|

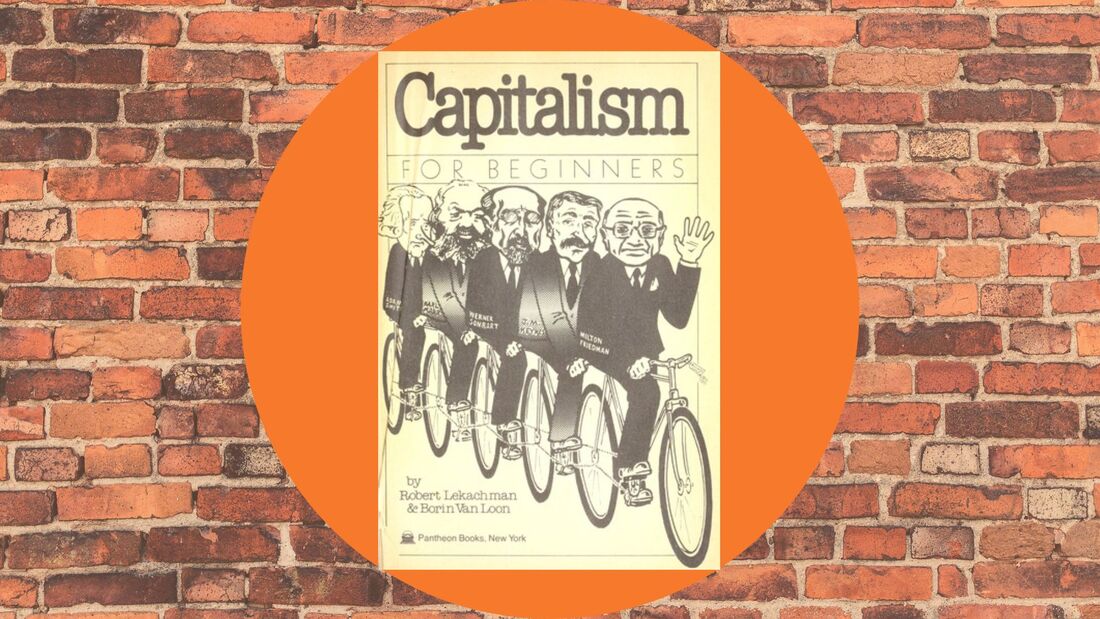

8/27/2022 Book Review: Robert Lekachman & Borin Van Loon – Capitalism for Beginners (1981)Reviewed By: Jymee CRead NowOne of the most crucial tasks in the movement for socialism and the general liberation of the proletariat is to hold a proper understanding of capitalism. How the system functions, its history, the arguments in its favor perpetuated by the ruling class, a strong grasp on these concepts works to ensure that we as socialists and communists are duly prepared to fight against the reactionary, hegemonic forces of capitalism on a global scale. Without such knowledge, without a solid understanding of the theoretical and historical foundations of capitalism, our fight is faulty and ultimately incomplete. The writings of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, and numerous others throughout history have provided integral analyses of capitalism, imperialism, and similar reactionary isms that stand in the way of constructing socialism. These are essential for all of us within the socialist movement to study, however, there do exist some challenges that may make studying these texts more difficult for someone. The density of the work (especially some of Marx’s writings), the lack of historical context, or even something such as having a learning disability can make studying these works a more difficult task for several people. Socialist economist Robert Lekachman’s 1981 book Capitalism for Beginners, with illustrations from Borin Van Loon, serves as a potential secondary tool in strengthening how capitalism is understood and what can be done to address the inherent issues within the system. Capitalism for Beginners provides a critical lens in the pursuit of educating readers on the ins and outs of capitalism from its historical foundation onward. The first third of this book is used as a platform to discuss, how capitalism has managed to maintain such a stranglehold on American economics, politics, and culture as it developed within the United States. In providing a brief overview of capitalism, Lekachman utilizes this brief description as a segway into addressing why socialism had not been able to muster a strong position within the US. Comparing the conditions of the United States and Europe, the myth of class mobility was born into the US, with the myth in question alongside the lack of a peasantry and other similar class positions being listed as some of the factors for the entrenching of capitalism into the roots of American society. The so-called “Invisible Hand” of capitalism is also touched upon. Lekachman continues with a more robust historical recap of capitalism’s formation within the USA. Beginning with an explanation of the mercantile system that capitalism sprouted from, moving on to the concept of the “free labor movement” along with the free market in general and acknowledging the influence of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, Lekachman continues by providing some poignant critiques of the free-market structure and practices. Though figures are dated given the time of publication, with many of these numbers coming from the late 1970s, the statistics provided regarding the various forms of inequality under capitalism provide a historical lens into the perpetual, inherent contradictions of the system. When speaking on the issue of income, Lekachman writes; “There are two ways of looking at the inequality of economic reward. The capitalist says that unequal income is essential to an efficient economy. Self-interest is an important impetus to effort, saving and investment. Besides, some people are brighter, more imaginative or energetic than others, so it’s only fair that their rewards should be higher. A socialist would argue that inequality reflects the power relationships of capitalism. Either way, inequality under capitalism is taken as necessary and inevitable.” Other contradictions addressed by Lekachman include the problem of inheritance, in addition to the reactionary gendered and racially driven inequalities promoted and perpetuated by the capitalist apparatus. The self-destructive nature of capitalism is further analyzed within this book, leading into further analysis of the development of 20th century capitalism surrounding the emergence of the theories of one John Maynard Keynes in the 1930s following the advent of Great Depression. Detailing the limited successes of Keynesianism, in addition to the goal of Keynesian economics of countering the influence of Marxism, Lekachman highlights that amid World War II and in its aftermath, Keynesian theory would introduce an economic boom period, especially in the first decades following the end of WWII. This boom, for both the US and much of Western Europe, proved to have limitations, though these limitations were on display more so in the United States. Keynesian theory and practice, in addition to western efforts such as the Marshall Plan and the establishing of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, allowed for countries such as Britain to enact an economic and governmental shift into a form of social democracy. The US, enjoying similar economic developments, lagged and continues to lag behind other developed countries in the construction a legitimate safety net in regarding to healthcare, social services, and other infrastructural aspects associated with the welfare-state of social democracy. Likewise, the instability of capitalism in all its forms became more apparent as economic growth remained uneven, and the strains of the illegal war in Vietnam allowed for the cracks in Keynesian to emerge. As contradictions became more and more apparent, Lekachman’s focus shifts from the rise of the Keynesian model to its fall, subsequently moving into the rise of neoliberalism, monetarism, and the mass privatization and austerity measures that came with it in the US, the UK, and elsewhere as a result of the recession of the early 1970s. Highlighting the era of Milton Friedman, Ronald Reagan, and Margaret Thatcher, we see a brief explanation of monetarism, shedding light on the vastly more prominent negatives of the system, particularly the promotion of austerity measures that lead to the privatization of necessary services and industries. In addition, we see the issue of people conflating something that has even the slightest resemblance to a welfare state with full on Soviet style socialism, using the monetarist, anti-Labour Party crusade in Britain after Thatcher’s election as an example. Other negative effects and falsehoods perpetuated by the system are likewise touched upon. Lekachman, although a socialist in his own right, provides a weak conclusion in addressing the neoliberal age of capitalism. At the end of this book, he states that the way to properly defeat capitalism is by replacing with a form of democratic socialism. While this is by no means an attack on those who consider themselves democratic socialists, the lack of adherence to historical conditions and contexts in his conclusion is not sufficient in truly addressing what needs to be done in successfully overthrowing the capitalist state apparatus. Gains can be made through the ballot box even if only incremental, but history and even modern conditions have proven that working solely or at least primarily through the electoral process as a means of building socialism will be likely met with more difficulties, setbacks, and unfortunately, failures in the attempt of socialist construction. Additionally, Lekachman inadvertently points out one of the flaws in his own goal. Prior to proclaiming the need for democratic socialism, Lekachman acknowledges the very possibility of corporations and other agents of capitalism turning to means in line with that of fascism and other more aggressive forms of the dictatorship of capital as a means of safeguarding their economic interests and swiftly curtailing the influence of unions, socialists, and other such demographics. That the capitalists would have such power in their inherent collaboration with the bourgeois state only shows that the difficulties of building socialism only or even primarily through the bourgeois democratic process are more apparent, with the strategy of democratic socialism having no real preparation for when the capitalist class triples down on the oppression of those fed up with the cycle of capitalism. Despite the faulty conclusion in how to counter the mechanisms of capitalism, Capitalism for Beginners does ultimately serve a good purpose in educating people on the history and inner workings of capitalism and its agents. Lekachman’s explanations of the various stages and aspects of capitalism from its rise out of mercantilism to the era of neoliberalism are informative while not being dense or explained in an overly complicated fashion. The visuals in this book also serve a multipronged purpose of being informative, driving a point forward with additional comments, and even just being mildly humorous. For instance, there’s an illustration of Milton Friedman as a scarecrow, a tongue-in-cheek way of calling Friedman a literal strawman. We also F.A. Hayek portrayed as a 1920s style gangster, a way of displaying how the monetarist, neoliberal system works in tandem with criminal or near-criminal acts committed often in line with the workings of the bourgeois government. Faulty conclusions and some dated figures aside, Capitalism for Beginners is a very thorough but easy to understand book that may serve as both an introductory piece and a refresher course for those aiming to garner a solid comprehension of capitalism. AuthorJymee C is an aspiring Marxist historian and teacher with a BA in history from Utica College, hoping to begin working towards his Master's degree in the near future. He's been studying Marxism-Leninism for the past five years and uses his knowledge and understanding of theory to strengthen and expand his historical analyses. His primary interests regarding Marxism-Leninism and history include the Soviet Union, China, the DPRK, and the various struggles throughout US history among other subjects. He is currently conducting research for a book on the Korean War and US-DPRK relations. In addition, he is a 3rd Degree black belt in karate and runs the YouTube channel "Jymee" where he releases videos regarding history, theory, self-defense, and the occasional jump into comedy https://www.youtube.com/c/Jymee Archives August 2022

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed