|

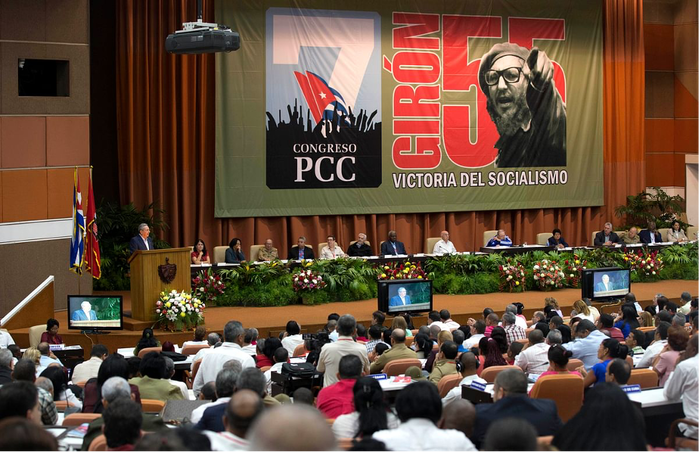

Marxist intellectual Antonio Gramsci developed the concept of cultural hegemony to explain social control by the ruling class. Cultural hegemony is when a ruling class transforms a society's beliefs, values, worldview, and definition of common sense to a form friendly to that ruling class. By accepting certain beliefs as self-evident truths, any divergence can be seen as utterly nonsensical. The notion that a person who starts a business, instead of the person who operates it, should deserve the entirety of the value produced by it is an example of a seemingly common sense value imposed through cultural hegemony. It remains unquestioned, yet unfounded. Certainly, the acceptance of self-evident truths can be a good thing but it's inherently a tool of control. These tools must be used for good, such as the belief that all people are created equal. Accepting that as common sense and a baseline worldview is a positive use of the cultural hegemony tool. Gramsci believed that this was an important tool and argued that labor intellectuals had to develop a labor ideology/worldview to replace the worldview of the ruling class. When observing the world with the knowledge of cultural hegemony’s coercions, one can begin to dismantle them. This takes us to the main topic of this article: the one-party state is more democratic than a multiparty liberal democracy. In the typical liberal democratic systems of the west (the United States inclusive), democracy is relegated through the election of politicians representing political parties. The crux of democracy isn’t on the exact politician as much as the party they represent. More so in the non-US systems, the exact member of parliament is mostly irrelevant as the overall point is to elect someone from the party of which they are a member. Therefore, the ability to affect social/governmental policy exists within the choice to vote for any political party. In a party-state, on the other hand, only one party appears on the ballot. Politicians representing just one ideology may be elected. How could this possibly be more democratic? First, the notion that democracy is tantamount to multiple political parties is an example of cultural hegemony. Democracy is defined as “rule of the people”, and political parties are a much more recent development compared to Athenian democracy. Political parties represent ideologies. On paper, this means that the successful formation of a government by a political party, or coalition of parties, is the people’s decision for the state to operate according to that ideology. However, while all multi-party systems nominally allow for any political parties to form and be elected, power is ultimately concentrated into the hands of a couple parties. The US, for instance, is officially multi-party, but the reality is that there are only two electable parties, thus, two ideologies to choose from. All ideologies do not have equal electability, even if they represent the greatest percentage of the population. (Many polls suggest a majority of Americans support social democracy but there exists no major social democratic party). Therefore, people in these systems only nominally have the ability to decide the ruling ideology of their state - the options are all predetermined. The ideologies that end up predominating are always capitalistic, as substantial capital is required to win elections and the capitalists are, of course, the ones with all the capital. Furthermore, because of cultural hegemony, the ideologies desired by people will tend towards the capitalistic. It’s hard to call something a “choice” if there exists mental manipulation beforehand. Because of the cognitive dissonance between lived experience of the masses and the “common sense” of capitalism, the majority tend to desire social democracy but often, not even that middle ground will be a realistic choice. Imagine, for a moment, a perfectly functioning parliamentary democracy where the desired ideology of the people is the ideology which the state will adapt. (Putting aside the major affront to the concept of a “free choice” that is manipulating people into accepting an artificial capitalist worldview.) While there is no such extant state, I will endeavor to prove how even this conceptual society is not inherently a democracy. From both a practical as well as a theoretical point of view, the multi-party liberal democratic system is not a democracy. First, choosing the state ideology does not mean people have the ability to directly choose policy. In general, specific laws, measures, and changes people wish to see are not proposed or voted on by the people. These are all done by the parliament/congress itself in which each MP/congressman/senator legislates according to an individual mandate. With an individual mandate, the elected official is granted a mandate by the constituency to act on its behalf, but the exact policies, laws, and all legislation is directly accountable to just themselves. The politician decides what to vote on, the politician decides what to draft, the politician decides everything. If the community bands together and requests a certain law be passed, their elected representative has no obligation to carry it out. Since the party of the individual politician is more relevant than the politician themselves, the mandate is usually towards a party line. Direct rule of the people does not exist. Here’s where some more cultural hegemony comes into play. We have accepted this status quo as a legitimate form of democracy despite it violating the most fundamental concept: rule of the people. At first, it seems ridiculous to suggest that this system isn’t democratic, despite a thorough analysis suggesting otherwise. Before continuing, I would like to add a disclaimer. When it comes to discussing socialist states, a monolith is usually constructed which makes it impossible to nuance their very different societies at very different times. For example, Stalin’s USSR was markedly different from Gorbachav’s, and both were completely different from China at any point in the last 70 years. I’ve discussed the inadequacies of the western multi-party system, but what about the party-state? In a typical Marxist-Leninist party-state, the party shares an important feature with the parties of the liberal democratic variety: it represents an ideology. In Marxist-Leninist states, the ruling ideology is not up for debate. While selecting ideology without directing the policy may not be enough to qualify as truly democratic, isn’t restricting that choice antithetical to democracy as well? Not at all. The free marketplace of ideologies can be disastrous and certain beliefs really shouldn’t be up for change. The belief that political views are “opinions” is objectionable. Politics has a tangible effect on everyone and some views are simply right or wrong. There isn’t such a thing as a “wrong” opinion but there is wrong politics. Morally, there is no issue with a state adhering to a specified ideology nor is this a blow to the quality of the democracy. Even in many parliamentary democracies, certain ideologies -like Nazi political parties- are outright banned due to their consequences. Of course, these countries do maintain a single, unchanging ideology. This is done through the cultural hegemony in which banning a political party is just one component. Cultural hegemony is a far-reaching process which goes well beyond the levers of control offered by any measly state institution. So, in a party-state, ideology is decided and cultural hegemony is placed solely in the hands of the state. Here is where it becomes democratic: all of the state institutions and policy is grass-roots. Because energy is taken away from a multitude of political parties and their limitedly varied ideologies, focus naturally falls to the policy. Policy in Marxist-Leninist states is in the hands of the people. Their elected officials, for the most part, do not have an individual mandate but an imperative or community mandate wherein direct democratic assemblies across neighborhoods and workplaces discuss their needs and desires and draft them into a plan which an elected official must work to achieve. These officials are called delegates as opposed to representatives to differentiate it from the liberal democratic system. Delegates are not elected for their ideology or capital investment into a campaign. Rather, they are elected based on their character and the community’s belief that they are the best person to deliver the action plan. These delegates go to either a national assembly or an intermediate council to share their community’s desires. In fact, the word soviet is Russian for council. Thus, “rule of the people” is respected. Again, socialist states are not a monolith. The level to which the party itself dictates policy varies greatly. For example, in 1930s Soviet Union, most substantial legislation and policy was dictated by the party. Local councils, or soviets, were called to administer the means of production in their area. Soviets were composed of delegates as described in the last paragraph. They had the authority to hire managers, plan out relevant public works, organize healthcare resources, hire doctors, teachers, and other essential workers. While there existed opportunities for the masses to contribute ideas to local legislation, a large part of the soviet’s role was implementing the policy dictated by the central party. The overarching policy was dictated by the state while the exact implementation was handled democratically through a deliberation between the soviets and the party. On the other end of the spectrum, consider today’s Cuba. Again, delegates are selected in the manner described before. These delegates go directly to the national assembly. The national assembly reserves 50% of its seats to these delegates. The rest are allocated to various mass organizations: trade unions, revolutionary defense committees, women’s organizations, etc. Unlike the USSR across any decade, the Cuban Communist Party is, officially and structurally, largely separated from these state institutions. Still, the party’s underlying ideology is constitutionally unchallengeable. The party maintains a presence within the mass organizations and deliberate with their members to form policy. Furthermore, new party members are generally sourced from within these mass organizations. Since the national assembly and the party are both sourced from the same pools, this gives the people two avenues for running their country: Via popular delegates at the national assembly and by selection into the party. Cuban democracy extends to many facets of life that the parliamentary form could never. For example, democracy is ingrained into the workplace. The same trade unions which elect delegates to the national assembly and comprise the party also select managers. Workers in a given factory vote on each prospective manager and may go through many until they find the right one. In a capitalist multi-party system, democracy is relegated just to a limited number of state institutions. While the level of policy participation may vary in a party-state, it remains clear that its fundamental structure allows for a great actualization of direct democratic control by the masses. Liberal democracy/parliamentary democracy, on the other hand, cannot. It simply doesn’t have the inherent capacity since it operates on an individual mandate. Granting a community mandate would make the political parties irrelevant and the system would cease. What is the purpose of having any party at all then? A directly democratic delegate model could function nonpartisan, right? Since a political party is defined by its ideology, the presence of a party serves to replace the cultural hegemony of the capitalist paradigm with a worldview and ideology favorable to labor. The specific form of mandate isn’t the only obstacle facing the parliamentary system as cultural hegemony goes far beyond state institutions. Without a party to dictate the new ideology, the previous cultural hegemony will remain even with the abolishment of political parties and the individual mandate. The “party-state” or “one-party-state” name might be a little bit of a misnomer. A few socialist states recognized the necessity of introducing other complimentary ideologies and worldviews for undoing social contradictions and allowed multiple parties to join them in governance (e.g., East Germany and modern China.) The fundamental difference between the party-state and the multiparty liberal democracy is really just the way cultural hegemony is enforced. In the latter, cultural hegemony happens through a variety of institutions both public and private. The illusion of choice exists with regards to ruling ideology, but it's limited through this coercion. In the former, a state is established which sets the ruling ideology and all institutions of control are managed democratically and deliberately between the state and the people. The party-states may have multiple parties. This allows for multiple ideologies to be endorsed. People in these societies may have the opportunity to effect real policy changes, granted it doesn’t interfere with the ruling ideology. (This is no worse than the presence of a constitution in most liberal democracies which can nullify legislation.) In a party-state, the economy, activities, creations, military, etc. are all fused with the state, as opposed to the current system where most of these aren’t even nominally accountable to public demands. This fusion allows for directly democratic policy making across all of these institutions. This combination of institutions with a state stokes a fear of authoritarianism - a rhetorical characterization ingrained by cultural hegemony. Of course this fusion gives the state more power, but what is the point of a democratic state if it doesn’t have the power to enact change to begin with? If people don’t have the means to exact their policy demands, democracy is a fantasy. Only with the party-state is this achievable. AuthorMy name is Jesse Jose Hernandez-Werbow. I am a Puerto Rican-american college student and a member of the PSL. A bit about my beliefs: I believe that the study of history is too unscientific and relies on rhetorical characterizations more often-than-not. The only proper way to understand history is through a clear, scientific methodology. This methodology was developed by Marx and utilized by some of the greatest philosophers since him. Further, Marx, Lenin, and Stalin developed scientific methodologies for all sorts of topics, including the science of revolution, the science of socialism/Marxian economics, and the study of imperialism: the greatest real-world contradiction. Through these methodologies, we can better understand the world around us and how to improve it. Archives August 2022

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed