|

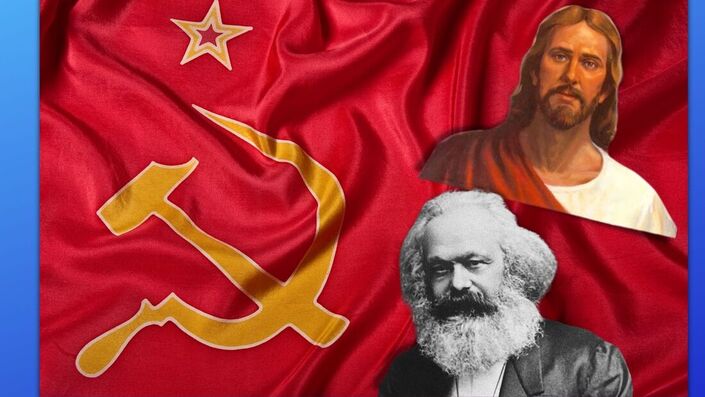

The Battle for God is an ambitious book by the popular writer on religion Karin Armstrong. In it she attempts to explain the origins and goals of the major fundamentalist movements in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. It is a heroic attempt which she ultimately fails to accomplish. Along the way, however, she presents a useful, if fanciful, account of the history of religious fundamentalism over the last 500 years. Why do I think she fails to accomplish her task of explicating the origins and goals of fundamentalism? The reason is she does not really understand the social role of religion and its relation to the economic base of society. Her explanations are almost uniformly conditioned by idealistic fantasies on the nature of religion as an independent force which exists in order to make us better people (more compassionate) and to help us find a truth about the nature of life that reason cannot provide. She tells us that in olden times there were two ways of thinking and “acquiring knowledge”— namely, “mythos” [religion] and “logos” [philosophy/science]. Then religion was primary as it gave meaning to life while science “enabled men and women to function well in the world …[it] could not assuage human pain or sorrow. Rational arguments could make no sense of tragedy.” In other words, religion is a support which people who cannot face the world science reveals to them fall back upon to find comfort. The book is divided into two unequal parts. The shorter first part deals with the prehistory of modern fundamentalism from 1492 [the expulsion of Moslems and Jews from Spain] to 1870. It is well worth reading for the orientation it gives on the pre-modern relations between traditional religion and science. Islam, for example, after an earlier embracing of science, or at least toleration, and critical thinking in its first centuries, found itself confronted with social conditions [Mongol invasions, conflicts with the West] that led it to retreat from rationality into mysticism and dogmatism: forces also at work in Judaism and Christianity for other reasons. Some of her explanations are unacceptable, however. In her chapter “Jews and Muslims Modernize” we are informed the “Jews would … have to adopt modernity in an atmosphere of hatred,” which she blames on the “modern ethos” of the Enlightenment and on Karl Marx who “argued that the Jews were responsible for capitalism which in his view was the source of all the world’s ills.” She mentions in passing, many pages later, that Christianity had been anti-Semitic for centuries. It will come as news to Marxists that Marx blamed capitalism on the Jews. This would be a big disappointment to the ultra-rightists who blame them for communism. Nietzsche blamed them for Christianity. It will also be news that all the ills of the world are due to capitalism. Marx and Engels devoted many pages to the problems and the “ills” of pre-capitalist economic formulations that plagued humanity - serfdom in Russia, feudalism and feudal land tenure in Germany and Eastern Europe. It might surprise Ms. Armstrong that Marx and Engels even spoke of the progressive role that capitalism had played in world history. She justifies her claim that Marx held the Jews responsible for capitalism by a general reference (no quote) to an early work of his, “On the Jewish Question.” Had she read this work she would be hard pressed to find any statement by Marx to the effect that the Jews were responsible for capitalism. This, despite her own comment about “ the fabled business acumen of the Jews.” If Ms. Armstrong’s readers are interested in Marx's views on the origin of capitalism they should be referred to the first volume of Das Kapital. Part Two deals with fundamentalism per se. She provides a detailed history of its development in the 20th Century focusing on Iran, Israel, and the U.S—Pakistan and Egypt also come in for special mention. These are important chapters as she relates some of the more extreme movements in Islam to the reaction of the fundamentalists to the aggressive policies of imperialism and its Zionist offshoot. However, we are also told that the main reason for fundamentalism is that for humans it is almost impossible to live without a religious belief in the ultimate meaning of life and that fundamentalism is a reaction to the extreme threat of the Western scientific outlook to this religious need especially as it is manifested in less developed areas. She maintains that these ultimate questions of meaning cannot be addressed by science. (She means, fundamentalists do not like the answers of science). Armstrong discusses the recent history of the West in order to show that science is no substitute for religion. World War I was brought about by “a nihilistic death wish, as the nations of Europe cultivated a perverse fantasy of self-destruction.” A good dose of Lenin’s Imperialism the Highest Stage of Capitalism would remedy this mis-diagnosis of the causes of the First World War. Nevertheless, we get a good introduction to the men who founded modern fundamentalist movements. Unfortunately, too much of Armstrong’s criticism is based on her own religious sensibilities. She condemns the violence of fundamentalism because she thinks that it violates “one of the central tenets of all religion: respect for the absolute sanctity of human life.” Distressingly, no such central tenet exists for any of the world’s religions, as their bloodstained histories attest. She does mention the expulsion of the Palestinians from their homes by Zionism, and the Western role in the overthrow of Musaddiq and the restoration of the Shah in Iran. But these appear as incidental to the root cause of fundamentalism which is rooted in man’s search for meaning which has been road blocked by the Western scientific outlook. She tells us WWII, the Holocaust, and the bombing of Hiroshima demonstrate “the limits of the rationalist” worldview. “Reason is silent: there is — literally— nothing it can say.” She appears to view the Nazis as the products of “unfettered rationalism” [!] and again, the mass destruction of WWII reveals “a nihilistic impulse.” What can the response be to Armstrong’s position? I can only say that reason is not silent but has in fact, through the medium of Marxist analysis, explained the reasons for the wars and acts of mass destruction which the imperialist system, in its quest for market supremacy and economic domination has, and is still inflicting, on the people’s of the world. The attack on reason as inadequate and unable to explain our world, a mainstay of the arguments of bourgeois commentators, is motivated by a refusal to admit that a rational solution involves a Marxist solution. The existing capitalist relations of production are irrational and engender the contradictions in the world economy. It is these relations, not the nihilistic impulses of European rationalists, that have been, and still are, responsible for the social anarchy we see about us. Still, this book is recommended for the mountain of facts, names, movements, and historical accounts given of the fundamentalist religious movements of our times. But her conclusions are themselves nothing more than religious nonsense. “At the end of the twentieth century, the liberal myth that humanity is progressing to an ever more enlightened and tolerant state looks as fantastic as any of the other millennial myths we have considered in this book. Without the constraints of a higher mythical truth, reason can on occasion become demonic and commit crimes that are as great as, if not greater than, any of the atrocities perpetrated by fundamentalists.” Reason will not take the rap for the irrationality of the capitalist system, and no higher ‘’mythical truth’’ will solve the problems of humanity. The solution remains as it was first enunciated to the world in 1848 in The Manifesto of the Communist Party. The working people of the world must unite to end the oppression of an economic system that puts profits, at any cost, before the well being of humanity. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. He is the author of Reading the Classical Texts of Marxism. Archives July 2022

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed