|

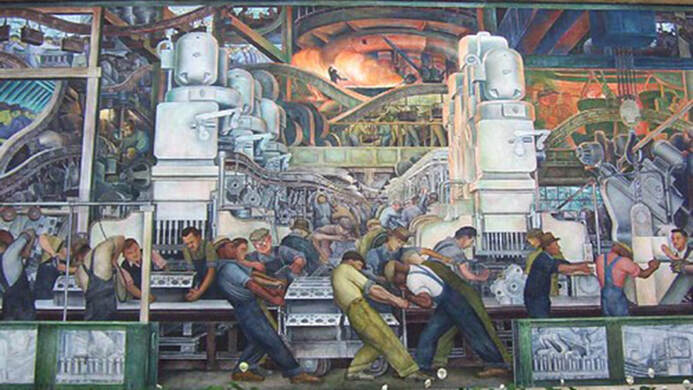

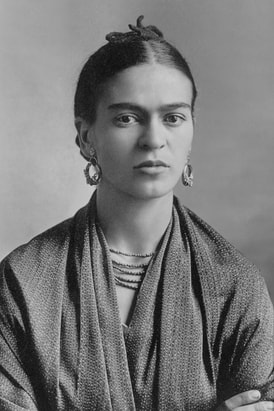

“I still call myself a Communist, because Communism is no more what Russia made of it than Christianity is what the churches make of it.” — Pete Seeger, The New York Times Magazine, 1995 Many artists have called themselves communist or have been members of communist parties around the world. One would think that with artists like Pablo Picasso, Dashiell Hammett, and Jean-Luc Godard, communism would receive some kind of recognition for its artistic contributions. These three alone are giants in their respective fields. So, where is the praise for Communist artists? I imagine it remains locked up in a vault somewhere alongside the Islamic Golden Age — that fertile period in world history when artists and thinkers in Baghdad and Muslim Spain made monumental contributions to the arts and sciences, contributions that, for political reasons, remain unknown to many Westerners. Those who adhere to right-wing politics are not inclined to give due respect to the contributors of the Islamic Golden Age (mostly Brown and Black people) for their groundbreaking work in astronomy and mathematics. I’m sure they feel the same way when it comes to giving Communist artists their proper due. Revolutionary artists Many communist artists are household names. Spanish master Pablo Picasso is one of the movement’s greatest artists, having cofounded the Cubist movement, co-invented the collage, and created some of the most influential works of art in modern art history. His 1907 painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon resulted in Picasso eclipsing Henri Matisse to become the leading figure in modern art. Art critic Peter Plagens, in a 2007 Newsweek article, called it “the most important work of art of the last 100 years.” Picasso’s Guernica (1937), which is one of the artist’s best-known works, is regarded by many art critics as the most powerful anti-war painting in history. In the words of Chicago Sun-Times columnist Alejandro Escalona, “Guernica is to painting what Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is to music.” Picasso, who had joined the French Communist Party in 1944 and remained a loyal member of the Party until his death, was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize in 1962. Picasso dominated Western art in the 20th century, but he wasn’t the only Communist painter from that century who had an immense impact on the art world. In Mexico, two giants emerged and carved out their own place in art history. Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo are not only two of Mexico’s most revered artists, but they’re also two of the most important artists to ever come out of Latin America. Assuming for a moment that Diego Velázquez, Francisco Goya, Pablo Picasso, and Salvador Dalí are “Hispanic” and not white Europeans (Spaniards), as I consider them to be, Rivera and Kahlo would rank alongside those masters as the greatest Latino/a artists the world has ever known. In the 1920s, both Rivera and Kahlo had joined the Mexican Communist Party, through which they met and later married. (Rivera was later expelled from the Party for being a “Trotsky sympathizer,” and though he was indeed a Trotskyist, he remained a devoted Communist throughout his life.) Along with David Alfaro Siqueiros, also a Communist, Rivera is among the most celebrated Mexican muralists of the 20th century. He was an idealist who, through his art, created a mythology around the Mexican Revolution and promoted Mexico’s indigenous past, while simultaneously advocating Marxist beliefs. Rivera could turn his hand to any style, from Cubism to Post-Impressionism, and he was responsible for the revival of fresco painting in Latin America. Since his death, the Mexican government has declared Rivera’s works as “monumentos historicos,” and in 2018, his painting The Rivals became the highest-priced Latin American artwork ever sold at an auction.

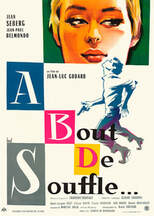

Initially overlooked as simply the wife of Diego Rivera, Kahlo is now widely regarded as one of the most renowned painters. In her native country, Kahlo’s work has been declared part of the national cultural heritage, prohibiting their export from Mexico. In the United States in 2001, Kahlo became the first Latina to be honored with a U.S. postage stamp. Communists in film Picasso, Rivera, and Kahlo could be considered “the big three” Communist artists, but the Mount Rushmore of Communist artists wouldn’t be complete without a fourth figure, and there is none more befitting than French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard, who, according to Filmmaker magazine, boasts “the most influential body of work in the history of cinema.” Put simply, without Godard, there would be no Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, or Wes Anderson. A pioneer of the French New Wave, Godard invented what so many artists and even social media “creators” on YouTube and TikTok today take for granted. The retro, self-conscious, postmodern aesthetic that permeates the modern world (whether in movies, music, television, or the internet) comes directly from Godard and the French New Wave.

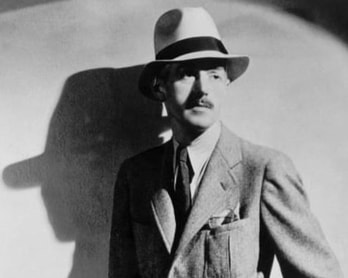

“Modern movies begin here,” Roger Ebert said of Breathless, in a retrospective review. “No debut film since Citizen Kane in [1941] has been as influential,” he added. At the time, the movie’s unconventional use of jump cuts — an editing technique in which a single continuous shot is broken into two parts — was nothing short of revolutionary, and can now be seen in nearly every video on YouTube and TikTok, and of course, in many movies. It could be said in earnest that Godard walked so the rest of us could run. In 2010, Godard was awarded an Academy Honorary Award. Another giant of the film industry was Sergei Eisenstein, aka “the father of montage,” who was a pioneer of early cinema. Think D. W. Griffith, but whereas Griffith’s shameful The Birth of a Nation (1915) inspired the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan, Eisenstein’s work lifted workers’ and peasants’ voices while revolutionizing cinema. (When Google celebrated Eisenstein’s 120th birthday in 2018 with a “Doodle,” right-wing Americans let their displeasure be known by praising the racist Griffith.) Ten years after the release of The Birth of a Nation, Eisenstein released what Roger Ebert called “one of the fundamental landmarks of cinema,” Battleship Potemkin (1925). It was named the greatest film of all time at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair and has since consistently been ranked among the greatest and most influential movies ever made.1 (When I took a film course in college, Battleship Potemkin was the first movie our professor showed us — not The Birth of a Nation or Citizen Kane.) Battleship Potemkin depicts a real-life mutiny that occurred in 1905 and is now viewed as a precursor to the Russian Revolution. Fearing that anyone who saw the film would be turned into a Communist, various federal and municipal U.S., French, German, and British governments banned it. The film was banned for a longer time than any other film in British history, from 1926 to 1954. Eisenstein, who had been invited to Hollywood in 1930 to make a movie for Paramount Pictures, became the target of anti-Communists, and his projects were rejected by the studio. Those on the Right would have you believe that Hollywood is (and always has been) a bastion of the Left — the same Hollywood that was once dominated by old, white, anti-Semitic Protestant men who produced propaganda movies like I Was a Communist for the FBI (1951) and Red Dawn (1984), and who fawned over Ronald Reagan in his early years as an actor. Vladimir Lenin once remarked that film was “the most important of the arts,” so it should come as no surprise that, in 1920, the Soviet Union established one of the largest and oldest movie studios in Europe, Mosfilm. Aside from Sergei Eisenstein’s work, other acclaimed movies to come out of the Soviet Union include Mother (1926), Man with a Movie Camera (1929), Earth (1930), Cranes Are Flying (1957, winner of the Palme d’Or at the 1958 Cannes Film Festival), Ballad of a Soldier (1959), I Am Cuba (1964), War and Peace (1966–67; Academy Award and Golden Globe winner), Come and See (1985, generally considered one of the finest war movies ever made), and the many masterpieces of one of world cinema’s greatest directors, Andrei Tarkovsky, whose most notable films include Andrei Rublev (1966), Solaris (1972), Mirror, (1975), and Stalker (1979). Not all the directors of these masterworks were Communists. How much this matters is up for debate. Whether or not the great scientists and mathematicians of the Islamic Golden Age were Muslim is irrelevant (most were Muslim, others Jewish, and some Christian). What matters is that Islamic states in Baghdad and Muslim Spain nurtured intellectual thought — and for a while, the same thing happened in the Soviet Union, albeit on a smaller scale. The U.S. film industry also had its share of Communists. Hollywood actors include comedian Lucille Ball, a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Golden Globe Cecil B. DeMille Award, and the Kennedy Center Honors; and Sterling Hayden, best-known for his work in The Asphalt Jungle, Dr. Strangelove, and The Godfather. And there were the “Hollywood 10,” the movie producers, directors, and screenwriters who were brought before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947, refused to answer questions about their political affiliations, and were mostly blacklisted afterward. The most outspoken film actor during the McCarthy period was more of a Renaissance man than a creature of Hollywood, the multi-talented Paul Robeson — athlete, singer, and stage and film actor. In 1951 he and William Patterson, Secretary of the Civil Rights Congress (CRC), presented to the United Nations a petition on behalf of the CRC titled “We Charge Genocide: The Crime of Government against the Negro People,” which documented lynchings and other forms of violence against African Americans. Literary leftists Dashiell Hammett, dubbed “the dean of the . . . ‘hard-boiled’ school of detective fiction” by the New York Times, is widely regarded as one of the greatest mystery writers of all time, best-known for having penned Red Harvest (1929), which was included in Time magazine’s list of the 100 best novels published in the English language between 1923 and 2005, The Maltese Falcon (1930), and The Glass Key (1931). His work also appeared in the highly popular pulp magazine Black Mask.

He was found guilty of contempt and served time in a West Virginia federal penitentiary, where he was reportedly assigned to clean toilets. Hammett’s popularity waned thereafter, and he soon found himself blacklisted when, in 1953, he testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee about his own Communist activities, but refused to cooperate with the committee. Impoverished, Hammett sank deeper into alcoholism, which had plagued him for years, and he died in 1961. A veteran of both world wars, Hammett was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Other great Communist authors worthy of mention include Theodore Dreiser, who authored the 1925 classic An American Tragedy; Portuguese Nobel laureate José Saramago; Jorge Amado, who remains the best-known of the modern Brazilian writers; Meridel Le Sueur, who joined the CP in 1925, wrote for the New Masses, and was blacklisted in the 1950s; Richard Wright (he left the Communist Party, though he remained a Marxist); Maxim Gorky, a five-time nominee for the Nobel Prize in Literature; and Tillie Olsen, who in 1961 won the O’Henry Award for her short story “Tell Me a Riddle.” Well-known Communist poets include Mahmoud Darwish, who is regarded as the Palestinian national poet; Greek poet Yiannis Ritsos; Rafael Alberti, who is heralded as one of the greatest literary figures of the so-called Silver Age of Spanish literature; Pakistani poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz, who was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature and awarded the Lenin Peace Prize; Pablo Neruda, often considered the national poet of Chile (he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature and was called “the greatest poet of the 20th century in any language” by noted Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez; Louis Aragon, a leading voice of the Surrealist movement in France; and Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén. Musical communists In the music world there are American rappers Dead Prez and Noname and singer-songwriters Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger, both Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees and Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award honorees; and Mikis Theodorakis, a beloved Greek composer of modern classical music and recipient of the Lenin Peace Prize. Theodorakis, who died in September 2021, scored the music for the films Zorba the Greek and Serpico. Another big name is the influential hip-hop artist Tupac Shakur. He was not a card-carrying member of the Communist Party, but he did join the Baltimore Young Communist League while in his teens. One only has to listen to Shakur’s music, which often addresses social issues, to see that the Communist ideals he inherited in his youth carried over into his adulthood. Listening to Shakur’s interviews, in which he talks about inequality and other social issues, will give you an idea of his politics. Shakur’s most acclaimed albums, Me against the World (1995) and All Eyez on Me (1996), are regarded as classics of the hip-hop genre, and his song “Dear Mama” was added to the National Recording Registry in the Library of Congress in 2009. Eight years later, Tupac Shakur was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. It’s hard not to be impressed by communism’s astounding contributions to the arts, especially since the communist movement is relatively young. Yet there are untold numbers of communist artists — some famous, others less so, some who are Communists with a capital “C,” others who think like communists — who have brought their unique visions to the world. The arts are all the richer for it. Note 1. The 1958 Brussels World’s Fair was no small matter. At the event, 117 film critics and historians from 26 nations selected the 12 greatest films of all time in what is now considered the first universal film poll in history, with Battleship Potemkin being named the greatest film of all time, ahead of the works of Charlie Chaplin and Orson Welles. Images: River’s Detroit Industry Murals (Wikipedia, public domain); (Picasso’s Guernica (Wikipedia, fair use); Frida Kahlo (Wikipedia, public domain); Movie poster for Godard’s Breathless (Wikipedia, fair use); Shots from Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (Wikipedia, public domain); Dashiell Hammett (Wikipedia, public domain). AuthorNino Hoti This article was produced by CPUSA. Archives November 2021

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed