|

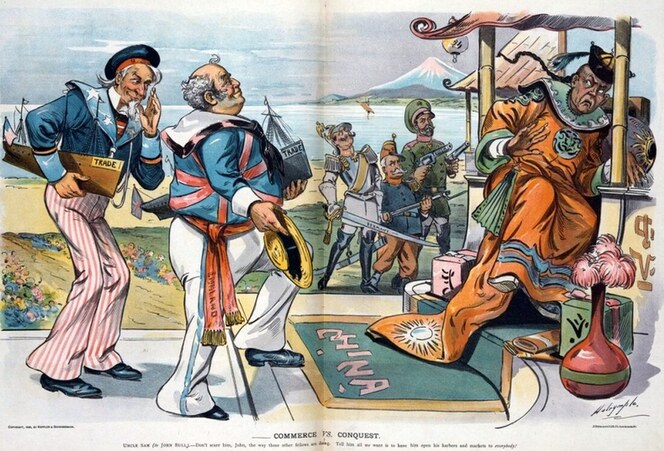

Commerce vs Conquest – “Uncle Sam (to John Bull) Don’t scare him, John, the way those other fellows are doing. Tell him all we want is to have him open his harbors and markets to everybody!” Political Cartoon from 1898. The conquest of one territory and its population by another power has been a prominent part of much, if not all, of the history of human civilisation. While such conquests appeared to occur even in very early periods of history, conquest reached its various peaks with the emergence of great extensive empires. These occurred especially based on the Eurasian continent, and its close neighbour North Africa. Egyptian, Persian, Greek, Roman, and in Asia, various East Asian based empires, including Chinese, conquered and ruled extensive areas. In Europe, the various small kingdoms raided each other but also engaged in conquest and occupation, including the Vikings of Scandinavia. France and Austria, for example, all held extensive territory and different times, as did Russia. Prior to the 16th century these conquests were constrained by as yet undeveloped means of transportation. Ships still relied to a large extent on rowers to assist sailing and were relatively small. The Romans built stone roads which assisted their expansion. Earlier, Alexander the Great was able to take his army all the way to India. However, the technology was not yet there to sustain global or semi-global empires. By the time naval technology and mapping had begun to enable more extensive exploration by the richer European powers, conquest already had thousands of years of history. That powerful states would wage war to conquer and either occupy or subjugate the populations under other states in other territories was “accepted” as inevitable. “Accepted” needs to go in quotation marks because as inevitable conquest seemed in those times, the targets of conquest always resisted, and the peoples being subjugated regularly rebelled. Be that as it may, nobody among the ruling classes of the day seriously struggled for an end to the practice of conquest – except by securing their own conquests as permanent. The inevitability of the need for conquest was a fundamental part of the hegemonic ideology. It was not until the 20th century that the right to conquest began to be questioned from within the various ruling classes of the imperialist countries. The devastation of World War I gave birth to the League of Nations, one of whose premises was that wars, usually wars of conquest, had to be prevented. Then, out of the devastation, suffering and alienation of the Great Depression arose fascism. Nazi Germany, and later Japan, attempted massive wars of expansion. Germany even tried to conquer both the Soviet Union and Great Britain, as well as West and Eastern Europe and North Africa. Japan tried to conquer Korea, China and Southeast Asia, and also targeted Australia. Out of World War 2 came the United Nations whose Charter and other documents also de-legitimise conquest. That was supposed to end. The world would consist of sovereign nations who would settle differences peacefully – and indeed the very idea of conquest was ruled out. The End of Conquest and its Blind Spot The League of Nations, but especially the United Nations, de-legitimised conquest being any part of the future of humanity. But it also began a process of ending a form of conquest that all the European powers as well as the United Stated and Japan had been guilty of – colonial conquest. From the 16th century onwards, naval technology and science began to allow European powers to send ships, often carrying the new advance in military technology of the cannon, far from their own continent to the Americas, Africa and Asia. Colonial conquest began – piecemeal at first as small local states were subdued – but later larger states and territories were conquered, subdued and sometimes occupied. Two thirds to three quarters of the world were conquered and subjugated by the United Kingdom, Spain, France, the Netherlands, Italy, America, Japan and to a lesser extent Germany. Struggle for freedom from subjugation, that is, for independence from the conquering power, began in the 18th century in South America, where genocide and occupation had produced ruling classes and demographics that promoted the formation of serious pre-national communities. In Asia and Africa, while rebellion was almost constant, political and military movements with strategies to end their state of conquest developed more strongly in the 20th century. Anti-colonial revolutions started to emerge alongside the new, revolutionary processes of nation creation, dissolving or transforming the social formations that had existed under earlier pre-capitalist modes of production. In Asia, most of these anti-colonial revolutions were able to make use of the weaknesses of the European powers and Japan, and even the United States, during and after WW2 to escalate their struggles. But despite the decolonisation mandate of the United Nations, in reality the colonies were a blind spot as regards the illegitimacy of conquest. While the British conceded quickly in India, it took decades of armed resistance and many, many deaths in the British colonies in Africa and Southeast Asia before decolonisation began. The French fought for more than another decade after WW2 to retain their earlier conquests in Indochina and North Africa. And even when the French withdrew from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, the United States intervened with massive military force to prevent the completion of national liberation and social revolution. The Dutch ruling class, despite the formation of the United Nations, sent an army back to the Dutch East Indies far away in Southeast Asia to reconquer their earlier conquests. They even granted amnesty to Dutch Nazis if they agreed to go and fight. The United States negotiated for the independence of the Philippines, but intervened militarily in Korea and Vietnam, and were heading towards an attempt to invade Cuba – prevented by Cuban and Soviet military moves. Repeats of the Nazi war of conquest, of wars among the small number of countries that dominated the world’s economy, the imperialist countries, was made illegitimate. As for the colonies’, even ongoing occupation was defended as legitimate until the anti-colonial resistance forced concessions or defeated the conquest. There was also the Soviet Union, a joint founder of the United Nations with veto power on the Security Council. Having seen how the Soviets fought the Nazis, conquering the Soviet Union appeared an impossible project for the imperialist powers. So, the threat of destruction, rather than conquest, was made with the dropping of atomic bombs on Japan. All this led to the madness of MAD – Mutually Assured Destruction. But as for a war of conquest against the formerly colonised world? that remained legitimate. And this was always a fundamental rule of the whole colonial period: one rule for the colonisers and another for the colonised. Contemporary Consequences Even while independence was won by many countries, their original conquest with its massacres, massive plunder and blockage of development and progress has never been recognised as illegitimate. A country like Indonesia was plundered of tens of billions of dollars, as calculated by scholars of colonial finances, while there was no education system, nor any modern manufacturing, built by the Dutch. Debt and savage socio-economic backwardness were the legacies of Dutch colonialism. It was little different in any other colony. Two thirds of humanity were colonised when European superiority in naval and military technology was used for conquest and plunder, and not for spreading Liberty, Fraternity and Equality. The scientific revolution and the Enlightenment were not able, and did not at all, challenge the morality of conquest. Indeed, even in 1945, it was the destructiveness of modern warfare that de-legitimised policies of conquest, not any philosophical rejection. The refusal to address the consequences of colonialism for that huge section of formerly colonised humanity has not simply meant avoiding any discussion of reparations. In fact, the socio-economic backwardness of Global South countries has been exploited as a weakness to allow them to be further plundered and subject to imperialist economic stranglehold. Whenever necessary, they are subject to invasion, low-intensity military intervention, shock-and-awe terror bombing, coups and whatever else might be deemed necessary. After WW2 it has been the states who dominate NATO, particularly the United States as well as some junior allies such as Australia which have shown that as far as the Global South countries go, conquest is still legitimate, even if not always in military form. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the reduced economic strength of the Russian Federation – even while nuclear armed – this attitude frames American policy towards Russia, as well as China. Russia and China are, at the moment, the largest of the defiant states – in defence of their own development, even if on a capitalist economic path, or some hybrid of that. The idea that conquest is still legitimate is primarily propelled by imperialism’s need, especially the United States’ need, to deepen its exploitation of the Global South and their ruling class’s perpetual colonial mentality. However, if this openness to conquest is allowed to grow all, hell can break loose, literally. To struggle against war and for peace today means strengthening solidarity with countries of the Global South in all of their efforts to defend themselves from attempts at imperialist conquest, whether direct military attacks, by encirclement, by proxy wars, economic blockades or commercial wars. The vast majority of Global South countries are ruled by capitalist classes whose thinking about how they should defend themselves may often be characterised by the narrowness of their class outlook, ignoring the role of popular forces in their own or other countries. They may not make the best decisions, although indeed they may also make the only decisions available to them, which may still be horrible. What should determine a sane, humane outlook is whether or not imperialism’s stranglehold on the Global South will be strengthened or weakened. The weaker the stranglehold, the greater potential for new movements to emerge and grow. And, of course, there are some Global South countries that are governed by genuine socialist governments and peoples, such as Cuba. For such countries a special solidarity is due. And never forget, the US regularly breaks its promises. So yes, President John Kennedy did promise not to invade Cuba, but while conquest is still considered legitimate among the imperialists, solidarity is a necessary part of a legitimate wariness. Archives September 2023

1 Comment

10/1/2023 09:32:25 am

For those seeking a non-Marxist empirical treatment of what he called "Open Door Imperialism," see William Appleman Williams.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed