|

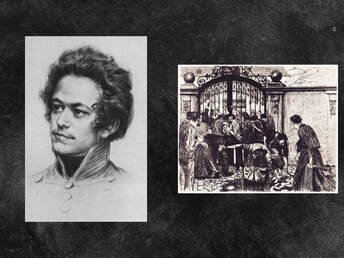

Marx and the Silesian Weavers In 1844 a group of weavers rose in Silesia, Prussia protesting the new machinery and the driving down of wages. The main action of protest was the destruction of these newly bought machines as well as the property ledgers. Afterwards, the Prussian army force was asked to come in and straighten out the situation, something which resulted in shots firing and 11 workers being killed. Uprisings like this were pretty new in this German/Prussia area, given that it was one of the last European countries to industrialize. This means that the event caught the attention of quite a few Prussian intellectuals who wrote their takes of the weaver’s revolt. One of the fellows who wrote on the uprising was Arnold Ruge, a German philosopher, and editor of the Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher. Ruge believed that this uprising had a singular character, that the revolt over these conditions were not something that could be generalized to the rest of the traditionally unpolitical Germans. This event, according to him, should cause no worry to the powers of the time, and should be considered as any other natural local distress. A curly haired 26-year-old Karl Marx responded to Ruge’s article, the essential message in the response will be a central example of how to analyze a worker’s revolt. Marx considered this uprising as what could now be called a Badiouian event. French philosopher Alain Badiou considers an event to be that instance in which the everydayness of life is destroyed and the inexistent of the current transcendence comes to light and then disappears with the finality of the event. What does this mean in layman’s terms? Well that it is in the event in which truth, that hidden inexistent of the current transcendence[1] (set of identity degrees in reality) reveals itself to people, both shattering their life as it was before, and creating the opportunity for their subjectivity. Although the truth disappears, the memory of it does not. The ethical person, the one interested in taking the path of the subject, is the one that remains loyal to the truth of the event, what Badiou calls the ethics of fidelity to the event. Essentially, this means dedicating yourself as subject to the unfolding of the truth process manifested in the event[2]. The point of bringing up Badiou’s event, is to demonstrate how, in the active participation of the unfolding of the truth process manifested in the Silesian weavers event, Marx is participating in this ethic of fidelity to truth; in this radical subjectivity which transcends the merely human with the inhuman part of the subject, dedicating itself to the service of a once hidden but now exposed truth. What then is the truth which Marx develops through his fidelity of the event? The question can be posed in the following way as well. If England had already been seeing uprisings with the Chartist, what then makes this uprising of the Silesian workers different? How does it go beyond the activity of the Chartist and the English proletariat at the time? The answer Marx gives is that: “The Silesian uprising begins precisely with what the French and English workers end, with consciousness of the nature of the proletariat. The action itself bears a stamp of superior character. Not only machines, these rivals of the workers, are destroyed, but also ledgers, the titles to property. And while all the other movements were aimed primarily only at the owner of the industrial enterprise, the visible enemy, this movement is at the same time directed against the banker, the hidden enemy.”[3] The two key points here are about the level of consciousness in the revolt. Consciousness first of itself as proletarians, which can be called the beginning of consciousness as workers for themselves, and secondly of its enemy in its visible and hidden unity. This conscious activity of a working class beginning to be conscious for itself has a historical significance. As Lukács states: “Class consciousness is identical with neither the psychological consciousness of individual members of the proletariat, nor with the mass-psychological consciousness of the proletariat as a whole; but it is, on the contrary, the becoming conscious, of the historical role of the class.”[4] This historical role is the one which calls the proletariat to “perfect itself by annihilating and transcending itself, by creating the classless society through the successful conclusion of its own class struggle.”[5] Marx saw this uprising, although de facto taking place in a locality, actually taking upon it a universal soul. In it being the natural reaction to capitalist exploitation and the different dimensions of alienation, Marx states that: “The community from which the worker is isolated by his own labor is life itself, physical and mental life, human morality, human activity, human enjoyment, human nature. Human nature is the true community of men. The disastrous isolation from this essential nature is incomparably more universal, more intolerable, more dreadful, and more contradictory, than isolation from the political community. Hence, too, the abolition of this isolation, and even a partial reaction to it, an uprising against it, is just as much more infinite as man is more infinite than the citizen, and human life more infinite than political life. Therefore, however partial the uprising of the industrial workers may be, it contains within itself a universal soul; however universal a political uprising may be, it conceals itself even in its most grandiose form a narrow-minded spirit.”[6] Although imbedded in the early philosophical phraseology of the young Marx, a phraseology he would come to drop within a couple years of writing this response, the message itself remains unchanged through his life’s work. This message centers around the importance of class struggle building itself up from the economic struggle (what he calls here the universal), towards then the political struggle (what he calls here the particular). This struggle that starts with the level of production, in the antagonisms of the present class structure, and moves from there to the political struggle, a sphere whose goal it is to maintain that class structure intact; has its first requirement for success in the achievement of proletarian self-consciousness as the historical emancipatory class. A consciousness which is itself usually achieved in the active struggle against the class determined to maintain the present order. Elaboration of the Method To understand the “universal soul” present in the Silesian weaver’s revolt, Marx had to understand, from the actions of these workers, the development of class consciousness as the result of the struggles against capitalist exploitation and alienation. With Lukács we have seen the great importance that lays in the workers achieving class consciousness; its realization represents the first necessity in any revolutionary movement. Understanding now that through the revolt itself, we can see levels of class consciousness, what else lays to be known in order to understand a worker’s revolt holistically? In this work, we will attempt to draw out the method of examination that extends beyond mere analysis of the consciousness in the rebellion. Not only to understand the totality of the revolt itself, but to also understand, more fully, the question of why a particular revolt took this form and not some other. In doing so, I hope to present a method through which the investigation of any revolt of labor against capital, could be understood in the fullness of its complexity. Before the Revolt; Quantity and Quality One of the mistakes we must refrain from, is falling into idealistic interpretations of worker revolts. One which merely looks at how we can understand class consciousness in the form of the revolt, without analyzing the material conditions that led to the revolt itself. This means that it is important to understand the material reality that is at the foundation of the conscious aspect we will examine. In the same way as in Marx’s analysis, there was before anything the awareness that the tipping point for the protest was the driving down of wages with the incorporation of new machinery. To understand this initial material level that precedes the protest itself, we must use the dialectical categories of quantity and quality. Far too often we see revolts being attributed to the last straw broken instead of understanding that ‘last straw’ as the result of a bunch of other different straws that came beforehand. For example, we know that water becomes ice at 32 degrees Fahrenheit. If we have a cup of water at 80 degrees Fahrenheit, and watch it drop all the way to 32 degrees Fahrenheit, it is that final quantitative subtraction that changes the quality of the water from liquid to solid. The same would be the case of addition and going from liquid to gas. In both instances, it takes a quantitative accumulation or subtraction to bring about a radical transformation in the thing as the type of thing it is. To often, when workers revolts is the subject of inquiry, we only look at that final degree, and forget that the degree lower is itself nothing, it is rather the accumulation/subtraction of degrees that allows that final drop of a degree (33 to 32) to go from qualitatively one thing to another, from liquid to solid, from workers going to work to workers striking. Any in depth study into workers revolts must be able to grasp this very clearly. As Brecher states “whether triggered by a relatively trivial incident or by a strike call, at some point in the accumulation of resentment workers quit.”[7] What is this if not consciousness, thanks to investigations of concrete worker revolts, of the dialectical principles that “every change is a transformation of quantity into quality.”[8] Thus, any investigation into the consciousness of workers as a historical class must understand not only the direct event that caused the revolt, but also have a general idea of the process of accumulation that gave that event the capacity of bringing about a qualitative change. Technological Rationalization and Reification of Analysis on Workers Revolt The inability to see the revolt in its full realization; seeing it as an independent thing caused by some other independent thing, constitutes the general trend of reification in a mature capitalism with universalized commodification of all things in society. What does this mean? Simply that as Lukács already noted, it is no longer just the traditional mysterious commodity that is fetishized and treated as a thing isolated from its context as the objectification of exploitative social relation, but rather this process of thingifying has extended to every other sphere of capitalist society in the course of the commodification of all things. As Lukács states: “Just as the capitalist system continuously produces and reproduces itself economically on higher and higher levels, the structure of reification progressively sinks more deeply, more fatefully and more definitively into the consciousness of man.”[9] It is of no wonder that in the general analysis of worker revolts we have a crude understanding not only of the revolt itself, but of that which caused the revolt. The revolt is rationalized with the logic of the society. Thus, what represents truly a universal character in a revolt, the worker’s disgust with the accumulation of all things in their daily exploited and alienated life; is rationalized into the logic of the system by reifying the cause of the revolt to be that final separate instance, standing alone as the sole cause of the unhappiness. In doing so, the problem is presented in a singular manner, the solution then of course is a singular one that falls within the one-dimensionality of the society. Thus, within the methodological investigation itself, we have the ideologically latent method, which presents itself as non-ideological and merely empirical, but whose actual aims are the translation of the uprisings into a logic that fits the system. As Marcuse states: “Once the personal discontent is isolated from the general unhappiness, once the universal concepts which militate against functionalization are dissolved into particular referents, the case becomes a treatable and tractable incident… Marcuse pointed how this takes place with the use of Roethlisberger and Dickson’s Management and the Worker; how they would take general statements like “the washrooms are unsanitary”, “the job is dangerous”, and “rates are too low”, and particularize it. For example, translating “the wages are too low” to “B’s earnings, due to his wife’s illness, are insufficient to meet his current obligations”; here the “universal concept of wages is replaced by B’s present earnings”[11], stripping it of its universality which aimed at a transcendence of the current system, and distorting it in its particularization to be something that can be fixed within the system. As Marcuse states: “The untranslated statement established a concrete relation between the particular case and the whole of which it is a case, and this whole includes the conditions outside the respective job, outside the respective plant, outside the respective personal situation. This whole is eliminated in the translation, and it is this operation which makes the cure (a cure within the system) possible.”[12] Thus, when we interpret a workers uprising against capital, in its full hidden material complexity; encompassing as well the finality of the universal character of the consciousness, we are not only understanding the protest itself a lot better, but also breaking through the ideological chains present in the current methodological tools of examination. Summation of Method In order to understand a worker uprising in its concrete and abstract contextuality, we must: 1-Understand that class consciousness is the first, and one of the most essential factors in a revolutionary movement. If there is to be a socialist revolution, workers must understand their position as workers in a historical manner. This means they must understand from the antagonistic relation they have with their bosses, the historical character of the current system, their bosses’ interest in maintaining it, and their own in abolishing it. 2-Be aware that in the revolt itself, the level of worker awareness of itself as the historically emancipatory class becomes visible. But its visibility in the event of the revolt is only complete if we see it in its complex, quantitative, material unfolding. 3- This means we must understand the accumulation. We must be able to not just see the last event that caused the revolt, but what came before that. What series of different events led to the point where this small, medium, or large, last event gains its status as the last event before the uprising, the final straw that broke the camels back. Simply, this means we must understand how quantity became quality in whatever revolt we examine. This method will be applied to various historical and contextual worker uprisings in further articles. [1] Alain Badiou, Second Manifesto For Philosophy (Polity Press, 2011), Ch. 4. [2] Alain Badiou, Ethics An Essay on the Understanding of Evil (Verso Books, 2012), Ch. 4. [3] Karl Marx, Critical Marginal Notes on the Article “The King of Prussia and Social Reform” Quoted from Robert C. Tucker, The Marx-Engels Reader (W. W. Norton & Company, 1978), 129. [4] Georg Lukács, History and Class Consciousness (MIT Press, 1979), 73. [5] Ibid., 80. [6] Marx, Critical Marginal Notes on the Article, 131 [7] Jeremy Brecher, Strike (South End Press, 1972), 236. [8] Frederick Engels, Dialectics of Nature (Wellred Publications, 2012), 66. [9] Lukács, History and Class Consciousness, 93. [10] Herbert Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man (Beacon Press, 1966), 111. [11] Ibid., 113. [12] Ibid., 110.

2 Comments

Clark

8/18/2020 10:28:22 am

So interesting. I consider myself far left with freedom over oneself.

Reply

Carlos L. Garrido

8/21/2020 03:48:40 pm

Hello Clark! Thank you for finding interest in the piece and for your comment.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed