|

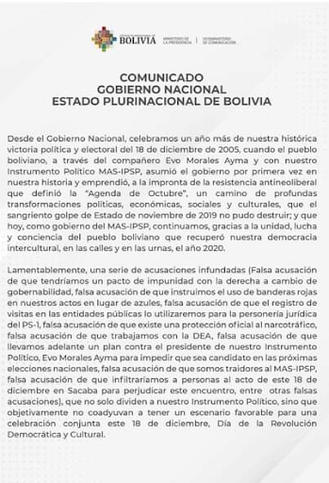

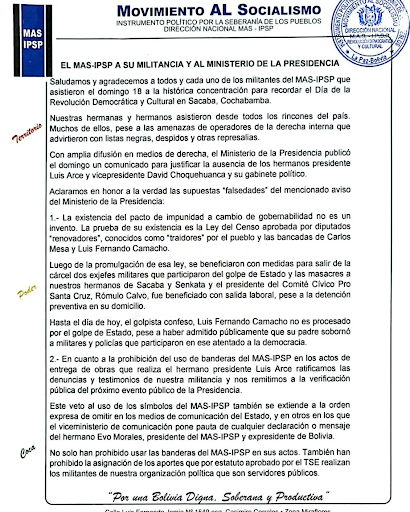

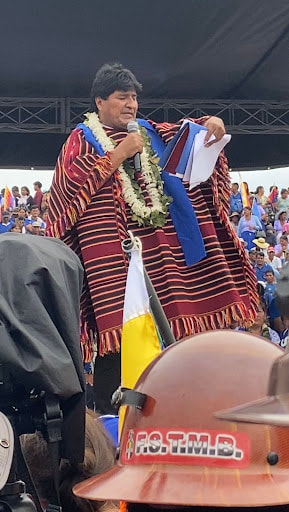

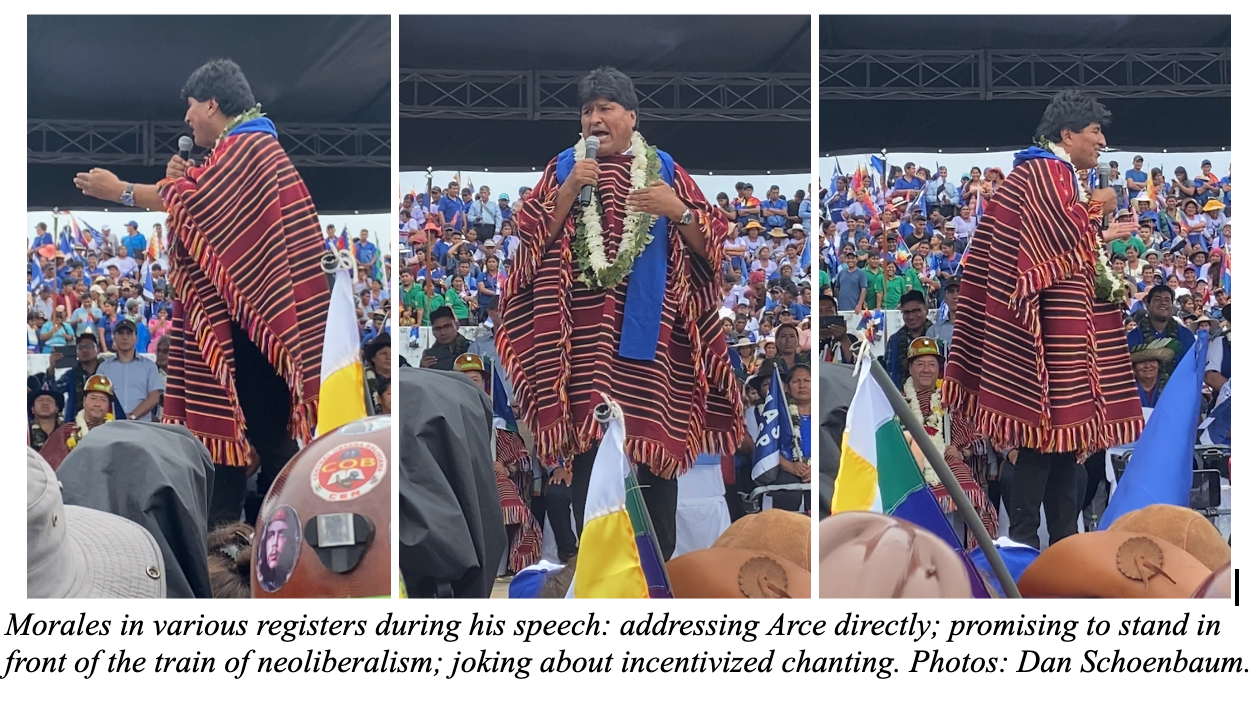

4/26/2023 “What unity are we talking about?”: MAS Celebrates its 28th Anniversary By: Dan SchoenbaumRead NowCrowd at Ivirgarzama, Bolivia, March 26, 2023. Photo: Dan Schoenbaum. Bolivia’s ruling political party held a rally this past March 26. To mark the 28th anniversary of their founding, the party known as MAS—officially MAS-IPSP (Movimiento al Socialismo – Instrumento Político por la Soberanía de los Pueblos; “Movement Toward Socialism–Political Instrument for the Sovereignty of the Peoples”)—called on their leaders, militants, and supporters from all over the country to converge in the town of Ivirgarzama. Normally around 70,000-strong, Ivirgarzama is the largest population center in the region known as the Trópico de Cochabamba. Among Bolivia’s departamentos, subnational divisions equivalent to states or provinces, Cochabamba is the only one that doesn’t border a different country. As tourist materials will tell you, Bolivia is at the heart of South America, and Cochabamba is at the heart of Bolivia. The Trópico refers to the section of Cochabamba covered by the Amazon rainforest. As the crow flies, the departamento’s capital, the city of Cochabamba, is separated from Ivirgarzama by less distance than is Manhattan from Scranton, but the bus ride between the two lasts seven hours. This is because midway to Cochabamba, the Andes start. Despite the town’s placement at the intersection of these extreme environments, the municipality’s mayor told local media in the days leading up to the rally that the event was expected to draw at least 35,000 attendees. That number represented the official capacity of the setting for the convention, Evo Morales Stadium. Having been there myself, I can confirm that the crowd filled the stadium’s seats and field at least to capacity. MAS supporters overflowed out every entrance and pooled around the stadium, where vendors sold everything from churros to chicken grilled on site; from plastic bags of drinking water to handfuls of the sacred coca leaf; from flags bearing the party colors of blue, white, and black to the rainbow patchwork banner of the Indigenous wiphala; from hand-stapled polemics to T-shirts packed with pictures of party leaders and masses; from lessons on tape for learning Bolivia’s most-spoken Indigenous languages, Quechua and Aymara, to umbrellas and ponchos for defense against the torrential rain that broke out the night before and continued on and off until the rally’s start around 11am. Clockwise from upper left: Evo Morales Stadium hours before the rally. A vendor outside the stadium offering MAS flags and accessories. The stadium stage during set-up. Vendors grilling under the stadium bleachers. Photos: Dan Schoenbaum. Since it’s the Amazon, rain is not unusual for Ivirgarzama. But the morning of the rally, a flood turned many of the main roads to the stadium into rivers. Cars, trucks, motorcycles, and vendors pushing carts on foot waded through the water. Thousands of people filtered from buses and packed hotels into one human stream running toward Evo Morales Stadium. When the president of MAS, Evo Morales himself, took the stage, he declared, “I understand the rain to be the greatest blessing, and in 2025, once again, we will win the elections!” For all the solidarity on display, this rally took place at a moment of serious political tension, both within Bolivia in general and within the structure of MAS itself. If the saying is true and war is how Americans learn geography, it makes sense that the 2019 US-backed coup d’état that removed MAS from power put Bolivia on the map for many outside the country. When, less than a year later, MAS returned to the presidency in a decisive electoral victory, the party and Bolivia as a whole became worldwide symbols of successful resistance against domestic antidemocratic reaction and international regime change. Now that a couple years have passed and the thrill of that triumph has receded, it is becoming harder and harder to ignore how much lasting damage the coup and its fallout did to Bolivia’s society, economy, and Movement Toward Socialism. The 2019 coup took place in the middle of a general election in which MAS’s presidential candidate was then-incumbent Evo Morales Ayma, seeking what would have been his fourth consecutive term as Bolivia’s president. After the counting of votes had been disrupted, Evo Morales had fled the country under threat of arrest or assassination by a military clique, and the obscure senator Jeanine Áñez of the Democratic Unity party had declared herself president in an infamous 11-minute parliamentary session, Áñez’s “transitional” government called new elections. However, the legislation to implement these snap elections barred anyone who had been elected in either of the previous two terms from running. This is where Bolivia’s current president, Luis Alberto Arce Catacora, came in. With Morales removed as an option, MAS party delegates elected Arce to be their new presidential candidate. Arce, however, was anything but a direct substitute for Morales. Evo, the single name by which Morales is known by supporters and detractors alike, is a born-and-raised campesino, a word often translated as “peasant” or “rural laborer” to capture its class connotation that literally signifies a person from the campo, the countryside. Neither of Morales’s parents knew their exact dates of birth, but according to the editor of his autobiography Mi Vida, when they married, his mother was around 30 years old while his father was between 16 and 17. Raised in an ayllu—a traditional community structure that predates the rule of the Incas—by a family who herded sheep and llamas, Morales made his name as a union organizer among the coca farmers of the Trópico de Cochabamba. He was present as a leader at every stage of MAS’s founding, including the March 26, 1995, date that so many came to commemorate in Ivirgarzama. Luis “Lucho” Arce grew up in the capital, La Paz, as the child of public school teachers. He worked almost two decades in Bolivia’s Central Bank and ran a Marxist reading circle on political economy. In Morales’s first cabinet, Arce headed the Ministry of Finance. He later assumed leadership of the new Ministry of Economy and Public Finance, which he ran up until the 2019 coup with the exception of a two-year medical sabbatical. Widely regarded as the brains behind the economic miracle that MAS’s tenure brought—more than quadrupling Bolivia’s GDP, cutting the country’s extreme poverty rate by more than half—Arce was held up in the 2020 post-coup re-do election as a symbol of the party’s technical proficiency, professionalism, and intellectualism. Compared to the coup regime, which wasted no time in dismantling public works projects, abandoning the population to uncontrolled covid spread, and cracking down on working-class dissent with bloody massacres, Arce’s appeal clearly won out, scoring him a first-round electoral victory with over 55% of the vote. But as a foil to Evo, in the eyes of much of the MAS base, Lucho almost inevitably stood in as well for depoliticization, compromise with rules written by coup-mongers, a sop to the middle class—in short, for moderation. That association only grew stronger as the difficulties of the post-coup, post-restoration status quo sank in. The extent to which Bolivia’s current economic stress can be attributed to lingering damage from the coup regime’s policies, mismanagement from the current government, or global crises outside any Bolivian’s control is a matter for debate, but there’s no arguing the fact that, as Morales told Arce at a departmental congress about a week before the Ivirgarzama rally, “We’re not so good economically.” Though Lucho takes every opportunity to tout the status of the inflation rate as one of the “lowest in the region”, GDP has returned to its pre-coup level, and it hasn’t gone much past that. That makes differences of outlook and policy harder to sweep under the rug. The political struggle that came to a head in the 2019 coup has by no means ended. Ex-president de facto Áñez was arrested in March 2021 on charges of terrorism, sedition, and conspiracy relating to the coup and was sentenced to ten years in prison in June 2022. But many of the coup’s other key players remained at large. The most conspicuous example was Luis Fernando Camacho Vaca, probably most well known outside Bolivia for storming the presidential palace in the first hours after Morales’s resignation, grabbing a quick photo op with a Bible laid on top of the Bolivian tricolor, and immediately exiting the building to bow his head in prayer before the pastor Luis Aruquipa while Aruquipa declared that, “the Bible is returning to the Palace of Government. Pachamama [the Andean deification of Mother Earth] will never return. Today Christ is returning here to the Palace of Government. Bolivia is for Christ.” Despite Camacho’s bragging on camera to his supporters that “it was my father who sealed a deal with the military [and] police” to secure Morales’s resignation, his case was complicated by the fact that in March 2021, Camacho was elected governor of his home departamento Santa Cruz. Bolivia’s easternmost departamento, Santa Cruz occupies the country’s lowland plains, where the population tends much more European in ancestry. Ranching and logging industries have built up a powerful regional oligarchy as well as the main cultural, political, economic, and demographic rival to the Andean center of gravity. That last field, demography, became the arena for the most significant political conflict in Bolivia in 2022. By October 2022, an arcane dispute over whether Bolivia’s next national census should take place in 2024 (following a delay established by presidential decree) or 2023 (as the opposition demanded) became the justification for Camacho and his allies to launch a paro, literally a “stoppage” but translated variously as “strike” by uncritical media and as “bosses’ lockout” by media that emphasized the dominant role played by the owning class in this action. Union workers reported threats by extremists to force them to close shop. At one point, frustrated laborers briefly seized over half a dozen shuttered factories in an industrial Santa Cruz suburb. In an ugly turning point for the campaign, a mob of Camacho’s supporters sacked and set fire to the departmental headquarters of CSUTCB, a campesino labor union. For this and other reasons, the regional stoppage mostly just seemed to hurt the region itself. Arce’s government was widely seen as taking a hands-off approach to the conflict, but after a little more than a month, the protest fizzled out, the paro was lifted November 26, and both sides seemed to accept the government’s victory and quietly walk away. Three weeks later, MAS started to make some noise. On the occasion of another anniversary rally, the December 18 celebration of the Día de la Revolución Democrática y Cultural (Day of the Democratic and Cultural Revolution), marking seventeen years Morales’s first election as president in 2005, Evo himself addressed a stadium of supporters in Sacaba. A heavily working-class suburb of the city of Cochabamba, Sacaba was the site of the coup government’s first public massacre, when, in the first days after Áñez’s self-appointment, police fired into a crowd of protesters, killing at least 11 and wounding around 100. That December 18 in 2022, the stadium was filled with calls for Morales to return to the presidency. Many in the crowd carried little white flags printed with Morales’s portrait, underlined by the title “COMANDANTE” and the years “2025–2030”. The audience waved their flags in enthusiasm for one speaker in particular: Flora Aguilar, executive of the Confederación Nacional de Mujeres Campesinas Indígenas Originarias. She mourned the recent legislative coup against Pedro Castillo and lawfare stitch-up against Cristina Kirchner, leftist leaders in Peru and Argentina, respectively. She also led the assembly in a chant of, “¡Evo de nuevo! ¡Evo de nuevo!” (“Evo again! Evo again!”) But the party leader who generated the most commotion was the one who was absent: President Arce. From left: Crowd at Sacaba Stadium, some holding a banner that reads, “EVO BOLIVIA TE NECESITA” (“Evo, Bolivia needs you”). Child waving a MAS flag with a portrait of Evo Morales and text that reads, “MAS-IPSP” and “EVO PRESIDENTE”. Attendees at the Sacaba rally, including a child in an aguayo. Photos: Dan Schoenbaum. Rather than show up to the rally, Arce’s office released a statement on the Día de la Revolución. In it, the Ministry of the Presidency celebrated “one more year since our historic political and electoral victory of December 18, 2005, when the Bolivian people, through comrade Evo Morales Ayma and with our Political Instrument MAS-IPSP, took up control of the government for the first time in our history”. But it also took the opportunity to condemn “a series of unfounded accusations”. These included the “false accusation that we work with the DEA”, the “false accusation that we order the use of red flags in our [public] acts in place of blue ones”, and the “false accusation that we have a pact of impunity with the Right in exchange for the ability to govern”. Two days later, the National Directorate of MAS released a statement of its own. Addressed from “MAS-IPSP to its militancy and to the Ministry of the Presidency”, the statement accused the Ministry of the Presidency of publishing its communication “in order to justify the absence of brothers President Luis Arce and Vice President David Choquehuanca and their political cabinet” at the recent rally. It also set out to “clarify, in honor of the truth, the supposed ‘falsities’ in said statement”. Respective cover pages of statements from the Ministry of the Presidency of Bolivia and from the National Directorate of MAS-IPSP. Photos, left to right: https://www.mintrabajo.gob.bo/. https://twitter.com/, @BOmereceMAS. In terms of the DEA, the Directorate pointed to the government’s January 2022 arrest of Maximiliano Dávila, former director of Bolivia’s FELCN (Fuerza Especial de Lucha Contra el Narcotráfico, “Special Force for the Fight Against Drug Trafficking”), when the Minister of Government announced at a press conference that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had reached out to the United States embassy to request information from a case against Dávila brought by the DEA. As for the colors of the flags, the Directorate referred to “complaints and testimonies from our militancy” that the flags and symbols of MAS had been banned from opening ceremonies for public works presided over by President Arce. Though the statement stopped short of claiming the suppression of blue (the color of MAS) and the promotion of red, it did take issue with Arce’s participation in a congress of the rival Socialist Party One (Partido Socialista Uno, or PS-1). Arce had been a member of PS-1 before joining Morales’s cabinet, and at that May Day congress in 2021, he certainly was decked out in the red of his former party. Luis Arce tweet on his attendance at a PS-1 congress. Close-up of Arce at the congress in PS-1 colors. Photos: https://twitter.com/, @LuchoXBolivia. The most serious “clarification” given was on “the existence of the pact of impunity”. The directorate first cited the fact that, days after Camacho’s paro had already ended, a handful of MAS senators in the Plurinational Legislative Assembly had joined with the Assembly’s two opposition parties, Creemos (“We Believe”, led by Camacho) and CC (Comunidad Ciudadana, “Citizens’ Community”, led by Carlos Mesa), to pass a new law that set the date of the coming census in March 2024. The reason for this move, which Arce publicly supported, was indeed unclear. The paro had ended; the blockades had been lifted; it seemed like the census date Arce had set for May or June 2024 had been accepted. Why go back and push through, against the wishes of the majority of the MAS caucus, a compromise on the timeline of an extra two months? Just to throw a bone to the opposition? The MAS senators’ split over the vote had led some media to declare a new division within the party between “evistas” (supporters of Evo) and “renovadores” (“renovationists”). The Directorate referred explicitly to these “renovationists”, “known as ‘traitors’ by the people”. Next came reference to the recent release from preventative detention of two military leaders alleged to have taken part in the 2019 coup. The Directorate highlighted their alleged responsibility for the massacre in Sacaba. But more than that, the statement emphasized that, “Up until this very day, the confessed coup-monger [“golpista”] Luis Fernando Camacho has not been brought to trial for the coup d’état”. It’s hard to know how much this list of grievances stirred the party masses or rattled the Ministry of the Presidency. But later that same day, Arce posted pictures from the Bolivian city of Oruro, where he presided over the opening ceremony for a newly built headquarters for a mining cooperative. A column of balloons in stripes of blue, white, and black appeared front and center, and one photo in particular showed a big blue MAS flag waving over the assembled crowd. And exactly eight days after MAS’s National Directorate released its statement, Luis Fernando Camacho was arrested. Luis Arce tweet on his attendance at an opening ceremony for a public works project. Close-up of a MAS flag waving at the event. Photos: https://twitter.com/, @LuchoXBolivia. Aldo González came from the Quillacollo suburb of Cochabamba to the rally in Ivirgarzama, where he wore a baseball cap bearing Morales’s portrait above the slogan “Presidente del Bicentenario 25–30”. (Since Bolivia won its independence in 1825, that would make the victorious candidate in 2025 the “President of the Bicentennial”.) Asked in the hours leading up to the rally to list MAS’s main achievements in its 28-year history, González thoughtfully rattled off a few of the classics. “We have seen,” he said, “the empowerment of women,” explaining that, “Before, women were only dedicated to the home or household. And now we have many authorities—nacional, departmental, municipal—who are women authorities.” He added, “We have been able to recuperate our natural resources, which were privatized by previous governments,” naming specifically, “telecommunications, petroleum, gas.” He noted the “ability to see that people of the lower middle class have been able to obtain various benefits from the government that they never gave us previously.” Asked what the primary challenges for the movement were going forward, he responded without a second’s hesitation: “La unidad.” (“Unity.”) From left: Aldo González. Ramiro Torrico Cardozo. Marcelo Guzmán. Shot of the crowd during the rally, some holding a wiphala with a Che Guevara portrait, others a sign that reads, “‘ESTAMOS POR CONVICCIÓN; NO POR AMBICIÓN’ LEALES SIEMPRE!” (“We are by conviction, not ambition, always loyal!”). Cardozo’s media. Photos: Dan Schoenbaum. As the stadium filled, I interviewed as many attendees as I could between downpours. One man, carrying a bow and arrow, came “from around here, from the Trópico”. One woman, carrying a red flag emblazoned with the face of Che Guevara, came from La Paz. Ramiro Torrico Cardozo, a self-described “activist of the social line”, sold a wide array of DVD documentaries and pamphlets in plastic sheets. The subjects of the movies ranged from the lives of the 18th-century Aymara revolutionaries Bartolina Sisa and Túpac Katari, through the assassination of the 20th-century socialist Marcelo Quiroga, up to the 2019 coup. There was a lot on the 2019 coup. Some people approached me, like Marcelo Guzmán, who quickly identified himself as “Bolivian” and as “Quechua and Aymara,” adding, “So we defend our territory, our homeland, because we are the true owners of this land.” He brought up “traitors […] like Camacho,” but called them “nothing but puppets, marionettes”. He referred to the United States as “the empire”, “an empire that has murdered, the world over, many people who had thoughts about socialism. They have gone to massacre, they have gone to kill, as in Syria, in Afghanistan, in many other countries, to appropriate and take ownership of their wealth: the oil, the gas, and their minerals. In the same way, they have come here to Bolivia.” Though a member of PS-1, Guzmán credited Evo Morales, “un compañero, […] un campesino […] de un pensamiento verdadero revolucionario” (“a comrade […] a campesino […] of true revolutionary thought”) for changing the living situation in 14 years, an achievement that “rightists, capitalists, bourgeois” couldn’t claim in their 180 years in power since Bolivia’s independence from Spain. When I approached groups packed around banners, they usually directed me to a spokesperson. Behind a banner for the Sector Profesional Luis Arce Catacora, several people pointed me toward “la Presidenta”, a woman who identified herself as president of the Drainage Association of Neighborhood Unit 39 of Santa Cruz. Indicating the water flowing through the bleachers over our own feet, she told me about people held hostage by flooding and pressed the need for national projects to lay down pavement and build flood control channels. Banner of Sector Profesional Luis Arce Catacora of Santa Cruz, Bolivia, with the President of the Drainage Association behind in a blue poncho. Flag of Regional Urbana de Cochabamba. Photos: Dan Schoenbaum. The youth holding over a railing a large wiphala with an extra strip of sky blue pushed in my direction a man they called “nuestro líder” (“our leader”). He, Ronaldo Rodríguez Terrazas of the Regional Urbana de Cochabamba, delivered this message for the world: “From this 28th anniversary of MAS-IPSP, we need to make sure that this anniversary is an example of renewal so that, for our various siblings of the neighboring countries, of the six continents that make up our Mother Earth, it is possible to replicate from Bolivia. It is possible to govern, to supply and administer our resources, which in this case are very scarce—like water, hydrocarbon resources, gold, minerals that we have at this time. It is possible to administer them in a better way, so that not only the one percent grabs all the capital in the economic realm. If they see that distribution can happen in this equitable way, where there’s not that difference between classes, then we can be in the democratic moment, when casting your vote will also be equitable as a way to divide the riches that every country has.” Days before the rally, warnings circulated on social media against possible provocations that might occur at or in the lead-up to the event. Spread, as they were, by anonymous accounts, the targets of the alleged plans were unclear. They could be aimed at Morales, against Arce, or as attempts to sow discord within the MAS ranks in general. One Telegram post was originally published in a group called “BOLIVIA INTERNACIONAL” by an admin of that group and then forwarded to MAS-IPSP’s official Telegram channel by an account with the moniker “GHIGHI” and associated in its bio with the Facebook group “Guerreros Samurai”. In this post, a graphic warned against an “autoatentado” (an attack directed against oneself, or a false-flag attack) being concocted by “renovadores”. Though Arce’s name did not appear in the image, the caption accompanying the post read: “*ALERTA AUTOATENTADO ESTARIA SIENDO PLANIFICADO POR RENOVADORES EN CONTRA DE LUIS ARCE EN SU AFAN DE VICTIMIZACION Y DESPRESTIGIO CONSTANTE ATAQUE EN CONTRA DE NUESTRO LIDER Y COMANDANTE EVO MORALES*” (“Alert! False-flag attack is [supposedly] being planned by Renovationists against Luis Arce in their desire for victimization and disparagement [and] constant attack against our leader and commander Evo Morales.”) Telegram post warning of provocation. Photo: https://t.me/masipspoficial, @GHIGHIGS. This kind of opaque online propaganda can be hard to read, and not just for typographical reasons. The bit about “desire for […] constant attack against our leader and commander Evo Morales” implies that Morales is the true target of the planned attack, but the possessive pronoun modifying that “desire” is ambiguous; it’s not totally clear at first glance whether the “desire” is that of the renovadores or that of Arce. The “self-attack” is explicitly described as being “against Luis Arce”, but if it is a “self-attack”, is there not an implied connection between the object of the assault and the one committing it? The only apparent disruption that occurred at the rally was as fleeting and mysterious as those anonymous internet alerts. It happened right at the rally’s start. Morales and other members of MAS’s leadership were already onstage, but President Arce and his vice president, David Choquehuanca, had not yet entered. The celebration opened with the singing of the Bolivian national anthem. Immediately after the anthem, an announcer requested a minute of silence in remembrance of “the heroes who have given their lives in defense of our true democracy, in defense of our natural resources and the coca leaf”. About halfway through this minute of silence for the movement’s martyrs, a noticeable disturbance broke out in the front right corner of the stadium’s stands. All of a sudden, in that section, flags waved, confetti was thrown, and clear chants could be heard of, “¡Lucho! ¡Lucho! ¡Lucho!” As people nearby began to realize what was happening, areas of the crowd surrounding that section started to respond, apparently mostly by chanting, “¡Evo! ¡Evo! ¡Evo!” The “¡Evo!” chants spread so quickly that they appeared to drown out the initial “¡Lucho!” chants. This made it impossible not to wonder if the point had been to provoke the “¡Evo!” chanters into this unseemly spectacle. The press that had been huddled in front of the stage responded by rushing to the affected area. Evo himself watched silently with a disapproving look on his face. Disruption in crowd during moment of silence at rally’s opening. Reaction from stage. Photos: Dan Schoenbaum. Within another thirty seconds, without acknowledging the scuffle, the announcer resumed the program, and the chanting on all sides died down. Arce and Choquehuanca walked onto the stage and greeted the party leaders already present. Maria Eugenia Ledezma, president of the Coordinating Committee of the Women of the Six Federations of the Trópico de Cochabamba, launched into her opening remarks, and the interruption faded into the background. But in that background it hung for the rest of the event, and the event’s keynote speaker would not let it go unremarked. The day’s lineup included six speakers from party leadership. After Ledezma, they were: Ramiro Cucho, executive of CONAMAQ (Consejo Nacional de Ayllus y Markas del Qullasuyu; “National Council of Ayllus and Markas of Qullasuyu”), representing traditional Indigenous governing structures. Ever Rojas, executive of CSUTCB (Confederación Sindical Única de Trabajadores Campesinos de Bolivia; “Single Syndical Confederation of Rural Workers of Bolivia”). Rolando “Flaco” Borda, executive of the COD (Central Obrera Departamental; “Departmental Workers’ Center”) of Santa Cruz, a regional trade union federation that forms part of the national equivalent, COB (Central Obrera Boliviana; “Bolivian Workers’ Center”), a staple of Bolivian labor politics since the country’s 1952 social revolution. Luis Arce. Evo Morales. Maria Eugenia Ledezma. Ramiro Cucho. Ever Rojas. Rolando “Flaco” Borda. Luis Arce. Evo Morales. Photos: Dan Schoenbaum. The slate was broken up by performances from the Cochabamba musical group Arawi, who played their signature song “Somos MAS” (“We Are MAS”), as well as by the reading of a “Poema antiimperialista” (“Anti-imperialist poem”) by a young girl, Jimena Cartagena. The opening line went, “Damned imperialist gringo. Sick capitalist. Fascist, racist, colonialist, coup-monger, imperialist. Enemy of humanity, you killed the dreams of humanity.” The poem culminated: “Somos anticapitalistas, somos antiimperialistas, nunca nos rendimos y jamás nos rendiremos. Revolución democrática y cultural para salvar a la humanidad de la crisis social, paz con justicia social. ¡América plurinacional!” (“We are anticapitalists. We are anti-imperialists. We never surrendered, and we will never surrender. Democratic and cultural revolution to save humanity from the social crisis. Peace with social justice. Plurinational America!”) “Unity” was a theme in many of the speeches. Ledezma sandwiched her pitch for unity between highly targeted pressuring of Arce: “We continue to ask for justice. We see that the golpista Camacho still has not been sentenced. We know that he’s been detained, but he hasn’t been sentenced. And we are going to ask for that, brother President Lucho, that there has to be justice, sisters and brothers. There cannot be another coup d’état. It also pains us that those golpistas, who have stepped on us and killed us, still are working in the ministries. That pains us a great deal, sisters and brothers. Brothers, on this anniversary, we must maintain unity, the nine departamentos of Bolivia, as Political Instrument and as owners of the Political Instrument, sisters and brothers. But also, brother President Lucho, we want to say: Why are you all punishing us with the price of the coca leaf? We know quite well, that crisis has exhausted us enough. We believe that, on this anniversary, the best gift would be for you to, please, raise the price of the coca leaf.” Cucho expressed his satisfaction in celebrating the day “to say to the whole world that Bolivia and all the social organizations are more united than ever to overthrow the capitalist empire, damn it!” He said that “today we are affirming this true unity. Because you and all the others, we have been in the streets, recovering the peoples’ democracy. We have been in the massacre when the government de facto persecuted us politically. And thanks to the unity of the Bolivian people, we have recovered the peoples’ democracy. By those actions, we have demonstrated that true unity.” Rojas blamed the Right for trying to divide the party, insisting, “Here there is unity. There is no division in our process of change [“proceso de cambio”], in our Instrument.” He ended his speech, “Help me to say: Long live our Plurinational State of Bolivia! Long live our President Lucho and David! Long live our brother Evo Morales! Long live our senators! Long live our deputies! Long live MAS-IPSP! And wañuchun yanqui!” (Quechua: “death to the yankees!”) Borda rejected the opposition between MAS and his home departamento, declaring, “¡El MAS es cruceño!” (“MAS is of Santa Cruz!”) He continued, “The lodges don’t like that,” referring to the pseudo-masonic secret societies of which many of Santa Cruz’s conservative elites have been documented members, including Camacho. “The power centers don’t like that. MAS was born in Santa Cruz!” Indeed, the March 26 founding that the rally commemorated took place in Santa Cruz. Soon after Borda’s speech, the announcer told the story of a caravan of bicyclists that rode their way to that founding meeting in 1995. He said that when they started their trip, they were maybe 30 or 50 people, and by the time they arrived in Santa Cruz, they had amassed more than 200 participants. According to the announcer, some of those founding cyclists were to enter the stadium and take a ceremonial ride over the field. Then came the two big speeches. Accompanied by fireworks and a moderate drumbeat of “¡Lucho! ¡Lucho! ¡Lucho!”, President Arce greeted the crowd, “¡Buenas tardes, masistas!” In an address that lasted fifteen minutes almost to the second, he used the word “unity” nine times. The first time, he introduced it as “a requirement sine qua non” for the continuation of the construction of “our Plurinational State”. In a nod to Bolivia’s history of struggle beyond MAS’s 28 years, the president recounted: “There were Indigenous, Katarist, indigenist movements. There were also workers’ movements, movements led by the socialists, by the communists, by the Guevarists. They were present too, even including nationalism, to hoist the flag of revolution. But it wasn’t until 2006, when this revolutionary process consolidated itself, when, with our brother Evo at the head, when, in a historic fashion, we won the elections of 2005, that this revolutionary process initiated itself under the leadership of MAS-IPSP.” The consciously Marxist thread in Arce’s thinking came through clearly. At one point, he explained, “Differences are always going to exist, because they are, rather, the product of the advance of the dialectical process that our Political Instrument possesses.” In almost the next breath, he quoted “el Comandante Fidel Castro” as saying, “We must have a storm of ideas, a battle of ideas.” With this Castro quote as a jumping off point, Arce built up to what seemed to be the thesis of his address, that “there can be pluralism of ideas, but there must be one single ideological unity in our Political Instrument.” He made this turn of phrase into something of a slogan, declaring at one point, “Pluralism of ideas and ideological unity in MAS-IPSP!” This distinction might have come across as more solid if the president hadn’t a few minutes later mixed up his own terms: “We can have ideological differences—or, excuse me—differences of ideas, but we are not going to have differences in our action against the Right.” Toward the end of his speech, after going over the crimes of the coup regime, including their imposition of an “economic siege” on the Trópico de Cochabamba, their torture of MAS leaders, and the poor state in which they left the economy, Arce took a sudden international turn, saying, “Sisters, brothers, the moment arrives to export our Democratic and Cultural Revolution to all of Latin America. That is the challenge for our Political Instrument.” To this, the crowd barely responded. The ecstasy with which they met Evo struck a sharp contrast. Morales spoke for just over 45 minutes. Immediately after his opening hellos, he spoke on the chanting issue: “Although I come with a friendly greeting, some come to yell. If they don’t yell ‘Lucho’, they’re going to lose their jobs. Yell ‘Lucho, Lucho’ so you don’t lose your jobs.” He smiled. “We are informed.” The crowd responded by laughing and chanting, “¡Evo! ¡Evo! ¡Evo!” Morales’s smile widened. “No, no, no!” he said, waving his finger. “You’re doing it wrong! Be careful, you’re going to lose your jobs.” Openly playing on Arce’s long list of historical movements, Morales recalled: “When I was a child, adolescent, I heard: indigenist, Katarist movements, MITKA-1, MITKA-2 [factions of the Movimiento Indio Túpac Katari]. Because it was a base to drive a political movement. But it must also be remembered, sisters and brothers, it’s not that there was a lack of Left parties. There were Left parties—socialists, communists. But that traditional Left was without Indians, without the Indigenous movement.” Taking an explicit dig at PS-1, Morales dusted off a story he’s been telling for years, about a time former PS-1 candidate Roger Cortez called him in and said, “Evo, neoliberalism is like a locomotive. If you get out in front of it, it’s going to crush you, and all that will be left is neoliberalism. Better to get onboard neoliberalism, on that train.” Hitting every note from dignified quiet to a voice-cracking cry of defiance in one line, Morales let the crowd know, “I told him, ‘No. Though it crush me, we are going to fight against that Right Wing, against neoliberalism, against national sell-outs [“vendepatrias”], against national enemies [“antipatrias”]!’” With more of a teacher’s tone, he went on, “I continue to be convinced, I am still convinced that our political movement MAS-IPSP is unique in the world. Why? Why unique in the world? […] I traveled almost over the whole world. All the countries of the world have their Left party. Their Left party, who makes it? A group of professionals, political scientists, who then say, ‘This is the party of poor people, it’s the party of the humble people [“la gente humilde”].’ And this wonder, in Bolivia, under the threat of extermination, hated, despised, we made our Political Instrument. For this reason is MAS-IPSP unique in the world, sisters and brothers.” Morales reading printed news stories from folders onstage. Photo: Dan Schoenbaum. He briefly recounted the story that led to MAS’s founding—how the social organizations led marches against the neoliberal government’s “Option Zero” plan to eliminate coca production; how they extracted commitments from the government; how they met in the nearby Trópico town of Eterazama, in the town’s coca market, in December 1994 to address the fact that none of those commitments had been fulfilled; how they planned a convention for March 1995 in Santa Cruz to found a political instrument of their own. He then picked up a pair of folders stuffed with papers. Holding the pages up to the crowd and cameras, he read from printed-out news stories. First came the record of the Minister of Government’s contact with the DEA. Next Morales quoted, apparently by way of Sputnik News, Donald Trump’s statement to the first ever CPAC meeting in Mexico that, “We must stop the spread of socialism and just not allow it to continue to sweep across this region, or,” and here Morales turned and added extra emphasis, “our land.” He went on to reference a recent interview in which General Laura Richardson of US Southern Command (SOUTHCOM, which, Morales noted, “earlier was called the School of the Americas, as the School of Assassins”) described the US military’s coordination with US embassies and transnational corporations in Latin America to secure access to lithium and other natural resources. After flipping through page after page of evidence of the US government’s hostility to Evo personally and his movement generally, Morales said, “There are more than enough reasons, heaps of reasons to be united, but united against the principal enemy. United, not to run a campaign against Evo or against the leaders, not to persecute comrades.” With the folders still in hand, Morales turned to Arce. “Let’s be honest,” he said. “I greatly regret, brother Lucho, some ministers are going to have to read Article 8 of the constitution, the ama suwa, ama llulla.” Article 8 of the 2009 Constitution of Bolivia names the “ethical-moral principles of the plural society”. The first of these is the traditional Quechua greeting that dates at least to the Inca period, “Ama quilla, ama llulla, ama suwa.” (“Don’t be lazy, don’t be a liar, don’t be a thief.”) So Morales implied these ministers were everything but lazy. Later, Morales returned to the theme of ministers, saying, with his back to the crowd, “Lamentably, some ministers are not militants. They come from the MNR [Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario; “Revolutionary Nationalist Movement”], and they are damaging Lucho. They are destroying MAS.” He turned back to the crowd to add, “And you all are going to defend, you all are going to defend our Political Instrument.” At various points when the subject of ministers came up, calls could be heard from the crowd of, “¡Cambio de ministros!” (“Change of ministers!”) Morales’s critique of Arce’s economic management is worth quoting at length: “It’s necessary to leave behind the economic team, the orthodox, the conservatives, with their pretext of lowering inflation. In the end, avoiding inflation, what does that do? All it accomplishes is submission to the fiscal discipline of the International Monetary Fund. Protect the macroeconomy to punish the small producers, the poor people. That is what we are seeing. Clearly it’s important that there not be inflation, that there not be deficit, but without economic expansion, it’s necessary to inject economic movement, money, small and medium-sized projects. At this time, brother Lucho, we are seeing a policy of austerity.” If at the start he was teasing, by the end, Morales was channeling fury. “Talk of unity, unity, unity, sisters and brothers, what does it mean?” he demanded. “Unity, first, with respect to the statute of MAS-IPSP. There we’ll see that unity. If you want unity, sisters and brothers,” he said while turning to face the leadership onstage, “as some social movements request, convoke the National Directorate.” Turning back to the crowd, he shouted, “They never convoke the National Directorate. What unity are we talking about?” Pointing to the bleachers, he admitted, “Some of you are a little bewildered today. The dirty, dishonest campaign… I am used to putting up with this from the gringos, from the Right, but it cannot be from some of our own brothers. I defend myself from the front. I am no coward. And some people attack like cowards on social media. That is cowardice.” Morales also took a swing at international politics in his last couple of minutes, but it came with explicit reference to a possible return to national candidacy. He claimed that when he saw Alberto Fernández, the current president of Argentina, at the III World Forum on Human Rights only two or three nights previously, Fernández told him, “Vamos a relanzar UNASUR,” and, “Ojalá vuelva UNASUR.” (“We are going to relaunch a blue,” and, “Hopefully a blue will come back.”) Morales promised, “If a blue launches themself anew, goes into operation, as a blue, I will make a strategic accord with China, India, Indonesia, Russia, certain Arab countries, so that half the population of the world would be our strategic allies to sell our products.” With one last battle cry, the president of MAS said, “I want to call on my brothers of the campo. Let us recover in order to be the moral reserve of humanity as the native, Indigenous, campesino movement. No brother in leadership will destroy that moral reserve.” By the end of Morales’s speech, much of the leadership onstage looked like they wished they could’ve stayed home that day. But the crowd was euphoric. All Arce could do was hang his head and lift the MAS flag for each one of Evo’s closing slogans: “¡Que viva nuestro proceso de cambio! ¡Que viva la Revolución Democrática y Cultural! ¡Patria o muerte! ¡Patria o muerte! ¡Que viva el Estado Plurinacional!” When he returned to his seat, Morales spent a full minute wiping the sweat from his face, neck, and forearms with a blue towel. When the rally ended, the party leaders onstage patted each other on the back. Soon people from the field started to climb onto the platform. At first, security pushed them back. But the crowd still in the pit jeered at that, and eventually, more and more people hopped up. Their feet were soaked through with mud, their legs splattered up to the knees. As the throng onstage got thicker, it became hard to tell how many were shaking hands, snagging selfies, or soliciting autographs from each individual party figure, but it was clear that the overwhelming majority were there for contact with Morales. The crush only started to disperse once the guards made a show of slipping the leadership out the back. Evo had left the building. Crowd takes the stage at the rally’s end. Photo: Dan Schoenbaum. In line for the bus back to the city of Cochabamba, a young man who later told me he was twenty-two years old clocked me as a foreigner and asked me where I was from. We had a lot of questions for each other, and we ended up sitting across the aisle from one another on the seven-hour ride home. Until he and his seatmate, a woman who was a stranger to him and looked to be in her thirties, fell asleep, the three of us shared our experiences, I from the United States and they from Bolivia. Once he had confirmed that I was coming from the same rally he had just attended, the young man asked me what I thought of Evo. I said, “He’s like a rockstar.” I asked him, “What do you think of Evo and Arce?” He said, “Oh, I support Evo.” He asked me which one I preferred. I asked, “Does it have to be a choice?” He shrugged and answered, “Everyone has their own opinion.” He told me Evo spoke for the “gente humilde” and cited the construction of Cochabamba’s “doble vía” (double-lane highway) as one of Morales’s great accomplishments. I asked him if he thought Morales would stand as a candidate in the next election. He told me, “Definitely.” He said that a lot of people would demand it and cited the same “Evo 25–30” materials that I had seen in Sacaba and now Ivirgarzama. After probing me on how I had studied Spanish, the woman in the next seat over asked if I had learned any Quechua. I told her not really but that I desperately wanted to. I asked her if Quechua was her first language, and she told me yes, it was. She asked the young man in between us if it was his first language too. He said, “Sí, soy del campo.” He asked me if it was true that in the United States, the harder you work, the less money you earn. He wanted to know if there was poverty in the US or the kind of social movements that exist in Bolivia. He asked me if it was true that the US supported Ukraine in the current war. I asked the two of them what they thought about the war in Ukraine. The woman said, “Que Estados Unidos quiere matar a dos.” (“That the United States wants to kill both sides.”) As with the December rally in Sacaba, the highest drama around the celebration in Ivirgarzama came in the days after. A week after his speech, almost to the minute, on April 2, Morales tweeted maybe his most incendiary statement yet: “El MAS-IPSP no está en el gobierno.” He wrote: “MAS-IPSP is not in the government. It is totally false that we have asked for ministries. When we won the elections, I explained and suggested to brother @LuchoXBolivia that he should prepare his cabinet with people who would respond to him. I didn’t ask for any position, nothing. “At the concentration for the 28th anniversary of MAS-IPSP, the grassroots requested that Lucho has to improve his cabinet to have good management and terminate his [current] government. He is responsible for having included ministers who are not of MAS-IPSP and who try to defenestrate leadership and divide us” Whether my bus-mate is right and Morales makes a run for the bicentennial presidency, MAS seems to be on a path to a period of serious conflict with little chance of turning back. If history is any indication, the people like that bus-mate, the working masses of the party and country, will be the decisive factor in how that conflict resolves. As he ended his speech in Ivirgarzama, Luis Arce said that it was clear “that this process of change is already a patrimony of the Bolivian people.” Whatever happens in the next couple of years, it seems unlikely to change that. AuthorDan Schoenbaum is a writer and researcher based in Cochabamba, Bolivia. He has a background working for immigrant rights and liberation in Chicago, Illinois, and his current areas of focus are the history, politics, and regional integration of Latin America. Archives September 2023

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed