|

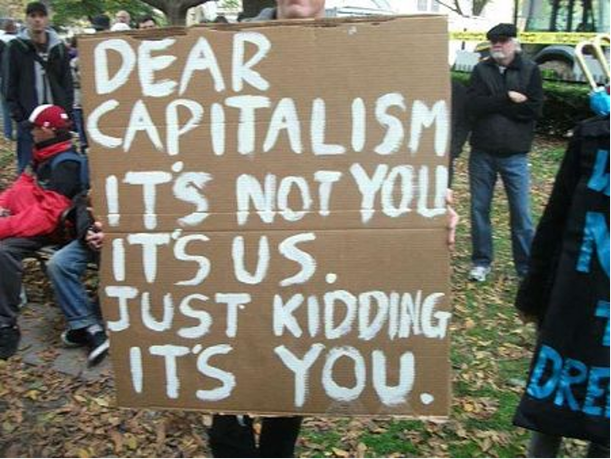

In a recent article, The New Yorker investigated what it takes for companies to ensure an output of some level of social “good” and not just profits. Beginning with the question “can companies force themselves to do good?,” the answer came from a company called Purpose Foundation: an organization that is attempting to forever change the ownership structure of corporations. The Foundation helps company owners set up what are called perpetual-purpose trusts, which become the “legal” owners of the company itself. What’s more is that these trusts are suffused with social “purposes” whether “sharing profits with workers, protecting the environment, or hiring the formerly incarcerated.” These perpetual-purpose trusts are said to last “indefinitely” and cannot be removed by new owners, thus ensuring a company’s fidelity to certain causes. The reason for creating such trusts is to alter ownership structures entirely, which, according to the Purpose Foundation's co-founder Camille Canon, is “where power is actually held.” According to the article, it's in the “dry, technocratic detail of trust law” where this power can be wielded for good over…what has really only ever been deemed as “less good.” These perpetual-purpose trusts are not without their complexity though. As the article outlines, some decisions are easier to respond to than others: “Some details could be specified precisely; the highest-paid employee, for instance, could never earn more than ten times as much as the lowest-paid employee. But other matters required flexibility and nuance. If the trust mandated that a specific percentage of each year’s profits had to be donated to nonprofits, that might limit the company’s ability to respond to unforeseen events, such as a pandemic or sudden economic downturn.” But the important work is all in finding the right, “socially conscious” investors, as was the case for Matt Kreutz, founder of Oakland-based Firebrand Artisan Breads - a company where Kreutz hires ex-convicts and even offers temporary housing to employees. Consultants from Purpose were able to get him involved with “progressive investors” that were looking to support his business along with the “socially conscious” aspects of his company, as opposed to those who saw this as excess that affected profits. Citing the 2010 Supreme Court Decision (Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission) that granted corporations the same legal protections that people had, Nick Romero makes the observation that if corporations are in fact people, “they’re psychopaths.” And this is where Purpose Foundation’s work lies: in trying to rewrite the “psychology of companies” as it were - “changing the deep structures that shape [corporations’] behavior.” The “imperative to make money” does not need to fall in line with the frenzied, capitalistic behavior of profits for profit’s sake - this “imperative…can be transformed into a requirement to do good.” A “more humane version of capitalism” is on the horizon - so the story goes. Are we saved? Is this the beginning of the end of the old, “evil” capitalism? Are we so bold to wonder “is this a step toward socialism?” Not to forestall hope, but if we are to dream socialist dreams here, the thing that’s obviously missing is any sort of politicization of these perpetual-purpose trusts. People’s World reached out to Purpose to inquire about political alignment or if there were any political projects or action committees at the Foundation. The response was a very plucky “we are doing this work one business at a time” with no political alignments or “legislation writing projects.” This appears to be a purely economic “solution” to the problem of company psychopathology. How are we to compare this to previous attempts at “capitalism with a human face” like co-founder and CEO of Whole Foods John Mackey’s “conscious capitalism” or even “philanthrocapitalism?” Conscious capitalism first began to make waves in the late 2000’s as a way to get companies to focus on “higher purposes” such as employee health and benefits, providing “equitable access” to food all over the globe, and even taking greener measures. It even seems to be garnering strength as capitalism itself has reached the “highest status of anything - above lifestyle, above health, above family, above happiness - and above humanity itself,” leaving some to argue it’s time for this system to “evolve” to take on the “unsustainable” elements of capitalism - i.e. homelessness, growing wealth disparities, and the healthcare crisis. Harvard Business Review even showed companies that practiced “conscious capitalism” performed as well as ten times better than companies that didn’t. The secret to this success? Consumers are making better, more “conscious” choices for where they buy their products and services. Not long before that, philanthrocapitalism was already in the works - an approach to philanthropy that mimics for-profit business structures requiring investors and gauges outputs of “social returns.” Although more commonly associated with Bill Gates and his Gates Foundation as well as Mark Zuckerberg today, such efforts go back to the early days of the Rockefeller Foundation and the Carnegie Corporation. Somewhere within the coordinates of philanthrocapitalism and conscious capitalism we have self-proclaimed “socialist” companies: the best example of this today being No Evil Foods. So, why do we need a more “humane capitalism?” Things seem to be moving in the direction toward progressive, socially-minded companies and consumers are responding well to it. Well, to start, we need to look at the limitations of these “good” companies. To begin with, conscious capitalism is not immune to the laws of value - or, to put it in conscious capitalist terms, the highest of the purposes is profit, or surplus value. Whole Foods was purchased by Amazon back in 2017, and the new parent company has had quite a time during this pandemic when it has come to the conditions its warehouse workers have had to survive through. Terrestrially-bored Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos has doubled his wealth during this same time period. Whole Foods has had some recent turbulence when it has come to knowing precisely which social causes are worth being the most conscious about. Recently, workers had been banned from donning Black Lives Matter slogans on masks and shirts. During November of last year, three Trans employees filed official complaints of transphobia due to harassment - two of which were eventually let go from their respective stores. Whole Foods also removed health benefits for part-time workers and limited hazard pay during the height of the pandemic. Not to mention the paid time-off system where employees can donate PTO to other employees if they are in need of it, rather than the company itself giving out more paid time-off to employees in need or not. Employees are not required to donate, but the moral impetus is clearly put upon co-workers rather than management. Workers rights, Black lives, and trans dignity don’t appear to top the list of “what conscious capitalists care about,” and although John Mackey is quick to point out that Whole Foods was the first to ensure proper sterilizing measures and COVID protocols, he is withholding purposeful action on several other social issues. “I like to keep my political beliefs, beliefs about controversial issues, to myself. I don’t really want to talk about racism. I don’t want to talk about climate change. I don’t want to talk about riots or fires. I want to talk about conscious leadership,” said Mackey during an interview with Isaac Chotiner of The New Yorker. “I’m opposed to racism. That’s my position on racism. End of discussion.” Being purpose-driven with capitalism appears to succumb to the same whims of majority owners, board members, and C-level executives as “regular” capitalism - or, Capitalism Classic. Perhaps philanthrocapitalism is having less of a rocky start to winning over the people. In their recent book Inflamed, Rupa Marya and Raj Patel give a brief historical breakdown of philanthrocapitalism. The Carnegie Corporation, one of the first modern philanthropic organizations to exist, had directly “alter[ed] the course of US medical education and practice,” having helped close five of the seven Black medical schools in the United States at the time; and also was involved in the promotion of “global whiteness,” as political theorist Tiffany Willoughby-Herard put it, for supporting the Afrikaner white nationalism of South Africa. Citing both the Rockefeller Foundation and the Gates Foundation, these “philanthropists” tend to disappear Indigenous knowledge and practices (specifically when it comes to medicine) while purchasing land in which to mine for resources. Gates himself owns 242,000 acres of arable land, some of which he’s using for nuclear power, “making him the largest farmland owner and occupant of stolen territory in the United States.” Pointing out that “[p]hilanthropists traditionally use their money to project their visions onto foreign places,” Marya and Patel conclude that “[p]hilanthrocapitalism is the latest in a long series of technologies for the social reproduction of colonial power.” What about companies that are manufacturing products that are better for the environment and healthier for us? Well, No Evil Foods started their 2021 with union busting and ended with laying off 30 to 50 production workers without severance and canceling their benefits. To no one’s surprise, these efforts were financially motivated and were necessary so that they could, as co-founder Mike Woliansky put it, “save animals and help people be healthier or help save the planet.” These examples of course in no way discredit an entire systematic approach to private ownership of the means of production, even if it is allegedly socially conscious. However, we are left to wonder what is a good company? On the inside, many of us have worked places where we were assured we were a family only to find that this “familial connection” was meant to elicit more time and effort from us, produce guilt for not doing enough or off-loading responsibility onto co-workers, and provide a sense of belonging so employees think how they are treated is “ok.” Asking more of employees has been the method of any and every job or boss, but the “family” functions precisely without having to ask: employees tend to police themselves in this way hoping against hope that if/when layoffs happen, if/when the next pandemic hits, if/when benefits must be cut, they will be spared. This is what conscious capitalism looks like from this side of the looking glass. What about from “outside” a company: what does a “good” company look like from that view? It would appear that this is a much more complex question to answer. After all, does not this view of a company doing good depend fully on the company’s image itself? Where does that leave the actual practices of the business? Any person on the street can celebrate a company like Ford Motor for building a plant dedicated to manufacturing zero-emission pickup trucks while ignoring what this could do to the area’s drinking water and what Ford has a known history of doing in other cities (where many of their employees tend to live) - Flat Rock and Livonia, Michigan both have endured recent toxic chemical spills. In such cases, it would seem we are left to choose between a company’s image and a company’s actions. If a company’s actions are more consequential to our lives, why do we keep coming back to the image? Is this not the precise lesson of Hannah Arendt’s famous concept “the banality of evil?” Rather than simply being “clueless” or unaware of the actions and consequences of a company - who they are exploiting elsewhere, what harm they are causing to the environment, what crimes they are committing - aren’t we fully aware and purposefully ignoring it? Do we not give corporations free passes like this all the time? Chik-fil-A’s recent commercials about how they treat their workers (who we are assured “enjoy” going above and beyond) may make us feel good but has anyone truly forgotten their anti-LGBTQIA+ history? Or is it easier to disavow such histories as simply that: dead and history? Perhaps it's easier to pull into the nearest gas station without considering if one is ready to forgive Shell or BP for their atrocities. It’s here that we must return to the “companies as psychopaths” argument and make a slight change: if companies are psychopaths, us as consumers and employees are sociopaths. But this seems to put a lot of credit into the hands of the consumer/employee. Is ignoring a company’s wrong-doings all our fault or are these companies banking on a “sociopathic” acceptance of their image? First, it’s important to interrogate what the “psychology” of a company means. If a company is a psychopath, then we’re left to conclude that those in the driver’s seat - the CEO, owners, board members - make up the “psychology” we are concerned about here. Second, we need to remember that a company’s “psychology” is all too real today as social media roles proliferate across industries: these being jobs where employees are to act as the “face” and are directly responsible for embodying a company’s so-called values and “speak” its words, as it were. Indulging this psychology both reifies the idea of employee responsibility to ensure a company’s morals and further distances the responsibility of these “psychopathic” tendencies from those actually acting on them. Vegan business magazine, the Vegconomist makes the point even clearer here: “entrepreneurs are just everyday people trying to accomplish big dreams, sometimes unrealistically big dreams. If successful, they create great products, lots of jobs, and consumer and investor value. But it isn’t always a straight line to the top. It is often one step up and two steps back, to then hopefully jump three steps up.” The formula is a little more direct: if companies are psychopaths, it’s because of those who have big dreams of value. Another way to word this is value is both the goal and the driver or in Marx’s formula of capital: money begets product which begets (more) money. Although capital itself has changed - most billionaires tend to have very little actual money in their bank accounts - the goal of (surplus) value through profits has remained. How do perpetual-trusts help us out of this deadlock? Is its fate any different than capitalism in all its flavors? The obvious reaction here is that it’s better to give anything at all to a cause or charity than to give nothing. Indeed, this is true, but what is “humane” and what is “marketable as humane” are becoming indiscernible. Capitalism’s most distinguishing characteristic is its ability to self-revolutionize: what makes it so remarkable is its ability to subsume new forms of relations of production without hitting the limits of those relations. In short, capitalism constantly changes its own conditions of existence and this is where its true power resides. Humanitarian capitalism thus finds its contradiction-to-overcome in the very nature of a perpetual trust: the legal “indefiniteness” of such a trust would be an obstacle to this constant revolutionizing. This leaves these trusts and the companies themselves vulnerable to the threat of economic impact from extensive litigation, either as a way of forcing negotiations or sidelining a competitor. But is this a step toward socialism? No. This seems more like a step to ensure that socialism in fact never comes about. We need only to look at some of Purpose Foundation’s other work to understand the difference between this flavor of capitalism and socialism: the Trust Neighborhood is an effort to ensure clean, safe, and affordable neighborhoods that are also “mixed-income.” This is an interesting euphemism for different classes “coexisting” in the same neighborhood. We’re already aware of the links between class disparities in the same communities and suicide, but this seems to ignore the class aspect as being problematic. This is an effort not to abolish class antagonisms, but, as Slavoj Žižek recently pointed out, to ensure one’s class-identity is respected and remains intact. If we are to take humanitarian capitalism seriously, we must first acknowledge that humanitarian capitalism doesn’t take its own (class) antagonisms seriously enough. The problem with this, above all else, is that it’s a de-politicized attempt at change. The fact that so much of where the “power is actually held” has to do with legalities - from perpetual-trusts, ownership power structures, and Trust Neighborhoods - shows the power the law and state have in economics. To put this more aptly, it is the sphere of economics that is subordinated to the political terrain. Social “good” cannot come from economics alone. Perpetual-purpose trusts or not, the direction of a company’s purpose is determined first by the whims of an owner, executive, or majority shareholder. What’s more is that the legalities of these trusts are subjected to “politics as usual” - a social status quo which we already know all too well. To sum up “humanitarian capitalism,” it seems we’re looking to change everything in order that it all remains the same. AuthorAndrew Wright is an essayist and activist based out of Detroit. He has written and presented on topics such as suicide and mental health, class struggle, gender studies, politics, ideology, and philosophy. Archives January 2022

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed