|

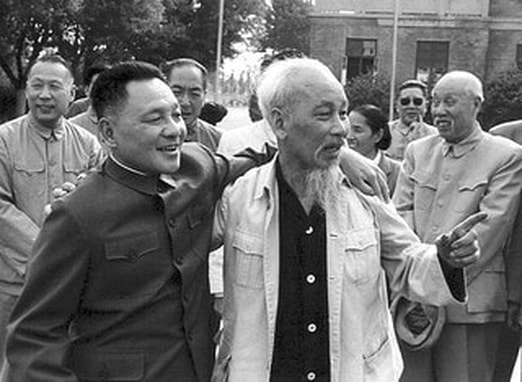

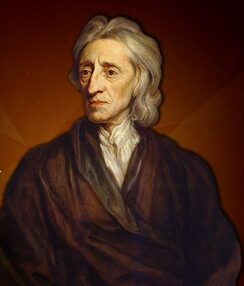

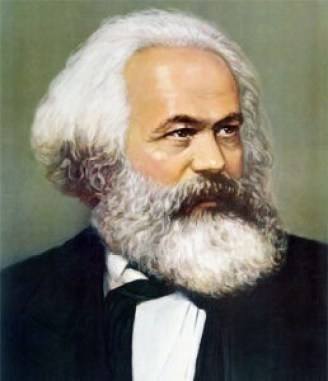

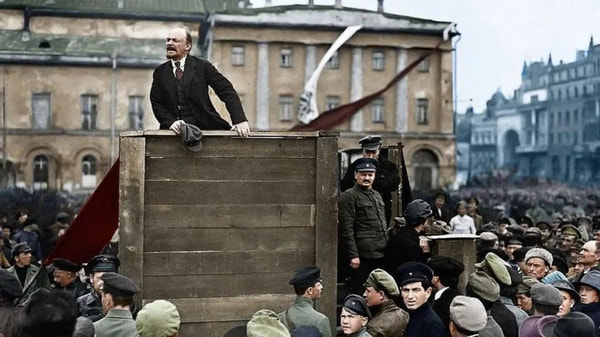

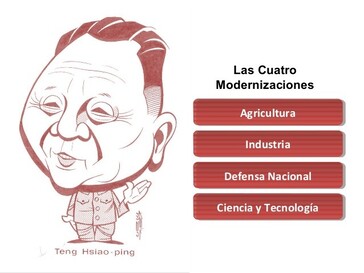

12/20/2021 Deng Xiaoping and Marxism as a proletarian statecraft. By: Sebastián León-Translated By: Valeria BacaRead Now“It doesn’t matter whether the cat is black or white; as long as it catches mice, it’s a good cat.” When we think of modernity we tend to think of capitalism and the legal-political institutions that often accompany it. This can lead us to conceptualize modernity as a mostly negative event, due to the series of bloody historical events that have accompanied and to this day accompany the expansion of capitalism and liberal democracy[1]. For this reason, we tend to forget its “subjective,” “cultural” or, more precisely, “normative” face: the fact that, initially, for the main intellectual and political representatives of the incipient bourgeois culture, modernity was thought of fundamentally as a political project of Platonic roots, whose purpose was the rational organization of society in favor of individual well-being and general prosperity. Nowadays, we tend to think of liberalism as a political ideology that defends "individual freedom" (thought of, in purely abstract and negative terms, as the lack of constraints), but the father of liberal political theory, John Locke, understood his philosophical-political proposal as the defense of a new "statecraft[2]", according to which the best way for a State to become rich, prosperous and powerful was, on the one hand, the increase of arable land in its territory, and on the other, guaranteeing the right of individuals to use them to increase their value (and, of course, the availability of labor ready to work)[3]. The freedom defended by this first version of liberalism did not imply so much the freedom of individuals in the full meaning of the term as the possibility for them to freely dispose of their property[4] and to participate in a series of economic transactions based on the principle of free trade[5]. Locke was not so much a democrat as the defender of an elite government whose legitimacy rested on the possession of knowledge about the correct way to govern (that is: to organize society); what differentiated this enlightened liberal elite from the old Platonic aristocracy is that their wisdom linked the prosperity of the State inextricably to the right of the individual to seek their own well-being (even in the restricted dimension of the economic)[6]. Eventually, with the overcoming of the feudal mode of production and the development of the market economy, this novel art of liberal government would evolve into the first properly modern science: political economy. The Scottish Adam Smith, father of this new science, would perfectly understand the relationship between markets and government, insisting in his famous work The Wealth of Nations (which he defined as a treatise on government) that the latter was not only the one in charge of creating the moral, legal and institutional conditions[7] that made the existence of markets possible, but that it had to use them to create a balance between the antagonistic forces of the different social classes that made up the political community. For Smith, a good ruler had to rise above the short-term interests of businessmen and workers, establishing conditions that would lead them to increase the productivity of social work and generate a degree of wealth that would conduct the nation towards general opulence[8]. The German philosopher Georg Hegel, whom Marx considered his teacher, would go a step further than Smith, explaining what to him was the fundamental principle of the modern nation State: “The essence of the modern state is that the universal be bound up with the complete freedom of its particular members and with private well-being.”[9] Unlike liberal thinkers, Hegel (who besides being influenced by Smith’s economic ideas, was also heavily influenced by French republicanism[10]) considered that modern individuals would not be satisfied with the mere pursuit of the economic interest: the modern idea of individual well-being (tied, as we have mentioned, to the idea of peace and collective prosperity) evolved in such a way that no individual was capable of conceiving their own well-being as something independent of the highest possible degree of individual freedom. Hence, to Hegel, a society that did not guarantee both freedom and material well-being to every single one of its citizens (no longer merely subjects), was a society inevitably condemned to destroy itself from within, corroded by the struggle between those who could enjoy this right and those who could not. Thus, to Hegel, the historical crucible from which bourgeois society emerges, results in the fact that for the first time in history, freedom, along with the material well-being that allows it to be enjoyed, becomes an ethical obligation of society to every single one of its members, which if not satisfied would lead to a crisis of legitimacy of the institutions and to social chaos. In short, the German author recognized that if society did not live up to its obligations towards its members, the latter had no greater reason to respect or preserve it. The paradox of bourgeois society, of which Hegel was already aware, is that the same market mechanism that would have allowed it to produce more wealth than at any other time in human history - that is, the imperative of capital accumulation - at the same time would have given rise to the most inhuman misery that has ever existed, increasing the lines of the dispossessed at the same rate as the wealth produced being concentrated in fewer and fewer hands[11]. This reality meant that a growing sector of society could not benefit from the material and cultural wealth being produced, and that, as a consequence of this precariousness, it was impossible for them to live freely (becoming a permanent risk for bourgeois society). However, although Hegel came to glimpse the problem and proposed a series of corrections to keep society cohesive, Marx will be the first to understand that it is a structural failure of the capitalist system, a necessary law of its operation that cannot be overcome from the coordinates of the same: <<The same causes which develop the expansive power of capital also develop the labor power at its disposal. The relative mass of the industrial reserve army thus increases with the potential energy of wealth. But the greater this reserve army in proportion to the active labor army, the greater is the mass of a consolidated surplus population, whose misery is in inverse ratio to the amount of torture it has to undergo in the form of labor. The more extensive, finally, the pauperized sections of the working class and the industrial reserve army, the greater is official pauperism. This is the absolute general law of capitalist accumulation.>> [12] For this reason, Marx would no longer propose palliatives, but rather directly attack the structural root of the problem: the bourgeois institution of private property, the ultimate foundation of capitalist control of the means of production and of all capitalist social relations, as well as the efficient cause of the insurmountable asymmetry of social power between workers and capitalists. Only by abolishing private property of the means of production and transcending capitalism will it be possible to achieve in the material world that harmony between the universal interest of society and the freedom and well-being of each particular individual which Hegel considered the "essence" of the modern State. Paradoxically, making this ideal a reality will imply abandoning any abstract conception of the State as a "neutral" entity, situated above the antagonism between social classes (that is, any ahistorical conception of it). Thus, as it consolidates as the ideology of the labor movement, Marxism will defend a revolutionary political praxis that demands, as a crucial first step for the restructuring of social relations and the radical transformation of society, the seizure of state power by the proletariat and the consolidation of a dictatorship of the proletariat, which inaugurates the road to socialism[13] with the political expropriation of the bourgeoisie. Socialists must leave behind, as a matter of principle, all flirtation with the ideal of an understanding between producing classes and owning classes[14]. For many years, Marxism (dialectical materialism and its application to the social world as historical materialism), would be a theory of revolutionary tactics and strategy, systematization of the experience of struggle of the working class with hopes of a political revolution and the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat[15]. But when the first successful socialist revolutions came, Marxism had to rise to the new circumstances: the revolutionaries who had come to power had to become statesmen. Revolutionary theory had to become a different statecraft from that of the bourgeoisie. A proletarian statecraft was necessary, which would help organize society according to the interests of the working class (and the other popular classes). The fundamental difference between both ways of understanding government is probably found in the method of Marxism, which differentiates it from bourgeois political economy: Marxism has a dialectical and materialistic approach, which presupposes that in the material universe that modern sciences reveal to us there is nothing static, that change and movement always rule in it and that what is in the present in a certain way, under certain conditions, can be transformed into its opposite. For this reason, Marxism does not accept universally valid abstract formulas, and, applying dialectical understanding to society, discovers the field of history (in contrast to bourgeois science, which often ignores the historicity of its objects of study and does not come to understand adequately the internal dynamics of society). Thus, the main characteristic of a governmental apparatus guided by Marxist theory will be its ability to adapt and respond adequately to the crises and problems that arise in the long process during which it seeks to create the material conditions that make possible the elimination of private property, the overcoming of capitalist social relations and the definitive abolition of social classes (in hopes of making an effective reality the modern promise of autonomy and material well-being). Among all the great revolutionaries who have emerged from the ranks of Marxism, perhaps the one who best embodied the ideal of the proletarian statesman has been Deng Xiaoping. This is a controversial claim, not only because there have been so many other great politicians in the history of international communism[16], but especially because of Deng's reputation among some socialist circles, especially among the so-called "Maoists," of having "betrayed" his predecessor Mao Zedong and the Chinese Revolution, and for having led the People's Republic of China "back to capitalism." This accusation, of course, refers to the famous policy of "reform and opening-up" initiated by the Chinese leader in the early 1980s, which finds its theoretical justification in what the Chinese Communist Party calls the "Deng Xiaoping Theory.” I would like to briefly defend that it is precisely in the reform and opening-up and in the Deng Xiaoping Theory that we can identify the perfection to which Deng led Marxism, understood as a statecraft. First, it is necessary to ask, where did the accusations against Deng derive? The answer is simple: they derive, mainly, from the identification of socialism with the collectivization of property, based on the model established in the USSR by Stalin at the beginning of the 1930s, and which, with more or less differences, most socialist countries would adopt during the second half of the 20th century. However, this identification forgets, in the first place, the economic history of the USSR: the first socialist country in the world, had at least three different economic models, the first of which was called “War Communism” (basically, the rationing of resources, the distribution of scarcity to survive the period of wars); the second would be Lenin's so-called “New Economic Policy,” whose main objective was to use private investment and entrepreneurship to rebuild and develop Soviet production. Lenin would have stated on at least one occasion that his intention was for the NEP to be applied for a long time[17]; be that as it may, the imminence of war would lead Stalin to initiate the process of collectivization that would make possible the accelerated industrialization of the USSR, under the leadership of the State. Thus, both the processes of change in the organization of the USSR’s economy, as well as the concrete events that in each case would lead the Soviet State to carry out said changes, tend to be forgotten. Second, the economic history of the People's Republic is often forgotten: while the CCP did not come to seize control of the entire mainland China until 1949, several regions had been under its rule for at least twenty years before; in these regions, the Party experimented with different forms of property organization: both “state” property, under the Party's command, and private property and cooperatives. In other words, it was a “mixed” organization of production[18]; in 1940, on New Democracy, Mao defended this "peculiar" character of the Chinese Revolution, its refusal to completely expropriate private owners, due to the backwardness of the Chinese economy[19]. For the father of the People's Republic of China, the revolution in countries like his had to go through two stages, or through a revolution in two parts: a moment of political revolution (of the creation of a "democratic" and sovereign institutionality, in the sense that it should be directed by the popular classes, that is, by the alliance between workers and peasants, led by the Chinese Communist Party, differentiating itself from the formal democracy of the West and adapting to the particular needs of the Chinese people, putting the development of productive forces at the service of national interests) and one of social revolution (during which the fruits of production could be used to progressively transform social relations into post-capitalist relations, definitively abolishing private property and the State as a form of class domination, leading to a complete socialization of the means of production)[20]. In the first stage, the private property of the bourgeoisie would not be completely expropriated, but it would be subjected to a political expropriation[21]. It would not be until 1958, largely as a consequence of the Sino-Soviet split and the withdrawal of economic aid from the USSR (in addition to the permanent threat of US imperialism), that the collectivization of the Chinese economy would be opted for. As is known, this attempt at economic collectivization (between 1958 and 1976) did not have good results, and it would be abandoned shortly after Mao's death[22]. Coming to power in 1978, Deng Xiaoping would initiate a radical process of change in the People's Republic. The situation in the country at that point, economically and socially, was quite critical, as a consequence of the serious mistakes made in the previous two decades. On the basis of what could be rescued from the previous period (advances in education, health and life expectancy), Deng initiated a series of reforms that would begin in the countryside (gradually transforming the communal property regime into one of family property that would allow peasants to manage their land and grow and sell their products on the market[23]), which would lead to the progressive opening of China to the international market. Already at this moment it was evident, for more than a decade, that the productivity of the USSR and the other socialist countries had begun to stagnate, and that they were entering a serious recession; it was becoming clear that the heroic incentive of the workers (their patriotic and revolutionary impetus, their need to carry on production in the name of the nation and the revolution), which had served Lenin's homeland so well during the first decades of its existence had begun to run out during the period of “peaceful coexistence.” Therefore, the market, with its material incentive, would have to be used as a tool to increase the productivity of the Asian giant. Deng would justify this recourse to the market: The proportion of planning to market forces is not the essential difference between socialism and capitalism. A planned economy is not equivalent to socialism, because there is planning under capitalism too; a market economy is not capitalism, because there are markets under socialism too. Planning and market forces are both means of controlling economic activity. [24] The complete nationalization of banks and tough antitrust legislation would allow the CCP to condition capital investments in China, and opening up to foreign capital would allow for the first time a socialist country to overcome the harsh technological blockade imposed by the US. Likewise, the State would retain control of a series of key industries (including heavy industry), putting the production of consumer goods in the hands of the market (in which adequate production and distribution the main limitations of the planning were presented). In this way, the market could be used to increase productivity (that is, to generate value) rather than to generate profits (mere exchange value) without benefiting the rest of society. This shed light on that infamous mantra of the Reform and Opening-up period, traditionally attributed to Deng: "To get rich is glorious." In an interview, when asked what this phrase could have to do with communism or socialism, Deng would answer: According to Marxism, communist society is based on material abundance. Only when there is material abundance can the principle of a communist society - that is, 'from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs' be applied. Socialism is the first stage of communism. Of course, it covers a very long historical period. The main task in the socialist stage is to develop the productive forces, keep increasing the material wealth[25] of society, steadily improve the life of the people and create material conditions for the advent of a communist society. There can be no communism with pauperism, or socialism with pauperism. So to get rich is no sin. However, what we mean by getting rich is different from what you mean. Wealth in a socialist society belongs to the people. To get rich in a socialist society means prosperity for the entire people. The principles of socialism are: first, development of production and second, common prosperity. We permit some people and some regions to become prosperous first, for the purpose of achieving common prosperity faster. That is why our policy will not lead to polarization, to a situation where the rich get richer while the poor get poorer.[26] Thus, under the leadership of the CCP, on the one hand, the investment had to be used to create infrastructure, security and jobs where they were needed[27]; likewise, the guarantee of competition[28] should encourage technological innovation and increased productivity. Finally, with the arrival of foreign capital, the Chinese people would learn little by little to produce the technology that had become key to consolidate themselves as an economic power (freeing themselves in the process of economic dependence on the capitalist powers and reconfiguring the international correlation of forces). However, for Deng none of this would be possible if the institutionality created by the CCP during the previous years were not maintained: the future of China was married to the implementation of democratic centralism and the iron leadership of the Communists. Only by maintaining its own form of government, different from the liberal parliamentarianism of the West, could the so-called “Four Modernizations” (agriculture (1), industry (2), defense (3) and science and technology (4))[29] become a reality. As can be seen, this idea of Deng fits perfectly in the line established by Mao four decades earlier on New Democracy. So far we have seen the first pillar of the Deng Xiaoping Theory: the need for the Communist Party government to make use of the market to create wealth for all of society, disciplining entrepreneurs through competition and the use of subsidies to develop the productive forces[30]. We see here that the reform and economic opening-up become a principle of government, a tool to govern in the modern way; it is this first pillar of his theory that Deng Xiaoping called "socialism with Chinese characteristics." The second pillar of the Deng Xiaoping Theory would have to do with his reinterpretation of Mao Zedong's thought: Deng would highlight the importance of recognizing the debt of Chinese society with Mao, and the importance of his teachings as a revolutionary and theorist of Marxism-Leninism, but he was not to be elevated to the status of a deity. Mao had been capable of making mistakes (some quite gross); the fundamental of his thought was in his defense of the scientificity of Marxism, in his call to “seek truth from facts” (the crucial recognition of practice as the only criterion of truth). To make Mao Zedong's thinking dogmatic was to move away from Mao's teachings, it was to refine his scientific thinking. This would not only allow Deng to legitimize himself before the cadres and before Chinese society, establishing the continuity between him and Mao, but also to epistemologically base his theory: the need for the Reform and Opening-up in socialism with Chinese characteristics was based on experience, in the confrontation of reality with practice and the consequent learning. In this sense, the Deng Xiaoping Theory can be conceived as an innovation within Mao Zedong's Thought. To conclude this long essay, we can see to what extent Deng picks up on Mao's idea that socialism is a long process of transition between capitalism and communism as a post-capitalist classless society, and not a clearly defined mode of production. What allows us to get from one point to another would be the leadership of the Communist Party, which must create the material conditions to break with capitalist social relations and their harmful consequences. For this, the Party can employ various resources, such as planning or the market economy, as required by objective conditions; the fundamental thing about this proletarian statecraft would be that, unlike the bourgeois statecraft, it recognizes (1) that the interests of the capitalist class, directly linked to profit, prevent a healthy development of society [31], (2) so they must be removed from political power and state institutions; (3) also, that this can only be achieved by putting the proletariat, the peasantry, and the popular classes in general in political power. Finally, (4) the State and its institutions must have the capacity to adapt quickly to circumstances, to recognize and correct errors, and to restructure their policies accordingly[32]. Only in this way can the degree of material wealth that can make the normative principle of modern government come true, according to which the basis of government is to guarantee the well-being of each member of society and to maximize their freedom. Only the recognition of the importance of class struggles and of the need for the dictatorship of the proletariat can ultimately lead us to the "general opulence" of which Adam Smith spoke, and which is nothing other than the overcoming of capitalism and the realization of communism. Deng Xiaoping stands on the shoulders of giants, certainly, but he was the first to understand this with all clarity, as the results of his governmental practice demonstrate. Notes: [1] And that those of us that live in the postcolonial periphery know so well. [2] The Anglo-Saxon term would be "statescraft." Here the word "craft" does not refer so much to an aesthetic production (that is, artistic) as to the root of the term "craftsman," which refers to the ability to do or produce something methodically, that is, by applying a series of rules or precepts; it would be a matter of "practical knowledge" rather than theoretical knowledge. Another word that is close to its meaning in Spanish could be "technique". In the West, the tradition of statecraft and the problem of the education of rulers has its roots in the philosophy of Ancient Greece (specifically, in the philosophy of Plato); however, it would have come to Greece from Asia, finding precedents in the traditions of Persia, India, China, etc. [3] See Locke, J., Second Treatise of Government. [4] Including among the properties, particularly in the case of the poor, the body itself understood as labor power. [5] The root of the term "liberal" would not be "freedom", but rather "liberality", a synonym for "generosity" that the modern Anglo-Saxon intelligentsia (from Thomas Hobbes to David Hume) considered as the virtue par excellence of the aristocracy: the modern ideal of the ruling class was that of a liberal, generous class, since in the long run its policies should bring a degree of bonanza that could eventually be enjoyed by even the poorest of the State's subjects. Here we find the historical precedent for the famous "trickle-down effect" of neoclassical economic theory. [6] Of course, other important aspects of Locke's political theory are omitted here, such as his inhuman defense of the institution of slavery. For Locke, the space of economic freedom guaranteed by the liberal government was perfectly compatible with the deprivation of all rights to those individuals who, for one reason or another, did not hold the status of subject of the State nor, as a consequence, the privilege of participating in that space (these plagued people included both those who were considered a threat to property rights and those who were considered racially inferior because of their 'primitive' culture - at certain periods in English history the dividing line between these two subsets became more or less diffuse; see D. Losurdo, Liberalism: A Counter-History). [7] And, of course, also military. [8] See Smith, A., An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. [9] See Hegel, G. W. F., Elements of the Philosophy of Right. [10] It would be in the context of the French Revolution and the multiple revolutions that followed that, little by little, a people’s statecraft would begin to emerge (as opposed to the bourgeois statecraft). We will return to this idea later. [11] In Das Kapital Marx finishes developing this idea, explaining how the imperative to lower production costs to maximize profits leads, on the one hand, to replace human labor with technology (increasing the numbers of the "industrial reserve army", which have lost the "privilege” of being exploited and become a threat to the working conditions of those who are still employed), and on the other, to an aggressive competition between capitalists, in which the smallest capitals are eventually taken out of the competition and engulfed by the largest capitals. [12] See, Marx, K., Das Kapital. [13] The transitional period between capitalism and a post-capitalist, classless society (which we agree to call, with Marx and Engels, communism). [14] Lenin, V., State and Revolution. Lenin will denounce the opium dream of harmony between social classes that periodically resurfaces within the socialist movement as a symptom of the corruption of a more privileged sector of the European working class by the capitalists (benefiting from better working conditions, guaranteed by extracting surplus value from the colonial periphery). Thus, for example, the turn of the Social Democracy towards reformism during the time of the Second International was largely explained by the “gentrification” of the workers' leaders in Western Europe. [15] Lenin would say that Marxism should be understood as "the concrete analysis of the concrete situation" (in contrast to social democratic revisionism, which supported a metaphysics of history, in which all backward societies had to necessarily develop as a reflection of European history, going through one by one a fixed series of "historical stages" before reaching bourgeois society and eventually socialism). In the conditions of imperialism, Lenin would bet on the support of the working classes for the national liberation struggles of the colonial and semi-colonial countries; in the national conditions of Russia, by a popular alliance with the peasantry. In the particular conditions of Peru, Mariátegui would bet on a socialism in which the indigenous people occupy a leading place, and in those of China, Mao Zedong would propose the strategic line of a revolution that would go "from the countryside to the city," with the peasantry as the main political actor. [16] It is important to mention that, during his years as the head of the People’s Republic of China, Deng and his fellow compatriots could enjoy a very high level of social peace and stability compared to what other socialist leaders and their respective countries came to know. The strategic alliance and trade agreements that Mao Zedong forged with the US after the unfortunate Sino-Soviet split freed the People's Republic of much of the pressure that US imperialism has historically exerted on socialist countries. Also important was the abandonment of the political line that had been inaugurated during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. [17] “In earnest and for a long time” the founder of the USSR would say during the closing of the Tenth Russian Conference of the Russian Communist Party in 1921. The fact that Deng Xiaoping lived in the USSR during the implementation period of the NEP is not a secondary fact. During the 1980s, several years after China's economic opening began, Deng would say that perhaps the NEP model in the USSR was the most correct model to achieve socialism. [18] See Losurdo, D. [19] Some of Mao followers forget this fact; others consider that Mao was at the time in the wrong position. Marxists who despise the Chinese Revolution and the People's Republic, for their part, consider these positions to be evidence that China was "revisionist" since the time of Mao. I consider that, in effect, there is a certain continuity between Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping here, although I do not think that either of the two revolutionaries was a "revisionist" (unless revisionism implies heterodoxy; however, Stalin and Lenin themselves would have been heterodox at their time, and would have opposed Bolshevism to the “dogmatic Marxism” of Social Democracy). [20] See, Mao, Z., On New Democracy. [21] The idea is in Mao, but the precedent is in Lenin's NEP (a capitalist class that the ruling proletarian class allows to enrich itself in the name of national interests). Capitalist exploitation partially persists, but for the first time in history it is the exploited class that possesses political power. [22] Chinese collectivization would have important differences with the one carried out in the USSR. Mao's intention would be to rely less on cadres for planning and more on direct deliberation by the masses. Hua Guofeng, Mao's immediate successor before Deng's consolidation, would seek to adopt a policy more similar to that followed by the USSR during the previous decade. His lack of ability as a ruler would lead him to depend more and more on Deng, who would eventually assume power, never officially holding the positions of head of government or of the CCP. [23] Giovanni Arrighi, in his book Adam Smith in Beijing, insists on the importance of these reforms in the countryside: in Arrighi's opinion, it would be the livelihood that the bulk of Chinese workers (of peasant origin) can obtain independently from work in the cities, and the establishment of cooperatives in their places of origin, one of the great differentials of the PRC with respect to capitalist countries. [24] Deng, X., Excerpts from Talks given in Wuhan, Shenzhen and Shanghai. [25] Italics are mine. [26] Interview to Mike Wallace. [27] It is important to mention here the Special Economic Zones, where capitalist social relations are tolerated. [28] Which Adam Smith already recognized was always at risk because it was contrary to the interests of businessmen, and had to be guaranteed by government intervention. See Wealth of Nations, Book I. [29] The Four Modernizations, pillar of socialism with Chinese characteristics, would be enumerated for the first time in 1963 by the then Premier of the PRC, Zhou Enlai. [30] One could think of the use of capitalists as “fuel” for Chinese modernization. [31] For reasons of space this idea has not been developed sufficiently, but it also gives rise to the dependent relationship of the Third World with respect to the First, neocolonialism, and the international class struggle that us Marxists call imperialism. [32] Which implies, needless to say, an immense capacity to gather and manage resources according to the need of each context. Author Sebastián León is a philosophy teacher at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, where he received his MA in philosophy (2018). His main subject of interest is the history of modernity, understood as a series of cultural, economic, institutional and subjective processes, in which the impetus for emancipation and rational social organization are imbricated with new and sophisticated forms of power and social control. He is a socialist militant, and has collaborated with lectures and workshops for different grassroots organizations. Translated By Valeria Baca is an undergraduate student pursuing a degree in veterinary medicine at the Autonomous University of Ciudad Juarez. She hopes to help bridge the gap between Spanish and English marxist content by translating articles. This article was originally published in spanish by Instituto Marx Engel of Peru. Archives December 2021

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed