|

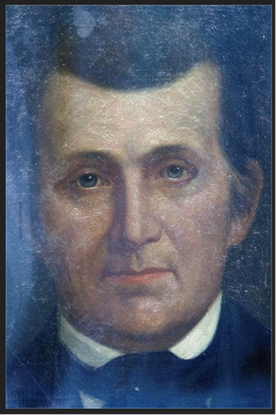

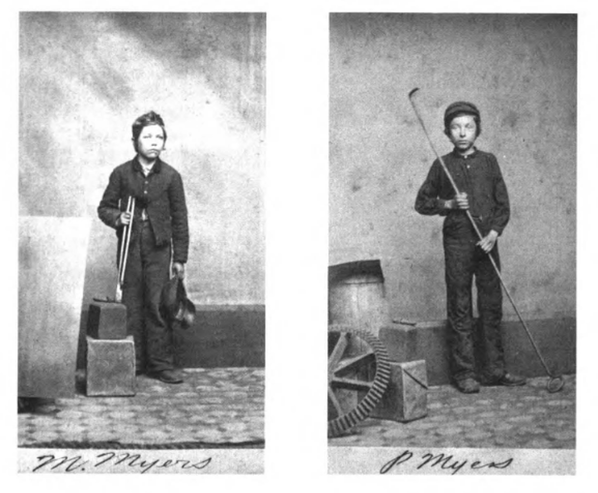

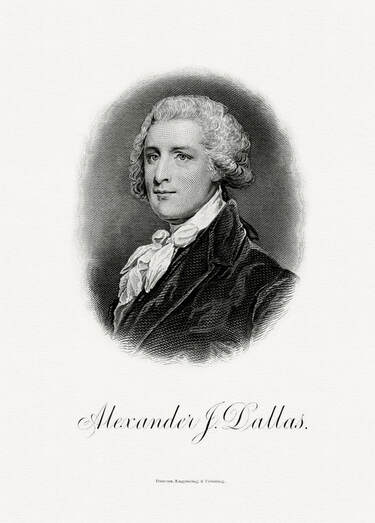

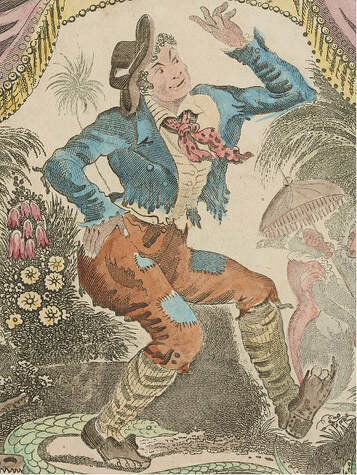

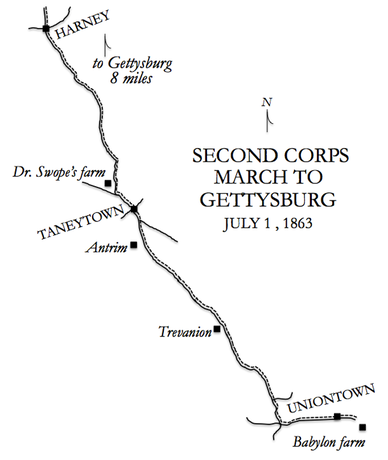

Ghosts of Plum Run is a leftist historical fiction series about the charge of the First Minnesota at Gettysburg. Tim is currently writing Volume 3 ~ Light, coming out in January, 2022, from which Midwestern Marx publishes the excerpt below. ”You look lovely ...,” Corporal Peter Marks muttered in his sleep, “...in purple...,” head turning back and forth on his haversack in the tent on Babylon Farm a mile east of Uniontown, MD, about 4:30 am., Wednesday, July 1, 1863. His tent mate, Private Rasselas Mowry, was sick of hearing Marks talk to himself. “We know, we know,” Mowry said, packing up for a day’s march ahead. To wake Marks, Mowry yanked the haversack out from under his head, dumping its contents onto his chest, including Millie’s purple handkerchief. Marks still murmuring, Mowry hit Marks with a slap from the purple hanky across his face. “Hey! We’re marching soon!” Marks rubbed his eyes. “Where’s my saber?” Marks mumbled into the ground. “In St. Paul where you left it in pieces two years ago,” Mowry laughed. “You remember nothing, do you...get up!” Marks stirred. A hangover announced itself like a knife through his head. He began trying to piece together where he was. “Were we at a dance last night?” Marks asked. “Ha ha!” Mowry chuckled, “you thought you were! Here, drink some water.” Marks propped himself onto his elbow to chug down half his canteen in one go. Then he fell back to the ground. “Coffee,” Marks moaned. Mowry grabbed a tin cup jumping out of the tent to Company A’s campfire, learning there from woozy half dressed comrades the march was delayed. Breakfast could proceed calmly. Thus began the First Minnesota’s 20 mile march to immortality the next day at Gettysburg, interrupted by frustrating stops and starts punctuated each time by the attendant urgency to brew coffee for hangovers. At one of those coffee brewing stops, two and a half miles north, a lady couldn’t sleep in her abandoned mansion, called Trevanion. Louisa Shorb was born in 1824 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Elizabeth Mark Shorb and Anthony Shorb, Jr., a grandson of John Shorb, who came to America with his two brothers from the Catholic Alsace Lorraine region bordering France and Germany. They arrived in Philadelphia on two ships, one called the Priscilla in 1749, the other called the Halifax in 1754, settling in Hanover, Pennsylvania, just a few miles across the Maryland border from where Louisa was losing sleep at Trevanion over a century later. The three Shorb patriarchs were typical of the German immigrant wave that would become known as the Pennsylvania Dutch, farming the land at first, then starting businesses, the succeeding generations restless and thinking bigger. Iron ore and coal deposits in central Pennsylvania formed the backbone of industrial capitalism not long after the Shorbs arrived from Germany, so that’s where Anthony went. After service in the army during the War of 1812, Anthony realized that being Catholic, like his ancestors, wasn’t good for business. So at 27 years old in 1815, Anthony married 18 year old Elizabeth at a church combining Lutheran and Reformed congregations, the Tabor First Reformed Church in Lebanon, PA, built in 1792, where services were said in German every two weeks. By the time their second daughter Louisa was 4 years old in 1828, Anthony was co-owner of one of the largest ironworks companies in America, Lyon & Shorb Co. of Pittsburgh, a sprawling empire of mines, boats, furnaces and forests. Three generations removed from his family’s arrival in America, Anthony Shorb Jr. rose to such power, the town where he first began working in iron, Tyrone, PA, was first known as Shorbsville. Anthony Shorb, Jr. Child laborers at Lyon & Shorb Ironworks Little Louisa thus grew up in Pittsburgh a very pampered, pretty princess. Her mother Elizabeth dutifully kept the home of an iron baron, bearing him three daughters. The girls loved traveling with their mother to visit the old uncles and aunts back in Littlestown near Hanover, or to her father’s partner, Mr. Lyon’s towering mansion called The Cedars in Tyrone, made of pure limestone nestled in the central Pennsylvania hills. When Louisa learned around age 10 that little boys her age made up much of daddy’s workforce, it didn’t bother her much, because as it turned out, she didn’t particularly like boys anyway. Louisa excelled in all the ladylike matters, loved art and music, always punctual and polite, a precious darling of a girl. Courting disinterested her as Louisa grew to a teenager, but her father, ever on the lookout for more ways to get more rich, had long ago begun seeking the perfect family into which to marry his daughter, which was duly accomplished when at age 20, Louisa Shorb became Louisa S. Dallas, her maiden name reduced to nothing but a middle initial in 1844 by an heir to a slave fortune. William W. Dallas, was born in Pittsburgh in 1823 into more and better placed generations of landed gentry privilege than Louisa; a long line of imperial colonizing British, then American, slavers. His great grandfather Dr. Robert Dallas first brought the Scottish family name across the sea to Jamaica around 1730. There, the good doctor accumulated 91 slaves on 900 acres, then began breeding, like a bull out to stud, at a castle named after himself. One of Dr. Dallas’s illegitimate children born of the slave women he impregnated he named Robert Charles Dallas, who settled into his inherited slave wealth as a man of letters, writing many books about the Caribbean wars fought to expand slavery, and also a lovely book about the poet Lord Byron. Robert Charles mortgaged the entire slave plantation into a trust for the benefit of the family heirs, one of whom was his brother Alexander J. Dallas, William’s grandfather, born on the Jamaican slave plantation in 1759. The Welsh name “Trevanion” first enters the Dallas family by way of Alexander’s wife, William’s grandmother Arabella Maria Smith, a great great granddaughter of Sir Nicholas Trevanion of the Royal Navy, who helped settle Newfoundland, in Canada. Alexander and Arabella married in England while Alexander studied law, then moved back to the family’s slave plantation in Jamaica in 1781 where Dr. Dallas arranged for his son to be admitted to practice law in the courts of His Majesty King George III. Sadly, tropical climes did not agree with Alexander’s delicate flower Arabella’s Welsh constitution, so the newlyweds moved to Philadelphia in 1783, the year America won independence. There, Alexander cobbled together a rather common racket of the time - government printing contracts. While living off his slave built trust fund, Alexander got himself admitted to practice law in Pennsylvania in 1785, then began printing Pennsylvania and U.S. Supreme Court decisions using his own slave money, the very first court reporting in America. Of course, being a slaver having never actually worked a day in his life, Alexander’s four volumes of court reporting between 1790 and 1806 were riddled with errors, inaccuracies and incompletions, reporting decisions so late one very important early case, Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), had already prompted the 11th Amendment to the Constitution voiding the ruling by the time Alexander reported it five years later. America’s first court reporter In Chisholm, the Supreme Court ruled states could be sued in federal court by individuals. Alexander Dallas immediately understood Chisholm as a deep threat to slavery, as practically all American jurisprudence would prove to be in one way or another for the next 70 years. So, being the only court reporter in America, Dallas duly sat on the Chisholm decision those five years to keep anyone with any power from reading it, creating a void of information in which states could swiftly ratify the 11th Amendment granting constitutional immunity to states in federal court, no one the wiser. As with every early American slaver, it all propelled William W. Dallas’s grandfather Alexander to his next act failing upward, the towering heights of American government as President James Madison’s Secretary of the Treasury from 1814 to 1816, during which he double dipped as acting Secretary of War in 1815. Into these generational layers of slave built privilege was born to America’s first court reporter William’s father, Trevanion Barlow Dallas, in 1801. Trevanion’s older brother George, born in 1792, would stay in Philadelphia to become mayor in 1828, climbing the slaver’s preferred route to power through the Democratic Party all the way to Vice President under James K. Polk in 1845. Trevanion Barlow studied law at Princeton until 1820, then followed another landed gentry slaver heir’s career path of the time - going west, to Pittsburgh. There, in 1822, he married William’s mother, Jane Stevenson Wilkins, born in 1802 to yet another powerful family, daughter of John Wilkins, Jr., who George Washington appointed as Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army from 1796 to 1802. Wilkins then became president of the Bank of Pennsylvania’s Pittsburgh branch. Banker’s daughter and slaver’s son in no time were centers of Pittsburgh high society by the time their first born son, William W. Dallas arrived in 1823. The trust fund in Jamaica kept William’s childhood just as comfortable as child labor produced iron kept Louisa, while both daddies climbed the ladder in Pittsburgh. Cultured as any ambitious aristocratic family would be, the Dallas family especially loved to hob nob with Pittsburgh’s leading music publishers, the William Smalling Peters family, who were the first to publish the sheet music to Thomas D. Rice’s foundation of black face minstrelsy Jump Jim Crow in 1831, when William was 8 years old. Thus, as a little kid in black face, William grew up dancing to America’s first popular music. By 18 years old in 1841, William’s father had became a prominent county judge in what was then the very wild west boomtown of Pittsburgh, population about 30,000. Looking west, as slavers always did, Judge Dallas’s musical friends the Peters family had become partners in a syndicate granted permission in 1841 to settle northern tracts of a brand new country, a breakaway portion of Mexico dedicated to defying Mexico’s attempt to end slavery, calling itself the Republic of Texas. Judge Dallas’s friends called their slice of this new country the Peters Colony. When Judge Dallas died unexpectedly that April, his bereaved slaver friends honored him by renaming their Peters Colony, built on the money of black face minstrelsy for the sole purpose of expanding slavery, Dallas, Texas. Thomas D. Rice as Jump Jim Crow, c. 1836 Louisa’s iron baron father had been seeking to arrange this very convenient marriage well before William’s very useful father, the judge, kicked the bucket in 1841. Sadly, neither was attracted to the other before William’s father died, because neither was attracted to the opposite sex, at all. What attracted them both after Judge Dallas’s death was money and power. One summer between William’s law studies at Princeton, they finally met at a minstrelsy show in Pittsburgh in 1843. A particularly rousing rendition of Jump Jim Crow set the crowd to dancing, so the two awkwardly joined in for appearances’ sake. When Louisa learned that night William’s family not only had political power reaching to the very pinnacle of American government, but also a trust fund his dear departed daddy had left him, the question was settled, and they wed in 1844 before William returned to Princeton. The marriage was never consummated. Instead, William finished his law studies, then sulked. After three years of unconsummated marriage, William wondering what he’d gotten himself into, he traveled to Europe in 1847 to find his bliss, whatever it might be, staying over a year. It was then Louisa knew her marriage was a lie. Thanks to his trip to Europe, William already knew it. Trevanion today They bought Trevanion in 1854, a 200 acre plot home to a very successful grist mill and distillery straddling Big Pipe Creek just northwest of Uniontown, first built in the 1790s by local Germans the Kephart family. David Kephart Jr. expanded the business in 1817, naming it Brick Mills. George Kephart sold to Dallas, who re-named it after his father, then pumped his and his wife’s trust fund wealth into the existing mill business to become a leading aristocrat in western Maryland as quickly as possible. The first thing William did was buy four slaves. The second, William needed the house to become a mansion, so hired one of Louisa’s cousins, architect and carpenter Joshua Shorb, to transform his home with the Parisian and Italian architecture William fell in love with while searching for his bliss in Europe. Mr. and Mrs. Dallas were immediate sensations in Carroll County, the housewarming ball upon completion of the new mansion the event of the decade, not just in Carroll County, but across the border in Pennsylvania. William tossed money around for a local railroad extension, to sit on boards, for charities, the works. Word went out among slave owning glitterati everywhere that a new socialite couple held the finest affairs at Trevanion, burst to overflowing with gowns and top hats. Costume balls, New Years Eve, the first day of summer, afternoon teas, Sunday brunches for the dozen or so house guests who couldn’t make it to their carriage the night before, any occasion at all, the lord and lady of Trevanion kept Western Maryland begging for more, delighting in plantation gallantry constantly. For a few years, the lie of their marriage, and the looming civil war over the slaves they owned, seemed not to matter to Mr. and Mrs. Dallas. It didn’t last long. On the morning of July 1, 1863, Louisa was alone, her husband gone, the world around her crumbling, armies surrounded her cavernous home now filled with cobwebs, her (now) five slaves the only people in the empty mansion. Her husband had deeded it all to her a year ago, and was somewhere else, Louisa knew not where. She spent that year alone questioning, searching, poring through his papers and diaries, especially those he wrote in Europe from 1847 to 1848, learning only that her worst fears weren’t nearly adequate. Louisa got out of bed that day for the final great event of Trevanion’s short life - to watch the Union Army march by on its way to Gettysburg. Two and a half miles south of Trevanion, the Second Corps was supposed to begin marching from Uniontown before dawn July 1, but the whisky soaked night before, the paper on which marching orders arrived from headquarters ended up in a muddy wad at the bottom of a shoe. The two hours it took to get new orders kept that morning mercifully slow. Uniontown would get one last opportunity to celebrate the 11,000 men of Hancock’s Second Corps, this time on their way out under the rising sun Wednesday, through the little town they entered after sundown Monday night at the end of 33 miles marching. In between, Uniontown poured 36 hours of whisky and feasting onto them at Babylon Farm, throwing a fancy ball for their officers, as full a day of rest anyone could hope for. A bit too full for many. Being German, during the day of rest Corporal Peter Marks tried to moderate the whisky with lager brought to camp in barrels by the town’s Germans, a terrible mistake. None of the regiment had had so much as a sip of alcohol in months, or a year, and only when snuck into camp against orders. Some managed the whisky deluge better than others, as Private Mowry did, but mostly, livers in the Second Corps were sitting ducks. Especially those who needed the most rest, like Marks, his feet raw from marching, chaffed and covered in sores from wet boots plodding across streams. Marks spent June 30 alternately passed out in the tent, then sick to his stomach bent over the creek running through Babylon Farm, then refilled by the town folk with liquor. It was all a blur. “Go back to sleep,” Mowry said as Marks took a first sip of coffee from the tin cup. “I didn’t go to a ball in town?” Marks asked. “Only in your dreams,” Mowry said, tossing himself to the ground, “which you spoke of constantly while having them. When you were awake, you were very upset you weren’t invited.” “Please tell me I didn’t make a scene of any kind,” Marks begged. “Corporals are officers!’ you kept yelling, ha ha!” “Oh dear.” “I thought you Germans could handle your booze,” Mowry joked. Marks put down the coffee to sit up, the purple hanky falling from his chest to his lap. He struggled to stand, grabbed the hanky and the coffee, then wobbled out the tent flap to find the creek. Marks stumbled through Company A’s tents, strewn with men as disheveled as himself. Above, a setting, nearly full moon and pre dawn stars mingled with passing clouds, heat of a long summer day already looming. At the creek, Marks bent down to dip the purple hanky in the water, wringing it out over his head, wiping his face with it, and in the wet cloth before his bloodshot eyes, he saw Uncle Monty, remembering the night he first met Millie, in her purple dress. AuthorTim Russo is author of Ghosts of Plum Run, an ongoing historical fiction series about the charge of the First Minnesota at Gettysburg. Tim's career as an attorney and international relations professional took him to two years living in the former soviet republics, work in Eastern Europe, the West Bank & Gaza, and with the British Labour Party. Tim has had a role in nearly every election cycle in Ohio since 1988, including Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020. Tim ran for local office in Cleveland twice, earned his 1993 JD from Case Western Reserve University, and a 2017 masters in international relations from Cleveland State University where he earned his undergraduate degree in political science in 1989. Currently interested in the intersection between Gramscian cultural hegemony and Gandhian nonviolence, Tim is a lifelong Clevelander. Archives September 2021

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed