|

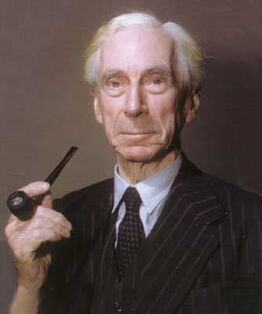

This short book [Bertrand Russell in 90 Minutes by Paul Strathern, Chicago, Ivan R. Dee, 2001] of 92 pages is one of many (24 at the time it was published) in Strathern’s 90 Minutes series. If you know absolutely nothing about Russell, perhaps the greatest English speaking philosopher (bourgeois) of the 20th century, you could begin with this book – but you will need more than it provides to really understand Russell. Nevertheless, if Russell is a stranger this isn’t a bad first meeting. Russell (1872-1970) was both a technical philosopher in the empiricist tradition (Locke, Hume, Mill) and a socially engaged activist – most famously in the “Ban the Bomb Movement”, co-founded with Einstein, of the 1950s and 1960s. He also co-chaired, with Jean Paul Sartre, the war crimes tribunal that exposed the Nazi like criminal behavior of the US in Vietnam, although Strathern doesn’t mention this. Russell got the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1950. His best known popular works are A History of Western Philosophy (1945), “Why I am Not A Christian” (1927), and The Problems of Philosophy (1912). Strathern’s short introduction made me a little cautious since he refers to Wittgenstein as “the philosopher who succeeded to his mantle.” This is not an apt comment as Wittgenstein was the moving force behind a philosophical school not endorsed by Russell (ordinary language analysis). No one really succeeded to Russell’s mantle. Strathern does point out the three great passions that Russell always said drove his life, “the longing for love, the quest for knowledge, and heart-rending pity for the suffering of humanity.” He also points out that Russell’s philosophy was rooted in a scientific world outlook. I think, however, he misrepresents Russell when he writes that he “sought to establish a demonstrably certain logical philosophy....” Russell maintained that philosophy, like science, was always provisional and dealt with probabilities not “demonstrably certain” knowledge. I think Strathern confused Russell’s empirically based philosophy with his early attempt to deduce arithmetic from logic in Principia Mathematica (co-authored with A. N. Whitehead). Russell was one of the founders of modern mathematical logic. Actually, philosophy was the no man’s land between what we can reliably know (science) and bull shit (religion and related ways of thinking). Philosophy is the set of beliefs we hold until they end up in the former or are consigned to the latter two divisions. The heart of this book is the 63 page essay “Russell’s Life and Works.” Strathern describes how Russell, who was educated at Cambridge, revolted against the prevailing neo-Hegelian idealism he found at the university and developed a philosophy based on logical analysis which he later called “logical atomism” because it stressed the discreteness of things rather than seeing them as all interrelated parts of the neo-Hegelian “Absolute.” The best part of this book is Strathern’s explanation of Russell’s Paradox [consider the set of all sets that are not members of themselves; such a set appears to be a member of itself if and only if it is not a member of itself] and his Theory of Types [ to deal with this paradox]. He presents these technical topics that Russell dealt with in mathematical class theory in an easily understandable way so that lay readers can follow the arguments that took place in early 20th century philosophy of mathematics and logic. Unfortunately, Strathern does not present Russell’s mature philosophy. After the excellent mathematical exposition he gives an overview of Russell’s thought based on works from which he later diverged. This is especially the case with the 1912 The Problems of Philosophy. Strathern should have consulted Russell’s 1959 My Philosophical Development where he gives his final views on many of the topics discussed in the 90 Minutes book. Russell may need more than ninety minutes! This later book is also a good intro Russell”s thought. Strathern barely mentions Russell’s political views just noting The Theory and Practice of Bolshevism, Russell’s diatribe against the Russian Revolution (which also, paradoxically, has great things to say about it) and he never points out Russell’s misreading of Hegel and Marx which mar his reputation as an historian of philosophy. He also relies too much on Ray Monk’s biography of Russell – which he calls “superb, possibility definitive” without pointing out that many, if not most, Russell scholars react negatively to Monk’s work. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. Archives August 2021

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed