|

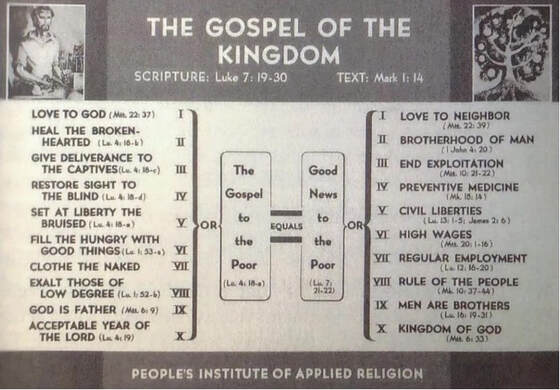

People's Institute of Applied Religion, founded by Claude C. Williams of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union “We therefore see that the Christianity of that time [referring to the book of Revelation] which was still unaware of itself, was as different as heaven from earth from the later dogmatically fixed universal religion of the Nicene Council; one cannot be recognized in the other. Here we have neither the dogma nor the morals of later Christianity but instead a feeling that one is struggling against the whole world and that the struggle will be a victorious one; an eagerness for the struggle and a certainty of victory which are totally lacking in Christians of today and which are to be found in our time only at the other pole of society, among the Socialists.’’ The views of the foundational figures of Marxism on the question of religion are not well known, except to depict Marxists as hostile toward religion. A few lines before his infamous depiction of religion as “the opium of the people,” Karl Marx, in an introduction to his Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, writes, “The struggle against religion is, therefore, indirectly the struggle against that world whose spiritual aroma is religion.” While Marxism undeniably arose from a critique of the atheistic “materialism” of Feuerbach, this distinction Marx makes about “the struggle against religion” is worth noting, and also seems discernable in later Marxist analyses of religion like Lenin’s 1905 essay “Socialism and Religion.” In Lenin’s time, as Karl Polanyi noted, the Czarist (Caesarist) feudal power structure faced little opposition from the ranks of the Orthodox Church. (“The Essence of Fascism”) After the famous “opium of the people” sentence, Marx continues with lines that are less quoted: “The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.” Similarly, the views of the foundational figures of Christianity on the question of class struggle are not well known, except those scriptures which can be used to pacify the masses. Rarely is the scripture from the Epistle of James quoted from American pulpits, “Is it not the rich who oppress you?” (James 2:6) In Ludwig Feuerbach and the Outcome of Classical German Philosophy, Engels wrote of early Christianity, “What it originally looked like has to be first laboriously discovered again, since its official form, as it has been handed down to us, is merely that in which it became a state religion, to which purpose it was adapted at the council of Nicaea.” In the Epistle of James, the unknown church father warns against showing partiality to those who “wear gold rings,” which in the Roman imperial context certainly included emperors like Constantine. By giving the Roman emperor a seat at the council of Nicaea, the church fathers of the fourth century may have not only been ignoring the warning of James, but may also have been betraying the very counter-imperial theology which proclaimed Jesus of Nazareth the “Son of God,” an epithet of the Roman emperor. If the Roman emperor was the antichrist of John’s Revelation, surely the word of Our Lord would apply, “No one can serve two masters; for a slave will either hate the one and love the other, or be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and wealth.” (Matthew 6) Church fathers who came just after the generation of Nicaea like Ambrose of Milan and Basil the Great may represent some of the class politics that was considered “orthodox” before the full integration of the church into the Roman Empire. In his sermon “On Naboth,” Saint Ambrose claims that greedy Ahabs and murdered Naboths are born every day, referring to the story in I Kings of a monarch who kills a poor man in order to take his property. “How far, O rich, do you extend your mad greed? ‘Shall you alone dwell upon the earth’ (Isa. 5:8). Why do you cast out the companion whom nature has given you and claim for yourself nature’s possession? The earth was established in common for all, rich and poor. Why do you alone, O rich, demand special treatment?” (Ambrose “On Naboth”) Basil the Great says, “The beasts become fertile when they are young, but quickly cease to be so. But capital produces interest from the very beginning, and thus in turn multiplies into infinity. All that grows ceases to do so when it reaches normal size. But the money of the greedy never stops growing.” (Basil, Homily on Psalm 14) The whole of Christian history is worth analysing from the perspectives of class, patriarchy, disability, ecology, and colonialism. One period of Christian history was analysed by Frederick Engels in his 1850 book The Peasant War in Germany. A rival Reformer to Martin Luther, the German preacher Thomas Müntzer wrote in an 1524 anti-Luther pamphlet titled A Highly Provoked Defense, “Whoever wants to have a clear judgement must not love insurrection, but equally, he must not oppose a justified rebellion.” (Sermon to the Princes) He continues, “The people will be free. And God alone will be lord over them.” (p. 92) A year later, Müntzer was tortured and executed as a leader of the German Peasant Rebellion. While Luther worked to integrate his Reformation into the feudal power structure of 16th century Germany, Müntzer railed against the land-owning nobility who dominated Early Modern Europe. Instead of assimilating to the values of the kingdoms of earth, Müntzer pointed to the example of the early church in Acts 2 and 4: omnia sunt communia — “all things held in common.” “The stinking puddle from which usury, thievery, and robbery arises is our lords and princes. They make all creatures their property—the fish in the water, the bird in the air, the plant in the earth must all be theirs. Then they proclaim God's commandments among the poor and say, ‘You shall not steal.’” (A Highly Provoked Defense) Engels describes Müntzer’s gospel in glowing terms: “By the kingdom of God, Muenzer understood nothing else than a state of society without class differences, without private property, and without superimposed state powers opposed to the members of society.” For many, Müntzer falls into the category of history reserved for so-called “idealists” (not the Hegelian kind per se)—seemingly crazed martyrs like the 19th century abolitionist John Brown. A similar lone radical figure is present in both the synoptic gospel narratives of Jesus’ life and the Antiquities of Josephus. “A voice crying out in the wilderness Josephus identifies him as “John, who was called the Baptist.” His account of John’s death reads: “Now many people came in crowds to him, for they were greatly moved by his words. Herod, who feared that the great influence John had over the masses might put them into his power and enable him to raise a rebellion (for they seemed ready to do anything he should advise), thought it best to put him to death. In this way, he might prevent any mischief John might cause, and not bring himself into difficulties by sparing a man who might make him repent of it when it would be too late.” (Jewish Antiquities 18.118) This account of the reasoning for Herod’s execution of John the Baptist is different from that which is reported in the gospel narratives, but has strong resonances with other passages in Matthew and Luke. A very obscure saying like “From the days of John the Baptist until now the kingdom of heaven has suffered violence, and the violent take it by force,” seems to reflect the kind of violent revolutionary conflict that indeed took place in Roman-occupied Palestine. Many rebellions were even led by men who claimed to be the Messiah. There is obvious evidence to support the notion that a potentially historical Jesus of Nazareth chose the path of nonviolent resistance to Roman oppression rather than the path of the Zealots. However, Jesus’ alleged proximity to the figure of John the Baptist may be an indication of the revolutionary nature of the original Jesus movements, or at least the attitudes of the ruling classes towards the movement while it was on the rise. (Horsley’s Jesus and Empire is an accessible primer on first-century Palestinian resistance to Roman rule.) John the Baptist, who calls the elite factions of Palestine a “brood of vipers,” apparently requested confirmation that Jesus was the “one who is to come” while he was incarcerated in Herod’s prison. As economist Michael Douglas and theologian Sharon Ringe have pointed out, Luke and Matthew record Jesus answering John’s messengers: “The poor have good news brought to them.” While Jesus and John’s movements may have been separate, this message apparently united them. The gospels of Luke and Matthew also corroborate Josephus’s observation that the rulers of Palestine “feared the people.” In Luke, when Jesus asks the religious establishment if John’s baptism was of divine or human authority, they consult amongst themselves, “If we say, ‘From heaven,’ he will say, ‘Why did you not believe him?’ But if we say, ‘Of human origin,’ all the people will stone us; for they are convinced that John was a prophet.” Later in the same chapter, Luke says the chief priests and scribes “wanted to lay hands on him at that very hour, but they feared the people.” (Luke 20:19) Perhaps that is why in Luke 22, the religious leaders enlist the “temple police” to help them apprehend Christ. (22:52) “For I tell you, this scripture must be fulfilled in me, ‘And he was counted among the lawless.’” (22:37) Indeed, the cross was typically used to execute slaves like Spartacus, rebels, and bandits. In 1940, radical folk singer Woody Guthrie wrote a song titled “Jesus Christ,” which identifies “the bankers and the preachers,” “the landlord, cops, and soldiers” as the ones who “laid Jesus Christ in his grave.” Guthrie died a poor man in 1967, the same year as his contemporary Langston Hughes, whose poem “Bible Belt” anticipates the theology of the great James Cone: It would be too bad if Jesus The Nazarene once proclaimed the gospel in a field: “Blessed are the poor, for yours is the kingdom of God.” Let that kingdom come, through our wills and our actions. Through God’s will and spirit. On earth as in heaven. Just four verses after Christ’s final sermon in the book of Matthew (‘Truly I tell you, just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me.’), a woman comes to anoint Jesus at the house of a leper. (Matthew 26) When his disciples try to condemn the woman’s use of fine perfume as wasteful, Jesus responds in what I imagine to be the sarcastic tone he used toward the Pharisees and Herodians who tried to catch him with a question about paying taxes to Caesar. As Reverend Dr. Liz Theoharis shows in her book Always With Us?, the phrase, “You will always have the poor with you,” is a reference to the law of Jubilee in Deuteronomy, a book Matthew’s gospel draws heavily from. “Every seventh year you shall grant a remission of debts. [...] There will be no one in need among you, if only you will obey the Lord your God by observing this entire commandment.” (Deuteronomy 15) Let the law be fulfilled in our hearing and doing. Luke’s gospel, cited repeatedly above, seems to present a more noticeably class-conscious version of the already egalitarian good news presented in Matthew and Mark. As Dennis MacDonald has noted, the Gospel of John, known as the latest gospel, seems to take issue with some of Luke’s narrative—notably in his transformation of Lazarus the parabolic homeless man into a friend of Jesus who is raised from the dead. Both Lazarus stories deal with resurrection: in Luke, a rich man who ignored the begging Lazarus at his gate, calls out to Abraham from the fires of Hades, asking him to send Lazarus back to the land of the living to warn his family of the coming judgement on the rich. “Remember that during your lifetime you received your good things, and Lazarus in like manner evil things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in agony,” Abraham says. “If they do not listen to Moses and the prophets, neither will they be convinced even if someone rises from the dead.” (Luke 16) Revolutionary and first president of Burkina Faso Thomas Sankara said, “No altar, no belief, no holy book, neither the Qur’an nor the Bible nor the others, have ever been able to reconcile the rich and the poor, the exploiter and the exploited. And if Jesus himself had to take the whip to chase them from his temple, it is indeed because that is the only language they hear.” The exploitation of the poor by the rich is indeed condemned by our holy books, from the prophets Micah, Amos, Jeremiah, Isaiah, and Habakkuk, through the gospels and epistles. After rejecting the rich young ruler, Christ says with God all things are possible. But a camel does not pass through the eye of a needle without a miracle. (Mark 10) If the light within you is darkness, how great is that darkness! Such blindness befalls a world which bows before the altar of Mammon. The imperialist “wisdom of the rulers of this age” is foolishness to God. The economy was made for humanity, not humanity for the economy. Historian Christopher Wilson wrote recently about Juneteenth for the Zinn Education Project, “As with an incarcerated prisoner who may be told she is free, until the prison bars are unlocked that word only results in theoretical freedom.” Freedom, abolition, and justice are words which must become flesh. The epistle of James speaks again, “Be doers of the word, and not merely hearers of the word who deceive themselves.” Mary proclaims the good news of our Deliverer: He lifts up the lowly and fills the hungry with good things. For those who cause the least of these to stumble, Christ prophesies the millstone. “God wept; but that mattered little to an unbelieving age; what mattered most was that the world wept and still is weeping and blind with tears and blood. For there began to rise in America in 1876 a new capitalism and a new enslavement of labor. Home labor in cultured lands, appeased and misled by a ballot whose power the dictatorship of vast capital strictly curtailed, was bribed by high wage and political office to unite in an exploitation of white, yellow, brown and black labor, in lesser lands and “breeds without the law.” Especially workers of the New World, folks who were American and for whom America was, became ashamed of their destiny. Sons of ditch-diggers aspired to be spawn of bastard kings and thieving aristocrats rather than of rough-handed children of dirt and toil. The immense profit from this new exploitation and world-wide commerce enabled a guild of millionaires to engage the greatest engineers, the wisest men of science, as well as pay high wage to the more intelligent labor and at the same time to have left enough surplus to make more thorough the dictatorship of capital over the state and over the popular vote, not only in Europe and America but in Asia and Africa. “Decolonization never goes unnoticed, for it focuses on and fundamentally alters being, and transforms the spectator crushed to a nonessential state into a privileged actor, captured in a virtually grandiose fashion by the spotlight of History. It infuses a new rhythm, specific to a new generation of men, with a new language and a new humanity. Decolonization is truly the creation of new men. But such a creation cannot be attributed to a supernatural power: The ‘thing’ colonized becomes a man through the very process of liberation. Decolonization, therefore, implies the urgent need to thoroughly challenge the colonial situation. Its definition can, if we want to describe it accurately, be summed up in the well-known words: AuthorZachary White Kairos fellow, Union Theological Seminar Archives September 2021

3 Comments

9/24/2021 02:35:54 pm

I also think Mark was first gospel, but it probably came after supposed writings of Paul. Mark is beautiful in its simplicity, opens with no nativity, just Prepare the Way of the Lord (Isa 40) and also less of a resurrection appearance at end. Mark has less sermons than Matt and Luke but importantly includes the rejection of Rich Young Ruler, “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God” saying, cleansing of moneychangers from temple, and obviously Roman execution.

Reply

RR

9/26/2021 02:03:46 am

The state uses religion or tries to replace it. Napoleon explained :

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed