|

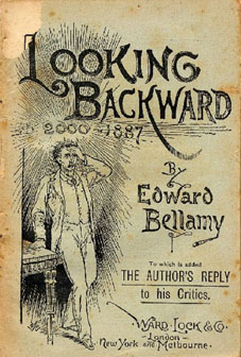

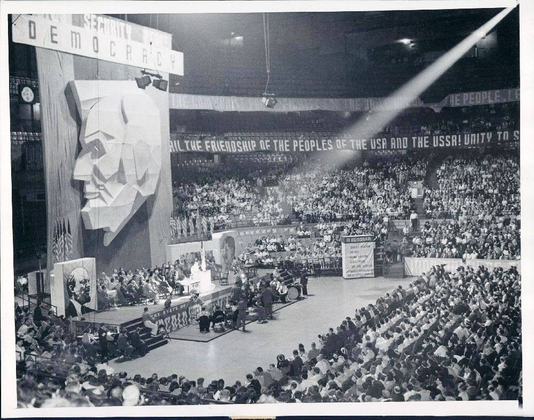

2/24/2021 Book Review: The Ghost of Plum Run: Vol. 1 - Beginnings By Timothy Russo. Reviewed By: Mitchell K. JonesRead NowA selection of Uncle Tom’s Cabin pottery circa 1850s According to legend, when United States President Abraham Lincoln met Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, he said to her, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war.” Whether, in fact, Lincoln really did say this is immaterial. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a best seller of the 1850s and 60s and it brought realistic depictions of the horrors of slavery into the homes of millions of white Americans who might have otherwise never imagined the atrocities committed on Southern plantations. Uncle Tom’s Cabin inspired songs, plays, fashion and even kitchenware. Many, including the Lincoln of legend, saw Stowe’s writing as the catalyst for the American Civil War. Lincoln’s purported comment illustrates the importance of stories. Stories are powerful. They can take the receiver of the story to a different place and time. They can reshape the receiver’s vision of what is moral, just and most importantly what is possible. What happens in reality can be guided by a committed group of individuals’ effective articulation of a good story. Italian critical theorist Antonio Gramsci called an effective story “a special relationship or bond between intellectuals and the people, the nation.” Fiction had a powerful effect on the politics of post-bellum America. Edward Bellamy’s utopian socialist novel Looking Backward: 2000-1887, published in 1888, was the third best seller of its time after Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Ben Hur. The novel articulated a vision of a future socialist America from the perspective of a Rip Van Winkle character who awoke to a much better world than the one that existed when he fell asleep. The story inspired its readers to take action to build the future Bellamy described. One hundred sixty five Nationalist Clubs, so called because they wanted to nationalize all industries after Bellamy’s description, sprung up throughout the United States by 1891. Others fused Karl Marx’s scientific socialism with Bellamy’s Nationalism and the American utopian movements of the 1830s and 40s to form prefigurative socialist communities such as the Kaweah Colony in California’s Sequoia region. The Bellamy movement led to the formation of the People’s Party, also known as the Populists, in 1892. The Populists became a major electoral force that pushed both the major parties to the left. Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, published in 1888 The members of the Marxist-Bellamyite Kaweah Colony pose in front of the “Karl Marx Tree” sequoia, circa 1890 In 1935 Georgi Dimitrov, at the Seventh Congress of the Comintern in Moscow, expressed the importance of creating stories that connect contemporary struggles to the revolutionary history of the past. He was concerned that reactionary historical narratives were dominating the public imagination, remarking: The fascists are rummaging through the entire history of every nation so as to be able to pose as the heirs and continuators of all that was exalted and heroic in its past, while all that was degrading or offensive to the national sentiments of the people they make use of as weapons against the enemies of fascism. Hundreds of books are being published in Germany with only one aim—to falsify the history of the German people and give it a fascist complexion. The new-baked National Socialist historians try to depict the history of Germany as if for the past two thousand years, by virtue of some historical law, a certain line of development had run through it like a red thread, leading to the appearance on the historical scene of a national 'savior', a 'Messiah' of the German people, a certain 'Corporal' of Austrian extraction. In these books the greatest figures of the German people of the past are represented as having been fascists, while the great peasant movements are set down as the direct precursors of the fascist movement. Inspired by Dimitrov’s sentiments, the Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA), under the leadership of Eric Browder, began to use the slogan “Communism is 20th Century Americanism” in order to link communist activities with the venerated revolutionary traditions of Thomas Paine and Abraham Lincoln. In their 1939 election platform they wrote, “Reactionaries of all shades cry out against socialism. They say it is revolutionary. True, the change to socialism will be revolutionary; but since when is revolution un-American? On the contrary, revolution is one of the most powerful traditions of our people who are among the most revolutionary in the world.” Tenth Communist Party USA convention in Chicago. May 1938. Fiction is a tool that has historically been wielded to great effect by both the right and the left. Some have argued more recently that the strength of the pro-Trump QAnon movement, its symbols very visible in the January 6th, 2021 Capitol seige, is that it offers a narrative, albeit delusional, to explain inexplicable hisotrical events. Hitler’s Jewish conspiracy narrative served this same purpose after the failure of the Weimar republic and the Sparticist revolution to uplift the German economy. On the other hand, the popularity of 2020 presidential candidate Bernie Sanders was largely due to his compelling narrative that described an ultra-rich 1% of the population that has exploited and oppressed the rest of the 99% of the people. The story remains a compelling and persistent legacy of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Occupy and Sanders’ narratives and the historical narratives of the broad left tend to have the benefit of being based on economic and historical facts. Radically reactionary, fascistic narratives like QAnon and the Jewish conspiracy are based almost entirely on fiction. Unfortunately, they proliferate because they are repeated so often. As Marx pointed out in his Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right, religion also serves this purpose. At times it is the “cry of the oppressed creature,” based on economic and historical realities. At other times it is “the opiate of the masses,” based on fictions repeated across centuries. Much of what Americans know about the Civil War was invented by former Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forest and his pro-slavery secret society, the Ku Klux Klan, shortly after the end of the Civil War. The “Noble Lost Cause” narrative, portrayed in popular films like Birth of a Nation (1915) and Gone With the Wind (1940), has dominated entertainment and sadly even scholarship relating to the American Civil War for over a century. To counter the Klan’s reactionary narrative, it is important for the political left to articulate a narrative about the heroic actions of radicals during this revolutionary historical period. Author Timothy Russo has taken on today’s task of creating an explicitly leftist narrative of the American Civil War that is, in part, fiction and, in part, based on actual historical events. In a note left for this reviewer, Russo writes, “I firmly believe the left needs to tell great stories.” Unlike the vast majority of Civil War fiction, Russo’s heroes are radicals: underground abolitionists, adventurist Marxists, Free Soil homesteaders and labor organizers. Russo seeks to uproot the untold story of the revolutionary generals, colonels and underground railroad conductors that has so often been written out of the history of the American Civil War. Russo’s protagonists echo the true stories of antebellum radicals like Marxist refugee of the Revolutions of 1848 Joseph Weydemeyer, abolitionist freethinker Sojourner Truth and spiritualist sisters Kate and Margaretta Fox. Russo’s focus is not on high ranking Republicans like John C. Frémont and Abraham Lincoln, but on common, working class and oppressed people: child laborers, Irish migrant workers, 48ers, strikers, Free Soil homesteaders, Quakers, religious freethinkers, clandestine gay men and temperance feminists. The world of Russo’s book is not the contemporary, atheistic world of today. It is an accurate portrayal of the way people saw the world at that time. Contemporary consumers of historical narratives often assume that the people of bygone eras were just like us, only with less technology. However, the world of 19th century American was a world where God was real, He was above us and the spirits were real and they were among us. Russo uses the idea of ghosts as a metaphor for a certain radical spirit. However, he is historically accurate in his portrayal of these ghosts as reified beings that have very real effects on the world and the people that inhabited it. Russo’s story is a complex, interconnected thriller that eventually leads to the outbreak of what the International Workingmen’s Association, under the leadership of Karl Marx, called “the American Antislavery War.” Ghosts of Plum Run is a compelling story whose protagonists are racially, nationally and age diverse. It takes place on the embattled frontier in what would become Minnesota. The book is full of action that makes the reader yearn to find out what happens next. Despite a few instances of awkward wording, Timothy Russo has succeeded in telling a “great story” from the left. Ghosts of Plum Run is a valuable contribution to the genre of historical fiction. Although Civil War fiction is somewhat of a saturated market, few Civil War novels tell the story of how the various elements of European radicalism, militant abolitionism, organized labor and Free Soil homesteading coalesced around the Republican cause in the lead up to the Civil War. Even fewer in the Civil War novel cannon tell the story from an explicitly socialist point of view. Russo reports that volume two of Ghosts of Plum Run will be coming out this Spring. This writer, for one, is anticipating the next chapter in this saga with baited breath Review AuthorMitchell K. Jones is a historian and activist from Rochester, NY. He has a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and a master’s degree in history from the College at Brockport, State University of New York. He has written on utopian socialism in the antebellum United States. His research interests include early America, communal societies, antebellum reform movements, religious sects, working class institutions, labor history, abolitionism and the American Civil War. His master’s thesis, entitled “Hunting for Harmony: The Skaneateles Community and Communitism in Upstate New York: 1825-1853” examines the radical abolitionist John Anderson Collins and his utopian project in Upstate New York. Jones is a member of the Party for Socialism and Liberation. If you are interested in reading The Ghost of Plum Run, you can purchase it HERE.

2 Comments

|

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed