|

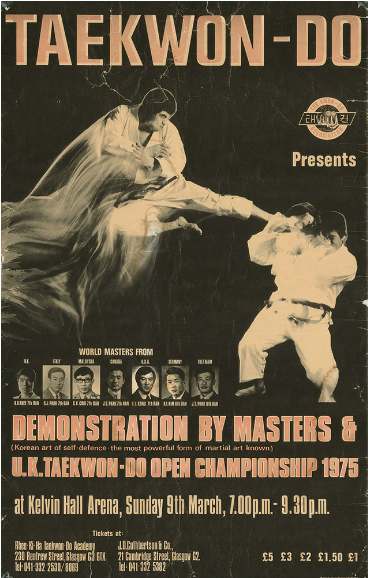

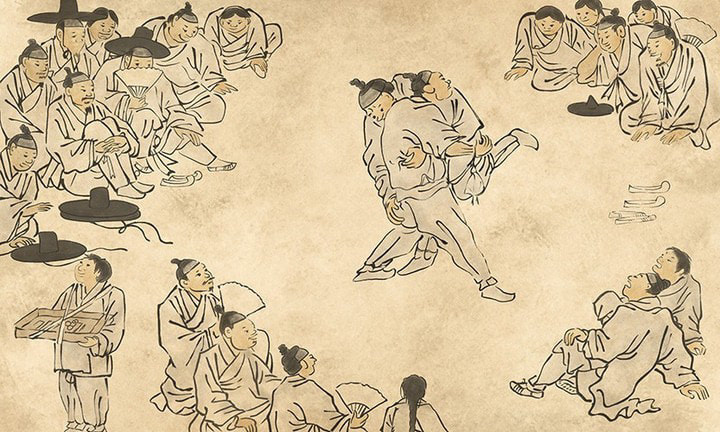

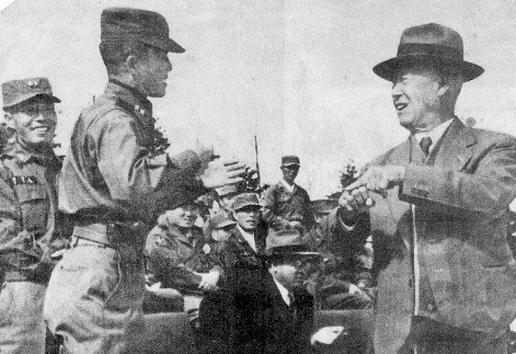

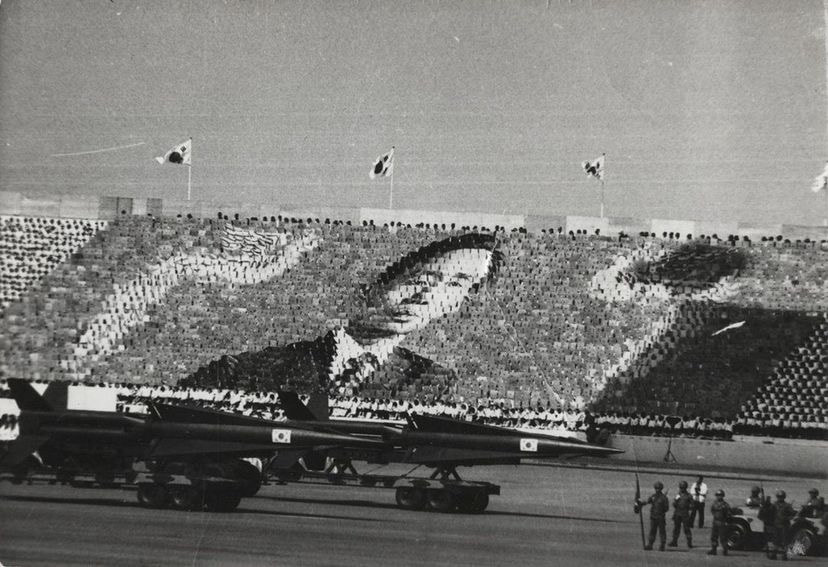

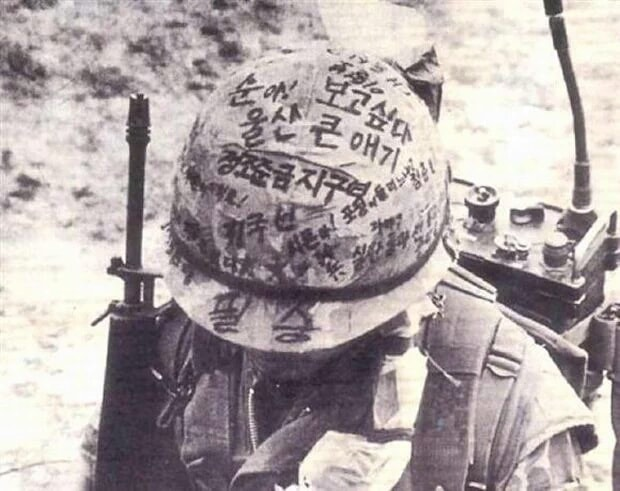

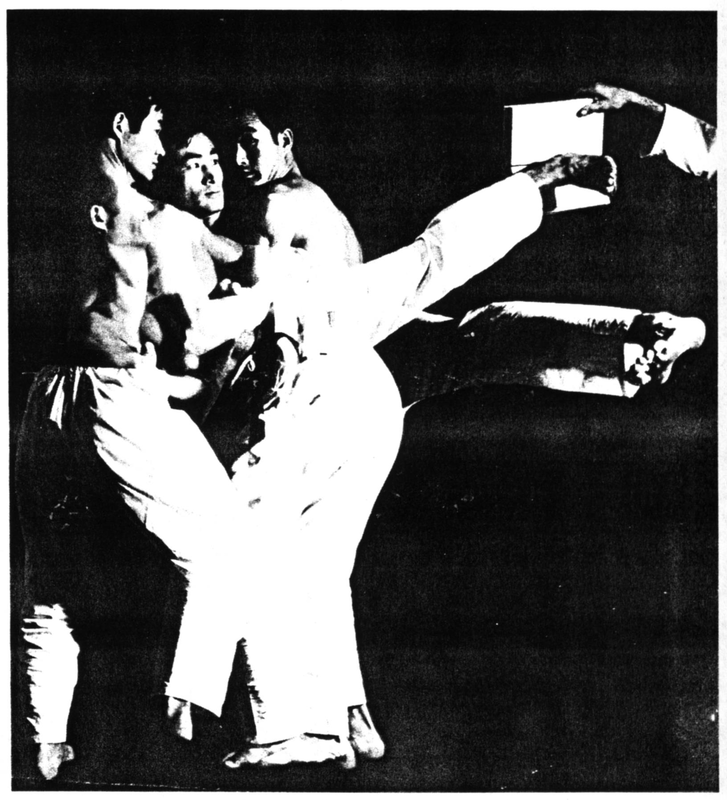

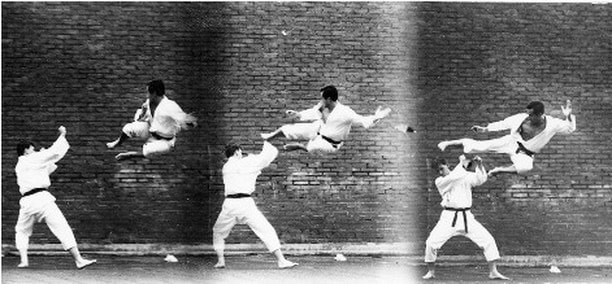

1938 would be the year that would forever change Choi Hong Hi’s life. That was the year Choi gambled away all the money his mother had saved for his schooling. In a fit of panic, Choi smashed an ink bottle over the winner’s head before running off to Japan. The man Choi had nearly killed was a local wrestler who swore that if Choi ever came back to the village, he would tear the five-foot-tall boy “limb from limb.” Four years later, Choi did come back to the village, but not before gathering a small crowd to watch him smash several roof tiles with such speed that the wrestler thought Choi was having a stroke. Choi would later call this martial art Taekwondo, and after rising to become a general in the South Korean army, named himself the founder. What started as a martial art in a tiny peninsula has 70 million practitioners in 203 nations today. It made the careers of famed action stars like Chuck Norris and Jean Claude Van Damme. A year after student-led protests forced the military dictatorship to accept democratic elections, Taekwondo was introduced to the Olympics, the second martial art to do so after Judo. What is less known is that the founder of Taekwondo’s largest federation was an agent for the South Korean secret police or that Choi Hong Hi’s son was once arrested for training North Korean commandos. Decades before Kpop or Squid Game were in the global lexicon, Taekwondo had clawed its way to become South Korea’s main cultural export. Raised by every major historical event that rocked the nation in the past century, including but not limited to: Japanese imperialism, the Korean War, military dictatorships, and even the emergence of anticommunist cults, it had come to be seen by many to symbolize South Korea’s resurrection from a nameless colony into the global powerhouse that Koreans still take deep pride in to this day. Taekwondo’s Foundation MythAccording to the World Taekwondo headquarters, also known as the Kukkiwon, Taekwondo is rooted in a 1500 year old martial art practiced by the Hwarang, warriors handpicked from the Silla dynasty’s nobility. The problem with that statement is that it's a total lie. The Hwarang were not only not an elite group of soldiers, they were actually young male aristocrats who danced and dressed in women’s clothing. Yi Jong Gu, who wrote many of the textbooks that fabricated this myth, confessed just as much in an interview; We didn’t have anything else to offer. In the early days of trying to introduce taekwondo abroad, if we said it was an ancient, traditional Korean martial art, we gained some bragging rights, plus this played well abroad. However, even if there are similarities, this just isn’t the truth. Alex Gillis’s extraordinary 1998 book “A Killing Art” digs deep into how Taekwando’s history was rewritten to fit the nationalist zeitgeist which characterized South Korea’s violent modernization. Gillis reveals that Taekwondo’s origins did not emerge in medieval Korea, but among the thousands of Koreans who migrated or were kidnapped to Japan. The lives of most Korean migrants in the Japanese Empire were characterized by grinding poverty and routine terror by roving fascist gangs. One of the most gruesome examples of anti-immigrant terror was when 2,000 Koreans were massacred in the aftermath of the Great Kanto earthquake. Naturally, the most hot blooded of these migrants learned Karate as a means of self defense. When the Japanese empire fell, they moved back to their homeland and set up karate gyms, which became a hotbed for street gangs and soldiers. These karate gyms, or kwans, would become the seeds for what would later be known as taekwondo. Choi Hong Hee, then a two star general, shows Rhee which two knuckles Nam used to smash thirteen roof tiles. Many of Taekwondo’s pioneers would be conscripted in their country’s civil war, where they would make their name. One of those men was Nam Tae Hi. In 1952, Nam enraged his commanding officer, who sent Nam’s unit on a suicide mission into no man’s land where they were soon caught up in a three day offensive by the People’s Liberation Army. To his horror, Nam realized that he’d run out of bullets before the Chinese ran out of bodies. The morning after the battle, Nam discovered that he was sleeping on the bodies of several dozen Chinese soldiers he had beaten to death with his bare hands. The battle would traumatize Nam for the rest of his life, but when Choi heard Nam’s story he recruited him to train other South Korean soldiers in what could still largely be considered Karate. Nam was so integral to ensuring Taekwondo’s emergence from obscurity, that it was he who broke the twelve roof tiles in front of South Korea’s first president and strongman, Rhee Syngman. Rhee was so pleased with the display that he gave Choi approval to build a martial arts gym inside a military base in Gangwon. Choi called this gym the Oh Do Kwan, “the Gym of My Way.” Funny enough, it was Rhee who gave Choi the idea for the name Taekwondo. When Choi told Rhee that Nam had used Karate to smash those tiles, the president bizarrely insisted that what Nam practiced wasn’t Karate, but instead was Taekkyon, a Korean street game. Before the war, Rhee was a noted independence activist and could not accept that what he saw was Japanese, so Choi rolled with it. Taekkyeon as one of Taekwondo’s origins was another lie that was propagated for decades. Taekwondo had taken over the military, but it would take another strongman for Taekwondo to be elevated to a national pastime. Park Chung Hee's KoreaLike Choi, Park Chung Hee came from humble beginnings. The son of disgraced aristocrats turned farmers, his mother tried to have Park aborted several times because she did not believe they could feed another mouth. These fears were not unfounded as malnourishment would stunt Park’s height at five foot four. Nevertheless, Park worked his way out of poverty and secured a comfortable job at a middle school, but he quickly grew bored with the banal life of a teacher. So in 1939, Park wrote an oath to the emperor in his own blood and mailed the letter to the Manchukuo Military Academy. 22 years later, Park stormed the presidential palace with a submachine gun, becoming South Korea’s first military dictator. To legitimize his rule, Park based his regime on Minjok, a particular form of ethno-nationalism. The core tenets of Minjok are the purity of the Korean identity (sunsuseong) and the obligation to regularly uplift Korea's cultural superiority (uwolseong). However, Park detested Korea’s past, especially the Joseon dynasty, whom he blamed for his family’s poverty and the nation’s capitulation to foreign powers. He once proclaimed that “we should set ablaze all our history that was more like a storehouse of evil.” He didn’t quite set Korea’s history ablaze, but he did rewrite it. While ethnonationalism precedes the Park regime, it was during this era that it enveloped South Korea with such brashness. It was a time “when Hangul was the world’s most beautiful writing system, when the mountains and rivers of Korea possessed the best vistas on the globe, and when Koreans were the smartest people on the planet.” Park Chung Hee’s transformation of South Korean society was premised on the “restoration” of what he called Korea’s pure culture; one defined by patriotism and military strength which had been erased during the period of colonial rule. Taekwondo’s ferocity as a killing art and fabricated history was the perfect tool to symbolize Park’s new Korea. Park elevated Taekwondo to a national sport, made it a mainstay in the country’s mass games, and eventually introduced it in every classroom, all in the service of “reinforcing the positive image of a strong martial leader.” In 1972, the Kukkiwon was established, the same year that a rigged plebiscite passed the Yushin constitution, which enacted a series of reforms that transformed the entire country into a giant bootcamp. Guitars and long hair were banned and police officers would carry around rulers to measure women’s skirts, all things popularly associated with South Korea’s dissident student population. For all it’s flair of restoring national purity, South Korean nationalism came from the same Japanese origin as Taekwondo. Park’s reforms were directly inspired by the Meiji restoration, when Japanese noblemen passed a series of westernizing reforms under the guise of “restoring the emperor.” Even the name Yushin, which means renewal, has the same Chinese characters as Meiji, and just like the architects of the Meiji restoration, Taekwondo’s leaders were not satisfied with taking over the country, they desired to expand beyond their provincial borders, even if it would take another war. The Vietnam War puts Taekwondo on the MapOnly one year after the Korean War “ended,” Western powers divided another Asian country into a Communist North and an Anti-Communist South. Park Chung Hee rapidly deployed 320,000 soldiers to Vietnam in order to access the billions of dollars in US aid that he would use to fund the meteoric economic growth that many call “the Miracle on the Han River.” The South Koreans had earned a reputation in Vietnam for ruthless efficiency. In 1966, a reporter from Time magazine wrote; To Westerners, the process sometimes seems as brutal as it is effective. Suspects [the Viet Cong] are encouraged to talk by a rifle fired just past the ear from behind while they are sitting on the edge of an open grave, or by a swift, cheekbone-shattering flick of a Korean’s bare hand. While we look now at such a statement with horror, the South Korean military took pride in their role as America’s “Hessians,” seeing Vietnam as a means to compensate for playing an auxiliary role in their own country’s civil war. Many veterans would eventually use the counterinsurgency tactics they tempered in Vietnam to suppress pro-democracy protests in their homeland. The Koreans used this notoriety to evangelize Taekwondo to the Americans and South Vietnamese, even sending instructors to the ARVN special forces training center. But, Taekwondo really exploded in 1967 when 250 Korean marines repelled nearly a thousand NVA and VC soldiers in Tra Binh. The “mythmaking marines,” as they were called, earned the respect of their American counterparts, due to their preference for using their hands over a bayonet. Curiously, one of the first Americans to earn a black belt was Robert Walson, who first discovered Taekwondo when he was a CIA agent in Vietnam. From the Bases to the SuburbsWhile public opinion was turning against the war in Vietnam, Choi was building a global empire through what he knew best, showmanship. His legendary Ace team were huge hits at military bases in West Germany, Singapore, and even Egypt. Aside from the usual ensemble of flying kicks and smashing bricks, brawling with spectators became a regular occurrence and the real money maker. Wherever the Ace team went, a new Taekwondo gym opened up, many suspiciously overnight. Though we can’t talk about Taekwondo’s reach abroad without Jhoon Rhee, “the father of American Taekwondo.” Rhee was close friends with a lot of future martial arts stars, including Chuck Norris, who had learned Taekwondo while he was an airman stationed in Osan. In 1965, Rhee convinced NBC to film his second national championship, but the suits at the network were so shocked by the violence that they only aired snippets. One thing that Taekwondo had going for it was it’s brutally powerful kicks. In South Korea, the White Claw, plain clothed police officers who sported motorcycle helmets, found these kicks useful in cracking the skulls of students, but in America they became popular in the national Karate circuit. As one American Karate champion explained, “The Japanese had poor kicks compared to the Koreans. We kicked to hurt.” All of this was possible thanks to the generosity of the KCIA, the South Korean secret police. The KCIA had created a global mafia that extorted millionaires, ran businesses, tortured dissidents, and was shrouded in so much secrecy that even the US government didn’t fully know what they were up to. Thanks to its international associations, status as a legal business, and steady crop of fighters, Taekwondo had become one of the KCIA’s biggest fronts. Many of Taekwondo’s founding fathers had connections to the KCIA. Nam Tae Hi was on the KCIA bankroll from 1965 to ‘72. Kim Un Yong, the founder of the World Taekwondo Federation, was a senior spy. Jhoon Rhee had deep connections to both the KCIA and the Unification church, a cult founded by Sun Myung Moon, a staunch anticommunist whose followers (popularly referred to as “moonies”) believe is the reincarnation of Jesus Christ. During Rhee’s 2nd Karate tournament, the same one aired on NBC, you could see the Korean Ambassador and Rev. Sun Myung Moon sitting in the front row. The KCIA’s secret dealings would be exposed in 1967 when West German authorities had discovered that Yu Isang, a prominent composer, had boarded a plane to South Korea without a passport or plane ticket. The KCIA had kidnapped Yun and over a hundred other Koreans, where they were tortured and forced to issue false confessions of spying for the North. The East Berlin Case, as it was later dubbed, sparked international outrage, but what was less known was that many of the agents involved in the kidnappings were Taekwondo instructors. One of Choi’s students, Kim Kwang Il, was later discovered to be one of the KCIA agents involved in the kidnappings. Another Taekwondo instructor involved in the East Berlin Case, Lee Gye Hoon, eventually rose to the position of deputy director of the KCIA. As much controversy as these incidents created, Taekwondo, like the South Korean economy, seemed to grow with no end in sight. In 1981, the new military dictator, Chun Do Hwan, sent KCIA agents Kim Un Yong and “Pistol Park” Kyong Chu on a secret mission to secure South Korea the seat to host the 1988 Olympics. Operation Thunderbird, as it was called, involved several Taekwondo instructors and an absurd amount of bribery but it worked. That September, the IOC selected Seoul as the host for the 1988 Summer Olympics, beating out the frontrunner, Nagoya, Japan. To add icing on the cake, Taekwondo would be for the first time introduced to the Olympics as a demonstration sport. 35 nations would compete in what was an obscure martial art only 30 years ago. As one article in the Korean Journal put it, Taekwondo had achieved what “Korea’s most skilled diplomats have been unable to accomplish, that is, bring the citizens of advanced western countries to an attitude of respect before the Korean flag.” Taekwondo’s Decline and Communist RestorationHowever, acceptance into the exclusive club of the Olympics would prove to be Taekwondo’s peak. The 1987 revolution led to the demotion of the military clique and in turn the rise of the chaebols, the country’s oligarchs. Taekwondo quickly proved to be ill fit for the new era. South Korea needed a new mascot, one that better suited the nation’s transition from a scrappy mercenary to a commercial powerhouse. That mascot would be found almost a decade later when H.O.T popped into the scene, kickstarting the Kpop phenomenon. Macho men breaking boards were replaced with “flower boy” idols, whose androdynous appearances ironically resembled the mythical “Hwarang warriors” more than Taekwondo’s most grizzled veterans. Even as this was taking place, Taekwondo’s foundations were already being eroded by its very own leaders. The Olympics had no place for the blood and broken bones that characterized early championships. In order to enter the Olympics, Taekwondo had to be civilized. The World Taekwondo Federation introduced safety pads, a refined (but still easily riggable) point system, and most notoriously no more punches to the head, turning Taekwondo into the white whitewashed sport that many detractors now derogatorily call “foot fencing.” Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to say that Korea has not preserved the original spirit of Taekwondo, it just wasn’t the one in the South. In 1979, Choi Hong Hi shocked the world when he defected to North Korea. Just like in the South, Choi built up Taekwondo’s prestige by integrating the martial art into the Korean People’s Army, which every North Korean male is required to serve in for eight years. As previously mentioned, Choi’s own son would later be arrested in West Germany for training North Korean commandos who had infiltrated the country. While it may seem surprising that a former South Korean general would defect to the communist North, many years prior, Choi had nearly died in a Japanese jail for attempting to defect to Kim Il Sung’s partisans in Manchuria. That experience gave Choi a deep seated hatred for the collaborators who rose up to lead the South Korean government, including Park Chung Hee, himself. Choi’s relationship with the junta had soured so badly, that even before he defected, the government had banned Choi’s federation from the country. Today in North Korea you can still see army commandos practicing “the original form of Taekwondo.” You might even see them practice the final form Choi Hong Hee ever designed, Juche. ConclusionThe history of Taekwondo brings up a greater question on what masculinity means to the left. Gillis’s book is regularly filled with stories of high ranking officers dancing drunk and KCIA agents punching politicians. Choi Hong Hi had even once joked that to do politics in Taekwondo, one had to be good at drinking, gambling, fighting, and have at least one mistress. It should not come as a surprise then that Taekwondo’s founders named their martial art inside of a geisha house. Martial arts always had a strong allure among alienated young men by offering a means to reclaim their lost agency and self-respect. Taekwondo, and the peninsula’s broader militarization, promised to overcome what many nationalists at the time called “the rape of Korea.” But what happens when that promise was achieved by reproducing the same relationship of colonial terror and humiliation. This desire to overcome Korean’s perceived inferiority complex caused Choi to develop a lifelong obsession to prove that his martial art was superior to its Japanese brother. During a show in Egypt, a soldier had privately shown Choi that he could smash a small oblong stone in half with a karate chop. Choi found the display so threatening that he ordered someone find a stone ten times as large and had one of his Ace team members smash the rock to pieces. However, it is vital that we remember that Taekwondo didn’t start in the backrooms of the KCIA or war crimes committed in Vietnam, but among immigrant communities in the center of the Great East Co-Prosperity Sphere. This legacy still survives to this day in the very organization that embodies all things reactionary in the martial art, the World Taekwondo Federation. The WTF takes a lot of pride in sending instructors to migrant enclaves and countries in the periphery, which has caused the martial art to develop a reputation as a leveler for poorer nations in the Olympics. In 2008, celebrations erupted all across Afghanistan when Rohullah Nikpai clinched his country's first Olympic medal after he defeated two time champion Juan Antonio Ramos. Rohullah had first applied for the Afghan national team at a refugee camp in Iran. Taekwondo is a story about a failed decolonization project. It is part of a greater history when the South Korean state tried to create a new Korean identity, one they felt the people could take pride in, but required leaving in place the oppressive forces that had stolen their agency in the first place. But more than anything else, Taekwondo is a story of survival. Bibliography

Author Jay is a Korean-American, who has lived in South Korea, Vietnam, and the Midwest and East Coast of the United States. While studying in Iowa, he became a student organizer for a statewide organization fighting for Free College for All and co-founded the local Students for Bernie chapter, which is now a chapter of the Young Democratic Socialists of America. Jay is also one of the hosts of Red Star Over Asia, a podcast which interviews organizers, academics, and journalists on politics in the Asian continent from a socialist perspective. Archives January 2022

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed