|

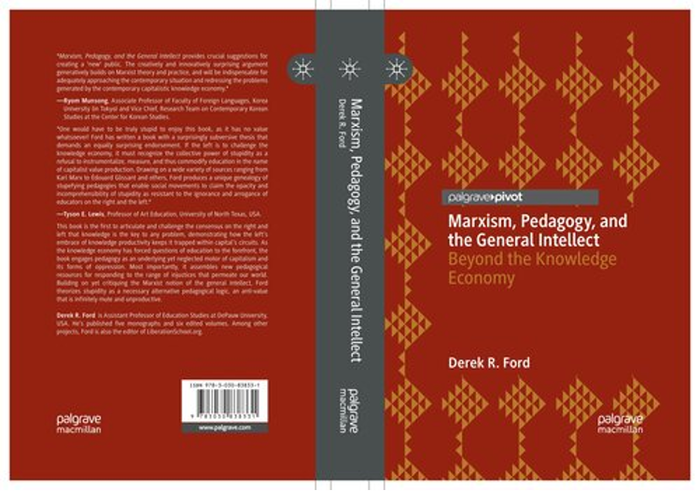

11/11/2021 The Best of All Possible Pedagogies: Derek Ford’s Anti-Capitalism and Anti-Pedagogy. By: Calla WinchellRead NowIf we are meant to imagine new worlds to come, as anyone who believes a better one is possible does, it follows that the new cannot be achieved with the same tools which made the old world. Just as we seek to disengage with the more obvious structures of capital, so must we depart from a pedagogy that mechanizes and moderates learning in service of valorization. In his new book, Derek Ford offers a sharp account of the current knowledge economy. First offering a history of its development, then an analysis of its structures, Ford incisively critiques both the right and the left for the pedagogical orientation they’ve adopted. While offering significantly more criticism for the right, his analysis of the left as inadvertently adopting a value of learning only for productive purpose is remarkably incisive, a form of learning solely as a means to generate profit or generate value for collective development. However, his account falls short in the final movement of the text, where he offers his diagnosis for the problems he deftly describes. Ford proposes, as an alternative to this knowledge-above-all-else orientation: stupidity. There is some vague gesturing towards a sort of theoretical understanding of stupidity, where it resists definition and organizes without thought. Much of that account is also interesting, the ways the stupidity allows marginalized groups to deny the legitimacy of the orthodox pedagogy they live under. Still, the fundamental mistake he makes is that Ford too seems to lose perspective of pedagogy. It seems he can only see learning as innately tied to capitalist production. So he rejects learning as such for an anti-pedagogy, that of stupidity. In doing so, he mistakes current pedagogy for all pedagogy, and argues for a total rejection of such form, despite the ahistoric nature of learning. To begin, Ford defines the changes which took place in the post-Fordist era, moving from industrial capitalism to cognitive capitalism’s knowledge economy. The name refers to a new privileging of knowledge production, in contrast to more literal production, like manufacturing, which was declining among previously industrial countries in the post-war years. As Ford states, “the claim is rather that the role and status of knowledge—including the conditions and results of its production, distribution, and utilization—have increasingly taken on a determinant function in economic, social, and political development” (Ford 2). In other words, in a knowledge economy, profit was no longer primarily being produced in the factory, but the university, in the R&D lab, or the think tank (notably, even if such organizations receive public funding their innovations will likely find their way to private corporation’s control). “What matters above all else,” in cognitive capitalism, “is that knowledge and learning are measured or measurable,” (59). As a result of this shift, a valid pursuit of knowledge is one linked exclusively to that knowledge’s potential productive capability. This is not knowledge for its own sake but for the sake of the shareholder. For Ford, “the primary problem turns on the private ownership and enclosure of knowledge and the goal is an elimination of both” (28). The resulting system, which is one of competition, is inefficient even in its stated goal to generate economically valuable knowledge. The current capitalist framework is one that encourages the binary of professional/amateur, expert/ignorant, and so forth. This limits who may participate still further. But a problem arises: despite how useful the knowledge economy has proven for capital, knowledge has an inherently destabilizing effect that opens up new possibility, due to: “the collective, nonrivalrous, easily duplicated, and immaterial nature of knowledge—as well as the collaboration and openness required for knowledge production— [which] makes it unwieldy for capital,” (31). And so, Ford moves on from discussing the right’s knowledge economy and turns towards its opposition. In contrast with the primacy of the patent in the existent knowledge economy, Marxists value what Ford terms, “the commons”, particularly the notion that “knowledge production relies on common knowledge to cooperatively produce new knowledge” (30). And an environment of access and openness in a knowledge economy of the commons has obvious benefits. Is innovation encouraged by collaboration or secretive competition? Are paywalls good for the general education of the public? Ford observes the great inefficiency of a profit motivated system: “they redefine research and knowledge production in the service of capital accumulation, or, in the words of the development agencies, in the numbers of citations and patents they produce.” But is an economy of the commons possible? Ford suggests they are, even under existing material conditions, using projects like Wikipedia and the movement for Open Education Resources (OERs) to show the potential of collective intellectual organizations (33). Note that the distinction between professional/amateur or expert/amateur dissolves under these frameworks. Your Wikipedia contribution doesn’t require you to have a doctorate in the subject, just a proper citation. So, when information is commonly held and anti-hierarchical, knowledge production accelerates; thousands of minds are better than ten expert ones, no? Yet there is an issue that arises. Ford makes his sympathy with Marxists evident because they’re receptive to less overtly profit motivated pedagogy. “The marxists want to win this struggle because they recognize the centrality of knowledge as an expression… of an immanent alternative world emerging in the present one,” Ford argues (3). Despite that wider openness to learning, Marxists have inadvertently absorbed that same tendency to admire knowledge for its utility. Though profit motive may not be directly present, the same mindset which treats knowledge as a commodity remains. In his view, “both [left and right] view knowledge as a raw material, means of production, product, and subject that is created, distributed, and consumed in a ceaseless demand to produce…” (Ford 9). Treating knowledge as a commodity makes little sense, not least because “knowledge doesn’t obey the same laws of scarcity or rivalry as physical commodities” (26). There is no limit to how many times a book may be read or an algorithm shared. Even this, however, misses the wider problem, which is that every side of the political spectrum believes, “that the knowledge economy is significant because knowledge is a productive force” (emphasis mine, 63). Specifically, the problem is that each side believes development of knowledge to be “an undeniable good” (65). This is a mistake, for it perpetuates “circuits of capitalist production” and “reinforces the systems of oppression and domination” that Marxists want rid of (Ibid.). What does Ford propose as an antidote? He offers a theoretical form of resistance: stupidity. His positioning of stupidity can feel disorienting and vague; Ford acknowledges this but attributes that to the ineffable, elusive nature of resistant stupidity. Discussions of this kind, about abstract concepts and envisioned worlds-to-come will, by their very nature, bump into the limits of language, brush up against the edge of syntax. Much of Ford’s prescriptive section of the text exists in this realm. Many generative thoughts are here, and yet, I was left wondering if there wasn’t a better, more accurate word he could use. Language will always struggle to contain theory like this, but you must use the words that get you closest to that which is beyond description; it feels as if the concept’s relationship to the label of the stupid is imperfect and that makes any conclusion hard to reach. “Stupid” as a term is already laden with meaning and so, without more clear description of stupidity as something to pursue, I found myself working off the popular waning of the term. If that is the case, why pursue it, why not clarify the phrase until it can be parsed accurately? Because it doesn’t fit with the normal definition of stupidity — but rather a kind of inverting of the hyper-knowledge present — so much of the description of this anti-pedagogy/pro-stupidity argument relies on negations of the current state instead. “Stupidity is not the opposite of knowledge, nor is it its absence or lack. Defining stupidity is, by its very nature, impossible (76). Note how this “impossible” definition is told in negation, in absence; by telling us what it is not we are meant to understand what it is. Ford even notes his concept’s definition via negation, calling it “an anti-value” (82). His more developed version still relies on antithesis, but with little gesture towards a praxis of stupidity: Because stupidity can’t be educated, its unknowabilty, opacity, and muteness endure beyond measure by remaining inarticulable and incommunicable. No databanks can store stupidity, no technologies can quantify it, and no technologies can discern or articulate it (emphasis mine, 83) Still, despite stupidity's sketchy nature, Ford argues it is necessary to pursue, as it provides “an alternative pedagogical motor for an exodus beyond” our current era (79). Ford qualifies these claims, writing that this wasn’t “an uncritical celebration of stupidity and a rejection of knowledge or knowledge production,” and yet that is how it can be read (15). There is no coexistence of revolutionary stupidity and pursuits of knowledge for the commons (which replicates capital logics and are thus tainted). And, more practically, what would adopting this anti-pedagogy look like? With a definition that primarily rests on negation and inversion there’s not much direction about how to develop stupidity. Ford writes, “stupidity is not a refusal of production but an inability to produce” (original emphasis, 82). How can you cultivate an inability? Even if the reader entirely accepts Ford’s solution, I did not conclude with a sense of how it would actually work, or what organized stupidity-as-resistance might look like. It is also not clear why the very idea of pedagogy has been so sullied by capital as to demand its total rejection and an embrace of its antithesis. While Ford’s description of the left and right’s shared problem — thinking of knowledge as a commodity to be produced — is entirely accurate, he appears to make the same mistake those he critiques make: he cannot peer out of the superstructure and is blinded by current conditions. Ford has mistaken the specific conditions he lives in, which are objectionable, for something problematic about the nature of pedagogy itself; thus, his solution is the complete rejection of learning. That is quite an extreme position to take. If pedagogy has changed as eras changed (and it has) what makes the current position so inescapable? Pedagogy no doubt has changed as society has transformed, so why does this particular set of material conditions demand adopting an “anti-value”, instead of an adjustment? This is a mistake that Marxists need to be cautious of generally: mistaking the historically produced, material conditions we live in with an eternal state of being. While he is correct that the pedagogy adopted on the left can reproduce a similar emphasis on productivity as the ultimate good, he seemingly forgets that capital (and its accompanying logics) has existed for some few centuries, where learning has been an innate part of humanity since it has existed. Personally, I’d rather attempt to get away from this relatively new pedagogy of cognitive capitalism, change material conditions, and develop something different, rather than invert pedagogy and seek out stupidity as a form of resistance. There are many strengths in the text which deserve comment: Ford deftly intertwines disability justice with anti-capitalism in an intuitive way, his analysis of the history of the knowledge economy is concise and informative, and his diagnosis of the problem on both left and right side feel very cogent. In a world where no one understands the zeitgeist, where the absurd becomes the real everyday, it is difficult to fault such a careful academic because he doesn’t have a fully developed answer to address the problems of the knowledge economy. Ford’s analysis is clear and serves as a strong introduction to understanding cognitive capitalism. It also offers fair critiques of right and left pedagogical practices. That he gestures vaguely for another way that remains undeveloped is a frustration but no reason to reject the text writ large. Hopefully, Ford will continue to develop this anti-value as a concept; I’m interested to see where else it might take him. Whether we pursue the commons and proletarian general intellect or embrace stupidity, a better world is possible and can be built on the backs of new pedagogical orientations. AuthorCalla Winchell is trained as a writer, researcher and a reader having earned a BA in English from Johns Hopkins University and her Masters of Humanities from the University of Chicago. She currently lives in Denver on Arapahoe land. She is a committed Marxist with a deep interest in disability and racial justice, philosophy, literature and art. To read Derek Ford's book click here. Archives November 2021

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed