|

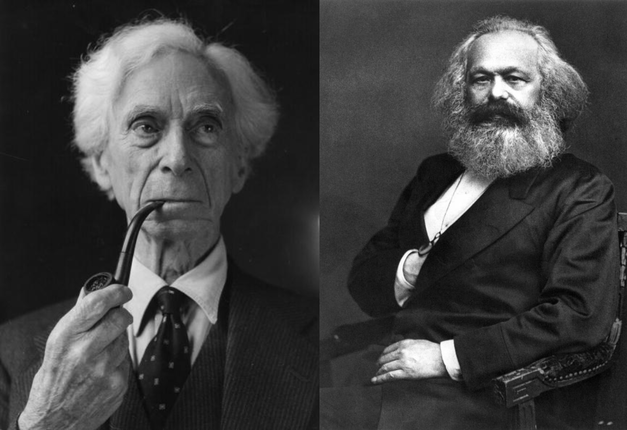

Bertrand Russell discusses the philosophy of Karl Marx in chapter 27 of his A History of Western Philosophy (HWP). He begins by telling us he is not going to deal with his economics or politics, just his philosophy and its influence on others. While Lenin saw Marx’s philosophy as developing from three sources— British economic theory, early French socialist thought, and classical German philosophy (Hegel) Russell sees only two sources. Marx’s philosophy is the “outcome” of “the Philosophical Radicals (mostly British) and French materialism. He credits Marx with a broad outlook, at least with respect to Western Europe where he shows “no national bias.” But, Russell says, it’s not the same regarding Eastern Europe because “he always despised the Slavs.” A comment about this. This meme about the Slavs was widespread in anti-Marxist and anti-Soviet propaganda (and still is) in the time of the writing of the HWP. It has no basis in fact. Marx and Engels made highly critical, even derogatory, remarks about some groups of Slavs in the Austrian Empire who fought on the reactionary Austrian aide in putting down the progressive forces leading the 1848-49 pan-European anti-feudal revolution. But they were in full support of the Polish revolutionaries at that time, and later supported the progressive revolutionary forces that were developing in Russia. After this maladroit observation, Russell continues in a more positive vein. He does mention economics, saying Marx’s economic philosophy is an outgrowth of classical British thought on this subject, in agreement with Lenin. There is a difference, however, the British economists wrote in defense of the up and coming industrialists and were opposed to the interests of the agriculturalists and the laboring classes. I should mention, though, that Adam Smith did have a lot to say in defense of the laboring classes and criticized their treatment by the up and coming industrialists. Marx, on the other hand, was completely on the side of the wage-earners. He never relied on emotional appeals when he laid out his theories and, Russell says, “he was always anxious to appeal to evidence, and never relied on any extra-scientific intuition.” Russell next discusses Marx’s “materialism”. It’s not the mechanical materialism of the French enlightenment. In which external objects react on a passive human consciousness. Russell points out that under the influence of Hegel, Marx’s materialism is an interaction between the subject and object in which both are changed — it’s what’s meant by the term “dialectical.” Russell says this view is similar to what non-Marxists refer to as “instrumentalism”. This will not do. It is too subjective as instrumentalism, a form of pragmatism, judges the truth of a statement by its usefulness— true statements do not necessarily relate to some objective x in-itself but they are statements that are useful for our future actions and ability to understand or control reality as it appears to us. Let’s deconstruct the following quote. “In Marx’s view, all sensation or perception is an interaction between subject and object; the bare object, apart from the activity of the percipient, is a mere raw material, which is transformed in the process of becoming known”. The problem with this is that it reeks of Kantianism. The raw material is the thing-in-itself which is transformed by perception into the thing-for-us. The mind is much too active here. Marxists have used the analogy of a mirror in discussing the relation of subject and object— perception is a “reflection” of the external world. Perception doesn’t change the object. The mind is not totally passive as experience is the collection of all our perceptions and the mind has to order and evaluate them so as to understand the world it reflects. The world itself is in constant motion and change. The concept of “dialectics” is used to describe this aspect of reality, it doesn’t impose dialectics on the objects, it reflects the workings of the objectively existing dialectical motions exhibited in the external world. There is no spoon bending telekinesis going on. Russell gives a long quote from Marx ending with “Philosophers have only interpreted the world but the real task is to alter it.” It’s a quote from his Theses on Feuerbach. It’s a famous quote, but it is beside the point regarding the transformation/reflection theories of perception as acting on our percepts to change aspects of external reality follows from either theory. Russell next asserts that “It is essential to this theory [Marxism] to deny the reality of “sensation” as conceived by British empiricists.” This empiricist conception of ‘sensation” was a revolutionary new development, Russell says, introduced into philosophy by John Locke (1632-1704). The mind is originally a blank slate (tabula rasa) and all our ideas are based on sensations as input from the five senses (experience, perception) which are then put into order by an internal power of the mind or “reflection” (our thoughts, and ideas) called internal perception. There are no innate ideas. Russell admits both empiricism and idealism have technical philosophical problems that are still today unresolved. This stems from a view that external objects have some kind of unchanging essence that the brain passively accepts and then fools around with by means of reflection. He says Marx has a more activist view of the interaction between the world and the brain, but he won’t discuss this further in this chapter but will deal with it in a later chapter. That turns out to be the chapter on Dewey and his view of “instrumentalism” mentioned above. Russell says that Marx didn’t spend a lot of time on these concerns and so he intends to move on to Marx’s views on “history.” Russell tells us that Marx’s philosophy of history is a “blend” of Hegel plus classical British economy. He takes the dialectic from Hegel but interprets it materialistically not idealistically as Hegel does. He tells us that the “matter” in Marx’s version of materialism is “matter in the peculiar sense that we have been considering, not the wholly dehumanized matter of the atomists.” It’s true that Russell was describing a “peculiar” kind of matter above when discussing perception as a “mutual” interaction between subject and object, but he is wrong in saying this was Marx’s view. Matter is the objectively existing material world that exists whether humans exist or not— it was here before humans evolved and will be here when humans are extinct. But while we are here, we have to understand it to survive and prosper and science is the best method we have found to do so. Philosophy prospers when it incorporates the findings of science, religion when it ignores or denies them. Russell next takes up Marx’s “materialist conception of history”. Basically, the main features of the art, religion, and philosophy (and culture in general) of any epoch are “the outcome” of the economic mode of production and distribution by which society maintains and reproduces itself. I think Marxists would prefer “conditioned by” rather than Russell’s “the outcome of”. Russell only accepts some of the features of this view which he adopted in writing the HWP, but he rejects the thesis “as it stands.” He will illustrate what he means by considering Marx’s thesis as applied to the history of philosophy. All philosophers think their philosophy is “true”. No one would bother to write philosophy if they thought it was just some time-conditioned ultimately irrational product of their particular environment and not objectively but just subjectively “true”. He says, “Marx, like the rest, believes in the truth of his own doctrines; he does not regard them as nothing but the expression of the feelings natural to a rebellious middle class German Jew who was born in the middle of the nineteenth century.” So, what can we make of this? Well, Russell does think the ideas of an epoch do generally reflect the socio-political background— those of Aristotle and Plato were “appropriate” to city states, the Stoics to “cosmopolitan despotism,” medieval scholasticism to the Catholic Church, those of Descartes and Locke to “the commercial middle class” and Marxism and Fascism to the modern industrial State. Russell believes this to be important and true. The above seems like a form of elementary Marxism that hasn’t really been thought out very well. Nevertheless it’s the part of Marx that Russell says he gets. He does, however, say there are two major objections he has to Marxism. First, Russell rejects economic determinism as he thinks “wealth” is less important than “power” as the motivating force of history. Since he has already written a book about this (Power, 1938) he refers us to it and will not deal with this topic here. Neither will I, as Marxism is not based on economic determinism which is trotted out by anti-Marxists in order to refute a misinterpretation of Marxism and think Marxism itself has been refuted. Second, having disposed of “economic determinism”, Russell looks at other theories of “social causation” used to explain history; he doesn’t exactly mention any by name but wants to argue that personal reasons, temperament, emotional attachments, etc. make any general theory of social causation moot. He picks some very special technical issues in philosophy (the problem of universals, the ontological argument, the truth or not of materialism) and says, contra Marx, that he thinks that it’s a waste of time to look for economic reasons to explain the positions of the different philosophical opinions on these issues. Marx would agree. Marx would agree because his sub/super structure distinction, that the laws, values, moral outlooks, art, religious views (the superstructure of ideas and institutions) are in general conditioned by the physical environment people inhabit which affects how they make their living— obtain food, social wealth, living arrangements, etc. (the substructure). People living in a Stone Age environment are not going to build the Empire State Building. A Gothic cathedral is not going to be built by animists. The superstructure also feeds back influences on the substructure so there is mutual interaction between them. Marx never advocated the simple one-way determinism or social causation which upsets Russell. As far as “materialism” goes, the following comments should cover Russell’s views. 1) Russell says the word has many meanings, but he has shown above that Marx “altered” the traditional meaning. I already pointed out how Russell was in error about this. 2) The problem with using this word is that people have “avoided” defining what they mean by it. 3) Depending on the definition materialism can be a) proven to be false, b) may be true but “there is no positive reason to think so”, c) there are some reasons to believe it, but they are not conclusive. Since b and c are basically the same there are just two responses needed. Response to 2. In Marxism the distinction between Materialism and Idealism boils down to the view about the existence of external objects— does the Universe depend upon the existence of the human brain and consciousness in order to exist or is it independent on the human consciousness and existed before there were any conscious beings or ideas at all— say at the time of the “Big Bang” and the millions and billions of years before any type of life at all emerged in the universe? If you believe the Universe and matter (the quarks, photons, etc.,) existed before humans then, for a Marxist, you are a materialist. If you believe there was some great big Consciousness before the Big Bang, and it caused the Big Bang (and waited around 13.5 billion years or so before deciding to make humans or whatever) you are not. Response to 3. Russell says Big Bang Materialism may be true “but there is no positive reason to think so.” I think the modern results of the scientific view of the origin of the Universe are positive enough. It may be the case that the science of the future replaces the “Big Bang” with a different explanation, but I don’t think the replacement will claim that the Universe was dependent on humans. There are two “different elements” referred to by the word “philosophy.” One involves scientific knowledge and technical expertise in which a great deal of mutual agreement is possible. The other is the social area where the ruling element is “passionate interest” and reason takes a backseat— here is where, Russell says, Marx’s insights are “largely true.” Author Thomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. He is the author of Reading the Classical Texts of Marxism and Eurocommunism: A Critical Reading of Santiago Carrillo and Eurocommunist Revisionism. Archives June 2023

2 Comments

Ross Coyle

6/30/2023 11:35:35 pm

Would it be correct to say that one can be materialist in Marx's sense if one recognises the prior non-differentiation of humans and the cosmos/nature, that becomes a question of interiority/exteriority only when self-consciousness arises with it's bifurcation of subject and object?

Reply

Charles Brown

7/7/2023 08:07:47 am

Marx is “pro-Slav “ here ( smiles) https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/ni/vol08/no10/marx-zas.htm

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed