|

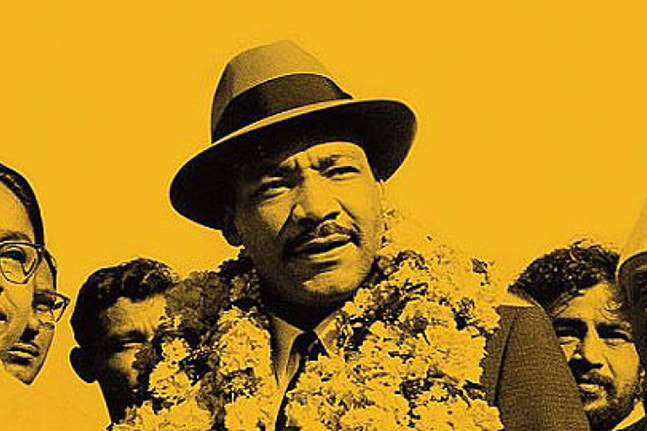

5/5/2022 Dialectics of the Afro-Indian Diaspora: Race, Caste, and the Struggle for Solidarity. Jymee C.Read NowNico Slate (2017), Colored Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom in the United States and India, Harvard University Press. 344 pages- $24.00 Global politics both before and during the Cold War era introduced a vast extension of diasporic connections and political development throughout the world, particularly in the context of the struggle of the non-white population. The inter-connection of black and Indian politics in this era of struggle ultimately constructed a path for solidarity in the Afro-Indian diaspora, alongside a dialectical display of the contradictions that accompany said solidarity. Nico Slate’s Colored Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom In the United States and India serves as an outlet into the such contradictions, in addition to the attempts at unity in the Afro-Indian diaspora. The complications in establishing links between caste, class, race, and nation in the Afro-Indian context provides a glimpse into the dialectical relations between the two, with the material conditions of the Cold War on both an international and a national scale playing an integral role in global diasporic endeavors. In line with efforts to build and uphold diasporic connections, the shift from slave society in the United States to the rise of imperialism serves as one of the primary catalysts in Afro-Indian internationalism. As the United States built an empire of economic, political, and cultural hegemonic control, there emerged the forging of a relationship between African-Americans and those on the lowest rung of Indian caste society. The dialectics of such a relation reflects in simultaneous fashion a sense of solidarity and a sense of division in such a diasporic structure. Though the prospect of a “vanguard of darker races” draws a promising connection in the struggle for global liberation, such a prospect is troubled by the hierarchical order of India, within both the caste system and the systematic understanding of race.[1] In the pursuit of anti-colonial, anti-imperialist, and anti-racist coalition, the issue of racial identity in particular plays a strong role in the complicating of the Afro-Indian diasporic structure. Whereas the color line in the United States and the established racial hierarchy was (and is) at least marginally more cut and dry, the racial structure of India establish issues for building solidarity. Though more affluent African-Americans utilized a religious justification for separation from lower-class blacks and what they considered to be “backwards societies,” Indians both in India and the United States played on the racial dynamics as created by then-contemporary ethnologists. Lower-caste Indians and African-Americans found common ground in their darker complexion, with the caste system reflecting a racial dynamic reflecting hierarchical distinctions. Those on the bottom rung of the caste system, essentially the Indian equivalent of the lumpen-proletariat, more often than not are of a darker complexion, and thus had been ascribed “negroid” characteristics, allowing for a stronger possibility of diasporic connection between the most disenfranchised masses of the two respecting countries. Indians in American and in India itself relied wholly on the intersection of race and caste to enforce notions of supremacy.[2] Building upon claims made by ethnologists at the time, those within the higher sects of the Indian caste system, effectively the bourgeoisie of the caste system, employed an identity of Aryan/Caucasian origin due to their lighter skin. These disparities in race and caste within India alone brought about a further complexity to the erecting of a powerful diasporic alliance. These disparities in understanding of race, caste, and nation witnessed a new advancement in the question of a “third world” and how such a dynamic development affected the Afro-Indian diaspora during the Cold War. As the Cold War raged on, so came an effort to establish an international opposition to global imperialism, racism, and colonialism, with renewed strength stemming from the rise in counters to western hegemony. Reflecting a colored cosmopolitanism, one championed by Indian activist Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, an anti-imperialist coalition within the Afro-Indian diaspora became apparent as a necessity to counter the spread of reactionary western cultural and racial superiority. To quote; “The Negro Problem will only cease when the color-line of imperialism vanishes.”[3] However, the establishing of such a coalition drew its own issues, with the liberalism of one Walter White providing numerous difficulties in establishing an Afro-Indian internationalism in trying to both appeal to a sense of Americanism, and battle the white supremacist structure of the western world. Walter White pushed for a colored cosmopolitanism that both recognized the injustice of American racism and British imperialism, while attempting to appeal to the upholding of western democracy. White played a particular role in this crusade due to his liberal anti-communist outlook, wanting to battle the structural foundation of American racism while actively avoiding any potential association with the Soviet Union in particular, and with affiliation with Communism itself being a focal point of White’s campaign. In an effort to simultaneously further build a transnational solidarity and acting in a liberal form of containment, White states in a letter to one J.J. Singh; “One of the reasons for the spread of communism in China and other parts of Asia is due in part to the lowered prestige of the United States and faith in democracy because of discrimination in America.”[4] Though many African-Americans indeed hoped to maintain a pro-western, Americanist disposition, one can infer that the disenchantment with American democracy is not inherently a loss of faith in democracy itself, but a democracy built on false promises and that serves to enfranchise a select while enforcing a multitude of racist, classist policies at the expense of poor people of all races, with particular detriment being inflicted upon people of color.[5] As limited as White’s application of fighting for racial equality presents itself, essentially acting as a form of cold-warrior action, the potential danger of allying African-American organizations with the radical left was not without truth. By framing a pro-American, patriotic application of anti-racism, the possibility of winning the fortune of the United States in their efforts held some modicum of plausibility. Walter White maintained a legitimate anti-communism, however one P.L. Prattis reasoned to distance the movement for racial equality from Communism would prevent the further suppression of the movement at the hands of the United States. To quote; “In the light of the present attitude in the United States toward communism” it was dangerous for Blacks to cooperate with communists, “even though it might be right in principle.”[6] As India maintained a position of non-alignment, maintaining a distance from Communism and influence from the Soviet Union and other socialist states strengthened the potential of diasporic coalition between African-Americans and Indians. Citations [1]Slate, Nico. “Introduction.” In Colored Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom In the United States and India, 2. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012. [2]Slate. Chapter 1, Race, Class, and Nation. In Colored Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom In the United States and India. 7. [3]Slate. Chapter 6, Building a Third World. 169. [4]Slate, Chapter 6. 172. [5]For information regarding the distinctions between capitalist democracy and workers/proletarian democracy, see Stalin, J.V. “The Dictatorship of the Proletariat.” from The Foundations of Leninism, Chapter 4. Marxists Internet Archive, n.d. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1924/foundations-leninism/ch04.htm. [6]Slate. 176. AuthorJymee C is an aspiring Marxist historian and teacher with a BA in history from Utica College, hoping to begin working towards his Master's degree in the near future. He's been studying Marxism-Leninism for the past five years and uses his knowledge and understanding of theory to strengthen and expand his historical analyses. His primary interests regarding Marxism-Leninism and history include the Soviet Union, China, the DPRK, and the various struggles throughout US history among other subjects. He is currently conducting research for a book on the Korean War and US-DPRK relations. In addition, he is a 3rd Degree black belt in karate and runs the YouTube channel "Jymee" where he releases videos regarding history, theory, self-defense, and the occasional jump into comedy https://www.youtube.com/c/Jymee Archives May 2022

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed