|

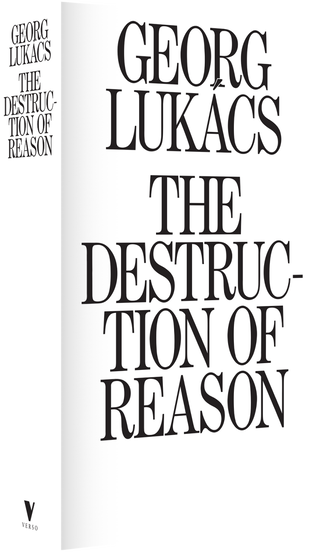

5/19/2024 ON THE GENERAL DISCUSSION DOCUMENT FOR THE CPUSA’S 2024 NATIONAL CONVENTION. PART FOUR: Lessons for Today. By: Thomas RigginsRead NowGDD 3 Part Three— Lessons for today [part one here, part 2 here, part 3 here] This section consists of four paragraphs: 1. The way to fight the fascist danger and secure Biden’s election as President is to mobilize masses of people to support these goals. There follows a brief history of progressive struggles waged in the past for peace and civil rights in which mass actions were responsible for pressuring the ruling class to make concessions which they did to prevent mass consciousness moving in the direction of system change. 2. A list of the concessions granted by the ruling class as a result of mass mobilization. An incorrect explanation is offered to explain why the right-wing was able to take over the government in the wake of these concessions. ‘’The center and left were divided over Civil Rights and the Vietnam War. Those divisions resulted in over a decade of right-wing rule, first with Richard Nixon and then (after Carter) Ronald Reagan.’’ It was not that the center and the left were divided, it was because the center and the right were united. The historical tendency of the center is to move to the right whenever the left begins to mobilize. Center-left or Left-center unity is a losing strategy thought up by the revisionists who reject revolutionary tactical maneuvering in principle [no more Bastilles]. The Left waters down its demands to accommodate the center and at the crucial moment of the struggle the center defects to the right. All those centrist Democrats in the Solid South who supported the New Deal defected to the ultra-right Republican Party when the Civil Rights Act was passed. 3. ‘’The demand for complete equality called for the completion of unfinished bourgeois-democratic business, not only from the founding of the Republic, but also by the betrayal of Reconstruction and segregation.’’ The founding of the Republic included the recognition of slavery and the right to own slaves was recognized in the constitution until after the Civil War— as far as bourgeois democratic business was concerned there was no problem at the time with ending Reconstruction and imposing segregation. The job of the bourgeois democratic revolution is NOT the demand for complete equality, nonsense from the bourgeois viewpoint, but to enshrine the bourgeoisie as the ruling class and the working class as the subject class— this has been accomplished. The Road to Socialism leads to the overthrow of bourgeois democracy by working class democracy and the greatest roadblock to that is the myth of center-left unity. [Actual praxis is a little more complicated but this is the theoretical essence of Marxism-Leninism.] 4. The CPUSA played an honorable role in the civil rights and peace movements but the major leadership roles came from the forces of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the NAACP, and other civil rights groups, such, CORE, SNCC and the Urban League. There were some overlaps between the civil rights and anti-war and peace movements featured by the rise of the Black Panthers and the most important youth movement SDS. This section ends as follows-- ‘’just as in the ’60s, the country is confronted by a triple threat: this time from Trump and fascism on the right, bipartisan support for war, and a many-sided class war on democracy and labor at home and abroad.’’ But it should be noted that the threat from fascism is not just from Trump and the right, but also from Biden and the ‘mainstream’ Democrats. Recently Biden signed the renewal of the FISA foreign surveillance act which allows the government to, without a warrant, spy on every American that has any electronic device, phone, TV set, radio, etc., and force anyone with such a device to spy on others and report the findings to the government. Senator Ron Wyden [ Dem. Oregon] said the bill was “one of the most dramatic and terrifying expansions of government surveillance authority in history.” This is just the type of fascist control bill the left would have expected from Trump but it is from Biden. This fascist part of the bill was originally added under Bush in 2008 and has been reauthorized by Biden. American fascism is a bipartisan enterprise— spying at home, genocide abroad. This is the real ‘’serious jeopardy.’’ The struggle for democracy This section consists of two paragraphs of mumbo jumbo about democracy and the working class in which class issues and bourgeois liberal issues are jumbled together to comprise something called the Communist ‘plus’, which turns out to be the revisionist interpretation of The Road to Socialism plus confusion twice confounded. Let’s see if we can clear up this mess of mixed up faux Marxism. The first paragraph opens by informing us we have to struggle to obtain victory (duh!) and the struggle ‘’includes the GOP assault on voting rights, abortion, trans, and immigrant rights, as well as support for genocidal wars abroad. The challenge is to link these struggles together, and connect them with the fight for a ceasefire.’’ Well, there are at least two ceasefires we need, Gaza and Ukraine. But we also need to get rid of the Cuba blockade, the Venezuela sanctions, the military buildup against China, etc., etc. All these struggles have their own dynamics and involve different sets of interests. Trying to connect abortion rights with voting rights and trans rights with say a Gaza ceasefire is really comparing apples and oranges. Anyway the Democrats are just as bad as the GOP with genocide and ceasefires. The common link here is the capitalist system— it is the class struggle led by the working class that must be the focus for a CP. All these struggles cross class lines, our job is not to ‘’connect them with the fight for a cease fire(sic)’’ but all of them, including the ceasefires, have to be connected to the class struggle. Class reductionist? Absolutely, that is what Marxists do. The paragraph discusses the party’s program and does point out it is working class power that is the key to getting concessions from the ruling class but the whole capitalism versus socialism issue is ignored. Marxists understand the importance of the unions and working class power but without raising the workers class consciousness to socialist consciousness working class power remains mired in the capitalist system and cannot transcend bourgeois democracy— and it’s the limits of bourgeois democracy that is the problem — it’s already given us Genocide Joe and is getting ready to serve up Trump. It is fantasy to think the people can free themselves from oppression by using the system of the ruling class. Let’s look at paragraph two where the issue of Socialism does make its appearance. ‘’Even if at the end of the day, efforts prove unsuccessful, all is not lost. It’s in these battles that deeper lessons are learned about the nature of capitalism. In fact, that’s where working-class experience intersects with revolutionary ideology; that’s where theory is developed. It’s where the Communist Party provides its “plus.” The party helps draw out and theorize experience by highlighting the capitalist causes of the crisis and the need for socialist solutions. Thus, the process of struggle is what leads workers to become conscious of themselves as a class force.’’ There is nothing generally objectionable with this passage. The problem is it does not reflect the actual praxis of the leadership. That praxis, in the press and the website, rarely puts forth a Marxist-Leninist analysis of current events and leans to a praxis oriented towards reformist support for the Democratic Party, at times even viewing the DP as part of its make believe all people’s front or center-left coalition. The Communist ‘plus’ is actually a ‘minus’ in practice. The emphasis on ‘democracy’ is minus as it constantly stresses the term ‘democracy’ indiscriminately and even links it with ‘’Bill of Rights” socialism giving the false impression that workers will not restrict the rights of the class enemy to organize and try to regain power if proletarian democracy comes to power. Class hegemony and a ‘’Bill of Rights’’ in any sense recognizable to Americans, is a contradictio in terminis. The bourgeois ruling class violates its own Bill of Rights at will as student protesters and union organizers find out on a daily basis. What’s New This is an optimistic GDD paragraph putting a spin on the last few years making it appear the progressive movement is riding high. The fact is the Democrats lost the Congress when the Republicans took over the House and the Democrats have spent billions on concocting a proxy war with Russia by aggressively advancing NATO to its borders and have supported a genocidal war in GAZA by financing the Zionist aggression, back tracked on climate change, immigration reform, student debt, and medicare for all. Unionization has seen some major advances, the peace movement has been revitalized, and finance capitalism has pretty much recovered from the losses due to covid. Neo-fascism has made electoral and social advances and Biden has managed to become more unpopular than Trump. The CP is a small party and while it has basically supported most all the right causes and condemned the bad ones it has been mostly an observer of events vicariously participating in victories and defeats organized by others. This will continue to be the case until a new non-revisionist leadership comes to the fore which rejects Webbism, not just verbally but in practice, and puts forth a revolutionary Marxist-Leninist platform that rejects reformist pussy footing with the Democrats and begins to field candidates (not just talk about it) either in its own name or as independents or in real, rather then imaginary, coalitions in which its participation is public knowledge. This will be a difficult challenge as long as top down bureaucratic centralism rather than Leninist democratic centralism (not its Stalinist variant which proved unsuccessful) remains the modus operandi of a self perpetuating Webbite leadership. A Class Struggle Moment This section has two paragraphs. 1. The first notes an uptick of militancy in the labor movement and makes generalized statements about how the workers are for the progressive things we support and against the things we don’t. The GDD doesn’t seem to realize that the working class is not of one mind on the issues discussed. Some 40% of unionized workers support MAGA and 90% of the working class isn’t even unionized. What the GDD calls ‘’a new class struggle’’ is actually just a return to normalcy after the covid lockdown and the fact that many union contracts are expiring and negotiations are getting underway. It is important to support all progressive union struggles and demands, as well all organizing efforts but these struggles are not qualitatively different from normal union activity under capitalism. 2. This paragraph notes some interesting statistics that can make us hopeful for the future of the labor movement but they only show modest beginnings. The percentage of pro union Americans has reached the level it had in 1965 when union membership was over 30% of the workforce. Popularity is one thing but actual political and economic clout is another. Recently THE ATLANTIC pointed out ‘’Despite all the headlines and good feeling, a mere 10 percent of American workers belong to unions. In the private sector, the share is just 6 percent. After years of intense media attention and dogged organizing efforts, workers at Amazon, Starbucks, and Trader Joe’s still don’t have a contract, or even the start of meaningful negotiations to get one.’’—4/18/2024 While it’s good that 500,000 workers were involved in strikes and walkouts in 2021, we should remember in the 1970s almost every year saw 2,000,000 such labor actions. All this just means we can’t be complacent — we have a long way to go to really radicalize the consciousness of the workers and when that happens you won’t find any Genocide Joe presidents posing as ‘friends’ of labor. ANTI-MONOPOLY CONSCIOUSNESS In discussing this section in a Marxist context, not a revisionist one, we must distinguish anti-MONOPOLY from anti-monopoly CAPITALISM. Many groups are opposed to monopoly but have no interest in replacing capitalism with socialism. The article opens by pointing out that a majority of the public have ‘a dim view’ of big business. This is based on a Gallup poll which also mentions that this doesn’t apply to youth between the ages of 18-29 and that the greatest drop in big business support comes from conservative Republicans (no doubt due to big business becoming so-called ‘woke.’) We are also informed the masses ‘’are opposed to a single business dominating any given market and antitrust laws are popular’’. This has been the case, by the way, since at least the Teddy Roosevelt era. This is supposed to be a ‘’new moment in the class struggle’’ but these sentiments are as old as the hills and fluctuate back and forth all the time. The next fairly long paragraph lets us know the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer and capitalism isn’t working out for millions of people. This is pretty much a description of ‘capitalism through the ages.’ It would be nice if it did, work out for all and sundry but what’s important for the system is the rich are getting richer part. The system is working very well when the capitalists are rolling in clover and the devil takes the hindmost. That’s pretty much the system today and when we have the choice to pick one of two genocidal maniacs to be the president you have been living in an alternate reality to be seeing either a ‘’socialist moment’’ or a Great Leap Forward in the class struggle. Here is the evidence for the alternative reality. 1. Only 40% of Afro-Americans view capitalism favorably. This is cited from an article entitled ‘’Black Americans view capitalism more negatively than positively but express hope in Black businesses.’’ But also 52% had a positive view of socialism. As far as a socialist moment is concerned, 62% didn’t expect any real change in the system during their lifetime. 2. The GDD also cites that only 48% of women are favorable to capitalism. This is from the article ‘’Modest Declines in Positive Views of ‘Socialism’ and ‘Capitalism’ in U.S.’’ This article concludes, ‘’The American public continues to express more positive opinions of “capitalism” than “socialism,” although the shares viewing each of the terms positively have declined modestly since 2019.’’ No moment here. Finally, once again an incorrect Marxist view must be corrected. With respect to the problems of discrimination and lack of justice for the working class and especially minorities, including wage differentials, the GDD points out,’’Institutionalized racism and misogyny are clearly hard at work. They remain capitalism’s Achilles’ heel.’’ The first sentence is totally correct, but not the second. As pointed out earlier, racism and misogyny are features of the superstructure conditioned by historical context and cannot be the Achilles heel of capitalism. That would be its inability to appropriate surplus value from labor power due to the irreparable loss of markets. We can conclude from this section of the GDD there is enough discontent to give the left an opening to increase its influence in the country. Left grouplets backing Biden based on imaginary coalitions will probably not be in a position to benefit from this opening. Crisis of governance This section points out that there is a widespread dissatisfaction with the way the government is functioning. It maintains this is largely due to GOP intransigence but the Pew Research Center report behind this section found ‘’no single focal point for the public’s dissatisfaction.’’ Rather it was across the board ‘’widespread criticism of the three branches of government, both political parties, as well as political leaders and candidates for office.’’ However, this didn’t prevent people from going out to vote and the last three general elections had record turnouts. It seems that faith in the system is still working. The section concludes with a portrait of the Republican Party which is accurate and grim. The majority of Republicans have become ultra-right proponents of conspiracy theories, believe the 2020 election was ‘stolen’ by Biden, their support of the neofascist Trump does not bode well for the future of bourgeois democracy. While it is true that ‘’white supremacy, along with extreme nationalism, are driving this brand of politics’’ it fails to mention the real cause which is fueling these traditional right-wing features of American democracy— the worsening economic conditions created by the capitalist system supported by both major parties. The Stock Market is booming but Main Street is debt ridden, inadequately insured, faced with inflation, eroding living standards and despondent regarding the future. Neither of the two major political parties has viable solutions to these problems. This is affording a neofascist such as Trump a shot at returning to the White House. Supporting Biden is hardly a sign of a ‘’socialist moment,’’ Democratic, anti-racist majorities The very first paragraph is very problematic. It begins by saying ‘’ the threads of equality and democracy run deep in the fabric of the United States’ body politic and culture.’’ It seems to be just the opposite. The society was based on slavery and after the Civil War by cut throat industrial capitalism which even today leaves 90% of working people without union protections, minority rights are restricted and have only recently seen some relief with civil rights legislation enacted in the LBJ era. Women’s rights are a joke with inability to get the ERA passed, wage parity, and the Supreme Court, in addition to negating minority voter registration protections, has abolished the constitutional right of abortion. We are now engaged in a great culture war over sexual rights, voter rights, immigration rights, and the threat of a Neo-fascist being elected president. The evidence given by the GDD of this fabricated deep thread is 1. The Black Lives Matter uprising, 2.protests for LGBTQ and immigrant rights, 3. 2020 election of Biden and 2022 election (in which the Republicans actually took over the House— it was a close defeat so a ‘victory.’ The fact that elemental human rights, elemental equality, are NOT provided by our society and have to be constantly fought for and some need an uprising to get heard (this uprising resulted in increased funding for the police) indicates the authors have no understanding of the nature of the society they live in. The basic deep threads in this society are woven on the loom of monopoly capitalism and they are anti real democracy and equality for the masses and for strengthening the rule of law enacted for the benefits of capitalist domination and imperialist expansion. These real threads periodically call forth protests but when the dust settles and a few reforms are in place the fabric of capitalist domination remains firmly in place. Thus, after around 50 years of preaching left-center unity, bill of rights socialism and lesser evil voting, fascism is poised to take power. The second paragraph of this section gives some justification for a progressive majoritarian reading of current public opinion on the following issues— 1. Majority support for affirmative action. This is based on an article from the Cato Institute which actually maintains ‘’Polls do not produce a clear picture of where Americans stand on the issue.’’ So, it’s unclear where the majority stands according to this source. It’s good to remember that pollsters word polls to get the results they want. 2.The majority supports specifically equal affirmative action for women. The Gallup Poll behind this found 72% of women and 61% of men agreed. 3. A supermajority of non LGBTQ Americans support equal rights for the LGBTQ community according to a study released by GLAAD – ‘’the world’s largest Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer (LGBTQ) media advocacy organization.’’ The polls show these progressive trends but on the other hand, politically, they also show Trump leading Biden which indicates cognitive dissonance among the electorate, or the voters think Biden is a fake progressive. It is hard to think someone who backs, in fact enables, genocide and the cold blooded murder of over 14,000 children, is progressive or even fit to be president. The GDD is correct in maintaining these majoritarian progressive views are a good basis to build on to win over mass support. The rest of this paragraph just repeats what leftists have been saying over and over forever— victory depends on unity, we must support all the rightful demands of all oppressed groups, fight for peace, etc.,etc. It is certainly correct. It was correct in Deb's day and it still is. The GDD says this fight must be directed against the MAGA right and fascism. It says nothing in this section about socialism. Despite the fact that the Democratic Party leadership is supporting the GAZA genocide, starving our socialist comrades in Cuba, attacking every progressive anti-imperialist movement around the world, prolonging the proxy war against Russia, building up for a confrontation with China, and is the ruling party of the number one imperialist power in the world and the greatest enemy to the world’s oppressed masses, the GDD wants us to work with this child murdering genocidal party in what it calls ‘’the people’s front.’’ This to defeat the Republicans in 2024 and in the indefinite future. This is not Marxism-Leninism, siding with one group of imperialists to defeat another in a series of short term struggles marked by the bourgeois election cycle. Fighting fire with fire often results in bigger fires. Finally, the GDD asserts, ‘’Participation in it and helping activate the anti-fascist, anti-MAGA majority remains a top priority for the Communist Party in the coming period.’’ There may be other more important priorities. It is the Convention that is supposed to decide the top priorities but it has already been decided by the leadership what they will be. Our conventions have often been just show pieces for the leadership since by the use of slates and delegate selection their supporters always control the vast majority of votes and they remain in power regardless of the sentiments of the membership whose views, if too critical, are either censored or ignored. This is the way conventions were held in the Soviet Union and the former east European Socialist Countries, and one of the reasons they no longer exist. As long as the Webbite faction that controls the party continues this model for self perpetuation I fear our party will fail to gain a significant portion of influence on the left due a genuine Marxist-Leninist political formation. Well, who knows the future. I hope I am wrong and overly pessimistic and the party actually has a successful openly democratic convention and I wish the comrades the best in their deliberations. Sapere Aude! Toward a socialist moment 2.0 This is the last section of the GDD and it is not very clear as to what is meant by ‘socialism.’ What is the ‘’Bill of Rights socialist vision’’ that a working-class-led state will exemplify? The capitalist state already has a Bill of Rights. If we have a peaceful transfer of power it’s because the Bill of Rights of the capitalists helped us along. Are we going to change it or make a new one? Now it’s just a slogan we thought up to gain some attention and to assure people socialists won’t take away their rights. The KKK and the NAZI groups can still have rallies and marches ( or can they)? What does a working-class-led state imply— a transition to socialism and the abolition of the bourgeoisie as a class? That is what socialism means to Marxist-Leninists and if you are going to be honest about it the Bill of Rights won’t apply to the bourgeoisie. Sorry guys, it’s Bill of Rights SOCIALISM and one way or another you won’t be around. We are told how popular socialism is becoming ‘’close to a third of the U.S. people are open to the socialist idea.” What kind of socialism is that? It is ‘’Socialism as it’s understood in the popular imagination.” That’s Bernie Sanders socialism, e.g Denmark! The socialist tradition we historically represented is closer to East Germany. I doubt if one third of Americans are thinking of East Germany plus the Bill of Rights. This is where the 2.0 comes in. East Germany , the former Soviet bloc, Cuba, China and other socialist countries are 1.0 socialists.’’The socialist moment that emerged around the broad left in 2016 and 2020 must be built upon.’’ That is the tradition of the old Socialist Party of Norman Thomas, DSA and the eco-socialists of the Green Party and the movements coming out of the Bernie Sanders campaign. 1.0 is history and 2.0 is coming. The red caterpillar will become a multicolored butterfly (or perhaps a grey moth). The GDD says in effect, we have to build on the Bernie roots by applying Marxism-Leninism (this is a nod to party stalwarts who haven’t got with the program) creatively applied to U.S. conditions. This will become socialism 2.0. What we see is a program based on the ideas of Euro-communism and the evolutionary social democratic philosophy of the Second International as developed by Bernstein and, after 1914, Kautsky. This is the new dawn we are asked to embrace. I’m not saying it’s wrong or incorrect, it’s just not Marxism-Leninism and a party with this type of program may be the only way to press left for reforms in the U.S., but it should seriously consider changing its name as this is a program traditionally associated with the anti-communist left. Author Thomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. Tom is the Counseling Director for the Midwestern Marx Institute. He is the author of Reading the Classical Texts of Marxism (2022), Eurocommunism: A Critical Reading of Santiago Carrillo and Eurocommunist Revisionism (2022), The Outcome of Classical German Philosophy: Friedrich Engels on G. W. F. Hegel and Ludwig Feuerbach (2023), On Lenin's Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky (2023), and Early Christianity and Marxism (2024) all of which can be purchased in the Midwestern Marx Institute book store HERE. Archives May 2024

0 Comments