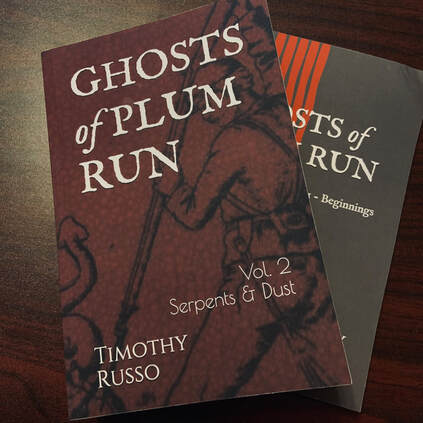

Jane & The General - Antebellum Cancel Culture; Excerpt from Ghosts of Plum Run Vol. 2 ~ Serpents & Dust Sylvanus Lowry, by age 34, was the most powerful man in central Minnesota in 1858. His father was a Kentucky preacher slaveholder, who circumstance placed as a missionary among the Winnebago tribes in Iowa. Thus, as a child, Sylvanus Lowry gained many advantages; a good education, rudimentary Winnebago language skills, inherited wealth built on stolen labor, and connections to every one of the western territories’ power brokers, including U.S. Congressmen. Lowry used these to place himself astride the Red River Trail at age 23 in 1847, with his slaves, where St. Cloud popped out of the prairie at a Mississippi River crossing 65 miles north of St. Paul. Fur trading mixed with the connections to power to give Lowry a fortune, which he used to purchase the northern third of St. Cloud’s land, move his father and sister to town, and become one of the most influential Democratic Party politicians in pre-statehood Minnesota, even becoming St. Cloud’s first mayor. A majestic, refined, dignified, born to command handsome devil, he was known as ‘General’ Lowry because his connections and power landed him as the territorial adjutant general on top of it all. Slavery west of the Mississippi was a very open question when Lowry arrived in Minnesota in 1847, soon to explode into bloodshed in Missouri and Kansas. By 1858, General Lowry’s powerful position made slaveholders feel very welcome in Minnesota, even safe, safe enough to dream of riches built on unpaid forced labor on land whose value never seemed to decline. Lowry intended to be at the top of that heap should Divine Providence smile upon his luck, a bet placed by not a few other slaveholding southerners who settled in St. Cloud thinking just the same thing. They invested in the various land schemes, vacationed their summers away in Minnesota, bringing their slaves with them up the river. One such slave was named Dred Scott, whose army officer owner kept Scott for a time at Fort Snelling near St. Paul. The March, 1857 Supreme Court decision denying Dred Scott freedom gave one last, slave value induced pump to the land bubble before it burst in the Panic of 1857. General Lowry himself was an investor in the bubbly boondoggle Nininger, pulling every string he could, which were many, to get Nininger a city charter or a steamboat stop or special treatment in the territorial legislature, whatever his power could do. The entire winter after the Panic of 1857, Lowry accelerated the sales job, leaving no stone unturned in the local press across Minnesota to convince the world nothing was amiss in Nininger at all. Nothing was amiss anywhere! Shameless boosterism filled the papers of Minnesota to prop up what had already gone poof. Into this media haze hovering over economic collapse on the frontier, a woman on a mission turned up. Jane Grey Swisshelm was born Jane Grey Cannon in 1815 near Pittsburgh, raised a Presbyterian Covenanter who observed the Sabbath, the Good Book, all of it with the strictest of reverence. She was reading the New Testament by age 3. Little Jane was so smart her mother negotiated her into teaching her fellow students at boarding school by age 12 when money ran out for boarding and tuition. Tiny, pretty, artistic, able to paint portraits, recite poetry, and fiercely independent, marriage at 21 in 1836 tore it all down for Jane, bit by bit, year by year. Her eyes were opened by slavery’s resemblance to her own predicament as a woman; she felt owned, because the law said so. Her Methodist husband James Swisshelm demanded total obedience and subservience, citing scripture of course, which was Jane’s weakness. She bought the whole thing, hook, line, and sinker. She let him coop her up in her own mother’s house, only visiting twice a week, like she was a pet horse in a stable. She let him force her to do only his work, denied her any work that fit her precocious talents, dragging her to Kentucky in 1838 so she could knit dresses that he sold for his brother. It was in Kentucky Jane met slavery face to face, seeing men father children with women they owned as slaves, children who their own fathers then sold for profit, over and over, like siring their own cattle. She heard the cries and screams of slaves whipped into submission in public, sounds her own heart could summon, if she ever dared let it come out. When her husband refused to allow Jane to visit her mother at her death bed, the cries began to find voice; Jane went to Pittsburgh anyway to nurse her. After her mother died, Jane learned Pennsylvania law allowed her husband title, from her own dead mother’s estate, to “wages” for the time Jane spent nursing her dying mother, selling even the tiniest memento for money, for him. So, Jane Grey Swisshelm’s voice began to ring out. “Gentlemen, these are your laws!” Jane wrote in a letter to the Pittsburgh Commercial Journal in 1847. Within a year, those laws were gone, Jane’s first writings giving crucial support to the tireless work of many Pennsylvania women before her. The power of the pen and press, so intoxicating when it produces instant impact, filled Jane with self worth, self actualization, self esteem, like a boiling volcano up from the ground to her feet, through her body, into her veins, out to her fingertips, into the quill of a pen dipped into an ink well, then onto paper, wielded at will. It became Jane’s new obsession, and her target became slavery. In slavery, she saw herself and her marriage. Her husband James was an abolitionist too, but neither clever nor wise enough to see her abolitionism as a channel for her rebellion against him. Jane Grey Swisshelm intended to force that realization, if not on her husband then upon the world, with words in print, launching her own newspaper the Pittsburgh Saturday Visiter in 1848, the same year Peter Marks left his Prussian aristocratic family to revolt in another way. “There is no room in this broad land for both me and General Lowry,” Jane Grey Swisshelm told her sister in 1857 when she moved to St. Cloud with her 6 year old daughter, leaving her husband behind in Pittsburgh finally, growing ill, older, and exhausted. Filled with the self confidence publicly seen victory in ink gave her, Jane’s intent was to live the quiet life of a pioneer woman with her little girl, her sister and brother in law on 40 acres near a lake. But by now, Jane was so well known for her abolitionist writings that a group of backers approached her on the last leg of her journey west, the 65 miles between St. Paul and St. Cloud, to brief her on General Lowry. They knew full well that once Jane learned a slaveholder lorded over the land she intended to retire upon, the fire would be lit. And what a fire. The weekly St. Cloud Visiter was born nearly as soon as Jane set foot in St. Cloud. Sensing the threat, General Lowry immediately offered to subsidize the new paper if Jane, as editor, endorsed and supported President James Buchanan, which she accepted - as a running joke. Jane’s rapier pen slashed away as Buchanan’s “only honest supporter...the sole object of his administration being the perpetuation and expansion of slavery,” whose Democratic Party territorial government Jane “celebrated” as existing entirely to expand slavery to Minnesota and every inch of land west of the Mississippi. Huzzah! Within months of its first edition, open war raged between General Lowry and Jane Swisshelm in St. Cloud’s press. Jane’s biting ironic vitriol blossomed, praising General Lowry for living, as any Buchanan Democrat should, in “semi-barbaric splendor” towering above the riverbank in St. Cloud. Jane was such an instant sensation in central Minnesota, Lowry even launched his own newspaper, The Union, to punch back at the meddlesome woman who knew not her place. It all came to a head in March, 1858. One of Lowry’s lackeys, his lawyer named James Shepley, gave a public lecture On Woman, particularly those needing to learn their place, a feeble attempt to silence the uppity editor. Jane responded in the Visiter by reminding Mr. Shepley he’d forgotten in his lecture a certain sort of woman needing to learn her place, a gambling woman, and all understood Jane described Shepley’s own wife. In print. Mrs. Shepley was apparently a “large, thick-skinned, coarse, sensual featured, loud-mouthed double fisted dame...who talks with an energy which makes the saliva fly like showers of melted pearls” whose “triumphs consist in card table successes, displays of cheap finery, and in catching marriageable husbands for herself and her poor relations”. This, of course, was the last straw. The night in March, 1858, after James Shepley's wife's reputation was soiled by Jane Grey Swisshelm's newspaper, Shepley and his accomplice, Dr. Benjamin Palmer, his divorced sister-in-law’s fiancé, broke into the St. Cloud Visiter's building, hoisted the printing press and typesetting between them, then raced to the Mississippi River to dump it. Triumph was swift for Jane Grey Swisshelm that night after the break in, at a rally at which she spoke in public for the first time in her life. Jane named the perpetrators to the hundreds gathered. Then, Jane announced an apology to Mrs. Shepley, to protect her paper’s backers from libel suits, and announced a new paper would be launched which she solely owned, if only support could be gathered in the community to buy a new printing press in Chicago. The crowd bellowed support in roars and applause. Thousands of dollars were raised for what would become the St. Cloud Democrat overnight. Thus began the rapid decline of General Lowry. National press covered Shepley’s break in, heaping scorn from every corner of America, against which Lowry’s mouthpiece local weeklies were utterly impotent. He became a laughing stock. A year later, Lowry lost his first election in 1859, for lieutenant governor. The last election Lowry won was for Minnesota State Senate in November, 1861, at the beginning of the war, as a Democrat who wanted to preserve the Union as it was, with slavery, the whole point of his entire life’s existence. Then, like poetry, Nininger, the gift that never stopped giving, engulfed Lowry in madness. Property disputes of byzantine complexity descended Lowry into a blackness, bouncing across hospitals for the insane in Ohio and Iowa from the start of his term. Jane Grey Swisshelm took one last stab at General Lowry on his way down in May, 1862, reporting in the St. Cloud Democrat the state senator’s “attack of mental aberration... principally induced by hereditary taint”. She maintained the irony she used to vanquish him, feigning sympathy in dripping sarcasm to report “in lucid moments he talks distressingly of his past life as a series of mistakes.” By September, 1862, Minnesota Democrats decided Lowry had gone quite round the bend, well past his usefulness, so replaced Lowry in the state Senate only nine months into the term. Cast adrift, gone mad, Lowry lived only three years more, lost in his own mind, whatever was left of it, arrested in 1864 for threatening his own sister with a pistol. On December 21, 1865, at the age of 42, General Lowry died. No one knew how. Rumors briefly held that abolition achieved after the Civil War, Lowry’s fevered mind decided it might as well be over his dead body, so he blew his own head off with a shotgun. Mostly, he just faded away. Ever on the hunt for more crusades, Jane Grey Swisshelm next aimed her fire at the Dakotas, in response to their 1862 revolt in Minnesota which had to be put down with troops sent home from fighting the Confederacy. Her understanding of profit motivating oppression, even her own, did not extend to the tribes still living on land stolen from them, and wanting to keep it. Swisshelm’s hatred toward native tribes after the Dakota War ran so hot, she took to the lecture circuit to advocate reprisals more vicious than she had ever hoped to descend upon General Lowry. The Dakota War ended with the largest mass execution in U.S. history, 38 Dakotas hanged in Mankato on the day after Christmas, 1862. Swisshelm’s lecture tour took her to Washington, DC, where she worked as a nurse to wounded troops in Union hospitals. She landed a federal job in the Lincoln administration, and sold her newspaper in Minnesota, starting a new paper to attack the Johnson administration over reconstruction, which lost her the federal job, and the paper. Her last activism was to attend as a delegate the 1872 Prohibition Party convention, trying to ban the sale and consumption of alcohol. She finally returned to Pittsburgh, where she died in 1884 at 69 years old. AuthorTim Russo is author of Ghosts of Plum Run, an ongoing historical fiction series about the charge of the First Minnesota at Gettysburg. Tim's career as an attorney and international relations professional took him to two years living in the former soviet republics, work in Eastern Europe, the West Bank & Gaza, and with the British Labour Party. Tim has had a role in nearly every election cycle in Ohio since 1988, including Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020. Tim ran for local office in Cleveland twice, earned his 1993 JD from Case Western Reserve University, and a 2017 masters in international relations from Cleveland State University where he earned his undergraduate degree in political science in 1989. Currently interested in the intersection between Gramscian cultural hegemony and Gandhian nonviolence, Tim is a lifelong Clevelander. Purchase The Ghost of Plum Run Vol. 2 HERE

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed