|

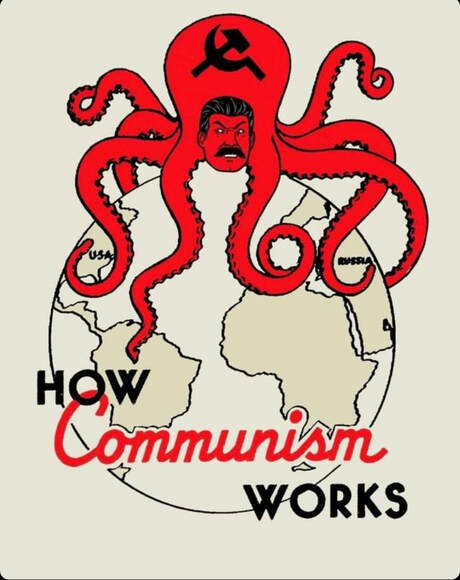

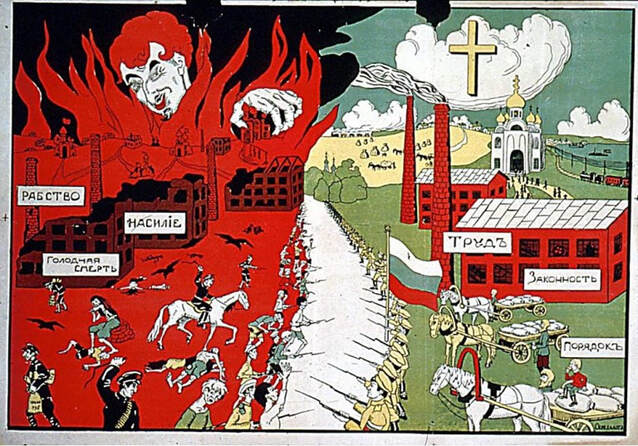

Even before 1917, the year of both the Balfour Declaration and the Russian Revolution, Zionism and Marxism had already had a long and complex relationship. While the two movements had been competing for many years for membership among Europe’s Jewish population, particularly its intellectuals, many prominent Zionist leaders and theoreticians considered themselves socialists. While this feud had largely been confined to Europe, it would have major implications for Palestine. With the Balfour Declaration and Britain’s support for a “Jewish national home” in Palestine, Zionist interests dovetailed with the anti-communist crusade of the British empire. The anti-communist utility of Zionism formed a major part of the ideological justification for the Balfour Declaration and helped shape British policy during its mandate over Palestine. In this essay, I will explore this relationship and the role it played in Britain’s decision to support Zionism and its governance over Palestine in the early 1920s. Prior to 1917, Zionism and Marxism were two of the most popular political ideologies among European Jewish intellectuals. So much so that many, like Nahman Syrkin, had attempted to synthesize Marxism and Zionism into a coherent Socialist-Zionist ideology.[1] On the other hand, most Marxists denounced Zionism, particularly the liberal strain of Theodore Herzl, as reactionary and nationalistic.[2] Marx himself contended that the solution to “the Jewish problem” would not come through national emancipation but with change in the material basis of society. Through Christian discrimination against Jews in manual labor, they had been pushed into bourgeois economic activity, such as moneylending. Through the emancipation of people from capitalist economic structures, Jewish people would also be freed from the bourgeois economic activities they had been forced to adopt and become equal members of a socialist society.[3] This would remain the basis for much of the proceeding 19th century Marxist thought on Jewish issues and hardly corresponded with Zionist visions of a Jewish state in Palestine. The year 1917 brought major milestones for both movements that would bring them to an impasse and intimately connect Zionists, the Soviet Union, and Palestine for the rest of the century. A significant Jewish population lived in Eastern Europe and the Russian Empire, which made the region an important location for Zionist activities.[4] Under the late-Tsarist government, Russian Zionists hatched a deal that gave them semi-legal status in exchange for diverting Russian Jews away from revolutionary parties.[5] The destruction of the Russian monarchy and the emergence of an anti-Zionist Bolshevik government with its own solution to the emancipation of Jewish people ended this cozy situation and created a new challenge for Zionist leaders that would reappear throughout the 20th century. However, it also created a convenient boogeyman with which Zionist leaders could frighten imperial powers they courted as patrons for a colony in Palestine. *Political cartoon, 1919 Few governments reviled and feared communists as much as the British Empire. While British officials disliked communism for many of their own reasons, a common one among them had to do with their feelings towards Jewish people. While attitudes varied among British people and officials, a common belief was that Jewish people or “global Jewry” wielded disproportionate global influence through control of financial and media institutions and coordination among its globally dispersed population.[6] For instance, some in the British press and government maintained the Jews and “crypto-Jews” played a major role in promoting the 1911 Young Turk Revolution in Turkey through their control of the press and secret societies.[7] Illustrating British views of “global Jewry”, a London Times article called on “The enlightened and humanitarian Jews” of England and similar countries to exert pressure on Turkish Jews to correct their behavior.[8] This was by no means a fringe opinion. David Lloyd George, UK Prime Minister from 1916-1922, was himself a committed Zionist. And, while Lloyd George had his own Christian theological reasons for supporting Zionism, a major point of consideration for him was his belief in the influence of the “Jewish race”. In secret remarks made before the 1937 Peel Commission on Palestine, Lloyd George made this belief plain stating, “[Jewish people] could either hinder us or help us very materially, because they have communities all over the world and they are a dangerous people to quarrel with, but they are a very helpful people if you can get them on your side.”[9] British officials like Lloyd George believed that this global influence could be decisive in their battle with Germany during World War I, as the British feared the Central Powers may beat them to the punch.[10] As the London Times lamented, “Do our statesmen not see how valuable to the Allied cause would be the hearty sympathy of the Jews throughout the world which an unequivocal declaration of British policy might win?”[11] The Times also warned, “Germany has been quick to perceive the danger to her schemes and to her propaganda that would be involved in the association of the Allies with Jewish national hopes, and she has not been idle in attempting to forestall us.”[12] One of these methods, supposedly, was German propaganda encouraging pacifist tendencies among the Russian population, which British media linked to the Bolsheviks and the Russian Revolution. The London Times reported that Lenin and other prominent Bolsheviks were funded by the German government and proclaimed the Revolution was “Organized and financed by Germany.”[13] Consequently, the Bolshevik Revolution had “naturally been directed towards the goal desired by Germany: the conclusion of a separate peace, involving complete surrender of Russia’s independence, politically and economically.”[14] Additionally, many in the British government and media feared American public opinion turning against the war, and they believed American Jews could impact this through their supposed control of American media and financial institutions.[15] Thus, it is no surprise that Lloyd George declared to the Peel Commission, “we had every reason at that time to believe that in both countries the friendliness or hostility of the Jewish race might make a considerable difference.”[16] For their part, Zionist leaders encouraged this belief in Jewish influence and sought to associate Zionism with the world’s Jewish population generally. Chaim Weizmann, who was a prominent Zionist leader with connections to British officials, worked to give off this impression. Frequently, in international private correspondence which he undoubtedly knew would be read by the British censor, Weizmann wrote as if directing the machinations of a global network capable of exerting significant influence in both America and Russia.[17] This had the double effect of confirming British assumptions of Jewish global influence as well as Zionist affirmations that Jewish people constituted a nation despite being dispersed across the globe. Further, it appeared to show Zionists composed most of that nation. In response to a letter written opposing the Balfour Declaration printed by the London Times, Zionist benefactor, Lord Rothschild, claimed the authors represented “a mere fraction of Jewish opinion of the world” and sought to “interfere in the wishes and aspirations of by far the larger mass of the Jewish people.”[18] This did have a great affect on British decision making to approve the Balfour Declaration. As historian Tom Segev points out, “Weizmann’s principal achievement was to create among British leaders an identity between the Zionist movement and ‘world Jewry’… Yet none of it was true… Most Jews did not support Zionism; the movement was highly fragmented, with activists working independently in different European capitals. Weizmann had absolutely no way of affecting the outcome of the war. But Britain’s belief in the mystical power of ‘the Jews’ overrode reality.”[19] *Chaim Weizmann with Lord Balfour in Palestine, 1925 This belief in global Jewish influence was taken even further by other members of the British government, public, and media who proposed a link between the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and a global Jewish conspiracy to overthrow the Christian world. This theory arose as a result of Christian theological traditions associating Jews with the antichrist and the millenarian reaction of British Christians to the carnage of the first world war and the Russian Revolution.[20] This was also fueled by a widely held association between Bolshevism and Judaism among British people. The connection between Communism and Judaism in the British mind resulted from the prominence of Jewish Bolsheviks such as Leon Trotsky and links drawn between the Bolshevik Revolution and theories about international Jewish conspiracies such as those proposed in the Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion- a document forged by Tsarist intelligence.[21] This view was promoted by Winston Churchill in a 1920 article entitled “Zionism versus Bolshevism: A Struggle for the Soul of the Jewish People” In it Churchill praised Jewish people as the “most formidable and most remarkable race which has ever appeared in the world” and credited them with the creation of a “system of ethics” which was the basis of the modern Christian world. However, he also claimed Jewish people might be “in the actual process of producing another system of morals and philosophy, as malevolent as Christianity was benevolent, which if not arrested, would shatter irretrievably all that Christianity has rendered possible. It would almost seem as if the gospel of Christ and the gospel of Antichrist were destined to originate among the same people; and that this mystic and mysterious race had been chosen for the supreme manifestations, both of the divine and the diabolical.”[22] *Anti-Bolshevik poster, 1918 Even many of those who were less inclined to see a theological angle to the Bolshevik Revolution were still attracted to the idea that the Russian Revolution was part of a global Jewish conspiracy. A 1920 article in the London Times discussed a book by a Russian author- Professor S. Nilus- called “The Jewish Peril”, which was published in 1905 and incorporated the Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion. While casting doubt on the veracity of the Protocols and other assertions in the book, the Times’s correspondent could not help but see something “uncanny” in its predictions given that “15 years later, a government [was] established in Russia of which a high percentage of the leaders are Jews, whose modus operandi follows the principles quoted.”[23] With this ominous specter supposedly arising in the Jewish people, a different ideology was required to combat it. Thus, many settled on Zionism to counteract communist influence among Jewish people. As Churchill put it in his essay, “Zionism has already become a factor in the political convulsions of Russia, as a powerful competing influence in Bolshevik circles with the international communistic system… The struggle which is now beginning between the Zionist and Bolshevik Jews is little less than a struggle for the soul of the Jewish people.”[24] This helps demonstrate that a crucial aspect of Zionism and its relationship with the British was its leaders’ ideological identification with the west. Zionism not only represented a surrogate of “Western Civilization”, it also helped create the ideological justification for British colonization in West Asia. Both the British and Zionists were met with a similar dilemma: an indigenous population that did not want them there. For Zionists it was indigenous Palestinians who feared losing their land. For the British it was the inhabitants of its broader empire, but particularly those in the areas of the former-Ottoman Empire which it had just been granted by the League of Nations.* While the British already had a long history of studying how to rule subject peoples, these new subjects were former members of an empire which relied on local institutions for administration and had been expecting to be granted independence after the Arab Revolt.[25] Thus, Zionists served a special ideological function for he British in West Asia. Building on previous British orientalism, Zionists produced ways of understanding Britain’s Arab subjects in a sort of ideological parallel construction which helped to justify each other’s colonial projects. According to Edward Said, Zionists generally ignored the Arab but “when it was necessary to deal with him, they made him intelligible, they represented him to the West as something that could be understood and managed in specific ways.”[26] Both the British and Zionists believed in the inherent superiority of “Western Civilization” and viewed Zionism as an extension of that civilization into the orient. As Said put it, “Between Zionism and the West there was and still is a community of language and of ideology; so far as the Arab was concerned, he was not part of this community.”[27] To the British and Zionists, the Arabs were an undifferentiated, backwards mass without national loyalties- Arabs in Palestine were interchangeable with Arabs in Syria who were interchangeable with Arabs in Iraq, etc.[28] According to Zionists, the people of Palestine were composed of the hopelessly backwards fellah (peasant) who labored for the benefit of his greedy, deceitful effendi (large landlord). The Zionists claimed this was hardly a group which could compose a nation. As Chaim Weizmann wrote to Lord Balfour in 1918, “The present state of affairs would necessarily tend towards the creation of an Arab Palestine, if there were an Arab people in Palestine. It will not in fact produce that result because the fellah is at least four centuries behind the times, and the effendi (who, by the way, is the real gainer from the present system) is dishonest, uneducated, greedy, and as unpatriotic as he is inefficient.”[29] In contrast, Zionists portrayed themselves and the British as bearers of progress, liberal democracy, and “Western Civilization” which would transform Palestine into a national home for a marginalized people and solve the “Jewish Question”.[30] How could the objections of such indigenous inhabitants stand in the way of this benevolent project? When Zionists were not attempting to erase or delegitimize the indigenous presence in Palestine, they were arguing Zionism would be beneficial to Palestinians who would gain from the progress brought by “Western Civilization” and the economic stimulation from capital and immigrants entering the country. According to Zionists, particularly Labor Zionists who fancied themselves socialist, the only people in Palestine who could oppose the Zionist mission were effendis who feared losing their grip over the peasantry as anticipated economic prosperity would increase employment opportunities for rural Palestinians.[31] As one of the founders of the Labor Zionist party Ahdut Ha’avoda (“Unity of Labor”), Yitzhak Ben-Tzvi, put it, “[the peasant] does not suffer from Jewish immigration, but from the pressure of his effendi and from exploitation by the city dweller, who is of the same race and religion and mediates between him and the effendi… The peasant is also interested in the expansion of employment and industry in the country and the improvement of the workers’ lot, which of necessity results from Jewish settlement and immigration. Thus, the peasant is not opposed to immigration.”[32] Therefore, with Zionist and peasant interests aligned, the only explanation for anti-Zionist disturbances in Palestine was the lies and machinations of the pseudo-nationalist effendis or “outside agitators”, particularly communists. *Anti-Zionist demonstration at the Damascus Gate in Jerusalem, March 8, 1920 In coming to this conclusion, Zionists drew on existing colonial discourses which represented colonized people as irrational, submissive, and incapable of intelligent thought.[33] While Europeans thought this justified the subjugation of colonized people, they also feared it hid a latent danger. While the colonized were generally docile, their simple nature also made them gullible and easily manipulated by agitators exploiting them for their own interests. One US pastor put it rather succinctly in an interview after visiting Palestine in which he claimed, “But for the Arab agitators, the rank and file of the Jews and the natives would live in harmony and happiness. The Arab needs the push and pluck of the Jews. The Jew in turn needs the Arab. As soon as the agitators drop their tomfoolery no doubt these two forces will begin to co-operate and make Palestine a delightful land.”[34] To the British, an important source of this agitation was communist activists attempting to undermine British rule.[35] While this helped the Zionists in some ways given the communists’ anti-Zionism, it was a double-edged sword as many British officials failed to recognize the difference between communists and Zionists, particularly the avowedly socialist variety.[36] Zionists recognized it could threaten continued Jewish immigration to Palestine if British officials viewed all immigrants as potential Bolsheviks. For instance, in a speech to the Overseas Club in 1921 explorer Rosita Forbes reportedly claimed there had been 30,000 Jewish immigrants into Palestine in the previous year and 29,999 of them were Bolsheviks.[37] Zionists faced this dilemma by downplaying the numerical significance of Jewish communists in Palestine while maintaining the communist threat. In a letter responding to a letter by Lord Eustace Percy published in the London Times which warned of communist influence in Palestine, T. Radler-Feldman of the Mizrashi Organization in Jerusalem insisted it was unlikely there were a dozen communists in all of Palestine. On the other hand, “The organized attacks on the farmers in several Jewish colonies show clearly that this Arab movement has nothing to do with fighting against Bolshevism, but is, on the contrary, in the blind destroying of capitalist property, itself Bolshevism.”[38] In a reply, Lord Percy summarized an ideological synthesis that seemed to solve this problem when he wrote, “it is the influence exerted by these small groups upon the fears and prejudices of other members of their race who do not share their views that the chief danger of the present situation lies… Not only in Palestine, but in all parts of the world to-day, the hope of peace depends more upon active efforts to counteract such influences than upon the mere excommunication of a few extremists.”[39] While Percy was criticizing the Zionists, this line of reasoning was actually advantageous to Zionists. It allowed them to discount fears over Jewish immigration and use British resources to repress communists, particularly after they took a more hardline anti-Zionist position. A major point of contention under the mandate regarded Jewish immigration to Palestine. Given that at the beginning of the mandate Jews composed a miniscule fraction of the population of Palestine, large-scale Jewish immigration was necessary to achieve Zionist aspirations of a Jewish state.[40] However, consistent immigration was not always easy to secure given the hostility of indigenous Palestinians and British fears of Bolshevik Jews infiltrating the country.[41] The British administration implemented a quota system, which, as stipulated in the Mandate charter, was to be determined by Palestine’s economic “absorptive capacity”.[42] The charter also specified British immigration policy must prioritize Jewish immigration and be directed towards establishing a Jewish national home, which could be hampered by too much competing non-Jewish immigration.[43] Thus, the British established a permit system to govern immigration to Palestine, which it largely left under the control of the Zionist movement. Indeed, while permits formally came from the British, who received a permit was determined by Zionist leaders.[44] However, the British still needed to ensure “undesirable elements” would not be able to enter the country, so they established a strict documentary system of passports and visas, which allowed officials to track potential undesirables.[45] While officials took many factors into consideration, such as wealth, occupation, and physical ability, an important concern was to screen for individuals who may attempt to undermine British rule in Palestine.[46] One of the first groups of immigrants to be targeted for this were Eastern European, particularly Russian, Jews, who the British associated with the Bolsheviks. The administration formed the Inter-departmental Committee on Immigration from Russia specifically to establish rules meant to prevent the entry of potentially subversive Jewish immigrants from Russia.[47] Further, the establishment of frontier checkpoints to enforce this system had the added benefit of limiting the fluidity of travel in and out of Palestine thus restricting the mobility of subversive populations. This was particularly targeted towards those travelling to the Soviet Union, who the British feared may be cooperating with the Bolsheviks and the Communist International (Comintern).[48] *British security forces searching Palestinian civilians, April 1920. Obviously, this vigilance did not stop at the border. The British administration sought to crush communist activity wherever it appeared and many of the repressive institutions established under the British mandate were created, at least in part, as a response to the communist threat.[49] Following allied occupation of Palestine at the end of 1917, the British established military rule and created a police force consisting mostly of locally recruited men. The demographic composition of this police force was meant to be roughly proportional to each religious group’s representation in the general population- 70% Muslim, 20% Christian, and 10% Jewish.[50] In the first few months of 1920, several anti-British demonstrations and violent attacks in Jerusalem during the religious celebration of al-Nabi Musa (Prophet Moses), which killed five Jews, led to the end of military rule in Palestine.[51] The military, which Zionists accused of mishandling the riots and having pro-Arab, anti-Jewish sentiments, was replaced by a civilian administration headed by a high commissioner, Sir Herbert Samuel, a staunch Zionist.[52] The new civilian administration sought to reform the police to make them more effective and more friendly to Zionism. The establishment of a Zionist friendly police force drew upon British police practices in other colonies and was facilitated by a mutual British-Zionist interest in anti-communism. *Al-Nabi Musa procession, April 4, 1920. The first important communist party in Palestine was the Mifleget Poalim Sozialistit (Socialist Workers Party), which was the result of a split between left and right factions in the broader Labor Zionist party, Poalei Zion (Workers of Zion). The much larger right-wing joined with other independent groups to form the party Ahdut ha-Avodah (Unity of Labor).[53] While the MPS still considered itself a Zionist party, it called for dialogue with Palestinian workers and denounced Ahdut ha-Avodah’s willingness to collaborate with the Zionist bourgeoisie.[54] The MPS had already appeared on the British administration’s radar in 1920 after the party’s celebration for the anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution when police arrested party members and closed its clubs.[55] Communist activity became a center of attention after the Jaffa riots in 1921, which revolved around a May Day celebration. The night before May 1, the MPS sent out boys to distribute pamphlets calling for revolution against British imperialism and the creation of a Soviet Union of Palestine.[56] The next day the party organized a May Day parade in Tel Aviv. When the communist demonstration ran into the official Labor Zionist May Day demonstration organized by Ahdut ha-Avodah, it led to a violent skirmish between the two demonstrations. The police soon began driving the communist demonstration out of Tel Aviv towards Jaffa. On their way, the communist demonstration ran into Palestinians who were not any more friendly towards a Zionist Soviet Union of Palestine.[57] Next, Palestinians would unleash a wave of mass violence against Jewish residents of Jaffa, killing men, women, and children. When news of the attacks reached a military camp where soldiers who served in the British Jewish Battalion during WWI were billeted, they quickly prepared to retaliate, and the next morning released their own wave of violence against Palestinians in Jaffa.[58] By May 3, the British had declared martial law. All told, 47 Jews and 48 Palestinians were killed, while 146 Jews and 73 Palestinians were injured.[59] The British administration quickly capitalized on the violence as an opportunity to scapegoat and target communists. On May 4 the London Times ran an article headlined “The Jaffa Riots: Communist Jews Start New Trouble”[60], and, on the same day, the New York Times reported, “Jews emigrating from Russia to Palestine appear to have included a number of Bolshevist agents, who have succeeded in stirring up serious trouble, leading to bloody fights involving emigres, natives and British soldiers charged with maintaining order.”[61] Even the government’s commission of inquiry blamed the MPS for antagonizing Palestinians, although it did discount their actual numbers and influence.[62] While the riots were still ongoing, British high commissioner, Herbert Samuel, issued an order to arrest and deport the communist leaders and track their underground activities.[63] The riots also provided a fresh impetus for the police reform the civilian administration had been planning. Instead of making any significant changes to the existing police force, the administration chose to supplement it with two gendarmeries- one Palestinian and one British. The Palestinian gendarmerie was to be composed of both Palestinians and Jews and commanded by British officers.[64] A major responsibility for this unit was to assist in the defense of frontier Jewish settlements, which had been targeted by Palestinians during the Jaffa riots.[65] For further protection, the mandate administration provided each Jewish colony with a sealed armory for its defense.[66] The British gendarmerie was formed under the leadership of General Hugh Tudor, former commander of the notorious Black and Tans- a British paramilitary outfit which had served in Northern Ireland in the early 1920s.[67] Most of the recruits for the British gendarmerie in Palestine were former members of the Black and Tans or the Royal Irish Constabulary who needed work after Ireland became a dominion in 1921.[68] The methods employed by the Black and Tans were infamous for their brutality, and, even after the gendarmeries were disbanded in 1926, many of its members were simply absorbed by the regular police.[69] *Major General Hugh Tudor Within the Palestine Police Force, the unit responsible for supplying information and intelligence was the Criminal Investigation Department (CID).[70] In 1921 the British established a section within the CID devoted to targeting communists located in Tel Aviv.[71] This section was heavily dependent on the cooperation with Zionists who knew the political complexities of the Yishuv and spoke Yiddish.[72] This anti-communist section mainly focused on surveilling communist activists, gathering intelligence, and disrupting party activities. For instance, police routinely broke up communist demonstrations (particularly May Day), raided party offices, and confiscated party literature.[73] Of particular importance was tracking party contacts with communist organizations outside of Palestine, which normally entailed the seizure of party documents or trailing party messengers or representatives during foreign travels.[74] After a couple of years of this harassment and surveillance, most of the party’s top leaders had been arrested or were under surveillance, and, by the end of 1924, police began censoring party members’ mail.[75] One of the British administration’s favorite methods for dealing with political opponents was deportation. Communists were frequently targeted for deportation, but this presented its own issues as many Eastern European countries where these immigrants hailed from were unwilling to repatriate known communist activists.[76] This left the communists in a sort of limbo of remaining in Palestine under strict surveillance or wallowing in prison, where conditions were atrocious and floggings were frequent.[77] Zionist cooperation in these police units and carceral systems was key in smoothing the way for further British-Zionist cooperation in security, intelligence and military activities. This coincided with the communists’ increasing ostracism within the Yishuv and its labor movement. Already in 1922 David Ben-Gurion had convinced the Trade Unions Executive Council to expel MPS members.[78] The MPS had become increasingly unwelcome within the Histadrut (Jewish General Federation of Labor)* due to its criticisms of the Histadrut’s nationalism and its insistence on reaching out to Palestinian workers.[79] This increased pressure pushed the communists underground where they formed the Fraktzia (Workers’ Faction), which aimed to enter the trade unions affiliated with Histadrut and open them to Palestinian membership.[80] This enmity only increased as the MPS disintegrated, and remnants of the party formed the Palestine Communist Party (PCP) in 1923.[81] This new party took a more openly anti-Zionist position and intensified efforts at organizing Palestinian workers- policies which were more in line with the Comintern.[82] These efforts paid off as the party was accepted to the Communist International as the official representative in Palestine.[83] While this qualified the party for outside assistance, these new stances led Histadrut leaders to tighten their vice grip on the party within the trade union movement. In 1924 the Histadrut launched a systematic purge of communists from the trade unions and affiliated institutions.[84] Additionally, Labor Zionist leaders targeted communists’ livelihoods by pressuring employers to fire communist employees, having them removed from workers’ hostels, and refusing them access to the trade union’s sick fund.[85] While Zionist labor leaders claimed they opposed the deportation of Jewish communists and their harsh prison conditions, this anti-communist campaign had the effect of outing those expelled from or denied admission to the trade unions as active communists.[86] In this way, Labor Zionists got to have their cake and eat it too. They could condemn the brutality of the British authorities while facilitating their work. By the end of 1924, the communist movement in Palestine had been decimated, with most of its leaders in jail or under surveillance. In the following years, it would further pivot to organizing efforts among Palestinians and played a more active role in supporting Palestinian nationalism. While the party would remain active throughout the mandate period, it never truly had much influence within Palestine. Its main significance was how red panic induce fears in the British Empire created the ideological buttressing which justified British support for Zionism and shaped its governance over Palestine. Zionists were able to capitalize on this not only to garner support for a Jewish national home but also to ease the way for British-Zionist security, intelligence, and military cooperation. This helped to strengthen the ties between the British and the Zionists and in many ways made the British dependent on Zionist participation in maintaining order in Palestine. It also enhanced the Yishuv’s police and military capabilities, which would be important in future years, particularly the 1948 war and its resulting expulsion of Palestinians. Ultimately, while communism never held much sway in Palestine, its specter influenced decisions that would have long-lasting effects on the future of Palestine. Work Cited [1] Zachary Lockman, Comrades and Enemies: Arab and Jewish Workers in Palestine, 1906-1948. (Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2010), 38-45. [2] Walid Sharif, “Soviet Marxism and Zionism,” Journal of Palestine Studies 6, no. 3 (Spring 1977): 81-83, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2535581 [3] Karl Marx, “On the Jewish Question”, Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher (February 1844), https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/jewish-question/ [4] Walid Sharif, “Soviet Marxism and Zionism,” Journal of Palestine Studies 6, no. 3 (Spring 1977): 82-83, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2535581 [5] Ibid, 83 [6] Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under the British Mandate, trans. Haim Watzman (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 1999), 38 [7] “The Jews and the Young Turks,” The Times (London), August 9, 1911, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS151584009/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=a36e03cd. “Jews and the Situation in Albania,” The Times (London), July 11, 1911, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS84999403/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=b2b0f999. [8] “Jews and the Situation in Albania,” The Times (London), August 9, 1911, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS52624649/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=eeebe3d9. [9] Oren Kessler, “Mandate 100: ‘A dangerous people to quarrel with’: Lloyd George’s Secret Testimony to the Peel Commission Revealed,” Fathom (July 2020), https://fathomjournal.org/mandate100-a-dangerous-people-to-quarrel-with-lloyd-georges-secret-testimony-to-the-peel-commission-revealed/#_edn15. [10] “Central Powers and Zionist Aspirations,” The Times (London), November 30, 1917, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS117770622/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=a18002a6. Jehuda Reinharz, “The Balfour Declaration and Its Maker: A Reassessment,” Journal of Modern History 64 (September 1992): 485-486. [11] “The Jews and Palestine,” The Times (London), October 26, 1917, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS117901658/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=3b31c162. [12] Ibid. [13] “German Gold for Lenin,” The Times (London), February 9, 1918, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS102173257/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=0f4c1ff7. [14] “The German Hand In Russia,” The Times (London), February 9, 1918, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS102173257/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=0f4c1ff7. [15] Steven Wagner, Statecraft By Stealth: Secret Intelligence and British Rule in Palestine (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019), 26, https://books.google.com/books/about/Statecraft_by_Stealth.html?id=FKhzDwAAQBAJ. [16] Oren Kessler, “Mandate 100: ‘A dangerous people to quarrel with’: Lloyd George’s Secret Testimony to the Peel Commission Revealed,” Fathom (July 2020), https://fathomjournal.org/mandate100-a-dangerous-people-to-quarrel-with-lloyd-georges-secret-testimony-to-the-peel-commission-revealed/#_edn15. [17] Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under the British Mandate, trans. Haim Watzman (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 1999), 41-42 [18] “The Future of the Jews,” The Times (London), letter, May 28, 1917, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS84084924/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=1591a199 [19] Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under the British Mandate, trans. Haim Watzman (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 1999), 42-43 [20] Alyson Pendlebury, “The Politics of the ‘Last Days’: Bolshevism, Zionism and ‘the Jews’,” Jewish Culture and History 2, no. 2 (Winter 1999): 96-115, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1462169X.1999.10511933. [21] Ibid, 110 [22] Winston Churchill, “Zionism Versus Bolshevism: A Struggle for the Sole of the Jewish People,” Illustrated Sunday Herald, February 8, 1920. [23] “The Jewish Peril,” The Times (London), June 2, 1920, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS101387970/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=bf3907c9 [24] Winston Churchill, “Zionism Versus Bolshevism: A Struggle for the Sole of the Jewish People,” Illustrated Sunday Herald, February 8, 1920 [25] Elizabeth F. Thompson, How the West Stole Democracy From the Arabs: The Syrian Arab Congress of 1920 and the Destruction of Its Historic Liberal-Islamic Alliance, (New York, NY: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2020), 14. [26] Edward Said, The Question of Palestine, (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1979), 25. *In 1919, the newly formed League Nations decided on how to administer territories which had been possessions of WWI’s losers. The League established a series of “mandates” for these territories which assigned European powers to administer them. These were meant to be temporary arrangements where people deemed not yet ready for self-rule would be placed under the tutelage of Europeans until they were. [27] Ibid [28] Zachary Lockman, Comrades and Enemies: Arab and Jewish Workers in Palestine, 1906-1948. (Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2010), 29-36. [29] Doreen Ingrams, Palestine Papers, 1917-1922: Seeds of Conflict, (London: Cox & Wyman Ltd., 1972), 31-32. [30] Edward Said, The Question of Palestine, (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1979), 28-29 [31] Zachary Lockman, Comrades and Enemies: Arab and Jewish Workers in Palestine, 1906-1948. (Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2010), 59-63. Johan Franzen, “Communism Versus Zionism: The Comintern, Yishuvism, and the Palestine Communist Party,” 36, no. 2 (Winter 2007): 10-11, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jps.2007.36.2.6 [32] Ibid, 60. [33] Edward Said, Orientalism, (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1979), 206-208, 227-231. Zachary Lockman, Comrades and Enemies: Arab and Jewish Workers in Palestine, 1906-1948. (Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2010), 64. [34] “Arab Agitators Only Troublesome Element In Palestine Pastor Avers,” The Sentinel, October 21, 1921, https://www.nli.org.il/en/newspapers/cgs/1921/10/21/01/article/115/?srpos=2&e=-------en-20--1--img-txIN%7ctxTI-agitators+palestine-------------1. [35] “Palestine From Day to Day: Bolshevik Intrigue in Palestine,” The Palestine Bulletin, February 26, 1925, https://www.nli.org.il/en/newspapers/plb/1925/02/26/01/?srpos=18&e=-------en-20--1-byDA-img-txIN%7ctxTI-Communist+----------Jerusalem---1. “The East Offers Favourable Ground for Bolshevism,” The Palestine Bulletin, February 24, 1926, https://www.nli.org.il/en/newspapers/plb/1926/02/24/01/article/7/?srpos=42&e=-------en-20--41-byDA-img-txIN%7ctxTI-Communist+Palestine----------Jerusalem---1. [36] Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under the British Mandate, trans. Haim Watzman (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 1999), 141. [37] S. Landman, “The Jews In Palestine,” The Times (London), May 27, 1921, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS101650619/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=72173bef [38] T. Radler-Feldman, “Jews In Palestine: A Plea for the Zionist Commission,” The Times (London), July 16,1921, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS101388528/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=e1b6c211. [39] Eustace Percy, “Jews In Palestine,” The Times (London), July 23, 1921, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS152768759/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=1c4c6657. [40] Rashid Khalidi, The Iron Cage: The Story of the Palestinian Struggle For Statehood, (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2006), 11-12. [41] “No Bolshevists For Palestine: Limit and Control of Immigration,” The Times (London), June 4, 1921, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS169283780/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=045c74bb Philip Graves, “Some Truths About Palestine: An Independent Inquiry: Placating The Rival Races,” The Times (London), April 4, 1922, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS117904004/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=12a87385 [42] “British Policy in Palestine”, The Times (London), January 15,1923, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS185013295/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=e80abd27 [43] H. Sidebotham, “The Jews In Palestine,” The Times (London), November 22, 1921, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS101388662/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=10826d67 Lauren Banko, ”Keeping Out the ‘Undesirable Elements’: The Treatment of Communists, Transients, Criminals, and the Ill in Mandate Palestine,” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, (February 2019): 5, https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2019.1576832. [44] Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under the British Mandate, trans. Haim Watzman (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 1999), 226-229 [45] Lauren Banko, ”Keeping Out the ‘Undesirable Elements’: The Treatment of Communists, Transients, Criminals, and the Ill in Mandate Palestine,” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, (February 2019): 5, https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2019.1576832. [46] Eli Tzur, ”The Silent Pact: Anti-Communist Co-operation between the Jewish Leadership and the British Administration in Palestine,” Middle Eastern Studies 35, no. 2 (April 1999): 107, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4284006 . [47] Lauren Banko, ”Keeping Out the ‘Undesirable Elements’: The Treatment of Communists, Transients, Criminals, and the Ill in Mandate Palestine,” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, (February 2019): 8, https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2019.1576832. [48] Ibid [49] Steven Wagner, Statecraft By Stealth: Secret Intelligence and British Rule in Palestine (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019), 54-55, https://books.google.com/books/about/Statecraft_by_Stealth.html?id=FKhzDwAAQBAJ. [50] Eli Tzur, ”The Silent Pact: Anti-Communist Co-operation between the Jewish Leadership and the British Administration in Palestine,” Middle Eastern Studies 35, no. 2 (April 1999): 112, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4284006 . [51] John Knight, “Securing Zion?: Policing in British Palestine,” European Review of History 18, no. 4, (August 2011): 525, doi:10.1080/13507486.2011.590283. [52] Ibid [53] Musa Budeiri, The Palestine Communist Party, 1919-1948: Arab and Jew in the Struggle for Internationalism, (Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 1979), 5 [54]. Zachary Lockman, Comrades and Enemies: Arab and Jewish Workers in Palestine, 1906-1948. (Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2010), 66. [55] Eli Tzur, ”The Silent Pact: Anti-Communist Co-operation between the Jewish Leadership and the British Administration in Palestine,” Middle Eastern Studies 35, no. 2 (April 1999): 107, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4284006 . [56] Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under the British Mandate, trans. Haim Watzman (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 1999), 176. [57] Steven Wagner, Statecraft By Stealth: Secret Intelligence and British Rule in Palestine (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019), 54, https://books.google.com/books/about/Statecraft_by_Stealth.html?id=FKhzDwAAQBAJ. [58] Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under the British Mandate, trans. Haim Watzman (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 1999), 181. [59] Ibid, 183. [60] “The Jaffa Riots: Communist Jews Start New Trouble,” The Times (London), May 4, 1921, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS152375460/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=3fc00f1b [61] Edwin L. James, “Scores Are Killed In Palestine Riots: Bolshevist Agents Among Immigrants Provoke Serious Encounters With Troops: Jewish Shops Are Rifled,” New York Times, May 4, 1921, https://www.proquest.com/docview/98323451/36A6040F439240EAPQ/12?accountid=7286 [62] “The Jaffa Riots,” The Times (London), November 8, 1921, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS185536872/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=ee9a46d8 [63] Eli Tzur, ”The Silent Pact: Anti-Communist Co-operation between the Jewish Leadership and the British Administration in Palestine,” Middle Eastern Studies 35, no. 2 (April 1999): 108, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4284006 . [64] John Knight, “Securing Zion?: Policing in British Palestine,” European Review of History 18, no. 4, (August 2011): 526, doi:10.1080/13507486.2011.590283. [65] Ibid [66] Ibid [67] Ibid, 526-527 “Air Rank for G.O.C. Palestine,” The Times (London), January 24, 1923, https://link-gale-com.brooklyn.ezproxy.cuny.edu/apps/doc/CS169153592/TTDA?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=bookmark-TTDA&xid=0da63b12. [68] Matthew Hughes, “A British ‘Foreign Legion’?: The British Police in Mandate Palestine,” Middle Eastern Studies 49, no. 5 (2013): 697, : http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2013.811656. John Knight, “Securing Zion?: Policing in British Palestine,” European Review of History 18, no. 4, (August 2011): 527, doi:10.1080/13507486.2011.590283. [69] Ibid Eli Tzur, ”The Silent Pact: Anti-Communist Co-operation between the Jewish Leadership and the British Administration in Palestine,” Middle Eastern Studies 35, no. 2 (April 1999): 115, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4284006 . [70] Eldad Harouvi, Palestine Investigated: The Criminal Investigation Department of the Palestine Police Force, (Sussex: Sussex Academic Press, 2016). [71] Eli Tzur, ”The Silent Pact: Anti-Communist Co-operation between the Jewish Leadership and the British Administration in Palestine,” Middle Eastern Studies 35, no. 2 (April 1999): 115, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4284006 . Steven Wagner, Statecraft By Stealth: Secret Intelligence and British Rule in Palestine (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019), 54, https://books.google.com/books/about/Statecraft_by_Stealth.html?id=FKhzDwAAQBAJ. [72] Ibid [73] “Arrests Communists In Jerusalem Max Day Celebration,” Reform Advocate, May 12, 1923, https://www.nli.org.il/en/newspapers/refadv/1923/05/12/01/article/43/?srpos=20&e=------192-en-20--1--img-txIN%7ctxTI-Communists+palestine+-------------1. “Palestine Police Stop Soviet Celebration,” Sentinel, December 1, 1922, https://www.nli.org.il/en/newspapers/cgs/1922/12/01/01/article/150/?srpos=53&e=------192-en-20--41--img-txIN%7ctxTI-Communists+palestine+-------------1. “Many Injured in May Day Riots: Arrest Communists in Jerusalem,” Sentinel, May 11, 1923, https://www.nli.org.il/en/newspapers/cgs/1923/05/11/01/article/7/?srpos=59&e=------192-en-20--41--img-txIN%7ctxTI-Communists+palestine+-------------1. “Communists To Acre Jail,” Palestine Bulletin, May 5, 1925, https://www.nli.org.il/en/newspapers/plb/1925/05/05/01/?srpos=38&e=------192-en-20-plb-21--img-txIN%7ctxTI-Communists+palestine+----1925---------1. “Trial of Communists,” Palestine Bulletin, May 12, 1925, https://www.nli.org.il/en/newspapers/plb/1925/05/12/01/article/14/?srpos=2&e=------192-en-20-plb-1--img-txIN%7ctxTI-Communists+----1925---------1. “No Compensation For Jaffa Communists,” Palestine Bulletin, May 12, 1925, https://www.nli.org.il/en/newspapers/plb/1925/05/12/01/article/5/?e=------192-en-20-plb-1--img-txIN%7ctxTI-Communists+----1925---------1. [74] Eldad Harouvi, Palestine Investigated: The Criminal Investigation Department of the Palestine Police Force, (Sussex: Sussex Academic Press, 2016), 19. Steven Wagner, Statecraft By Stealth: Secret Intelligence and British Rule in Palestine (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019), 57-58, https://books.google.com/books/about/Statecraft_by_Stealth.html?id=FKhzDwAAQBAJ. [75] Ibid, 18. [76] Lauren Banko, ”Keeping Out the ‘Undesirable Elements’: The Treatment of Communists, Transients, Criminals, and the Ill in Mandate Palestine,” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, (February 2019): 6-11, https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2019.1576832. Eli Tzur, ”The Silent Pact: Anti-Communist Co-operation between the Jewish Leadership and the British Administration in Palestine,” Middle Eastern Studies 35, no. 2 (April 1999): 112-114, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4284006 . [77] Ibid, 115-119. Matthew Hughes, “A British ‘Foreign Legion’?: The British Police in Mandate Palestine,” Middle Eastern Studies 49, no. 5 (2013): 704-705, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2013.811656. [78] Ibid, 122-123. [79] Zachary Lockman, Comrades and Enemies: Arab and Jewish Workers in Palestine, 1906-1948. (Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2010), 130-133. [80] Musa Budeiri, The Palestine Communist Party, 1919-1948: Arab and Jew in the Struggle for Internationalism, (Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 1979), 6-7. [81] Joel Beinen, “The Palestine Communist Party, 1919-1948,” MERIP Reports, no. 55, (March 1977): 6, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3010830. [82] Ibid, 6-8. [83] Ibid, 6. *The Histadrut was a confederation of trade unions within the Yishuv in Palestine. The Histadrut was more than a trade union and established its own economic sector, which would dominate the Yishuv’s economy for years, and provided other necessary social services [84] Zachary Lockman, Comrades and Enemies: Arab and Jewish Workers in Palestine, 1906-1948. (Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2010), 130-133. William M. Feigenbaum, “How Communists Were Checkmated In Cloakmakers’ Union,” Forward, December 26, 1926, https://www.nli.org.il/en/newspapers/frw/1926/12/26/01/article/57/?srpos=28&e=-------en-20--21--img-txIN%7ctxTI-Federation+of+Jewish+labor+communists-------------1. [85] Eli Tzur, ”The Silent Pact: Anti-Communist Co-operation between the Jewish Leadership and the British Administration in Palestine,” Middle Eastern Studies 35, no. 2 (April 1999): 123-124, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4284006 . [86] Ibid, 124. AuthorAlex Zambito was born and raised in Savannah, GA. He graduated from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 2017 with a degree in History and Sociology. He is currently seeking a Masters in History at Brooklyn College. His Interest include the history of Socialist experiments and proletarian struggles across the world. Archives December 2021

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed