|

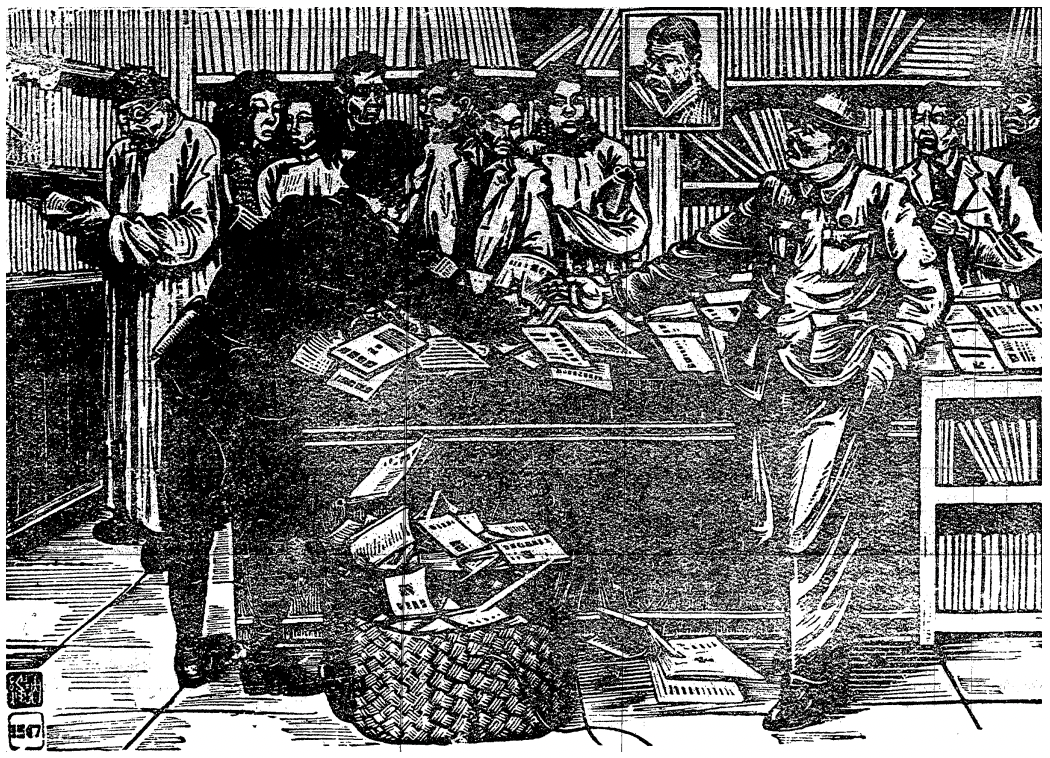

12/5/2022 The Necessity of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat:: a Litmus Test for Marxism By: Teo VelissarisRead Now‘Kuomintang Burns Books’ [Yang Na-Wei – Harian Rakjat, September 1, 1963] What was Marx’s main contribution in the history of ideas and the struggle for socialism? In a letter from 1852, Marx himself provided a remarkable answer: And now as to myself, no credit is due to me for discovering the existence of classes in modern society or the struggle between them. […] What I did that was new was to prove: (1) that the existence of classes is only bound up with the particular, historical phases in the development of production (2) that the class struggle necessarily leads to the dictatorship of the proletariat, (3) that this dictatorship itself only constitutes the transition to the abolition of all classes and to a classless society. Since then there has been a struggle among socialists to understand the meaning of a notion such as “the dictatorship of the proletariat” and the reasons that led Marx to adopt it. Certainly, it was understood and anticipated that a socialist revolution would most probably face resistance from a minority that would struggle to defend its vested interests against the majority’s will for change; and hence the latter would have to suppress the former. But why not call it a democracy of the proletariat then, instead of a dictatorship? When Marx and Engels, themselves, had to clarify what they meant by dictatorship of the proletariat, they pointed to the Paris Commune of 1871,1 which was generally conceived, and rightly so, as democratic par excellence by the socialist camp. Their invocation of the Paris Commune has not sufficed to clear up the confusion. One must delve into the details of Marx and Engels’ arguments in order to understand the meaning of the dictatorship of the proletariat. For them, the Commune was “the political form at last discovered under which to work out the economical emancipation of labor.” But they understood the Commune not as the end of the road but rather the beginning, not just an end in itself but also an instrument to help achieve a higher purpose: “The Commune was therefore to serve as a lever for uprooting the economical foundation upon which rests the existence of classes, and therefore of class rule.” This is crucial because for non-Marxian socialists, a successful revolution already signifies the uprooting of the aforementioned economic foundation. But, for Marx, the revolutionary Commune would facilitate labor’s emancipation, without yet being labor’s emancipation in the flesh. And the same goes for the dictatorship of the proletariat in general: Between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat. Therefore, the Commune, however democratic and desirable, couldn’t avoid remaining a state, not yet communist; it wasn’t something out of this world, unaffected by capitalist reality, as if it had landed in Paris from an alien non-authoritarian communist planet. Revolutions are instigated by human beings, who are the products, “down to their innermost core,” of the same problematic society they want to change.2 So, the Commune was rather “the direct antithesis to the empire.” The “empire” (i.e. Bonapartism) was the authoritarian form that politics assumed under conditions of capitalism post-1848 (all politics, even democratic politics, or, rather, especially democratic politics). It was “the only form of government possible at a time when the bourgeoisie had already lost, and the working class had not yet acquired, the faculty of ruling the nation.” If Bonapartism was the dystopian expression of the 1848 workers’ demand for a “social republic,” the Commune “was the positive form of that republic.” The Commune emerged within this void of authoritarian disintegration and the crisis of capitalist politics but was at least “positive” in pointing beyond it by allowing the working class and the democratic majority of society to assume responsibility for it. For Marxism, the dictatorship of the proletariat signifies the condition when the working class has finally acquired the faculty of ruling the nation3 – even though only in order to ultimately make such a “ruling” redundant.4 The proletariat wouldn’t follow the example of the bourgeoisie in its attempt to acquire political power.5 Contrary to various anti-Marxist clichés, Marxism did not liken the revolutionary development of the working class within the womb of capitalism to the development of the bourgeoisie within the womb of feudalism. According to Rosa Luxemburg, bourgeois society is decisively distinguished from other class societies because in it “class domination does not rest on ‘acquired rights’ but on real economic relations.” Wage slavery is not expressed in laws, hence wage slavery cannot be suppressed by means of “legislation.” She cites key parts of the Communist Manifesto to make her case: All previous societies were based on an antagonism between an oppressing class and an oppressed class’. But in the preceding phases of modern society this antagonism was expressed in distinctly determined juridical relations and could, especially because of that, accord, to a certain extent, a place to new relations within the framework of the old. ‘In the midst of serfdom, the serf raised himself to the rank of a member of the town community. I really cannot overemphasize the significance of this point, which many on the Left—Marxist or otherwise—still fail to comprehend: only prior phases of modern society could accord “a place to new relations within the framework of the old.” For these leftists, similarly to the bourgeoisie within feudalism, it is somehow possible for the proletariat to first develop itself and become socially empowered within capitalism, and when this development is complete and the situation is ripe, only then seize political power. But in capitalism the situation can never be ripe enough for the proletariat, which remains permanently vulnerable to the economic conditions and their crisis. As Luxemburg explains, it’s not the law but rather “poverty, the lack of means of production, [that] obliges the proletariat to submit itself to the yoke of capitalism.” Consequently, if we remain within the framework of bourgeois society one cannot expect the law to be able to give to the proletariat the means of production. Under capitalism, wage slavery cannot be accommodated by existing legal relations, because it isn’t a juridical but an economic relation. As a result, even with the most stringent labor laws, this will not impinge on the extraction of surplus value and the necessity of surplus labor. Luxemburg goes on to extract the quintessence of Marxism on this issue, highlighting one of the peculiarities of the capitalist order: Within it all the elements of the future society first assume, in their development, a form not approaching socialism but, on the contrary, a form moving more and more away from socialism. Production takes on a progressively increasing social character. But […] It is expressed in the form of the large enterprise, in the form of the shareholding concern, the cartel, within which the capitalist antagonisms, capitalist exploitation, the oppression of labour-power, are augmented to the extreme. […] In the field of political relations, the development of democracy brings – in the measure that it finds a favourable soil – the participation of all popular strata in political life and, consequently, some sort of ‘people’s State.’ But this participation takes the form of bourgeois parliamentarism, in which class antagonisms and class domination are not done away with, but are, on the contrary, displayed in the open. Exactly because capitalist development moves through these contradictions, it is necessary to extract the kernel of socialist society from its capitalist shell. Exactly for this reason must the proletariat seize political power and suppress completely the capitalist system. Seizing political power and completely suppressing the capitalist system: the dictatorship of the proletariat in a nutshell! Again, an invaluable Marxist lesson: development within capitalism, even when it appears to bring one closer to realizing one’s ideals, is actually moving one further away from them at the same time. The proletariat must take responsibility for the aforementioned contradiction and prioritize its self-organization through parties and institutions in order to first seize political power. Only then can it start seriously placing new economic relations in the framework of the new political order (not the old). Marx didn’t fail to underline this aspect himself, stating that the “social revolution of the nineteenth century cannot take its poetry from the past but only from the future.” The bourgeois revolutions appeared as the legitimate political capstone of social evolution, whereas the socialist revolutions will always appear as socially immature, untimely, and illegitimate. The proletariat finds that it must attain political power to address the problem of capital. This means that the proletariat’s political revolution—unlike that of the bourgeoisie—is the beginning, rather than the culmination, of the revolutionary process. It is at this point that most anti-Marxist socialists begin to object. They expect Day One of the revolution to be close to idyllic, and certainly not dictatorial at all, revealing their basically bourgeois conception of revolution. According to the anti-Marxist socialist, the proletariat can achieve the same crucial preliminary gains under capitalism that the bourgeoisie achieved under feudalism (which is an astonishing apology of capitalism as a system that enables the flourishing of the economy and culture, and, in the final analysis, permits the freedom of the class that it oppresses). This leads to the impasse of pre-figurative initiatives to create within capitalism proto-forms of socialism that will gradually grow and challenge competitively the capitalist system without the unfortunate need to engage in mass politics from a working class perspective; these initiatives usually end up feeding into and being subordinated to so-called progressive capitalist policies. The proletariat is thought to thereby instantly remove the privileges of its enemies in order to achieve immediately a non-dictatorial reality.6 But the proletariat’s enemies will always feel entitled to appeal to their abstract right in order to legitimize their power. Such appeals are commonplace under “normal” capitalist conditions and will proliferate in moments of political crisis. Dictatorial force thus seems unavoidable to decide the outcome of the struggle, as Marx remarked when he was addressing the antinomy of “right against right” in Das Kapital.7 Given these contradictions and antinomies, every effort by the working class to seize political power will be denounced by the establishment as barbaric and dictatorial (even if it is supported by the majority), and its effort to create a new legality will always be vehemently opposed by the current legality. This crisis of legality is already manifest in capitalist democracy. For example, during the first years of its financial crisis, circa 2010, Greece had to impose unprecedented austerity measures, and the legality, or the constitutionality, of the relevant memoranda of austerity was challenged immediately even from within the bourgeois democratic camp. But this was never and has never been addressed as an abstract question of law, legality, and justice, but rather as a series of exceptional political, economic, and legal measures in a state of emergency, in view of the country’s objective of remaining in the European Union and the Eurozone. The austerity measures had to be implemented coercively as a matter of life and death, and the question of their legality was to be adjudicated on an ad hoc basis; legality was subordinated to politics. The issue had to be resolved dictatorially, with the special bodies of armed men in the street enforcing the decisions of the elected establishment. The chief example of how capitalist democracy and legality contradict each other was of course exhibited by the fate of the referendum against the austerity measures, first the one that was canceled, and then the one whose result was ignored. Even the explicit preference of the majority on a single issue didn’t appear as a legitimate challenge to the political status quo. These problems cannot be resolved by simply appealing to democracy, because under conditions of capitalism and especially post-1848, democracy itself appeared unable not only to address the social crisis but also to express the potential to move beyond it. Famously, as we already mentioned, the cry of the Parisian workers in 1848 was not just for democracy but for “république sociale,” for democracy adequate to societal needs. Capitalism divided the political and economic aspects of life in an unprecedented manner, turning the one against the other (and the freedom and rights of the individual against the freedom of the collective), rendering acute what was now expressed as the competition between democracy and liberalism: the latter two instead of enhancing each other, appeared now as undermining and violating each other, eager to “correct” each other’s deficiencies.8 Marx wasn’t nostalgic at all and didn’t pursue a (pseudo-)solution of this problem in pre-capitalist terms. “In the Middle Ages”, he wrote, “popular life and state [i.e., political] life were identical. Man was the actual principle of the state, but he was unfree man. It was therefore the democracy of unfreedom, accomplished alienation.” The desperate need for democracy circa 1848 (persisting till our present) was an index of regression, a cry for help within social disintegration and crisis, not an achievement of progress. Marx tried to avoid naturalizing this cry for help from a democratic state in the role of deus ex machina, and to grasp it critically: the need for democracy was attesting not to the presence but to the lack of an “association, in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all,” as the Manifesto had succinctly described the possible overcoming of both democracy and liberalism, beyond classes and class antagonisms. Ignoring these sorts of contradictions that are already at play within any capitalist democratic legality and succumbing to “the lofty heaven of [an] ideal republic,” can lead to disastrous political paralysis. To cite an example, it is well known that the Spanish anarchists defended Barcelona and Catalonia from the fascist coup in July 1936. What is less well known is that when the fascists were ousted, the petty bourgeois democrat governor of Catalonia, Luis Companys, in a state of awe and fear, said to the representatives of the CNT: You are now in control of the city and Catalonia because you alone routed the fascist militarists. Understanding that the CNT/FAI had de facto control indeed, some anarchists proposed that the unions should take power and overthrow the Generalitat and impose their anarchist vision of libertarian communism. But many others argued that this would be a refutation of their vision, a dictatorship imposed by a minority (CNT/FAI had a simple but not a super-majority of 50+1% among the workers); that it would mean the imposition of an anarchist dictatorship, a Bolshevik style coup. So, after a heated debate, the Barcelona labor council voted against the option of taking power. By choosing not to transfer power to the workers’ new-born institutions and by disavowing political power as authoritarian, the anarchists facilitated the dictatorial concentration of power in other dubious institutions and agents. By attempting to avoid the problem of power and the problem of the state, the anarchists became adjuncts in other, far worse dictatorships—of the bourgeoisie, the reaction, the minority. (It is not as if there was a choice beyond dictatorship – the only choice was who was going to assume responsibility for the prevailing authoritarianism and how it was going to be enacted in practice). The CNT/FAI leadership declined the dictatorship of the proletariat but accepted the subordination of the newly formed revolutionary militias to the bourgeois state. In exchange they were granted four government ministries in a popular front and a bourgeois democratic government that ended up dictatorially suppressing workers itself (see the events of the Barcelona insurrection in May 1937).9 The purpose of this short digression is not to single out anarchism as problematic and the anarchists as the sole “apostles of political indifferentism”; Marxists were also affected by paralysis and they denounced revolution by denouncing the dictatorship of the proletariat (see for example the events in Germany, 1918).10 Rather, anarchism is an object lesson in the inevitability of authoritarianism in an authoritarian world, no matter how many times one may denounce it ideologically. It is no surprise, then, that the same anarchists who fiercely attack Marxism for authoritarianism so often end up accusing one another of “crypto-Leninism.” It is interesting to read how Luxemburg assessed, in Marxist terms, Lenin’s stance towards this problem of possible paralysis in revolutionary conditions: It is not a matter of this or that secondary question of tactics, but of the capacity for action of the proletariat, the strength to act, the will to power of socialism as such. In this, Lenin and Trotsky and their friends were the first, those who went ahead as an example to the proletariat of the world; they are still the only ones up to now who can cry with Hutten: ‘I have dared’! …these German Social-Democrats have sought to apply to revolutions the home-made wisdom of the parliamentary nursery: in order to carry anything, you must first have a majority. The same, they say, applies to a revolution: first let’s become a ‘majority.’ The true dialectic of revolutions, however, stands this wisdom of parliamentary moles on its head: not through a majority, but through revolutionary tactics to a majority – that’s the way the road runs. Their Marxism, their subscription to the necessity of the dictatorship of the proletariat, enabled Lenin and the Bolsheviks to strengthen the proletariat’s capacity for action in its struggle for socialism.11 The reader shouldn’t conclude in a voluntaristic fashion that the conditions are always ripe for revolution; the point is rather that even when conditions may be ripe, strong ideological obstacles, like the allergy to the idea of the dictatorship of the proletariat, may ultimately lead to disastrous paralysis. The disavowal of the dictatorship of the proletariat prepares the way for such an abandonment of revolutionary responsibility. Because, like it or not, all big political shifts in mass capitalist politics raise the specter of dictatorship, and thinking otherwise is the hallmark of bankrupt liberalism. Capital is pathological and revolution is a symptom of capital.12 So, the key is not to just denounce social authoritarianism but to assume responsibility for it and to try to channel the authoritarian energy toward revolutionary goals through democratic means and ends (thus Lenin for example didn’t denounce war but aimed to turn the world war into a civil war). Marx sarcastically noted that non-Marxist social democrats and democratic socialists only cared to feel that they were on the side of eternal justice and all the other eternal truths, no matter if the things that matter most, power and success, were never on their side. Returning to Marx and Engels, while they defended and praised the Paris Commune, they didn’t fail to criticize the hesitancy of its leadership on key moments of their struggle: In their reluctance to continue the civil war opened by Thiers’ burglarious attempt on Montmartre, the Central Committee made themselves, this time, guilty of a decisive mistake in not at once marching upon Versailles, then completely helpless, and thus putting an end to the conspiracies of Thiers and his Rurals. And: The hardest thing to understand is certainly the holy awe with which they remained standing respectfully outside the gates of the Bank of France. This was also a serious political mistake. Both of these actions, had they been attempted, would have been denounced by many as dictatorial, in the sense that it would have appeared that the Commune was crossing the line by weighing in arbitrarily on the national level without a pre-given relevant political legitimacy. The Commune succumbed to these reservations; its leaders lacked the strength to act. Engels also wrote in regard to this issue that a victorious party in a revolution: must maintain this rule by means of the terror which its arms inspire in the reactionists. Would the Paris Commune have lasted a single day if it had not made use of this authority of the armed people against the bourgeois? Should we not, on the contrary, reproach it for not having used it freely enough? These criticisms should be kept in mind because Marx and Engels admired exactly all of the characteristics of the Commune that were more democratic compared to the bourgeois parliaments, not less. Engels summarized Marx’s description of how the Commune was shattering the former state power, that was functioning as the master of society, and was replacing it by a new and really democratic state that was becoming now, for the first time, the servant of society: “It filled all posts – administrative, judicial, and educational – by election on the basis of universal suffrage of all concerned, with the right of the same electors to recall their delegate at any time. And in the second place, all officials, high or low, were paid only the wages received by other workers.”13 Hal Draper,14 in his monumental work on the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat describes an incident during the last days of the Commune: the majority proposed to create a five man uber-authority (a dictatorial committee of public safety) and all those from the minority who were Marxists or influenced by Marx stood against it – not accidentally. The Commune should have exercised its authority more readily and freely, but only if it was legitimized through the extremely democratic institutions of direct control and recallability of representatives that it created. But, crucially, Commune’s legitimization was also stemming from the way it was fulfilling the desiderata of liberalism, not just democracy: The Commune made that catchword of bourgeois revolutions – cheap government – a reality by destroying the two greatest sources of expenditure: the standing army and state functionarism. Its very existence presupposed the non-existence of monarchy, which, in Europe at least, is the normal incumbrance and indispensable cloak of class rule. […] The Commune intended to abolish that class property which makes the labor of the many the wealth of the few. It aimed at the expropriation of the expropriators. It wanted to make individual property a truth by transforming the means of production, land, and capital, now chiefly the means of enslaving and exploiting labor, into mere instruments of free and associated labor. Draper compellingly shows that by the dictatorship of the proletariat Marx meant the political rule of the proletariat and, more so, a class dictatorship rather than an individual or clique dictatorship (via class representatives that would rule without accountability). Draper exposed how other socialists in Marx’s time, including Blanquists, anarchists and others, were pursuing a dictatorship over the proletariat, or some sort of educational dictatorship: the people, the masses, were assumed to be corrupted by the social order, and they had to be saved despite themselves with the help of the good and wise guys of the revolutionary elite – rings a bell comparing to how large segments of the Left today treat the masses? The term, according to Draper, was more about the class content of a new revolutionary regime, not about the particular type of the new political institutions. It was another way to describe what we would otherwise just call a worker’s state. But Draper, in drawing these important conclusions, neutralized Marx’s and Engel’s critical approach to the worker’s state itself. The point is that states are always more or less dictatorial, in a negative sense; and this stands even for the most democratic ones, when they exist within class society, and in conditions of capitalism or conditions still under the influence of capitalism. The state equals use of forcible coercion, coercive rule; it’s an organized machinery of suppression, even if its special bodies of armed men work genuinely in the name of the majority.15 Draper, thus, leaves us rather unprepared to understand why for Marxism the workers’ state is transitory and needs also to be overcome, and why for Marx there is a crucial distinction between a still pathological and problematic “first phase of communist society” and a “higher phase of communist society” emancipated from capital.16 The use of the term “dictatorship of the proletariat” by Marx and Engels wasn’t just a rhetorical device to tactically win over the Blanquists, as Draper suggests (which is unlikely because they kept using the term even after the decline of Blanquism). In my opinion, it was a conscious choice on their part in order to signify the authoritarianism still at play during the revolution and the first phase of communist society, which Marxists needed to be self-conscious of in order to facilitate its possible overcoming in a higher phase of communism. Draper also criticizes Lenin for what he considers his confusing and contradictory usage of the notion of dictatorship of the proletariat. So, let’s return to Lenin. Lenin fully endorsed what Marx wrote to Weydemeyer (cited above) and wrote similarly that the distinctive characteristic of Marxism was the extension of the recognition of the class struggle to the recognition of the dictatorship of the proletariat.17 The aspect that Lenin was adding to the argument was about the “opportunist distortion of Marxism and its falsification in a spirit acceptable to the bourgeoisie.” So Lenin points out the new context of a new period in history, when Marxists were accusing each other of betraying Marxism and of becoming instruments of the reaction (and when workers were killing each other in the name of their nation-states during WWI): a period of acute and aggressive social malaise, when Marxism found itself to be strong enough in order to not just remain a passive observer of the pathology but an active agent within it and also, of it. It wasn’t an accident that the dictatorship of the proletariat didn’t exist in any public socialist program before this period (including the ones that Marx prepared himself). And even when they used the term for internal reasons or on theoretical works, the emphasis of the socialists of the pre-war period was on “of the proletariat” part, rather than on the “dictatorship.” The term appeared massively during WWI but initially in the program of Russian social democracy circa 1905. The First Russian revolution challenged what was considered Marxist orthodoxy and its stance towards revolutionary change.18 The newly born problem of opportunism, reformism, and revisionism in the intra-Marxist disputes was starting to become acute, together with the active appearance of the masses in the political scene. The stakes were becoming high, and also the tensions: the Menshevik Martynov, amidst the revolutionary situation of 1905, was insisting that only a bourgeois regime was in the cards. In Lenin’s hands, however, the term began to have some obscure uses as he was trying to avoid a similar path, e.g. in his formulation about a possible dictatorship of the peasantry and proletariat. It wasn’t so much the usage of the term by Lenin that was confusing and contradictory but rather the reality itself was becoming acutely contradictory and Marxism was affected accordingly, reflecting these new conditions and challenges. Several years later, in 1914-18, this tension reached a peak. Marxism was split and, while declaring fidelity to the same references to Marx, one camp of Marxists preached revolution and the other became the bastion of counter-revolution. This was the first time after 1848 that a revolution broke out in many countries in parallel and even so under the guidance of Marxists. It was during this time that Lenin offered a definition of dictatorship that is considered by Draper and others (for example by Morris Hillquit) as very problematic: Dictatorship is rule based directly upon force and unrestricted by any laws. The revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat is rule won and maintained by the use of violence by the proletariat against the bourgeoisie, rule that is unrestricted by any laws. Make no mistake, Lenin wasn’t a fanatic: during the eighth party congress, in March 1919, he stated explicitly that “it is theoretically quite conceivable that the dictatorship of the proletariat may suppress the bourgeoisie at every step without disfranchising them.” But what is disturbing to many in this passage is Lenin’s reference to non-restriction by any laws. Similarly to what Luxemburg wrote of revolution, cited before, this formulation by Lenin emphasizes the need to follow revolutionary tactics first in order to achieve democracy second. Revolutions are not static but dynamic phenomena: people realize what they want in the process of the revolution and not in advance, and revolutions help them to clarify their standpoint. Hence, the dictatorship of the proletariat will most probably appear as lawless, because there is no given legal foundation for it in advance. Revolutionary conditions do not include moments where the old legality opposes a new, fully formed one, but rather voids of legality and moments of spontaneous (even violent) acts that need to be disciplined as soon as possible through the new legality, that’s however still under formation. Bourgeois jurisprudence would surely object to what appears to it as lawless barbarism. It would be helpful, however, in this context to remember what Lukacs noted about the revolutionary, heroic, period of the bourgeois class, when it “refused to admit that a legal relationship had a valid foundation merely because it existed in fact. ‘Burn your laws and make new ones!’ Voltaire counselled; ‘Whence can new laws be obtained? From Reason!’” Moving away from its revolutionary moment the bourgeoisie gradually adopted a standpoint according to which “the content of law is something purely factual and hence not to be comprehended by the formal categories of jurisprudence.” The cohesion of laws became purely formal and the content of the legal institutions was not considered having a legal, but rather a political and economic character. In this manner, “the attempt to ground law in reason and to give it a rational content” was abandoned. The result was that the “process by which law comes into being and passes away” became “as incomprehensible to the jurist as crises had been to the political economist.” Lukacs is quoting Kelsen confessing sincerely his aporia regarding “the great mystery of law,” recognizing as symptomatic of the nature of law “that a norm may be legitimate even if its origins are iniquitous” and that “the legitimate origin of a law cannot be written into the concept of law as one of its conditions.” This blindness concerning the origin of law challenges the right of the established jurisprudence to assess the legitimacy of the proletarian revolution and its new legality. A caveat is necessary here: the recognition of the real basis for the development of law in the change in the power relations between the classes, can be misinterpreted as a repetition of the ancient concept that Thrasymachus summarized, that justice is nothing other than the advantage of the stronger. Ι cannot delve more into this problem here but Ι can certainly point out the self-conception of Marxists as certainly willing to overcome bourgeois society but only through carrying on its revolutionary tradition and completing it. In a past article, Jensen Suther and I tried to point out how “philosophy cannot be conceived as just a ‘means’ to a contingent political end Marxists happen to have — as if a set of ideologies or principles pragmatically useful for achieving ‘our’ political goals — since the ‘ends’ of Marxism themselves must be justifiable, must in principle be recognizable by all, and must meet the standards of Reason.”19 The fact that Lukacs, in his assessment of reification, included philosophy as its peak expression, shouldn’t make us forget his devotion and effort to rescue, “as a vital intellectual force for the present,” “all the seminal elements” of the thought of Hegel and the true laws of his dialectics. Unfortunately, the Russian “state of emergency” was prolonged for so long after 1917 in an isolated national regime which ended up being de facto Stalinist, and that retrospectively makes Lenin’s reference to non-restriction by any laws sound apologetic to the worst possible Machiavellianism. But we have to think: who was to blame for the failure of the revolution circa 191720 to achieve socialism on an international level, and especially to involve in the effort those countries where capital was highly concentrated? Was it because of how much Lenin’s ideas about the dictatorship of the proletariat were implemented, or because of how little they were implemented? Was the problem that we had too many Lenins or rather that we had too many Eberts? Lenin’s Marxism ultimately failed but since it went the furthest compared to all other socialisms, it is legitimate to try to correct it from within, and hence do better what Lenin tried to do instead of fully denouncing him. The bet of Marxism is to out-Lenin Lenin. The German Marxists of the SPD were repulsed by these ideas, expressed also by Luxemburg, because in premature conditions they would allegedly destroy any real prospects for socialism: but their own pseudo-prudent road for socialism, as opposed to the supposed hysteria of Luxemburg, facilitated exactly the rise of fascism and the liquidation of socialism that it wanted to avoid in the first place. Politics is indeed a dangerous business, full of risks because of the unknown outcomes. Socialist politics is not an exception. Being excited for the mass politics of the dictatorship of the proletariat, and not also remaining critical and cautious, is a problem; but being allergic to it is the biggest problem. Stemming from capitalism, any socialist wielding of power by the proletariat as a class cannot but be dictatorial. But, if successful, even with all of its shortcomings, it’s much more desirable compared to the blind irrational dictatorial reality right now.21 But how does capitalism persist in the dictatorship of the proletariat? The revolution carries with it from its direct past what Marx called “bourgeois right.” This is the right of the workers to claim for them a part of the outcome of the production process, in accordance with the labor they supplied. Bourgeois right is actually productive, in the sense that it motivates workers to engage in socialist politics in the first place: capitalism fails to fulfill the promise of bourgeois right, and not only workers do not get rewarded according to the labor they supplied, they also witness others getting rewarded more, irrespectively of their labor, with the capitalists and their families being a primary example of this unfairness. But bourgeois right is also problematic, and this is becoming apparent during the revolution. Marx explains that the equality of the bourgeois right …consists in the fact that measurement is made with an equal standard, labor. But one man is superior to another physically, or mentally, and supplies more labor in the same time, or can labor for a longer time; and labor, to serve as a measure, must be defined by its duration or intensity, otherwise it ceases to be a standard of measurement. This equal right is an unequal right for unequal labor. It recognizes no class differences, because everyone is only a worker like everyone else; but it tacitly recognizes unequal individual endowment, and thus productive capacity, as a natural privilege. It is, therefore, a right of inequality, in its content, like every right. Right, by its very nature, can consist only in the application of an equal standard; but unequal individuals (and they would not be different individuals if they were not unequal) are measurable only by an equal standard insofar as they are brought under an equal point of view, are taken from one definite side only – for instance, in the present case, are regarded only as workers and nothing more is seen in them, everything else being ignored. Further, one worker is married, another is not; one has more children than another, and so on and so forth. Thus, with an equal performance of labor, and hence an equal in the social consumption fund, one will in fact receive more than another, one will be richer than another, and so on. To avoid all these defects, right, instead of being equal, would have to be unequal. But these defects are inevitable in the first phase of communist society as it is when it has just emerged after prolonged birth pangs from capitalist society. Right can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development conditioned thereby. So, bourgeois right is inherited in the revolution from capitalism even in the optimal scenario with revolution successfully prevailing completely over the capitalists. Society on Day Two will still look forward to a kind of government that retains the monopoly of violence in order to resolve the disputes of its members, who have internalized “bourgeois right” and who are not yet accustomed to another way of life that would completely eliminate the need for a state policing the discontents produced by the unfairness of this equal standard.22 Only through creating a society in its image the proletariat can abolish itself – this is the peculiar Marxist treatment of overcoming something through fulfilling it and exhausting its potential. Some of the key manifestations of bourgeois right are already at play in capitalism: the need for the state doesn’t only reflect the competition between workers and capitalists but also the competition between workers for a limited number of jobs. When for example the cops are violently evacuating a squat, their legitimization doesn’t spring exclusively from the property rights of the owners but also, more broadly, socially and culturally, from the propertylessness of workers who are obliged to pay rent and (in an a process of identification with the aggressor) do not tolerate the “unfairness” of others not having to pay for rent also. Even more crucially, in that it remains a problem even after the revolution, when unemployment will be hopefully eliminated, bourgeois right is expressed in the injustice of equal pay for equal work between people with unequal needs: this injustice that continues through capitalism to the lower phase of socialism leads to the persistence of the need to “dictatorially” implement bourgeois right as it cannot be abolished by decrees but, according to Marx and Lenin, can only “wither away” gradually, through the political and social empowerment of the subjects that are assuming responsibility for their own pathology. Democracy is the political expression of the same problem: unequal individuals are brought under an equal point of view, and in this case they are regarded only as voters. This reasoning above is crucial in order to understand the meaning of the dictatorship of the proletariat for Marxism and the terminological preference over other options, such as democracy. Lea Ypi has also tried to explain the need for the dictatorship of the proletariat in an important article. She rightly observes that the reason Marx and Engels were insisting on calling revolutionary socialist government a dictatorship “is to remind us of the provisional and transitional nature of coercive authority or, to put it differently, to remind us of the limited legitimacy of the new political order compared with the full legitimacy that a more desirable alternative might enjoy”. She also interestingly explains how real democracy can be realized only without the state as an organized form of coercion, and that everything before achieving that is nothing but a distorted form of democracy, distorted by capital (even if capitalists are defeated).23 But she ultimately fails to grasp the subjective nature of the problem of transition to a truly free society, in her overinterpretation of Marx. She writes: Why is the legitimacy that the dictatorship of the proletariat enjoys a limited form of legitimacy? And why is it legitimacy at all? The answer, I believe, lies in an argument that Marx does not make about the epistemic impact of structural advantage and disadvantage on people’s views of justice and injustice. If the claim about the ideological effects of capitalist social relations is correct, then it is implausible to expect literally everyone in a society rigged by capitalist injustice to endorse the revolutionary project. Although, the oppressed themselves will, in the course of political struggle, acquire an epistemic insight into the scale of injustice confronted by that society, we can anticipate that their insight will not be shared by everyone. People might object to radical change for all sorts of reasons: their motives might be selfish, ignorant, immoral, or a combination of all of these. But whatever the reasons are, epistemic bias might prevent members of certain groups in society (such as those who have vested interests in the preservation of the previous order, or administrative, and political elites who are not directly oppressed and are therefore ideologically blind to the scale of injustice) from identifying with new institutions. Every institution emerging from deep political conflict faces serious obstacles in terms of the epistemic burdens associated to people’s recognition of new political roles and positions and to a new system of economic production and distribution. Thus, every institutional configuration, no matter how just in its inception, will be purely coercive for some. My counter-argument is that the institutional configuration will be coercive and dictatorial, not because of some who will deny radical change, but because of the majority that will sustain it. The dictatorship of the proletariat has less to do with a dissenting minority, and more to do with a vast majority still enchanted and dominated by the compulsion to labor as the sole (and equal) measure for value. The coercion survives in order to enforce bourgeois right, and only because of that to suppress others and oneself (to keep going to work). Immediately after the revolution, we continue to know ourselves only as workers, as commodities. That’s the pathology that still produces irrationalism that is then translated in the need for special bodies of armed workers to police and balance its problematic outcomes. It’s not as if after the revolution there is a majority fully satisfied and a minority dissatisfied; the majority remains ambivalent about the regime it sustains. The key source of coercion will not be for example the fact that some won’t want to be disciplined and go to work, but the fact that the majority knows no other way to live apart from going to work to produce value. The epiphenomenon is that they will coerce the minority but the problem lies within the majority. According to Ypi we would move to communism as soon as the minority stops the irrational resistance and adopt to the requirements of the new regime, whereas for Marx we would move to communism only if everybody changed and conquered a new way of life, beyond the regime of capital and its expression as bourgeois right that still survives subjectively after the revolution.24 The revolution that results in the political supremacy of the proletariat is a dictatorship because it doesn’t abolish capital as social domination but produces a pure form of its rule over society,25 with less distraction from the problem of its “character masks,” of capitalists who are “mere personifications of the economic relations.”26 The revolutionary potential of such conditions was thematized philosophically from Lassalle in a letter to Marx (12 December, 1851): “Hegel used to say in his old age that directly before the emergence of something qualitatively new, the old state of affairs gathers itself up into its original, purely general, essence, into its simple totality, transcending and absorbing back into itself all those marked differences and peculiarities which it evinced when it was still viable.”27 How can one radically transform the society of which one is also a part? How can one become an agent of change and at the same time be part of that which is changing? How can society be simultaneously the subject and object of revolution? It was these kinds of problems that led Marx and the Marxists to express themselves through seemingly contradictory formulations, such as that of the dictatorship of the proletariat as a precondition of democracy (and vice versa). And that’s also what led Marxists to get involved in the thankless job of party-building: multiple parties and organizations of the working class, before the revolution but even more so after it, are necessary in order to thematize politically the problem of capital, i.e. the problem of worker versus worker (and not just of worker versus capitalist), engage with it in a tangible manner and hopefully overcome it completely (proper democratic party procedures and commitment to principles become also extremely important given the problem of legality described above). Concerning democracy, we need to be careful not to turn into apologists for anti-democratic authoritarianism, but we also need to be careful not to end up in the democratic reactionary camp. Engels warned that “our sole adversary on the day of the crisis and on the day after the crisis will be the whole collective reaction which will group itself around pure democracy, and this, I think, should not be lost sight of.” This warning was issued by the same Engels who wrote that “if one thing is certain it is that our party and the working class can only come to power under the form of a democratic republic. This is even the specific form for the dictatorship of the proletariat, as the Great French Revolution has already shown.” The dictatorship of the proletariat is not undemocratic, but it is rather the outcome of how democracy undermines itself under capitalism. It’s a mistake of course to confuse and identify the democratic republic in general with the bourgeois democratic republic. But it’s also wrong to assume that even in the best-case scenario socialist democracy after the revolution will not face authoritarian challenges stemming from the economic realities still at work. The Communist Manifesto was already explicit about this: on the one hand, the revolution would allow the proletariat “to win the battle of democracy”. On the other hand, the proletariat organized as the ruling class would aim to increase total productivity of society, but “in the beginning, this cannot be effected except by means of despotic inroads on the rights of property.” Remarkably, Marx and Engels admit that these measures will “appear economically insufficient and untenable” but they clarify that these same measures “in the course of the movement, outstrip themselves, necessitate further inroads upon the old social order, and are unavoidable as a means of entirely revolutionizing the mode of production.” Instead of dismissing Marxism as confusing one should navigate through such formulations that appear to contradict each other, as Engels’ above, to try to make sense of a contradictory reality through them. The specter of dictatorship haunts us side by side with the specter of democracy because revolution is not the final victory of a communist majority of people versus a capitalist minority. The problem of capital is reproduced from below, when we, the majority, actively reproduce bourgeois right and succumb to its contradictions. An instant elimination of capitalism is impossible, it would imply eliminating all the masses of people that spontaneously sustain it (capitalism is reproduced radically differently compared to pre-capitalist societies). Hence, revolution facilitates a long challenging process of subjective also, and not only objective transformation. In this context this obscure and dense remark by Adorno starts making total sense: Marx was too harmless; he probably imagined quite naïvely that human beings are basically the same in all essentials and will remain so. It would be a good idea, therefore, to deprive them of their second nature. He was not concerned with their subjectivity; he probably didn’t look into that too closely. The idea that human beings are the products of society down to their innermost core is an idea that he would have rejected as a milieu theory. Lenin was the first person to assert this.28 This subjective aspect of social pathology, to its ultimate repercussions, is ignored by all other socialisms apart from Marxism. And this leads other socialisms into ignoring the importance of facilitating working class independent engagement with democratic mass politics, despite the pathological character of this process that Marxists of course need to remain aware of. Anti-Marxists denounce the dictatorship of the proletariat only to excuse their compromise and accommodation with the current dictatorial reality into which democracy already functions.

AuthorTeo Velissaris This article was republished from Cosmonaut. Archives December 2022

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed