|

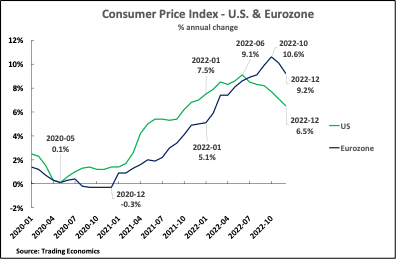

2/23/2023 Key Lessons From the Failure of the U.S. and Success of China’s Economic Stimulus Programs By: John RossRead NowIntroduction It is well known that China will continue economic stimulus measures in 2023—the only serious discussion is of what type. To be successful these measures must simultaneously achieve two goals. First, they must adequately respond to China’s short-term situation—that is they must substantially reverse 2022’s economic slowdown. Second, they must aid in achieving the strategic goals China has set for 2035. It is equally well known that the international economic situation which will confront China in 2023 is unfavorable. In this regard, it is important to understand that this negative international context is itself due to the failure of the stimulus programs the U.S. launched to deal with the consequences of the COVID pandemic. The fact that China and the U.S. have both now released their economic data for 2022 as a whole allows this situation to be judged clearly. In 2022 the U.S. suffered its worst stagflationary crisis for almost half a century—the EU’s similar situation merely followed a few months behind the U.S. In detail, the U.S. experienced the highest inflationary wave for forty years while simultaneously its economic growth rate has dropped by half compared to that earlier period. These two factors, in turn, combine to produce a U.S./EU economic policy paralysis in adequately responding to their short-term slowdown in 2023—high inflation means their policymakers must adopt economically contractionary policies, in particular raising interest rates, which fail to offset, indeed intensify, economic slowing. In summary the result, as will be shown in detail, is not only short-term U.S./EU economic deceleration in 2023 but a medium-/long- term slowdown which prevents these economies achieving their strategic objectives. That is, the U.S. stimulus programs was a strategic failure—in addition to the short-term inflation, prospects for long-term economic growth were worse after these packages than before them. In summary, the present world economic situation, and therefore the one facing China, is largely determined by the interrelation of two stimulus programs. The first is the damaging consequences of the U.S. stimulus packages, creating the worst global stagflationary situation for forty years, the second is the stimulus programs being launched by China which have the potential both to launch its own economic growth and to play a key role in global economic recovery. Given these facts it is, therefore, clarificatory for achieving China’s goals to examine in detail the present international economic situation and understand the reasons for the failure of the U.S. packages, and the lessons of these for China’s own stimulus programs. Two interrelated but distinct issues are involved with this—both of which directly relate to China’s own economic situation and policies as it enters 2023.

China’s strategic goals to 2035Turning to the specific interrelation of these international economic issues with China’s strategic goals the latter, in terms of economic growth, were set out in November 2020 by Xi Jinping in 关于《中共中央关于制定国民经济和社会发展第十四个五年规划和二〇三五年远景目标的建议》的说明. This stated that discussion around the 14th Five Year Plan discussion had noted that: “the goal of doubling the economic aggregate or per capita income by 2035 should be clearly stated.” It concluded that: “It is entirely possible to double the total or per capita income.” China doubling per capita GDP from 2020 to 2035 would mean, leaving inflation out of account, achieving a per capita GDP level of $21,050. At the 20th Party Congress the fundamental goal was set as reaching the level of a “medium-developed country by 2035.” Per capita GDP of slightly above $21,000 would be significantly above the level of Hungary or Poland today, that is of major East European states, and slightly above the level of Greece—precisely a medium-developed advanced economy. China’s annual population growth in the recent period has been zero, and in 2022 was slightly below zero, consequently achieving the target of doubling total GDP is extremely close to that for doubling per capita GDP—and ensures that that the latter target will also be met. Therefore, the growth assumptions in what follows are for China doubling GDP by 2035—any realistic estimate of population changes by 2035 will not affect the fundamental economic situation. To achieve doubling of GDP/per capita GDP during 2020-2035, after growth of 3.0 percent in 2022, requires annual average growth of at least 4.6 percent in 2023-2035. Any adequate stimulus program must therefore achieve the tactical goal of accelerating economic growth in 2023 but doing so in a way that simultaneously ensures achievement of the strategic goal for 2035. These requirements will be assumed in what follows. Part 1. The Strategic Failure of the U.S./EU Stimulus Programs |

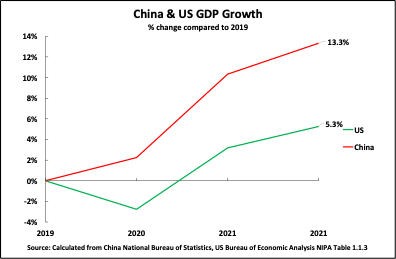

Slowdown in U.S. growth But if U.S. inflation soared during the period of its pandemic era stimulus packages U.S. economic growth was very slow. Recent publication of U.S. economic data for the whole of 2022, which means that three years of pandemic, 2020-2022, are covered shows that U.S. GDP grew by a total of only 5.3 percent during this period—an annual average 1.7 percent. |

U.S. short-term contractionary policies As is well known, to attempt to combat the inflationary wave, the U.S. Federal Reserve, and other Western central banks, have had to, and will continue for some time, to increase interest rates and tighten monetary policies with inevitable contractionary economic effects. |

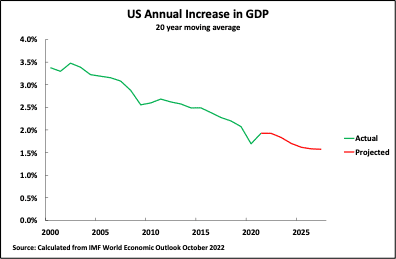

For this reason, not only will the U.S./EU’s 2023 growth decelerate, but Western economies medium/ long-term growth—in particular, that of the U.S. —will slow, as even the IMF, whose predictions are normally somewhat biased in favor of the U.S., admits. Figure 4 shows that the IMF projects that annual average U.S. GDP growth, taking a long-term average to remove the effect of business cycle fluctuations, will fall from an already low 1.9 percent in 2021 to 1.6 percent in 2027. Over the same period the IMF projects EU annual growth will fall from 1.4 percent to 1.2 percent.

This complete strategic failure of the U.S./E.U. stimulus packages launched against the COVID economic downturn makes clear why it is important that China studies and draws the lessons from this extremely negative experience—as these lessons are linked to fundamental issues of economic policy and therefore also affect China.

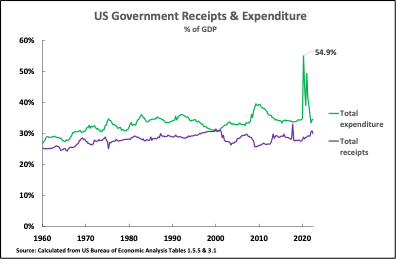

What happened during the U.S. stimulus packages? Turning from the results of the U.S. stimulus packages to the processes which occurred during them, and produced these negative results, by far the largest change was in U.S. government behavior. Figure 5 shows U.S. government receipts and expenditure. |

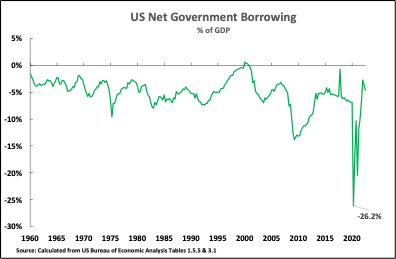

| The vast surge in U.S. government expenditure, with merely a moderate rise in receipts, of course produced a huge excess of expenditure over income and consequently a vast increase in the budget deficit and state borrowing. As Figure 6 shows U.S. government quarterly borrowing soared to an unprecedented peacetime level of 26.2 percent of GDP in the 2nd quarter of 2020. |

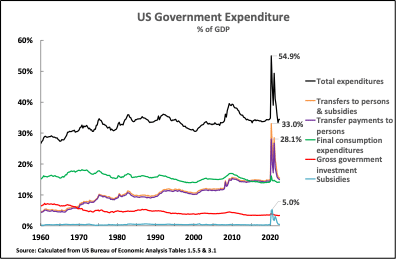

A huge increase in U.S. transfer payments and subsidies

- There was no increase in government investment—it was 3.5 percent of GDP at the beginning of the period and 3.5 percent at the end.

- Government final consumption rose only modestly from 14.1 percent to 16.1 percent of GDP—an increase of 2.0 percent of GDP.

- Government subsidies, above all to transportation and related uses, rose from 0.4 percent to 5.0 percent of GDP in the 2nd quarter of 2020—an increase of 4.6 percent of GDP.

- Transfer payments to persons enormously increased from 14.4 percent to 28.1 percent of GDP—an increase of 13.7 percent of GDP. Payments to individuals accounted for the vast majority of the increase in government spending and were overwhelmingly used for consumption.

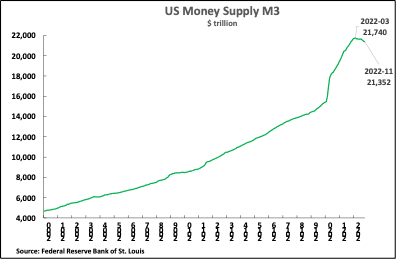

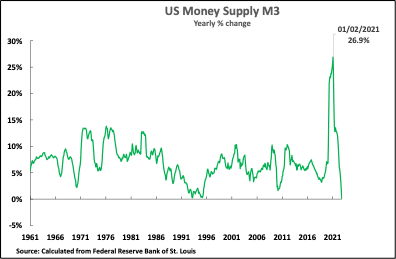

U.S. money supply The huge increase in consumer-focused government transfer payments was in turn accompanied by extremely rapid expansion of the U.S. money supply. Figure 8 shows that in the year to February 2021 the U.S. broad money supply rose by 26.9 percent—by far the most rapid increase in U.S. peacetime history. |

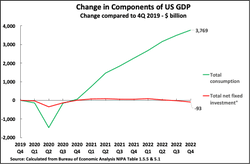

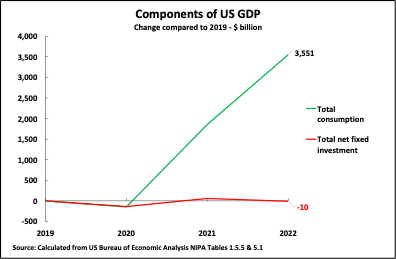

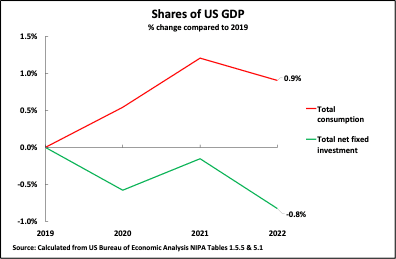

What occurred in the U.S. economy during its stimulus packages? Turning to the impact of these consumer-focused stimulus programs on the U.S. economy, Figure 9 shows the key changes in structure of U.S. GDP during the pandemic—that is, the changes from 2019, prior to the pandemic, to 2022. U.S. consumption rose relatively strongly by $3,551 billion. |

The final outcome of the U.S. stimulus packages

- Strategically the stimulus program was a complete failure—in the short term the inflationary wave forced the introduction of contractionary measures sharply slowing the U.S. economy in 2023, while in the medium/long term annual average the U.S. economic growth actually declined.

Part 2. Confusion of Supply and Demand: Why the U.S. Stimulus Packages Failed

- Confusions in U.S. economic thinking.

- The point in the business cycle at which this consumer-based stimulus was launched.

Confusions in U.S. economic thinking

The most important confusion in popular, more precisely “vulgar,” writing in Western economics is a fundamental and damaging confusion between the economy’s demand side and its supply side. This was used to create a false rationale for the U.S. stimulus packages, with their damaging consequences, and it unfortunately also sometimes appears in sections of China’s media. It is therefore important to clarify this.

This confusion between the economy’s demand and supply sides necessarily fails to understand the different roles played by consumption and investment in the economy, and therefore to an erroneous view that consumption can substitute for investment in terms of economic growth. To be precise:

- Considering first investment, this constitutes part of both the economy’s demand and supply sides. Investment goods and services appear in the economy’s demand side by being purchased (buying of machines, factories etc.) but they are also an input into production together with other factors such as labor—i.e., investment is part not only of the economy’s demand side but also part of its supply side. An increase in expenditure on investment is therefore not only an increase in demand but also an increase in supply—for example, if there is a purchase of a billion yuan of investment goods (machines etc.) there is also automatically a billion yuan increase in overall supply in the economy.

- In contrast to investment, consumption is only a category on the economy’s demand side, it does not appear in the economy’s supply side. This is necessarily the case because, by definition, consumption is not an input into production—if anything is an input into production it is not consumption. Therefore, for example, if there is a billion yuan increase in consumption there is a billion yuan increase in the demand side of the economy, but not any automatic increase in the economy’s supply side. An increase in consumption increases the demand side of the economy but, unlike with investment, it does not automatically increase supply.

Confusion over this fundamental theoretical issue, as will be seen, significantly explains the strategic failure of the U.S. stimulus packages.

A technical note

It is unnecessary here to discuss the differences between these concepts in “Western” and Marxist economic as both agree that investment (capital) is an input into production and therefore part of the economy’s supply side, but neither includes consumption as an input into production—and therefore in both consumption is only part of the economy’s demand side but not of its supply side. Put in technical language, consumption is not an input into the production function—but for non-economists it is sufficient to understand that consumption is not part of the economy’s supply side.

As a result of investment being part of both the economy’s demand side and its supply side, but consumption being only part of the economy’s demand side, if there is an increase in investment demand, that is there is an increase in real expenditure on investment, there is also a direct increase in the economy’s supply side. However, if consumption is increased there is an increase in demand but not any direct increase in supply.

Under certain circumstances, analyzed below, an increase in demand caused by increasing consumption expenditure, may indirectly lead to an increase in production—but this is not at all automatic and also under other circumstances, because consumption is not an input into production, an increase in consumption demand may not lead even indirectly lead to an increase in production. In some circumstances an increase in consumption expenditure may simply create inflation, suck in imports, or both without an increase in production. But in all cases, any increase in output can only occur if there is an increase in the economy’s supply side (that is in labor, capital etc.). Consumption itself provides no input into production and no increase in productive capacity.

The confusions in vulgar Western economic thinking

This confusion over demand and supply sides of the economy, and therefore over the role of consumption and investment, then follows directly from statements such as “With consumption accounting for 67 percent of GDP growth.” If both consumption and investment are an input into production this suggests then one can replace the other. For example, if consumption and investment are both inputs into production, and therefore both are parts of the economy’s supply side, perhaps consumption could be increased to 80 percent of GDP, and investment reduced to 20 percent, and production growth would continue as before? But this is entirely false.

If consumption were increased from 67 percent of GDP to 80 percent, and total GDP remained the same, then certainly total demand would remain the same—because both consumption and investment are sources of demand. Total demand would remain the same, and simply its division between consumption and investment would change. But if investment were reduced from 33 percent of GDP to 20 percent, because consumption had been raised from 67 percent of the economy to 80 percent, then the inputs into production would have been radically reduced. And because inputs into production had been radically reduced then, other things remaining equal, the increase in GDP would be radically slowed. That is, consumption cannot substitute for investment in production, because consumption is not an input into production.

This is why, for clarity of thinking and policy making, it is necessary to entirely eliminate such statements as “consumption contributed 67 percent of GDP growth”—consumption always contributes zero percent of GDP increase. This confusion between the economy’s demand side and its supply side provided the economic rationale for the damaging consumer, that is demand side only, U.S. stimulus programs.

The aim is consumption, but the means is investment

But that argument is false. If a billion yuan is used to give consumer tokens for purchasing food, or a billion yuan is used to subsidize free or cheap travel for tourism, that is all used at once in consumption, but it does not increase the capacity of the economy to produce in the future. The food which is purchased, or the trips which are made for tourism, are not an input into production, and therefore do not produce anything—that is why they are consumption, not investment. But if a billion yuan is used to build a railway, or purchase machinery for manufacturing cars, then the productive capacity of the economy is increased—it will produce new goods and services in the future. This fact, that the contribution of consumption to an increase in production, will always be precisely zero, because consumption is not an input into production, is crucial for economic clarity.

Confusions over these elementary but crucial issues of economic theory as will be seen, determined the strategic failure of the U.S. stimulus packages. They rationalized the huge boost in consumption but no increase in supply and therefore are also crucial lessons for future stimulus packages for China in 2023.

Under what conditions can consumption increase supply?

First, if in any economic system there is spare capacity it is possible that increased demand resulting from increased consumption can result in extra supply to attempt fulfil this demand. But if there is no spare capacity then, until extra capacity is created by investment, there can be no increase in supply no matter what the increase in demand is. That is, there may be a physical constraint on increasing production. If there is an increase in consumer demand, but no ability in the short term to increase supply, what will be produced by the increase in demand is inflation, not an increase in production and GDP.

Second, for capitalist producers, if there is an increase in demand, it is not sufficient that there is unused capacity and therefore no physical constraint on increasing production. In a capitalist enterprise there will only be a meaningful increase in production if there is also an increase in profit—that is, there may be a profitability constraint on production if there is an increase in demand led by consumption even if spare capacity exists.

Why the U.S. stimulus package was a strategic failure

In the purely short term, obviously when the pandemic struck there was immediately a sharp fall in U.S. production—in the 2nd quarter of 2020 U.S. GDP was 9.6 percent below its level in the 4th quarter of 2019 prior to the pandemic. But U.S. recovery was rapid, in part because of the stimulus packages—by the 1st quarter of 2021 U.S. GDP had already regained its pre-pandemic level. But, as already analyzed, the U.S. stimulus packages were designed to be, and were, almost exclusively consumer focused. As a result, U.S. consumption, but not investment, continued to rise strongly even after the pre-pandemic level of GDP had been regained. By the 1st quarter of 2021 U.S. consumption was already $741 billion above its 4th quarter of 2019 level, and then it rose by a further $3,028 billion by the 4th quarter of 2022. In contrast U.S. net fixed investment rose by only $73 billion between the 4th quarter of 2019 and the 1st quarter of 2021. Then it actually fell by $166 billion by the 4th quarter of 2022—to finish $93 billion below its pre-pandemic levels.

This experience during the U.S. stimulus packages clearly illustrates the theoretical issue that increasing consumer demand does not automatically lead to an increase in productive capacity, in investment—substantially rising U.S. consumer demand did not lead to an increase in investment but was accompanied by investment failing even to increase by sufficient to replace capital depreciation.

Strategic consequences for the U.S. economy

The short-term destabilization of the global economy caused by the U.S. stimulus packages, is extremely striking. But it is only an extreme illustration of the damage done by confusion over the role of consumption in the economy—this confusion also affects long term growth. Clarifying this theoretical conclusion leads to immediate factual, and therefore testable, conclusions which further clarify the reasons for the damaging strategic effects of the almost entirely consumer-based U.S. stimulus packages.

The prediction from economic theory is that because consumption is not an input into production, and investment is, then other things being equal the greater the share of consumption in the economy, and therefore the lower the share of investment, then over anything other than the short term the slower will be economic growth. Equally because, by definition, investment is an input into production, then, other things being equal, the higher the percentage of investment in the economy the more rapid will be economic development. As will be seen analysis of the U.S. economy fully factually confirms these theoretical predictions. This allows the long term strategic, as well as short term, failure of the U.S. stimulus packages to be clearly understood.

The slowing of the U.S. economy

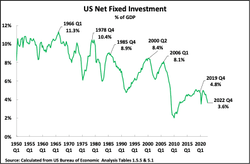

Over the short term no single structural factor of U.S. GDP has a decisive influence on U.S. economic growth—as analyzed below this means, for example, that a consumer stimulus can have a short-term effect. However, if longer time periods are considered then the situation is entirely different. Taking a 10-year period, as would be predicted by economic theory, there is a positive correlation, to be precise 0.66, between the share of net fixed investment in the U.S. economy and GDP growth—a very high correlation. That is, the higher the percentage share of net fixed investment in U.S. GDP the faster the rate of U.S. GDP growth.

For present purposes it is unnecessary to determine why there is this close positive long-term correlation between net fixed investment and U.S. GDP growth—although the obvious explanation, in line with economic theory, would be the positive cumulative effect of high levels of fixed investment, an input into the economy’s supply side, in increasing U.S. capital stock. Nor is it even necessary, for present purposes, to determine the direction of causation between high levels of net fixed investment and high levels of GDP growth, or even to ascertain whether some third process determines both. It is simply sufficient to note that, due to this high correlation, the U.S. economy cannot achieve high levels of GDP growth without there also being high levels of net fixed investment in GDP. In other words, if over the longer term the U.S. economy is to grow more rapidly the percentage of net fixed investment in the U.S. economy must increase.

This, therefore, provides the fundamental criteria for evaluating the strategic effect of the U.S. stimulus packages to deal with the consequences of COVID on longer term U.S. economic growth. As already noted, these failed to raise U.S. net fixed investment—on the contrary U.S. net fixed investment fell as a share of U.S. GDP during these stimulus programs. Figure 12 shows the declining levels of U.S. net fixed investment during successive post-World War II business cycles, which explains the long-term slowdown in the U.S. economy. As the latest stage in this decline, U.S. net fixed investment was 4.8 percent of GDP in the 4th quarter of 2019, on the eve of the pandemic. This had fallen to 3.6 percent of GDP by the 4th quarter of 2022. Given that the closest correlation for U.S. GDP growth is with net fixed investment the U.S. stimulus packages will therefore fail to raise the rate of U.S. long term economic growth—in line with IMF projections of a continuing slowdown of the U.S. economy. That is, the stimulus packages were accompanied by a further fall in U.S. net fixed investment—which in turn will undermine U.S. long term growth due to the close correlation of U.S. GDP growth and U.S. net fixed investment. That is these consumer-based packages not only produced extremely damaging short term inflation but were a strategic failure for the U.S. economy.

Negative effects on U.S. growth

It is therefore clear that the U.S. stimulus packages, because they were concentrated on consumption, produced no fundamental increase in the share of net fixed investment in U.S. GDP. Given that net fixed investment has the strongest correlation with U.S. GDP growth these U.S. stimulus packages therefore produced no increase in long term U.S. GDP growth. That is, they were a strategic failure.

The distinction between the percentage of consumption in GDP and the growth rate in consumption

As already noted, the long-term growth rate of consumption in the U.S. economy is highly positively correlated with overall economic growth in the U.S. economy. But as already show, the higher the percentage of consumption in U.S. GDP the slower is the rate of U.S. economic growth. Other things being equal, therefore, a higher share percentage share of consumption in GDP, by slowing economic growth, will lead to a slower growth rate of consumption. This prediction from basic economic theory, is confirmed by the fact that the negative correlation of the share of total consumption in U.S. GDP and the rate of growth of consumption is an extremely high -0.79. That is, the higher the share of consumption in U.S. GDP the more slowly consumption, and therefore U.S. living standards, grows. The same processes will be seen to operate in China’s economy.

But it is the level and rate of growth of consumption, not the percentage share of consumption in GDP, which affects people’s real lives. This is indeed obvious. For example, a country such as the Central African Republic has an extremely high percentage of consumption in GDP, 99 percent, but is one of the poorest countries in the world, with a per capita GDP of $492 and its per capita consumption has fallen by 15 percent in the last 10 years. It would be absurd to tell the inhabitants of the Central African Republic that they had a high level of consumption because it is 99 percent of GDP! What matters to them is their extremely low level of consumption, due to the very low level of per capita GDP, and the extraordinarily low rate of growth of consumption.

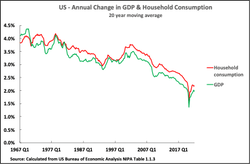

The correlation of GDP growth and consumption growth.

In contrast, there is almost a perfect long-term correlation between U.S. GDP growth and growth of household consumption as shown in Figure 13. Taking a 20-year moving average, to remove short-term effects of business cycles, the correlation between U.S. GDP growth and U.S. household consumption is 0.97—an extraordinarily high figure, leaving no doubt as to the extremely high interrelation between U.S. GDP growth and the growth rate of U.S. consumption.

In summary, an increase in the share of consumption in U.S. GDP will lead to a slower rate of increase of consumption, and a higher rate of growth of GDP will be associated with a higher rate of consumption growth. This basic prediction of economic theory is fully factually confirmed for the U.S. and, as will be seen below, equally applies to China.

Part 3. The Implications for China

First, regarding the position in the business cycle, the situation of China’s economy at the beginning of 2023 is significantly different to that of the U.S. when it launched its stimulus packages. In the 4th quarter of 2019, immediately before the pandemic struck, China’s annual growth rate was 6.0 percent. However, in the previous three years China’s annual average growth rate was 6.4 percent, and in the preceding five years it had been 6.6 percent. In short, when the pandemic struck China’s economy was growing significantly below trend—whereas when the pandemic struck the U.S. was growing significantly above trend. Furthermore, during the three years since the beginning of the pandemic China’s economy significantly slowed further—its annual average growth rate in 2020-2022 was only 4.3 percent. In summary China’s growth during the last period, before it launches any stimulus measures in 2023, has been significantly below trend.

In addition, the fact that whereas the U.S. experienced very high inflation China’s producer price index has actually been falling since October 2022, combined with China’s low rate of consumer price inflation, is entirely in line with China’s lower than trend rate of growth—indicating both an absence of substantial inflationary pressures and the existence of spare capacity.

Therefore, China’s economy as it enters 2023 is in almost the exact opposite situation in terms of position in the business cycle to the U.S. when it launched its COVID stimulus packages.

- The U.S. economy was growing above trend when it entered the pandemic and then launched a stimulus package overwhelmingly focused on the demand side—on consumption. As already noted, the result was predictable. With a large increase in demand, and no increase in net fixed investment, that is no increase in the supply of capital, the U.S. suffered extremely high inflation and low growth.

- China entered the pandemic growing below trend and its fixed investment, that is the supply of fixed capital, grew more rapidly than retail sales during the pandemic itself. China experienced more rapid growth than the U.S. and entirely escaped the inflationary wave in the U.S. China’s consumer price inflation in December was 1.8 percent and its peak inflation in that year was 2.8 percent, whereas U.S. consumer price inflation in December was 6.5 percent and its peak inflation during 2022 was 9.1 percent.

These changes in the U.S. and China were therefore both in line with economic theory. They also determine the different situations regarding economic stimulus programs. It is clear that in the short-term China has the economic space to launch a program containing a significant consumer, that is demand side only, stimulus without the likelihood of this creating major inflation. Indeed, a stimulus for consumption is necessary for both economic and political reasons. Politically, the relatively low rate of increase in consumption during the pandemic period, compared to its previous growth rates, means that a rapid short-term increase in consumption will aid the population in recovery from the sacrifices of the three —which saved millions of lives but involved sacrifices in living standards. Economically, consumer industries have been growing more slowly than their historic rate creating negative pressure on them. A stimulus to consumption would therefore greatly aid output in the consumer industries.

A boost to consumption is also particularly appropriate for a stimulus program aimed to have relatively rapid results—as, in general, short-term increases in production in consumer facing industries can be more rapid than in capital goods industries as consumer facing industries, in general, are less capital intensive than investment ones. Therefore, output can be increased in a shorter period without the very high capital expenditures frequently required in investment industries.

The forms of consumer stimulus

Certainly, the present author does not have personal experiences of economic stimulus in an economy the size of China, but nevertheless his experiences in a very large city economy, London, are relevant. The author was in charge of London’s economic policy from 2000-2008 and London’s economy is larger than that of the majority of European countries—due to its extremely high level of productivity, with it being the only city in Europe that equals U.S. levels of per capita GDP. The author’s experience was entirely in line with the experience of Chinese regions that have launched steps to stimulate short term consumption via marketing, price reductions, coupons, and other steps. The most powerful specific experience of such consumer stimulus programs in London was in 2003 when the city suffered an extremely severe external economic shock due to the consequences of the U.S. invasion of Iraq. This invasion, as with COVID, was an extraneous blow, that is not due to normal economic processes in the business cycle.

London is one of the world’s largest internationally oriented city economies—in particular, one of the world’s most important financial centers and largest travel destinations for both business and tourism, and these form a large part of its economy. Fear of terrorism or military attacks during the Iraq war led to an extremely severe collapse of international, and to a lesser extent domestic, visitors. An indicator of the scale of this was that under this impact of the war the daily price of hotel rooms in London fell by 70-80 percent and those locations which, for branding reasons, refused to reduce their prices suffered 70-80 percent falls in visitors. Visits by domestic visitors also declined due to fear of terrorist attacks. This created serious downward pressure on London’s economy.

To meet this crisis no stimulus package was launched during the war itself, as no price or marketing incentive would lead to people travelling or going to visitor attractions if they believed they might be killed. But a stimulus package was prepared in advance for when the war ended. As soon as that occurred a consumer facing stimulus package was launched by London’s city government essentially similar to that launched by some Chinese regions and cities at the beginning of this year. This consisted of two elements. First, a major marketing campaign, financed by the city government, was launched promoting visitor attractions, restaurants, exhibitions etc. in the city. Second, in an interrelated move, subsidies were launched to allow temporary price reductions to visitor attractions, restaurants, exhibitions etc. In the case of London, the private sector companies involved in this were encouraged to offer temporary price reductions and the city government also gave a subsidy to such companies to make the price reductions still greater.

The results of this consumer facing program were extremely successful. Both international and domestic visitor numbers recovered extremely rapidly boosting economic recovery in the city. It is entirely possible some of this stimulus may have leaked into saving, but overall it is clear that the majority was used for consumption and the overall short term program was successful. Therefore, for both theoretical reasons and those of practical experience the present author is a strong supporter of launching consumer-oriented stimulus packages in the appropriate economic circumstances.

But as already analyzed any such consumer stimulus, that is one purely on the demand side, does not automatically increase supply. Therefore, except in conditions of deep economic depression, with enormous amounts of unused capacity, which does not exist in China at present, a purely consumer, that is demand side, stimulus will, outside of the short term, lead to putting back to use large amounts of spare capacity but only an increase in the supply side, which involves increased fixed investment, can sustain over the medium/long term an increase in production/GDP. Therefore, to judge the strategic effect of any stimulus program it is necessary to constantly measure not only the short-term effects on demand and consumption but also to see if it is producing an increase in investment.

Longer term growth

First, other things being equal, what is being achieved by such consumer-oriented programs is to change in time when expenditure occurs—for example, this is achieved by a price and/or advertising incentive given for consumers to spend now and not to delay in time expenditure. But while experience shows this can have a significant short-term impact nevertheless over the medium/long term, if nothing else changes, expenditure will remain limited by income. The consumer stimulus may change in time the point at which expenditure takes place, which in some circumstances is extremely economically useful, but by its direct effect it cannot by itself alter the overall expenditure that takes place over time. Long term expenditure is determined by income. If everything else stays the same higher expenditure than normal in the short term will be accompanied by lower expenditure than normal later. Only an increase in income can create, other things being equal, an overall long-term increase in consumption. And such long-term increases in income are determined by economic growth and production.

Second, in anything other than the short term, that is while unused capacity is being put back to work, only an increase in investment, that is in supply, can increase output. If this does not occur then, as with the U.S. stimulus packages, the increase in demand from increased consumption will primarily, or even exclusively, over the medium/longer term produce inflation, not an increase in output.

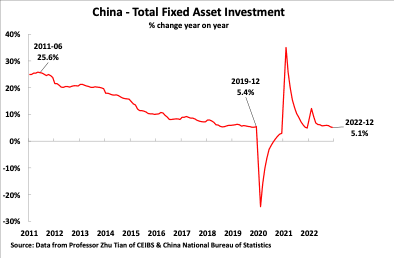

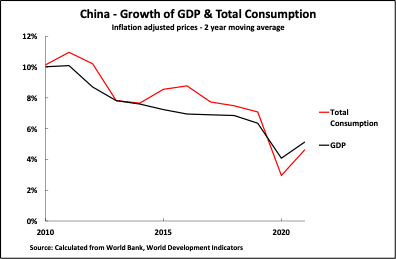

It is on this point that there is a clear medium/long term issue in China’s economy, and therefore for its strategy, which differs significantly from the short term. While China’s fixed investment has grown more rapidly than consumption during the pandemic this is exclusively due to the extremely sharp fall in consumption’s growth rate—it is not at all due to an increase in the growth rate of fixed asset investment. Figure 14 shows that the annual rate of increase of China’s fixed asset investment in December 2022, at 5.1 percent, was actually slightly slower than the 5.4 percent in December 2019 on the eve of the pandemic.

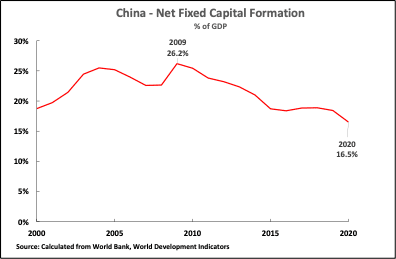

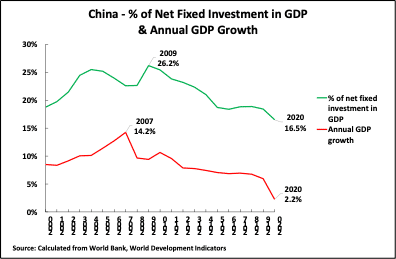

The fall in the proportion of net fixed investment in China’s GDP It is also crucial to note that over the longer term the percentage of fixed investment in China’s GDP, in particular net fixed investment, has fallen very considerably. Figure 15 show that between 2009 and 2020, the latest available internationally comparable data, the share of net fixed investment in China’s economy fell from 26.2 percent of GDP to 16.5 percent of GDP—a huge fall of almost 10 percent of GDP. |

| The percentage of net fixed investment in China’s GDP peaked in 2009 at 26.2 percent and fell by 2020, the latest available internationally comparable data, to 16.5 percent of GDP. Annual GDP growth peaked slightly earlier at 14.2 percent of GDP in 2007 and by 2020 had fallen to 2.2 percent—this last figure was certainly lowered by the COVID pandemic but the downward trend before this was clear. |

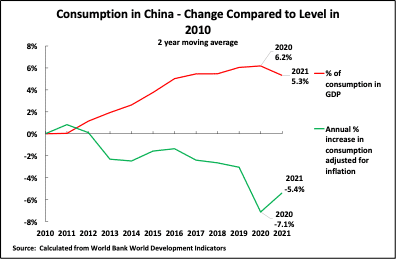

Confusion over the percentage of consumption in GDP and the rate of growth of consumption It is at this point that another theoretical confusion referred to previously comes in, again with exactly the same consequences as in the U.S. This is that loose talk of “increasing consumption” obscures the difference between the two different things of the percentage of consumption in GDP and the rate of growth of consumption. |

Because the percentage of consumption in GDP and the rate of growth of consumption move in opposite directions it is necessary to clearly strictly distinguish the two. This real relation is confused by unclear formulas of “raising consumption” as this obscures that an increase in the percentage of consumption in GDP will lead to a lower rate of growth of living standards. Therefore, to take the phrase in one recent article, talk of China having historically been “tightening its belt” because of its low percentage of consumption in GDP is highly misleading. It is the high level of investment in China’s economy which has led to a rapid rate of economic growth and therefore a rapid rate of growth of consumption and therefore of China’s living standards. “Loosening the belt,” if by that is meant a higher percentage of consumption in China’s GDP, other things being equal, will lead to a lower rate of growth of consumption and therefore a lower rate of growth in living standards—and therefore, over time, to lower living standards than are possible with a lower percentage of consumption, and higher level of investment, in GDP.

Relation of GDP growth a consumption The reason why increasing the percentage of consumption in GDP will lead in China to a slower rate of growth of consumption, and therefore of living standards, precisely as in the U.S., is because of the close correlation of GDP growth with the growth of consumption—as shown in Figure 18. The correlation is 0.76. |

In regard to this, certainly various predictions, theoretical or factual, may be made but, as always, in the end “the proof of the pudding is in the eating.” If there is not an increase in investment created by the demand created by the consumer stimulus program, which is precisely what occurred in the U.S., then all that a prolonged consumer stimulus will create, once unused capacity is put back to work, is inflation—again this is what factually occurred in the U.S. and was entirely in line with economic theory. To achieve the strategic goals for 2035, doubling GDP/per capita GDP compared to 2020, which requires a doubling of the economy’s productive capacity, then a very large increase in investment is required. An increase in consumption, because it is not an input into production, will itself create no increase in the economy’s productive capacity—despite the fact consumption is the ultimate goal of economic activity.

Incorrect statements, such as that consumption accounted for 67, or any other, per cent of GDP growth, as sometimes appear in sections of the Chinese media, obscure this reality and helped provide a rationale for damaging programs and results such as were seen in the U.S. in the last period. Investment will account for a large part of the increase in productive capacity which is required to achieve the 2035 strategic goals, consumption necessarily will be zero percent of the increase in productive capacity necessary to achieve the 2035 goals.

Finally. for clarity, these issues, naturally do not mean that even in the short term any initial demand side stimulus should consist wholly of consumption—demand for investment increases overall demand just as much as does consumption demand. But this difference of the demand and supply sides of the economy becomes particularly clear over the medium/long term. Therefore, increase in consumption demand, if unaccompanied by increased investment, can only produce relatively short-term increases in output. An increased in investment, in contrast, because it increases not only demand, but supply can lead to a medium/long increase in output and, therefore achievement of strategic goals.

The strategic goals in the economy, in particular, therefore require an examination of the conditions which will create a sustained increase in investment. That large issue, however, has to be the subject of another article simply for reasons of word length.

Conclusion

- As shown, confusion between the economy’s demand side and its supply side is extremely damaging. The facts regarding the results of the U.S. stimulus programs, and the issues involved for China, are entirely in line with both Marxist and serious Western economics. But they also show the dangerous errors of “vulgar” Western economics—errors which unfortunately sometimes appear in parts of China’s media.

- The negative aspects of the Western economies’ situation, the most severe stagflationary problems for forty years, was not caused by the Ukraine war—as this inflationary wave was already taking place long before that war started. It was directly caused by the major errors in the stimulus programs launched by the U.S. Frequently rationalized by the wrong idea that consumption can produce something, that is that it is an input into production, the U.S. launched a massive essentially exclusively consumer based, i.e., demand side only, stimulus. If such a stimulus had been launched when the U.S. had been growing below trend, and had spare capacity, then despite its theoretical confusions this stimulus package might have been effective—the impact of economic measures is determined by their practical content not by their theoretical economic rationale. But instead, this massive demand side only stimulus was launched when the U.S. economy was already growing above trend. The result was entirely predictable—with a huge increase in demand, and no increase in supply, the inevitable consequence was a huge inflationary wave, that is a short-term crisis. This inflation in turn led to sharply contractionary policies, notably steep interest rate rises, to attempt to bring it under control. These contractionary polices in turn slowed the economy—meaning that the stimulus packages were not only a short term but a complete strategic failure.

- China faces a sharply different practical situation. Its economy has been growing significantly below trend. A demand side stimulus will therefore find a situation where there is significant unused capacity. Under those circumstances a consumer stimulus, that is one solely on the demand side, is likely to be effective and necessary. Therefore, based both on considerations of economic theory and of personal practical experience, the present author strongly supports the idea of consumer stimulus as part of any overall stimulus program in China at present.

- A potential danger in China’s situation is of a different type. It is the confusion that appears in some sections of China’s media of repetition of the same confusions as in vulgar Western economic theory—the false idea that consumption is an input in production and therefore that consumption can produce something.

- The damaging practical consequences of this error are clear. A consumer-based stimulus launched in the current conditions of China’s economy, as already analyzed, should lead to a rapid and significant increase in production. But what will happen over the medium/long term will be determined by whether this demand side stimulus is accompanied by an increase in the economy’s supply side—which requires investment. The initial increase in output created by the consumer stimulus should not lead to damagingly high inflation in the short term for the reasons given, but after a certain period of time, exactly how long depends on how much spare capacity there is, unless there is an increase in investment, that is an increase in the supply side, there will either be slow growth, or inflation, or both—as in the U.S.

- The long-term implications for consumption of raising the percentage of consumption in GDP must be clearly understood. Other things being equal, over the medium/long term, the higher the percentage of consumption in GDP, because this lowers the percentage of investment, the lower will be the growth rate of the economy and of consumption. Over a longer period, such as the twelve years to 2035, increasing the percentage of consumption in GDP will lead to a lower level of consumption, and a lower standard of living, than with a higher percentage of investment, and therefore a lower percentage of consumption, in GDP. Those arguing for a higher percentage of consumption in GDP are in fact arguing in favor of a lower living standard by 2035 than would otherwise be the case. This is an inevitable consequence of the fact, demonstrated by economic theory, and confirmed factually by both the U.S. and China, that over anything other than the short term the percentage of consumption in GDP and the growth rate of consumption move in opposite directions—that is, the higher the percentage of consumption in GDP the lower will be the rate of growth of consumption.

- A consumption, that is purely demand side, stimulus is valuable in creating a rapid revival in 2023 by putting unused capacity back to work. But consumption, because it is not an input into production, can constitute nothing, that is precisely zero percent, of the doubling of productive capacity which is required to achieve the strategic goals to 2035. That doubling of productive capacity, however, requires a huge increase in investment. A necessary condition of the achievement of these strategic goals of 2035 is therefore creation of such investment—the conditions for achieving this, solely for reasons of space, requires another substantial article.

As the present global economic situation is largely defined by the by the extremely negative consequences of the U.S. stimulus programs, which was fully in line with economic theory, clarity on these issues is crucial both for achievement of China’s immediate economic targets in 2023 and the achievement of its strategic goals to 2035.

Author

John Ross is a senior fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He was formerly director of economic policy for the mayor of London.

Archives

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

Leave a Reply.

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

October 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

Categories

All

Aesthetics

Afghanistan

Althusser

American Civil War

American Socialism

American Socialism Travels

Anti Imperialism

Anti-Imperialism

Art

August Willich

Berlin Wall

Bolivia

Book Review

Brazil

Capitalism

Censorship

Chile

China

Chinese Philosophy Dialogue

Christianity

CIA

Class

Climate Change

COINTELPRO

Communism

Confucius

Cuba

Debunking Russiagate

Democracy

Democrats

DPRK

Eco Socialism

Ecuador

Egypt

Elections

Engels

Eurocommunism

Feminism

Frederick Douglass

Germany

Ghandi

Global Capitalism

Gramsci

History

Hunger

Immigration

Imperialism

Incarceration

Interview

Joe Biden

Labor

Labour

Lenin

Liberalism

Lincoln

Linke

Literature

Lula Da Silva

Malcolm X

Mao

Marx

Marxism

May Day

Media

Medicare For All

Mencius

Militarism

MKULTRA

Mozi

National Affairs

Nelson Mandela

Neoliberalism

New Left

News

Nina Turner

Novel

Palestine

Pandemic

Paris Commune

Pentagon

Peru Libre

Phillip-bonosky

Philosophy

Political-economy

Politics

Pol Pot

Proletarian

Putin

Race

Religion

Russia

Settlercolonialism

Slavery

Slavoj-zizek

Slavoj-zizek

Social-democracy

Socialism

South-africa

Soviet-union

Summer-2020-protests

Syria

Theory

The-weather-makers

Trump

Venezuela

War-on-drugs

Whatistobedone...now...likenow-now

Wilfrid-sellers

Worker-cooperatives

Xunzi

RSS Feed

RSS Feed