|

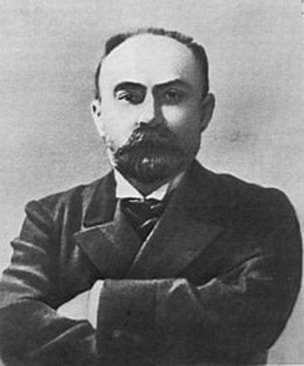

Next year marks the 120th anniversary of the Second Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party. This was the famous Congress where the split between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks took place. Lenin’s ideas, of course, won out at this Congress, and he was supported by a man who was considered the “Father of Russian Marxism” and the founder of the first Russian Marxist group, The Liberation of Labor (1883). This was Georgii Valentinovich Plekhanov. Although Plekhanov later switched to the Mensheviks, Lenin still found him to be an ally on many issues — at least until 1914 when, like so many others, he ended up supporting the war. The passionate politics of those years now adorn the pages of history books and live on in the unending debates and fulminations of the ultra-left “Marxist” sects which dot the university campuses of Western Europe and the United States. We have little interest in Plekhanov as a political leader today, but his theoretical grasp of Marxism as a philosophy of liberation is practically unequaled. Along with Marx, Engels and Lenin, Plekhanov stands as one of the greatest teachers of Marxist theory produced by the working class movement. The term often used to characterize Marxism as a philosophy -- Dialectical Materialism — was first used by Plekhanov in 1891(it was coined earlier, however, by Joseph Dietzgen,1828-1888) . And Lenin said of his works: “You cannot hope to become a real, intelligent Communist without making a study — of all of Plekhanov’s philosophical writings because nothing better has been written on Marxism anywhere in the world.” Well over a century later this judgment can still stand. Plekhanov’s works stand, along with the great classics of Marx and Engels, as some of the clearest, most popular, and easiest to read introductions to the philosophy of human liberation. Some of Plekhanov’s most accessible works are Essays in theHistory of Materialism, The Monist View of History, Fundamental Problems of Marxism, The Materialist Conception of History, Art and Social Life and the essays “The Role of the Individual in History”and “For the Sixtieth Anniversary of Hegel’s Death.” The Hegel article is short and an excellent introduction. Here are a few of Plekhanov’s formulations of Marxism that have become well known even if their origins in his works have not. He wrote, “the appearance of Marx’s materialist philosophy was a genuine revolution, the greatest revolution in the history of human thought.” This shows great party spirit, but Darwinists might want to claim at least equal status (not to mention Copernicus). Marxism is a unified worldview. Can we graft other notions onto it, or drop parts we dislike? Can we have “Christian Marxism” or “Existential Marxism” and so forth? Plekhanov thinks not. There are no “best” and “worse” ideas of Marxism. He maintained “all aspects of the Marxist worldview are linked together in the closest way … and therefore one cannot arbitrarily eliminate one of them and replace it with a set of ideas equally arbitrary drawn from a completely different worldview.” Plekhanov also characterizes Marxist dialectics as the “algebra of revolution” and held that “dialectical materialism is a philosophy of action.” This became the basis of the notion of “the unity of theory and practice” in later Marxist thought. “After all,” Plekhanov wrote, “without revolutionary theory there is no revolutionary movement in the true sense of the word …. An idea that is revolutionary in its internal content is a kind of dynamite for which no other kind of explosive in the world can be substituted.” Among the many contributions to Marxist theory made by Plekhanov was an application of Marxism to a theory of art. Neither Marx nor Engels ever devised a theory of art. Nevertheless it is possible to deduce an art theory from the scattered references to art and comments about art and society found throughout their works. Three of Plekhanov’s works are especially important in this regard: Fundamental Problems of Marxism, Art and Social Life and his essay “The Role of the Individual in History.” Plekhanov sees nothing individualistic in the origin of art. Art arises from the historical development of a people or nation. In class-based societies no school or trend of art can become popular or be successful without representing the interests of some class or stratum of society. Plekhanov writes: “The depth of any given trend in literature or art is determined by its importance for the class or stratum whose tastes it expresses, and by the social role of this class or stratum…. in the final analysis everything depends upon the course of development and the relations of social forces.” It is Plekhanov’s view that art is part of the superstructure of society that is reared upon the social base, namely the mode of production. The production mode gives rise to the production relations which in capitalism lead to two great classes, the owners and the workers, and the history of the society is propelled along by the struggle between them. This struggle, in turn, gives rise to social antagonisms, contradictions, alienation and a host of vexing and unsettling events that disrupt the smooth functioning of the social whole — so desirable to the capitalists. This, at least is the model, empirical history is more complicated. The function of art is to address these problems and present “solutions”— that is, to emotionally affect people to struggle or to the acceptance of the current reality, depending on which class the artist is objectively representing (regardless of subjective intentions.) Another important aspect of Plekhanov’s philosophy of art is his view that since history and society create the problems that art attempts to resolve, art is consequently itself a social phenomenon that can be scientifically studied. In this view, artists should not be told what to create and how to create but be left to their own devices to reflect the reality they confront. This view was in conflict with the historical practice of some socialist states in which independent or individual artistic endeavors were discouraged and artists were expected to support the policies and viewpoints of the political leadership. Nothing in the works of Marx and Engels gives warrant for such practices in relation to artistic creation. Such overdetermination in the cultural and social milieu of the people in fact led to an alienation of the people from the political leadership and brought about its downfall. In Art and Social Life Plekhanov does not take sides on the two opposite views on the nature of art — the art for art’s sake view and the “utilitarian” view— i.e., that art must serve some socially useful purpose. Instead, Plekhanov describes the type of social environment, historically produced, which gives rise to one or the other view. Plekhanov has no interest in telling artists what they should do — he is only interested in delineating the types of societies in which these two outlooks occur and predominate. This is what Plekhanov concludes: ‘’The tendency of artists, and those who have a lively interest in art, toward art for art’s sake, arises when they are in hopeless disaccord with the social environment in which they live.’’ ‘’The so-called utilitarian view of art, that is to say, the inclination to attribute works of art the significance of judgment on the phenomenon of life, and its constant accompaniment of glad readiness to participate in social struggles, arises and becomes stronger wherever a mutual sympathy exists between the individuals more or less actively interested in artistic creation and some considerable part of society.’’ The proper role of the socialist state, I suggest, on the Plekhanov model is to allow the maximum possible artistic freedom, seeing the products of artistic creation as reelections of the true feelings and beliefs of various segments of society. In this sense artworks can be seen as ‘’alienation detectors,’’ on the one hand, or ‘’support detectors on the other. To censor artistic creation and prevent its expression simply covers over, without solving, the problems and contradictions in social reality that artworks bring to light. In a socialist state this creates needless alienation between the political and cultural needs of the people and can lead to the isolation and estrangement of the political leadership from its roots in the masses. Plekhanov’s contribution to the creation of a Marxist aesthetic is only one of the many reasons the reading and continuing study of his works is still relevant and important. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed