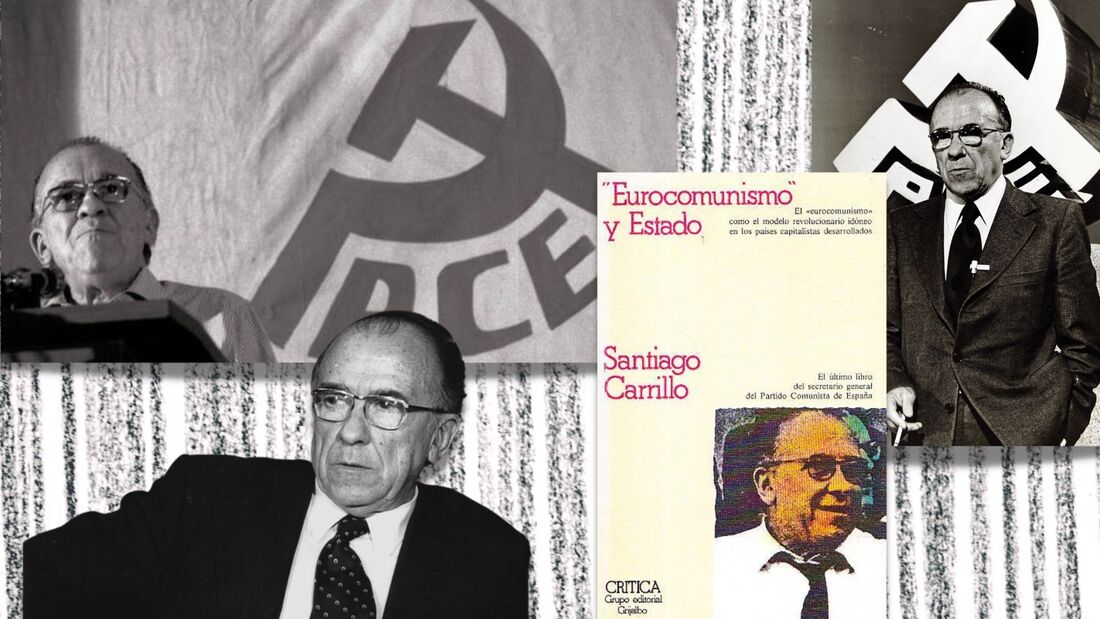

Chapter 5 “The Historical Roots of Eurocommunism”THE POPULAR FRONTS IN EUROPE AS ANTECEDENTS OF “EUROCOMUUNISM”POINT 1.) The following 10 points constitute the program of Eurocommunism. Although Eurocommunism is per se defunct, the CPs today adhering to similar ideas can be seen as inheritors of the Eurocommunist teachings. 1- Democracy is the Road to Socialism 2- A multi-party system 3- Parliaments and Representative Institutions 4- Universal Suffrage 5- Independent Unions (free of state or party control) 6- Freedom for the Opposition 7- Human Rights 8- Religious Freedom 9- Cultural, Scientific, and Artistic Freedom 10.Popular Participation in all the major forms off social activity This is combined with independence from any international centers [No more automatic echos of Soviet policies, or Chinese for that matter] These 10 points are domestic, there are also 7 international points which constitute the Eurocommunist versions of “proletarian internationalism.” 1- Cooperation and Peaceful Coexistence 2- No Military Blocks 3- No Foreign Military Bases 4- No Nuclear Weapons 5- Disarmament 6- Non-interference in the affairs of other countries 7- Self-determination for All Peoples These positions did not spring up overnight. They have roots going back to the days of the Popular Front but three major historical events have brought them to the forefront of Communist consciousness and discussion today [the 1970s] but even now they still reverberate: 1.-The 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union 2.- The invasion of Czechoslovakia (1968) 3- The Sino-Soviet Split The rest of this section is taken up by historical speculation on the part of Carrillo. In the political struggles of the 30s against fascism and Nazism, especially the Spanish Civil War and WW2, Carrillo was a major leader and knew most of the other Communist leaders. Behind the facade of a united Third International position on all the major issues, Carrillo points out the real internal disputes between the leadership of major Communist parties (the French, Spanish, Italian, British which wanted to tailor responses to fascism to their national features (to actually participate in Popular Front governments, or to remain outside of the government, for example.) The Third International (directed from Moscow) position always won out and for unity the national CPs went along. The French party did not join the popular front government for example. Well, the fascists were on a roll, came to power, wiped out the CPs public presence, they went underground and didn’t surface publicly until Germany was defeated by the USSR. Carrillo speculates that the fascists might have been halted if the Third International had not enforced its policies regardless of the different existential circumstances of the national CPs in Europe, etc. This is could’ve, would’ve, should’ve Marxism so I will skip it and go to the section where Carrillo was actually participating in one of these struggles — the struggle in Spain where he had first hand knowledge. THE SPANISH EXPERIENCE—THE CASE OF TROTSKYThis is Carrillo’s position in brief. When Spain became a Republic in the 1930s the CP was small and sectarian and following the line of the Communist International it proclaimed a class war against the bourgeoisie— this was class against class and no cooperation was allowed with the petty bourgeoisie or other classes— the workers would duke it out alone with the capitalists. The CP leaders however began to work with other left forces to broaden their appeal. These were pre-popular front days but there were changes under way in the International which facilitated these moves by the CP (this was 1933). Soon the Popular Front was the new International position and it was in full swing in Spain. The CP also included the Trotskyists into the Popular Front and in the Front’s government in Catalonia. This was non-sectarian at a time when communist parties around the world were fighting with Trotskyists. The collaboration did not last long, however, and the CP adopted the view of the International (the Soviet view) of Trotsky as an enemy of the Soviet Union. Now, in the 1970s, Carrillo said, the communists are talking about Trotsky and the Trotskyist role in the civil war again— a reevaluation seems in order. In the 1930s people were unjustly accused of being “fascist agents.” They are due for rehabilitation. Even nowadays in the 21st century there is much disinformation about this subject in circulation. In those days, Carrillo said, we Communists really believed that Trotsky and the Trotskyists were working for the fascists. A lot of this information was also being peddled by anti-communists as well. The Moscow trials and the confessions of the accused persuaded the CP, as well as others, of Trotsky’s guilt. But, Carrillo stresses, none of them in those days had any idea “of the infernal machine by means of which those confessions were obtained” [p.117] The victims of the Moscow trials and the Trotskyists proclaimed their innocence and the Trotskyists tried to expose the methods by which confessions were coerced but we chose to believe the Soviet Union. Fascism was on the rise. The Soviet Union was the first and only socialist state and Stalin was its leader. We had no first hand knowledge so, by “an act of faith,” we believed what the Soviets told them. So, “it was possible for the myth that Trotsky was linked with the Nazis and was protected by American imperialism to arise and establish itself, and we youngsters of that period swallowed the official accounts of the October Revolution and of the subsequent civil war, in which Trotsky’s role was passed over in silence.”[p.117] It is high time this myth be put to bed and an objective scientific account of Trotsky be written showing that Trotskyism was a trend within the Revolutionary Russian tradition instead of just treating it as some sort of pro-Nazi movement. Having said this, Carrillo notes “Trotsky’s opinions on the Spanish Revolution of 1936-39 could not have been more profoundly mistaken.”[p.118] This is because he looked at Spain through the lens of the Russian Revolution and its tactics ignoring the fact that Spanish conditions were totally unlike the conditions facing the Bolsheviks. Finally, the case of Andreu Nin is discussed. Andreu Nin was a Trotskyist leader of the POUM party during the Spanish civil war. He disappeared in questionable circumstances and it was alleged he defected to the fascists (Franco) or that he was murdered by the Communists depending on your views of the POUM. Carrillo said, after he did all he could to find out what happened, that Nin did not defect to the fascists and that he was indeed extra judicially murdered but that it was not done under the auspices of the CP —but members on their own may have been involved. The POUM was foiled in a coup attempt against the Republic during the civil war — this was an act of high treason but Nin should have had his day in court. THE SPANISH EXPERIENCE: THE POPULAR FRONTThe leadership of the Spanish Republic in the early 1930s was in the hands of the bourgeois liberals. There had been cooperation between the socialists and liberals from 1931 to 1933. In 1934 the liberals alone were running the show. A real fascist threat developed and the socialist led Popular Front declined to work with bourgeois elements (the liberals). Seeing this disunity the fascists began an uprising, a civil war that lasted three years and brought Franco to power. The Popular Front joined with liberals when they saw what was transpiring, but by then it was too late, the war was underway. Carrillo maintains that in the Republican held areas a unique sort of Popular Front came to be, unlike the other European Popular Fronts, and it foreshadowed the kind of new democracy that Carrillo thought must be transitional between bourgeois democracy and socialism which was the basis, later, for Eurocommunism. The closest analogy I can think of is that Carrillo’s Republican zones were practicing a sort of participatory democracy à la 1960s SDS style. “At that time we communists were already upholding the parliamentary democratic Republic, the representative bodies of the nationalities, which brought down on us a lot of criticism from leftists. Already at that time we thought that by maintaining these forms of representative democracy, by doing the same with the bodies of the nationalities, with local government bodies, and by developing forms of direct democracy in the factories and other enterprises, by giving the working people a direct say in the running of affairs at all levels, the foundations could be laid for a democracy of a new type which would proceed to socialism.” [p.123] He also quotes from a letter he got from Stalin et al “It is very possible that the parliamentary road may turn out to be a more effective procedure for revolutionary development in Spain than it was in Russia.”[p.124] Despite subsequent revelations about Stalin, this letter shows that many Communists were seriously thinking about the parliamentary road being sometimes possible and this view was also backed by the 20th Congress of the CP of the Soviet Union. It is perhaps impolitic to point out a little over 30 years after this Congress the parliamentary road more often resulted in CPs being voted out of power than into power. Here we might make a comment about the use of slates. Some CPs use slates to elect their leadership and claim this is what unions do. It is correct that unions opposed to democratic elections do this. This is what Carrillo says: “We communists always fought for the democratic election of factory committees, coming out against the unfortunately dominant attitudes which left the composition of those committees to nomination from above by the trade union bureaucracies.” [p. 126] It is really ingenuous to claim that the use of slates is a democratic procedure. Finally Carrillo concludes, “it is not only from a Marxist analysis of present-day reality, but also from our own complex experience, that we derive the arguments in favor of the democratic socialism we advocate for our country.”[p.129]. It isn’t too far off the mark to say that the arguments for Eurocommunism have not been fruitful. THE EUROPEAN COMMUNIST PARTIES AFTER THE SECOND WORLD WAR At the end of WWII the CPs were at the height of their power. They had played the leading roles in the various underground resistance movements to Hitler and the Soviet Union had played the major role in the defeat of Hitler. They participated in the governments of the newly freed Western Europeans governments Italy, France, and others) and they played by the rules of parliamentary democracy. They were so strong that had the Soviet Union told them to, they probably could have taken over these countries by force. The Soviet Union did not tell them to take power. Probably due to the Yalta agreement between Stalin and Truman. The Eastern European countries along the Soviet border occupied by the Red Army would become part of the Soviet sphere of influence, Western Europe of the American. Nevertheless, these CPs played by the rules of democracy by their own choices as well, even after 1947 when the Americans began the Cold War and the Communists were kicked out of the coalition governments. Carrillo says another factor at work was trying to get free from Soviet control. Stalin had dissolved the Third International at the beginning of WWII (to show good faith to the Americans as allies against Hitler). Without the International the other CPs were no longer bound to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Yet they felt a loyalty towards the first socialist state. In 1947, after the Cold War began, Stalin founded the Cominform (Communist and Workers Parties Information Bureau) which brought the CPs together again under the guidance of the CPSU. Democratic methods remained in force in the Western parties. This remained the case until 1956 when the Cominform was dissolved during the de-Stalinization process. The Communist Party Spain operated under the principle that in Spanish affairs they had the final say and it was in International affairs that they followed the Soviet Union. The SU often did things on their own without consulting the other members of the Cominform and the others all went along for fear of being “excommunicated.’’ An unforgivable error, according to Carrillo, was going along with the SU when it denounced Tito and condemned Yugoslavia when it showed signs of independence from Moscow. For the Spanish party the “culminating” point was the Soviet led Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. No prior consultation, just the SU announcing the invasion to prevent capitalist restoration (with no proof) using the same methods as in the 1936 Moscow trials and the condemnation Yugoslavia— I.e., lies, disinformation, and stories “that were light years away from the truth.” [p.132]. This is the background which led to Eurocommunism and a commitment to the peaceful democratic road to socialism and the independence of national CPs. Still, the Eurocommunists consider the Soviets comrades and fully support their struggle against US imperialism. THE ROLE OF VIOLENCE IN HISTORYCarrillo tells us that the long years of the struggle against fascism has made communists more appreciative of (bourgeois) democracy and to support it in capitalist regimes, and also aware of its weak and under-appreciated use in the socialist states. Nevertheless, communists will not abandon the revolutionary struggle to overthrow imperialism and capitalism throughout the world. It is not a struggle in this or that country but an international struggle to overcome the economic system of capitalism per se. Each country has its own struggle but we are all together in the hopes for this international elimination of the capitalist system. This is NOT a turn to social democracy and communists are not social democrats. We are not abandoning the possibility of a revolution. Should the capitalist block the democratic road to socialism and revolutionary alternatives appeared we would support the revolutionary overthrow of the capitalists. However in Spain and countries in similar circumstances, the Eurocommunists declare the conditions have already arrived by which the nonviolent democratic electoral road is possible and that is how we will proceed to socialism. [40 years later in the 2000s we will find Carrillo not only no longer in the Communist Party but also a social democrat. He died in his 90s in 2012. So far the “peaceful road to socialism” has always led to a similar destination but that doesn’t mean we won’t find a fork in the road that gets us where we want to go.] We are not turning our backs on the historic role of violence in history. Without the English Revolution (Cromwell), the American Revolution, the Great French Revolution, the wars of Napoleon, the bourgeoisie would never have been able to overthrow the feudal system and spread the capitalist system around the world and become the new ruling class. Political power did indeed grow from the barrel of a gun. As far as today is concerned, the example of the Paris Commune energized the working class and spread the ideas of working class democracy— and the fact that we today have such advanced democratic rights in many countries is due to the the response to the Russian Revolution and the defeat of Hitler and fascism for which the main credit goes to the Soviet Union and the Red Army which knocked out 80% of Hitler’s military and ended the possibility of a German victory in WWII. The violence of the past is responsible for all this. But, Carrillo believes, this has also brought about a qualitative change in history where violence is no longer necessary. [Well, the Soviet Union and the Red Army are history and fascism is making a comeback so perhaps Carrillo’s ‘qualitative change’ was just an illusion.] THE RUSSIAN COMMUNISTS HAD NO CHOICE IN 1917 BUT TO TAKE POWERCarrillo points out that Marx and Engels lived at a time when the working class was really only developed in parts of Western Europe and the U.S., England and France especially. Imperialism was just beginning (finance capital). Capitalism was fully developed and in its highest stages by the time of Lenin. Until WWI the three great international leaders of the working class were Marx, Engels, and then Kauksky. Kauksky’s Road to Power was the go to book for the revolutionary movement. The original “revisionist,” Bernstein had published his book also (Evolutionary Socialism) but it was “unorthodox.” The official theory was more or less as follows: Capitalism was going to fall apart due to internal contradictions after it had fully developed the productive forces to their maximum and this would happen in the most advanced capitalist countries where the class conscious Marxist workers would take over and begin the construction of socialism. The rigors of WWI brought about the collapse of capitalism in backwards Russia, socialism would be impossible there, what was needed was a bourgeois government that would bring Russia into the world of advanced capitalism before socialism would be possible. Socialists saw WWI coming and argued about the possibility of a revolution breaking out in countries as a result. The consensus was that if it did in a backwards area it could be successful because the revolution in the advanced countries would come to its aid. This is similar, e.g., to the Soviet Union coming to the aid of the Cuban Revolution which allowed it to survive the U.S. while it consolidated itself. This didn’t work in Afghanistan. The Bolsheviks were forced to take power in Russia because the country was falling apart and the provisional bourgeois government was totally incompetent. The Bolsheviks ended up isolated in a backward country and the revolution didn’t happen in the advanced countries. After waiting for the revolution for 10 years Stalin came to power and proclaimed “Socialism In One Country”— they tried for about 70 years but that whole system finally caved in. Neither the Eurocommunists nor the anti-Eurocommunists saw this coming. But Carrillo did see all the problems, as well as the good things, that ‘’Stalinism” brought about. Industrialization, economic development, scientific advance (Sputnik) but at the expense of democracy, free expression, and lower living standards than the West. His final views were that, for backward areas (underdeveloped) violent Revolution may be required and should be supported (Cuba, Vietnam, Laos, Korea, China) but in the advanced capitalist countries the road to power was the democratic parliamentary road towards a peaceful arrival at socialism. For all that, however, Carrillo says the Communists of today are the children of the great Russian Revolution and of the CPSU and the whole history of our movement. We are not Social Democrats who have always opposed the revolutionary forces and seek to merely reform, not do away with capitalist oppression and exploitation. Coming up next, the last chapter: Chapter Six THE DICTATORSHIP OF THE PROLETARIAT AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. He is the author of Reading the Classical Texts of Marxism.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed