|

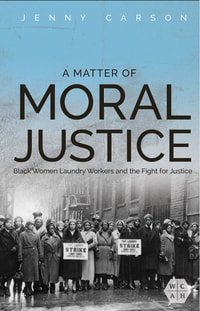

8/16/2021 Black women laundry workers finally get their due as organizers and leaders. By: Beatrice LumpkinRead NowA strike by the Laundry Workers Industrial Union. Featured on the cover of Jenny Carson's 'A Matter of Moral Justice', and in Julia Reichert's 1976 film, 'Union Maids'.

The right to organize was key to unionizing laundry workers for the first time way back in 1937. That right was guaranteed by the Wagner Act, passed just two years earlier in 1935. In 2021, the right to organize is again a key issue for workers and for the AFL-CIO, the country’s top labor union body. They are demanding that Congress pass the PRO Act—the Protect the Right to Organize Act. While only 11% of the U.S. labor force belong to unions, surveys have shown that 65% would join a union if they had the chance. There are lessons in Moral Justice for the next big organizing drive that the AFL-CIO is sure to launch as soon as the PRO Act passes. This reviewer has a personal reason to welcome Carson’s book. In 1937, I was on the team of CIO organizers working with laundry workers. Then I worked in laundries until 1941. Before Moral Justice was published, little had been written about laundry workers. Carson does a good job of exposing the extreme exploitation of laundry workers by their employers, with low wages, hard physical labor, bad working conditions, racism, and gender inequality all defining the industry. Black women and other women of color have made up the majority of laundry workers for the past 100 years. So it is fitting that Moral Justice centers on the fight for equality for women and for Black workers on the job and for full representation as leaders of the union. In covering laundry workers’ struggles through the stories of two Black women leaders, Carson has chosen inspiring subjects. Dolly Robinson grew up in North Carolina, moved to New York City at 13, and became a laundry worker and union activist at 15. Despite the hard days of work in the laundry, Robinson continued to take classes at night. At 24, she was appointed to the Laundry Workers Joint Board’s (LWJB) Education Department, becoming director at age 26. Charlotte Adelmond grew up in Trinidad, then part of the British West Indies. In 1924, she joined her sister in Harlem and found work in a laundry. The Garveyite movement was then strong in Harlem, and Adelmond joined, stirred by the militant Black Nationalist message. Soon, she settled in Brownsville, Brooklyn, and again found work in a laundry. She was a fearless defender of workers’ rights and a strong voice for equal rights for women as well as a fighter against racism. After the newly organized CIO laundry workers were taken over by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, Adelmond was elected business agent of Local 327. She was re-elected again and again, a tribute to her effective leadership. Adelmond and Robinson were at the heart of what Carson describes as “the extraordinary activism of a group of workers who, in the face of incredible odds, tried to build a democratic union committed to racial justice, economic dignity, and gender equality.” Carson begins the story with a look at the 1912 strike of inside laundry workers. From the early days of the power laundry industry, the owners had established racist and gender-based bars to the higher-paid jobs. The drivers who picked up the dirty wash and delivered the laundered clean linens and clothes were the highest paid. Only white men were hired as drivers. In the early 20th century, the AFL organized each trade separately. In 1912, the inside laundry workers who did the washing, ironing, and packing were organized in AFL locals that were separate from the laundry drivers and engineers. Black women were in the majority among inside workers. The strike of the inside laundry workers in 1912 is called an “uprising” by Carson. She explains that it was part of the same upsurge demanding “Bread and Roses” that formed the needle trades unions. The laundry strikers won the support of the Women’s Trade Union League, a middle- and upper-class organization that was well-financed. At a later date, the WTUL also supported the fight by Adelmond and Robinson for Black leadership and women’s equality. However, the 1912 laundry strike was lost, largely because the drivers continued to work. The need to unite all trades within a plant in the same union was a lesson learned by those who formed the CIO in 1935. That strategy was called “industrial unionism.” “Communist Laundry Organizing” is the title of chapter 5 in Carson’s book. Starting in the Bronx, a staff of 30 CIO organizers signed up tens of thousands of laundry workers in the Laundry Workers Industrial Union-CIO. As one of those organizers, I remember the number as 20,000 and that half of the organizers were Communists. As supporters of industrial unionism, Communist Party members had earlier taken the lead to organize a Laundry Workers Industrial Union. In a way, that gave them a head start when the CIO started its organizing drive among laundry workers in 1937. But on the company side, the owners did not want to negotiate contracts with a fighting laundry workers union. At this point, the all-white leadership of the ACWA clothing workers union used its clout with the national CIO to “take over” the newly-organized laundry workers union and its 20,000 members. Soon, the democratic culture of the Laundry Workers Industrial Union—a culture that empowered the membership—was replaced by top-down decision-making by ACWA officials. Naturally, the workers fought back to defend union democracy, but they were not united. Another hindrance was the fact that the whole country was in the grip of anti-communist hysteria by 1939. Anti-communist attacks did not end until the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor forced the U.S. to ally with the Soviet Union in World War II. In the poisonous atmosphere of those pre-Pearl Harbor days, the officers and business agents of local 328 were put on trial—me included. The charge against us said nothing about our work in the union. The only “charge” was that we were Communists. Some of us were and some were not; that was a false issue. We had been elected because we fought for the rights of laundry workers. All of us were found “guilty” by the two judges, top national officers of ACWA. We were then expelled from the union and our local was placed in receivership. Meanwhile, another fight for laundry union democracy was going on elsewhere in the union, led by Charlotte Adelmond, business agent of local 327. The ACWA-appointed manager began appointing local officers instead of allowing the laundry locals to continue to elect them. Often, elected Black officers were replaced by white appointees. In 1941, Adelmond publicly accused the manager of racism and was punished with three months suspension as business agent. She won her job back, thanks to her members’ support and influential friends. Both Adelmond and Robinson continued the fight for Black representation and women’s rights until 1950. Then, both were forced out of the union, ending Adelmond’s many years of fighting for laundry workers. Fortunately, Dollie Robinson had continued her studies, winning a law degree. In 1956, she became the New York State Commissioner of Labor. Both women helped lay groundwork for the renewed civil rights upsurges in the 1960s and to date. Carson clearly exposes the contradiction between the public statements and the practice of the social democratic leadership of ACWA, now renamed Workers United. After 1937, they controlled the Laundry Workers Joint Board, their affiliate. In public, these union leaders, all white, spoke up against racism and in defense of women’s rights. But in practice, they actively prevented qualified Black leaders from rising to the top of the laundry workers union whose membership was majority Black and female. Without representative top leadership, without empowering the union membership, the union did not have the strength needed to stop the extreme exploitation of laundry workers at the hands of the laundry owners’ association. In Carson’s chapter 5, she featured the work of Jessie Taft Smith in developing the fight against racism and kindly includes my work as well. Taft Smith had been my mentor in the CIO’s Laundry Workers Industrial Union. Carson quotes her throughout the book because of Taft-Smith’s knowledge of the laundry industry and union. Also, Taft Smith lived to 100 and was available for interviews. Moral Justice mentions but does not explain, the Communist campaign against remnants of racism inside the Communist Party itself. This campaign educated white as well as Black members. Mark Naison, in his Communists in Harlem During the Depression, neatly sums it up: “The drama of the Yokinen trial [August Yokinen, a CP member accused of making racially disparaging remarks – B.L.] had impressed upon white Communists, in no uncertain terms, that it was their duty as Communists ‘to march at the head of the struggle for Negro rights’.” The Communist Party’s prioritizing of the fight for Black equality played a key role in developing the civil rights movement of the 1930s and 40s. That movement centered around the fight to save the lives of Angelo Herndon and the Scottsboro Nine. Carson’s book shows that laundry workers were deeply involved in all of these struggles that paved the way for the Black Lives Matter Movement of today. I believe that the attempts to build a fighting, democratic union of laundry workers would have had a better outcome in 1941 if there had been unity between the Communist-led forces and the Adelmond-Robinson forces. But that would have taken willingness on the part of both groups. This need for left unity, also left-center unity, remains an important challenge for labor to this day. A Matter of Moral Justice: Black Women Laundry Workers and the Fight for Justice By Jenny Carson University of Illinois Press Hardcover, paper, and e-book editions AuthorBeatrice Lumpkin is a long time labor activist with laundry workers, steelworkers, and teachers. As a math professor at Malcolm X College in Chicago, she fought to restore the contributions of people of color to the educational curriculum. She has served as a multicultural consultant to textbook publishers and to public schools in Chicago, Detroit, Milwaukee, and Portland, Ore. She is the author of “Always Bring a Crowd, the story of Frank Lumpkin Steelworker” and “Joy in the Struggle, My Life and Love.” Beatrice Lumpkin is an active member of the Teachers Union and SOAR. This article was produced by People's World. Archives August 2021

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed