|

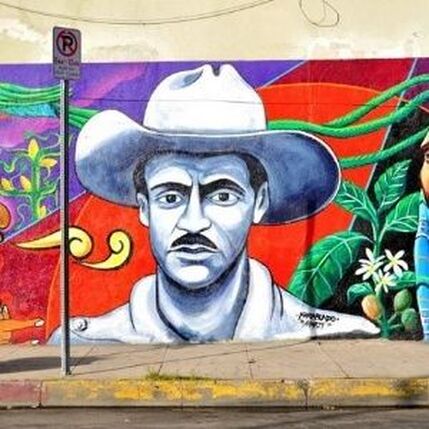

3/31/2023 Farabundo Martí: Father of Central American Communism. By: Ramiro Sebastián FúnezRead Now“When history cannot be written by the pen, then it must be written by the rifle.” - Farabundo Martí Introduction When you think of famous socialist historical figures, a handful of names usually come to mind. Karl Marx. Friedrich Engels. Vladimir Lenin. Joseph Stalin. Mao Zedong. These are the revolutionaries most commonly cited in the West. When it comes to famous socialist historical figures from Latin America, the known list gets even smaller. Fidel Castro, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, and Hugo Chávez are likely the three most well-known revolutionaries from the region. While all of the individuals named are worth studying — and in my opinion, are worthy of praise for their long standing service to the working class — there’s another little-known socialist revolutionary from Latin America who is just as important to learn about. An Indigenous man who founded one of the first communist parties in one of the smallest and poorest countries of Latin America. A proletarian internationalist, who traveled to Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Mexico, and the United States, to build a global communist movement. A humble campesino, who waged armed struggle against a national military dictatorship and a multinational agricultural corporation. This is the story of Agustín Farabundo Martí, the father of Central American communism. Life and Work Agustín Farabundo Martí was born on May 5, 1893, in Teotepeque, a small rural village in La Libertad, El Salvador. Martí shares the same birthday as Karl Marx, whom he would later take ideological inspiration from. He was born to parents Socorro Rodríguez and Pedro Martí, small coffee farmers who lived in extreme poverty. He was the sixth of fourteen brothers; five of whom died in their infancy due to a lack of resources and medicine. Martí grew up at a time when a rising multinational coffee oligarchy dispossessed Indigenous and peasant communities, using a U.S.-backed military dictatorship as its strongarm. He lived through extremely turbulent times, which began a few years prior to his birth, when land privatization laws were imposed in 1881 and 1882. Corporate coffee growers from abroad set up industrial factories in El Salvador and bankrupted thousands of independent small farmers. Most of these farmers were forced to become workers in the new businesses, selling their exploited labor as wage earners in the factories. Martí graduated from the Salesiano Santa Cecilia High School in Santa Tecla, near the capital city of San Salvador. Despite growing up in extreme poverty and illiteracy, he worked tirelessly to educate himself, graduating from high school with honors. He went on to study law at the University of El Salvador, where he was first introduced to the theoretical works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Ironically, it was also where Martí realized that the revolutionary theories of Marx and Engels shouldn’t be confined to urban bourgeois academics. Instead, they should be propagated among rural working class campesinos, who formed the majority of El Salvador’s population at the time. He fell in love with the ideas of national revolution and proletarian internationalism, dedicating the rest of his life to liberation of the working class. He dreamed of a socialist revolution across Central America, similar to the one which had just been constructed in the Soviet Union. In 1920, Martí was arrested for organizing a student protest against the right-wing dictatorship of Jorge Meléndez Ramírez and Alfonso Quiñónez Molina. Both of these individuals ruled the country with an iron fist, suppressing any and all worker-led uprisings against their capitalist policies, which generally served the interests of foreign multinational coffee companies. His arrest subsequently led to his exile from the country, and he took up residence in Guatemala and Mexico between 1920 and 1925. In Guatemala, Martí lived among the Indigenous Maya people of the rural Quiché region and the exploited workers of Guatemala City. He took up the most humble and varied trades to earn a living, such as bricklaying and farmwork. He was able to experience firsthand the exploitation suffered by Guatemalans under capitalism in both urban and rural environments. This was also a time of revolutionary activism in Guatemala, amid mass uprisings against the dictatorship of Manuel José Estrada Cabrera, a lackey of the United Fruit Company. Shortly after arriving in Guatemala in 1920, Martí traveled to neighboring Mexico, which was also rife with insurrection. The Mexican Revolution, during which armed groups successfully overthrew the dictatorship of General Porfirio Díaz, had just come to a close in 1920. The Revolution, led by Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa, resulted in the transformation of Mexico’s political system, aiming to create a more centralized, democratic, and populist government. Unfortunately, Zapata and Villa were assassinated, and many of the stated goals of the Mexican Revolution, such as nationwide land redistribution, never came to fruition. However, the radical ideas of the Mexican Revolution lived on for decades in the country; and many revolutionaries from abroad, like Martí, were deeply inspired by it. While in Mexico, Martí had a transformative political experience. He met with members of the Red Battalions, which were armed groups of the Casa del Obrero Mundial (The Home of the Global Worker). This workers’ organization subscribed to the ideology of anarcho-syndicalism, which views radical industrial unionism in urban areas as the only means by which to overthrow capitalism. This strand of anarchism is largely European in nature, and is hostile to both Marxism and organizing amongst the peasantry. As it turns out, Mexico’s Red Battalions were used by the reactionary forces of the Mexican government to fight against the revolutionary forces of Zapata and Villa. The Red Battalions were launched against the revolutionaries by the government of Venustiano Carranza, a wealthy landowner and politician. This, in exchange for concessions for the Casa del Obrero Mundial, which described Zapata and Villa as “peasant counter-revolutionaries.” These words mirror those used by Leon Trotsky in Russia and anarcho-syndicalists in China, to describe Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong, who successfully organized peasants for socialist revolution. Martí wrote unfavorably about these so-called Red Battalions, saying they were “deceived by the bourgeoisie” in numerous letters. This experience was crucial in his political formation. Not only did it solidify his orientation as a Marxist scientific socialist, understanding the need for building an organized communist movement of workers and peasants. It also helped him better understand the limits of anarchism and utopian socialism, which lend themselves to narrow-minded and short-sighted thinking. There were two other contemporary events that were pivotal in his political formation during his exile. The first event was the 1921 centennial anniversary of Central America’s independence from the Spanish Empire. On September 15, 1821, the modern-day nations of Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica proclaimed their freedom from the Spanish crown after centuries of colonization. From 1823 to 1841, the five nations were united as member states of the Federal Republic of Central America. The federation was led by Francisco Morazán of Honduras, who is considered to be the liberator of Central America from Spanish colonization. Morazán, the second and final President of the Central American Federation, fought tirelessly to maintain the integration of Central America. He understood that if Central America remained united, it would have a better chance of standing up to the rising threat of U.S. and British imperialism because of its key geopolitical position. Central America is the thinnest stretch of land between the world’s two largest oceans: the Atlantic and the Pacific. This unique aspect of geography is reflected in the blue and white stripes of most Central American flags. The region is also equidistant to both North and South America, allowing it to serve as a mediator of trade between both continents. Morazán was aware of the fact that Central America would maintain maritime and commercial dominance in the region if it were to stay united. Unfortunately, his dream of a united and prosperous Central America was crushed by the forces of empire. Morazán was murdered in battle against conservatives allied with the U.S. and the United Kingdom. The Federal Republic of Central America was dismantled into five separate nations. Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica were subjected to countless U.S. military invasions. And multinational corporations extracted endless wealth and resources from the region, making it the poorest part of continental Latin America today. In 1921, exactly a century after Central America liberated itself from Spanish colonization, Martí vowed to pick up the historic task set out by Morazán: to reunite Central America and build it up into a prosperous, sovereign, and multinational people’s democratic federation. The second contemporary event that was pivotal in Martí’s political development was the 1922 formation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. The roots of the USSR are grounded in the October Revolution of 1917. This was when the Bolsheviks, guided by the Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, overthrew the pro-Western Provisional Government that had previously replaced the Russian Empire. The October Revolution led to the creation of the Russian Soviet Republic, the world's first socialist nation. By 1922, following years of war against imperialist invaders and ultra-leftist traitors, the communists under Lenin emerged victorious, officially forming the Soviet Union. The USSR was a federation of fifteen national republics spanning eleven time zones, governed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The largest and one of the most populous countries in the world was now carrying out the revolutionary principles of Marxism-Leninism. Within a handful of years, the Soviet Union was able to lift millions of impoverished Eastern Europeans and Asians out of poverty, bringing political and economic power to the working class. To Martí, who was living on the other side of the planet, the idea of workers and peasants leading a successful revolution and building a proletarian state guided by Marxism-Leninism was very impressive. Especially considering the fact that the Soviet peoples were united, despite the dozens of religions, hundreds of languages, and thousands of miles that separated them. In his mind, there were important lessons to be drawn from the Soviet experience that could be adapted and applied to the conditions of El Salvador, and Central America overall. His revolutionary ideology transformed into a synthesis of Marx and Morazán: communism with Central American characteristics. His revolutionary activism was oriented toward building a united, socialist Central America. Upon returning to Guatemala from Mexico in 1925, he worked tirelessly to do just that. In 1925, Martí co-founded the Socialist Party of Central America in Guatemala City, along with representatives from El Salvador and Honduras. The organization later came to be known as the Communist Party of Central America, distinguishing itself from liberal and reformist social democratic groups that posed no real challenges to the ruling class. Although the Communist Party of Central America eventually broke off into smaller, country-based parties, they continued to work together well into the 1970s and 80s; decades that witnessed mass socialist uprisings in the region. A few months later, in 1925, Guatemalan General José María Orellana, then President of Guatemala, ordered a crackdown on foreign residents. Many of these were revolutionaries in exile, like Martí, who was arrested and expelled from the country. Martí was forced to take up residence, albeit for a short period of time, in nearby Nicaragua. It was in Nicaragua where Martí met a lifelong comrade with whom he would organize alongside for the rest of his life: the revolutionary anti-imperialist hero Augusto César Sandino. Sandino organized a guerrilla army in defense of workers, campesinos, and Indigenous peoples. Sandino’s forces fought against the U.S. Marines and their local lackeys who continually invaded and occupied Nicaragua, later serving as inspiration for the ruling Sandinista National Liberation Front. After spending no more than a few weeks in Nicaragua, but building a life-long friendship with Sandino, Martí returned to El Salvador to continue his revolutionary organizing at home. In 1925, Martí organized a local chapter of International Red Aid, a communist alternative to the Red Cross. International Red Aid was founded in 1922 by the Communist International to provide material and medical support for working class and oppressed peoples around the world. Martí worked closely with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, led at the time by comrade Joseph Stalin, who championed the national liberation struggles of the Global South. Through the local branch of International Red Aid, Martí was able to help other poor and underprivileged Salvadorans while also building a communist mass movement. From 1925 to early 1928, Martí joined the Regional Federation of Salvadoran Workers, a trade union center bringing together diverse sectors of El Salvador’s working class. As a leading organizer for the group, he was known for being a powerful agitator against the bosses and a compassionate companion to his comrades. Among the workers, he was affectionately called “El Negro Martí” (The Black Martí), because of his sun-tanned complexion. He would spend countless hours working alongside and organizing workers in the agricultural fields. He was also called “El Volcán” (The Volcano), according to a biography published by the Socialist Central American magazine. The magazine cites a comrade of Martí who once said of him: “He was like an indomitable volcano from whose bowels emerged red hot burning lava of heroic indignation against the local oligarchy, which crushes our people, and the brutality of imperialism, which fattens itself off of the bodies of the Latin American masses.” In the Spring of 1928, Martí traveled to New York City to represent Central America at the conference of the Anti-Imperialist League of the Americas. The League was an international mass organization of the Soviet-led Communist International established in 1925. Its purpose was to organize against U.S. and European imperialist intervention in Latin America and the Caribbean. William Z. Foster, the heroic Marxist-Leninist and Stalin-aligned leader of the CPUSA, played a key role in building international solidarity with Latin American communists like Martí. During Martí’s visit to the headquarters of the Anti-Imperialist League in New York City, police raided the building and arrested him, along with other comrades. During his arrest and short imprisonment in New York City, Martí experienced firsthand the racism, anti-communism, and viciousness of the Yankee state apparatus. He was eventually released and deported back to El Salvador. His return to El Salvador was brief and temporary. He used the time to prepare for his trip to Las Segovias, Nicaragua, along the border with neighboring Honduras, to join the guerrilla armies of his old friend, Sandino. A year earlier, in 1927, U.S. Marines descended upon and occupied most of Nicaragua, suppressing popular insurgencies against the right-wing government. By 1928, the U.S. had 2,000 well-armed troops in Nicaragua under the command of General Logan Feland. Sandino’s guerrilla army, despite being out-numbered and under-equipped, dealt the Marines numerous humiliating defeats. Not only did they have the backing of the predominantly peasant population. They also understood the mountainous terrain better than the foreigners, using its features to their advantage. While in Nicaragua, Martí organized a contingent of Salvadoran and Honduran communists, named “La Regional” (The Regional), to provide military and humanitarian aid to the Sandinista struggle against U.S. imperialism. In a public letter addressed from Sandino’s guerrilla camp, Martí wrote on June 22, 1928, that he had joined the Defensive Army for the National Sovereignty of Nicaragua, the official name of Sandino’s forces. The letter, directed at his comrades back in El Salvador, urged more people to come to Nicaragua and aid their brothers in the struggle for liberation. According to the testimony of General Carlos Quezada, the General Staff of Sandino's army, Martí was at the forefront of the armed struggle, never hesitating to go into battle. Quezada explained that one day, while Martí was writing on a typewriter, the U.S. Marine Corps Aviation forces were bombing the nearby army positions of the Sandinistas. As the bombing persisted, Martí put aside his typewriter and said his most famous quote aloud: “When history cannot be written with the pen, then it must be written with the gun.” Immediately afterwards, according to Quezada, he picked up a gun, took cover in a tree, and began shooting at the U.S. planes. For his distinguished participation in guerrilla movement, Martí was awarded with the official title of Colonel of the Defensive Army for the National Sovereignty of Nicaragua. Martí also served as Press Secretary and Head of International Relations for Sandino’s army. His international connections were crucial in building global solidarity for the Sandinista movement, arousing the attention of and support from socialist governments around the world. In 1929, during the height of Nicaragua’s military conflict, Martí assisted Sandino in clandestinely traveling to Mérida, Mexico, to seek aid for his guerrilla movement. Mexico, which had just experienced a nationwide revolution, was home to many socialists and communists sympathetic to Sandino’s cause. While in Mexico, Martí and Sandino stayed at the Gran Hotel in the city of Mérida, located on the Yucatán Peninsula. According to reports, they discussed their agreements, disagreements, dreams, political views, and their shared vision of a united Central America. Martí had planned to temporarily return to El Salvador to build more support for the guerrilla movement, and then go back to Nicaragua. Unfortunately, this would be the last time the two comrades see each other. Sandino, who went back to Nicaragua, was executed just a few years later after being captured by enemy forces. Martí headed for Mexico City, where he would remain until June of the following year, 1930, when he was expelled by the Mexican government for his revolutionary communist activities. When Martí returned to El Salvador in mid-1930, the country was embroiled in intensifying class conflict. Amid the crisis of world capitalism, known as The Great Depression, El Salvador experienced years of deepening misery. The international crisis caused a drop in the prices of coffee, a key export of El Salvador. Poverty increased in the countryside, banks went bankrupt, government revenues fell, and thousands of people became unemployed. Small farmers, indebted with loans and mortgages, were forced to default and handover their land to usurers and large landowners. This led to a greater concentration of land in the hands of a few wealthy foreign elites, who now hired back these small farmers as low-wage workers on their own lands. Meanwhile, El Salvador’s right-wing government issued two separate decrees in August and October of 1930 that banned all protests and meetings of workers, small farmers, and union leaders, labeling them as “communist agitators.” It also banned the printing and circulation of all workers’ publications, authorizing police to indefinitely detain anyone caught with what they described as “communist propaganda.” Amid growing poverty and state violence, Martí continued to organize the Salvadoran working class in their struggle for socialist revolution. Along with continuing his work for International Red Aid, he founded and directed the Communist Party of El Salvador, while playing a leading role in the Regional Federation of Salvadoran Workers. By the Fall of 1931, now at the age of 38, Martí returned to his roots and focused most of his organizing on defending the lands of small farmers, just like those of his parents. With the backing of International Red Aid and the Communist International, as well as broad support among the Salvadoran masses, El Salvador was on the heels of a major socialist uprising. On September 22, 1931, hundreds of Salvadoran farm workers defied the ban on protests and held a mass demonstration near San Salvador. They spoke out against a wealthy landowner and the inhumane work conditions on his hacienda. The landowner immediately called for detachments of local police and the National Guard, who, without warning, massacred the unarmed protesters. Fifteen workers were killed and 33 were seriously injured; many of them were women and children. Martí and his comrades immediately mobilized a protest in solidarity with the murdered workers, resulting in their imprisonment. They were released a few days later. In celebration of Martí’s release, large demonstrations were held in several towns across the country. Thousands of Salvadorans were out in the streets, expressing their solidarity with Martí and the Communist Party of El Salvador. Now Martí was on the Salvadoran government’s radar more than ever, especially because he had developed a mass following. According to news reports, Salvadoran President Arturo Araujo summoned Martí for a meeting. Araujo urged him to renounce his communist ideas and join the ranks of the liberal reformist Labor Party. He even went as far as offering him a post in his government. However, the conversation was fruitless. Martí laughed in his face, flatly rejected the deal, and vowed to intensify his revolutionary organizing. A few days later, Martí was detained and deported to Guatemala, where he stayed a few days. On December 2, 1931, nine months after the liberal president Araujo was inaugurated, he was overthrown in a U.S.-backed military coup. Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, a Salvadoran military officer and a leader of the far-right National Party of the Fatherland, became dictator of the country. He reigned as president for almost 12 years, during which time his fascist and anti-communist political party was the only legal one in the country. The military coup immediately generated a popular, indigenous, and peasant uprising, which culminated in January of 1932. Martí spearheaded the uprising, as the head of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of El Salvador. On January 22, the Salvadoran communists and Indigenous peasants of the Pipil nation waged an armed nationwide insurrection against the Salvadoran military dictatorship. According to historical records, over 70,000 rebels were involved in the uprising. The insurrectionists, led by Martí, liberated several cities across western El Salvador. Red flags adorned with the hammer and sickle were unfurled on numerous municipal buildings. The Communist Party of El Salvador was taking command of and redistributing key infrastructure. The Central American country was at the cusp of complete socialist revolution. Tragically, the uprising was ultimately crushed by the dictatorship. By January 24, the military dictatorship declared martial law and sent in the military to violently suppress the rebellion. Colonel Marcelino Galdámez sent hundreds of army units into the departments of Sonsonate and Ahuachapán, areas which are home to large Indigenous populations. On January 25, the military dictatorship began mass public executions and hangings of suspected insurrections, many of whom were Indigenous Pipils. Thousands were murdered in cold blood. In numerous villages across El Salvador, the entire male population was gathered in the town's center and killed by firing squads. The mass executions continued until February 1, when the dictatorship claimed that the region had been “pacified.” It was on this day, February 1, 1932, when Martí was assassinated on the direct orders of Martínez. He, along with some of his closest comrades, was shot to death in a town plaza. Martí was 38 years old. Between 10,000 to 40,000 people were killed as a result of the brutal crackdown, according to historians Joseph Tulchin and Gary Bland. John Beverly, another historian who specializes in Salvadoran history, provides evidence that around 30,000 people, or four percent of the country’s population, were killed by the government. As a result of the mass murders, which included the assasination of Martí, the historical event has come to be known as “La Matanza” (The Massacre). Martí’s anti-imperialist and communist vision was embraced decades later by new generations of young Salvadorans who fought against successive military dictatorships. In 1980, an alliance of five political parties and guerrilla movements joined forces and founded the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, known as the FMLN. The FMLN was an alliance of the Communist Party of El Salvador, the Farabundo Martí Popular Liberation Forces, the People's Revolutionary Army, the National Resistance, and the Revolutionary Party of Central American Workers. Throughout the 1980s, the FMLN heroically fought back against another right-wing military dictatorship backed by the United States under Ronald Reagan. By September of 1992, the FMLN transformed itself into a legal political party after the signing of the Chapultepec Peace Accords, which put an end to sixty years of military dictatorship in El Salvador. Conclusion Despite the brutal defeat of the peasant uprisings in the 1930s; despite the political shortcomings of the FMLN in the modern electoral era; the revolutionary legacy of Agustín Farabundo Martí lives on in the collective memory of working class people in El Salvador, Central America, and the entire Global South. Martí, the father of Central American communism, an Indigenous man who founded one of the first communist parties in one of the smallest and poorest countries of Latin America, is a revolutionary we can all draw inspiration from. AuthorRamiro Sebastián Fúnez is a Honduran anti-imperialist based in Los Angeles, California. Archives March 2023

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed