosi wields enormous fundraising power, as one of the richest and most well-connected (read: corrupt) members of Congress, and such informal powers, combined with the Speaker’s ability to mete out punishments and rewards in the form of committee assignments, have allowed her to scare anyone away from stepping forward as an alternative candidate from within the Democratic caucus—including the most vocal progressives in “the squad”, like Ocasio-Cortez herself. In the absence of such a challenger, the choice appeared to be between Pelosi or someone possibly even worse. So, for House progressives, it was either Pelosi or the wrath of Pelosi. When presented with such a restricted choice, there is no power—no freedom—in choosing either A or B. One must have the power to say no. The power to say no is central to the most basic democratic processes. Imagine a legislature that, when voting on legislation, structures the decision as follows: vote for bill A or bill B, and if you don’t like either, you should vote for the one you dislike less. When Congress—or any legislative body, for that matter—passes legislation, it does not use this model, but instead votes on a single bill, up or down, yea or nay. No is always an option. If no is not an option in the choice you have before you, your vote is not an exercise of sovereignty. In such cases, that sovereignty has already been exercised by whoever put the choice in front of you. Third-party voters (and many abstainers) are those who have come to grips with their power to say no. No, this choice is not good enough. No, I will not be coopted into validating the corrupt elite processes that put these oligarchic puppets on the ballot. Because of the Democrats’ reduced majority in the House, a handful of progressives had the rare opportunity to exercise their power to say no to Nancy Pelosi in order to force a vote on Medicare for All in the midst of a deadly pandemic. If Pelosi had refused to accede to their demand for a vote (only a vote!) and lost the speakership, then she would only have proved beyond a doubt that it is indeed time for new leadership. Yes, it would have been confrontational, even adversarial—it would have been playing hardball. But the power of the vote is that it must be earned, and leaders will not be made to earn your vote unless you are willing to walk away. There is no other way politicians can be held accountable to the people: if we are to have sovereignty, we must be capable of saying no. Citations [i] See, e.g. Hobbes’ Leviathan, Locke’s Second Treatise on Government, and Rousseau’s The Social Contract. Benjamin Franklin boiled it down like this: “In free governments, the rulers are the servants and the people their superiors and sovereigns.” Ralph Ketchum, ed., 2003, The Political Thought of Benjamin Franklin, Hackett Publishing, p. 398. [ii] All of the members of “the squad” ended up voting for Pelosi without extracting any promises on a vote for Medicare for All.” About the Author:

Ben Darr teaches politics and international studies at Loras College, in Dubuque, Iowa. He went to college at Northwestern College in Orange City, Iowa, and earned his Ph.D. in political science at the University of Iowa. His interests include global inequality, and U.S. foreign policy. He is currently working on a book on spectator sports as a model of neoliberal politics.

1 Comment

Darios@

1/22/2021 04:50:06 pm

excellent job, much thanks.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed