|

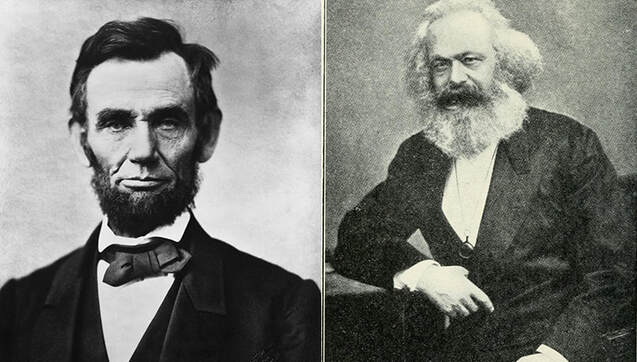

Marx strongly supported the Union from the outset, saw the slaveholders confederacy as the principal enemy, and attacked those British liberals and radicals who were condemning Lincoln for not immediately advocating the abolition of slavery. In this excerpt from an 1861 article in the New York Tribune, where he is writing positively about a response from Harriet Beecher Stowe to Britain in defense of the Lincoln government, Marx makes this important critique of both honest and hypocritical anti-slavery thinking. He also made the point that many who are critical of Lincoln denounced the John Brown raid and said that a revolution of the slaves was worse for civilization than slavery. “This is, in fact, a masterly piece of logic. Anti-Slavery England cannot sympathize with the North breaking down the withering influence of slaveocracy, because she cannot forget that the North, while bound by that influence, supported the slave-trade, mobbed the Abolitionists, and had its Democratic institutions tainted by the slavedriver’s prejudices. She cannot sympathize with Mr. Lincoln’s Administration, because she had to find fault with Mr. Buchanan’s Administration. She must needs sullenly cavil at the present movement of the Northern resurrection, cheer up the Northern sympathizers with the slave-trade, branded in the Republican platform, and coquet with the Southern slaveocracy, setting up an empire of its own, because she cannot forget that the North of yesterday was not the North of to-day. The necessity of justifying its attitude by such pettifogging Old Bailey pleas proves more than anything else that the anti-Northern part of the English press is instigated by hidden motives, too mean and dastardly to be openly avowed. ” But let’s continue: Marx’s 1864 letter of congratulation to Lincoln on the in the name of the Internationale is very well known and in its larger arguments on slavery and history the most important document. This except from a letter to Johnson after the assassination of Lincoln (Marx encouraged Johnson to carry forward the Reconstruction, which of course Johnson did not d) portrays Lincoln as both a son of the working class and a hero in advancing the struggles for democracy: “It is not our part to call words of sorrow and horror, while the heart of two worlds heaves with emotions. Even the sycophants who, year after year and day by day, stuck to their Sisyphus work of morally assassinating Abraham Lincoln and the great republic he headed stand now aghast at this universal outburst of popular feeling, and rival with each other to strew rhetorical flowers on his open grave. They have now at last found out that he was a man neither to be browbeaten by adversity nor intoxicated by success; inflexibly pressing on to his great goal, never compromising it by blind haste; slowly maturing his steps, never retracing them; carried away by no surge of popular favor, disheartened by no slackening of the popular pulse; tempering stern acts by the gleams of a kind heart; illuminating scenes dark with passion by the smile of humor; doing his titanic work as humbly and homely as heaven-born rulers do little things with the grandiloquence of pomp and state; in one word, one of the rare men who succeed in becoming great, without ceasing to be good. Such, indeed, was the modesty of this great and good man, that the world only discovered him a hero after he had fallen a martyr.” Marx also in private letters to Engels as early as June 1865 began to doubt that Lincoln would carry forward the necessary anti-slavery democratic policies, while capitalist opinion in Europe and Britain began to look at him positively. Here by the way is a general philosophical statement on the war and Lincoln in which the nature of the class struggle between slaveholders and the new forces of developing industrial capital for whom the slave system was a fetter is expressed by Marx: “[T]he number of actual slaveholders in the South of the Union does not amount to more than 300,000, a narrow oligarchy that is confronted with many millions of so-called poor whites, whose numbers have been constantly growing through concentration of landed property and whose condition is only to be compared with that of the Roman plebeians in the period of Rome’s extreme decline. Only by acquisition and the prospect of acquisition of new Territories, as well as by filibustering expeditions [i.e. conquests of other lands, such as in Central America—ISR], is it possible to square the interests of these “poor whites” with those of the slaveholders, to give their restless thirst for action a harmless direction and to tame them with the prospect of one day becoming slaveholders themselves.” In the aftermath of the Emancipation Proclamation , Marx wrote this: “So far, we have only witnessed the first act of the Civil War—the constitutional waging of war. The second act, the revolutionary waging of war, is at hand.” Here, when the Confederates were winning in 1862, and division and corruption characterized the North, Marx wrote this–by the way–the term “white trash” goes back to pre civil war times and was known in Europe Marx uses it in quotes, but he is talking about the non slave holding whites who slaveholders could control for slave patrols, militias to seize the lands of native peoples, but kept at arms length. The comment about a revolution in the North was as always an example of Marx’s optimism: “The manner in which the North wages war is only to be expected from a bourgeois republic, where fraud has so long reigned supreme. The South, an oligarchy, is better adapted thereto, particularly as it is an oligarchy where the whole of productive labor falls on the **** and the four millions of “white trash” are filibusterers by profession. All the same, I would wager my head that these boys come off second best, despite “Stonewall Jackson.” To be sure, it is possible that it will come to a sort of revolution in the North itself first”…. Finally, this analysis of why Lincoln, not an abolitionist not a revolutionary in terms of his consciousness, would be destined to become one: “Lincoln is not the product of a popular revolution. This plebeian, who worked his way up from stone-breaker to Senator in Illinois, without intellectual brilliance, without a particularly outstanding character, without exceptional importance—an average person of good will, was placed at the top by the interplay of the forces of universal suffrage unaware of the great issues at stake. The new world has never achieved a greater triumph than by this demonstration that, given its political and social organization, ordinary people of good will can accomplish feats which only heroes could accomplish in the old world!” AuthorNorman Markowitz teaches history at Rutgers University and was a contributing editor of Political Affairs Magazine. This article was republished from CPUSA. Archives July 2021

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed