|

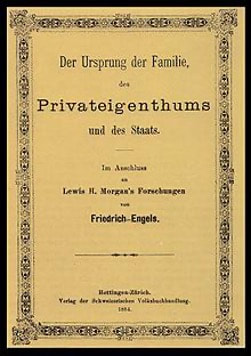

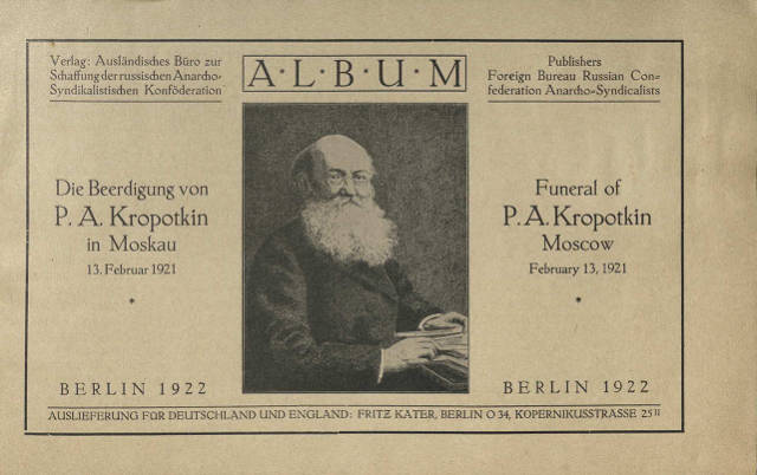

4/28/2022 Before Class Struggle: Primary Communism, Human Nature and Mutual Aid. By: Mitchell K. JonesRead NowLonghouse at Ganondagan State Historic Site, Boughton Hill, Victor, NY. Haudenosaunee means “people who build a house." Communists often hear the objection that communism can never work because it is against humanity's essentially greedy, selfish human nature. But is human nature really essentially greedy? Karl Marx and Frederick Engels argued that human nature evolved along a dialectical trajectory based on conflict over material resources. In light of this view, their bold proclamation in the 1848 Communist Manifesto that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle” begs the question: What came before class struggle, before hitherto existing society?[1] In the Manifesto, Marx and Engels sketched out a path of social evolution that continues to influence historical materialists today. They wrote: In the earlier epochs of history, we find almost everywhere a complicated arrangement of society into various orders, a manifold gradation of social rank. In ancient Rome we have patricians, knights, plebeians, slaves; in the Middle Ages, feudal lords, vassals, guild-masters, journeymen, apprentices, serfs; in almost all of these classes, again, subordinate gradations. They described historical epochs, ancient, feudal and bourgeois, characterized by the complex relationships of oppressors to oppressed. However, it would not be until Engels’ book The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, published in 1884, that Engels attempted to explain what came before hitherto existing society, before the history of class struggle. Engels wrote The Origin of the Family using Marx’s notes for a book Marx had planned to write about the work of anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan around the time of his death in 1883. Engels described the pre-society, pre-class struggle period as primitive communism. Today the less Eurocentric term primary communism is more appropriate. According to anthropologists, this period has made up over 99 percent of human history.[3] What can this history before society, before class struggle teach us about human nature and the potential for the revolutionary transformation of society today? Lewis Henry Morgan Morgan’s book League of the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois. The cover of the original 1884 German edition of On the Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State acknowledges Morgan’s influence on the front cover. Pioneer anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan was the first to identify the political economy of the extensive pre-class period as “primitive communism.” Morgan was a profound influence on Marx and Engels’ anthropological thought. Engels praised Morgan in the preface to the first edition of his book The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State published in 1884: For Morgan in his own way had discovered afresh in America the materialistic conception of history discovered by Marx forty years ago, and in his comparison of barbarism and civilization it had led him, in the main points, to the same conclusions as Marx. And just as the professional economists in Germany were for years as busy in plagiarizing Capital as they were persistent in attempting to kill it by silence, so Morgan's Ancient Society received precisely the same treatment from the spokesmen of “prehistoric” science in England.[4] Much later socialists such as Sam Marcy, founder of the communist Workers’ World Party would use the less pejorative term “primary communism.” Marcy wrote in 1992, “Lewis Henry Morgan's writings on the communal life of the Iroquois in North America confirmed what the socialist movement in Europe had deduced about early societies elsewhere before written history: that there was a universal period when property was communal, there was no state, and the products of human labor were shared equitably.”[5] In 1851 Morgan published the League of the Ho-De-No-Sau-Nee, Or Iroquois, which became a founding text of ethnography, the scientific study of cultural customs. Morgan discovered that the Haudenosaunee had practiced “communism in living” for centuries.[6] Haudenosaunee society planned for and met the needs of each individual. Extended families lived communally in large longhouses and shared their belongings in common. They organized inter-communal trade networks based on reciprocity. In 1881, Morgan wrote: Among the Iroquois hospitality was an established usage. If a man entered an Indian house in any of their villages, whether a villager, a tribesman, or a stranger, it was the duty of the women therein to set food before him. An omission to do this would have been a discourtesy amounting to an affront. If hungry, he ate; if not hungry, courtesy required that he should taste the food and thank the giver. This would be repeated at every house he entered, and at whatever hour in the day.[7] Hospitality and harmony were key values in Haudenosaunee society. Engels explained the conditions that made primary communism possible: A division of the tribe or of the gens into different classes was equally impossible. And that brings us to the examination of the economic basis of these conditions. The population is extremely sparse; it is dense only at the tribe’s place of settlement, around which lie in a wide circle first the hunting grounds and then the protective belt of neutral forest, which separates the tribe from others. The division of labor is purely primitive, between the sexes only. The man fights in the wars, goes hunting and fishing, procures the raw materials of food and the tools necessary for doing so. The woman looks after the house and the preparation of food and clothing, cooks, weaves, sews. They are each master in their own sphere: the man in the forest, the woman in the house. Each is owner of the instruments which he or she makes and uses: the man of the weapons, the hunting and fishing implements, the woman of the household gear. The housekeeping is communal among several and often many families. What is made and used in common is common property — the house, the garden, the long-boat.[8] Key to Engels’ interpretation of Morgan was Morgan’s discovery of matrilineal society where the family lineage is traced through the female line. Marcy explained, “Primary communism based on food gathering and hunting succumbed to private ownership because it lacked the necessary concentration and development of the means of production. But private property, while more productive, also brought subjugation and degradation, first of women.”[9] The overthrow of matrilineal society signaled the beginning of inequality and class society according to Engels: The overthrow of mother-right was the world historical defeat of the female sex. The man took command in the home also; the woman was degraded and reduced to servitude, she became the slave of his lust and a mere instrument for the production of children. This degraded position of the woman, especially conspicuous among the Greeks of the heroic and still more of the classical age, has gradually been palliated and glossed over, and sometimes clothed in a milder form; in no sense has it been abolished.[10] Engels saw Morgan’s discovery so key to understanding the origins of inequality that he wrote in the preface to the 1884 fourth edition of Origin of the Family: This rediscovery of the primitive matriarchal gens as the earlier stage of the patriarchal gens of civilized peoples has the same importance for anthropology as Darwin’s theory of evolution has for biology and Marx’s theory of surplus value for political economy. It enabled Morgan to outline for the first time a history of the family in which for the present, so far as the material now available permits, at least the classic stages of development in their main outlines are now determined. That this opens a new epoch in the treatment of primitive history must be clear to everyone. The matriarchal gens has become the pivot on which the whole science turns; since its discovery we know where to look and what to look for in our research, and how to arrange the results. And, consequently, since Morgan’s book, progress in this field has been made at a far more rapid speed.[11] Engels considered Morgan’s work as groundbreaking as Darwin’s. Indeed, many of Engels’ conclusions in The Origin of the Family were as influenced by Darwin’s theories as they were by Morgan's. When Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species was first published in 1859 it caused a sensation in the academic world. Scientists, biologists and philosophers interpreted Darwin's evolutionary model in different ways. Social Darwinism was a belief that the strong survive through natural selection and that this idea should be applied to humankind as much as Darwin applied it to the rest of nature. Social Darwinism came to dominate North American social theory in the 1870s. Social Darwinism really had little to do with Darwin. In fact, conservative Anglican Thomas Robert Malthus’ Essays on Population established the idea that “on the whole, the best live,” an idea which influenced Darwin’s concept of natural selection.[12] It was social Darwinist theorist Herbert Spencer that actually coined the term “survival of the fittest.”[13] Social Darwinists argued that society was rightly dominated by the powerful because they were the best of society. They argued that competition was the rule of success, not cooperation. Social Darwinism has been used to justify eugenics, imperialism, capitalism and eventually fascism. However, others combined Darwin’s theory of evolution with other kinds of evidence from zoology and anthropology and derived very different conclusions. Russian anarchist, zoologist and theorist Peter Kropotkin argued in 1902 that mutual aid, reciprocal exchange for mutual benefit, not competition and violence, was a key factor for evolutionary success. Kropotkin wrote: As soon as we study animals -- not in laboratories and museums only, but in the forest and the prairie, in the steppe and the mountains -- we at once perceive that though there is an immense amount of warfare and extermination going on amidst various species, and especially amidst various classes of animals, there is, at the same time, as much, or perhaps even more, of mutual support, mutual aid, and mutual defense amidst animals belonging to the same species or, at least, to the same society.[14] Kropotkin listed many examples of intra- and inter-species mutual aid in the animal world and concluded, “The animal species, in which individual struggle has been reduced to its narrowest limits, and the practice of mutual aid has attained the greatest development, are invariably the most numerous, the most prosperous, and the most open to further progress.”[15] He cited a study done by a Russian zoologist Karl Kessler who concluded that “all classes of animals, especially the higher ones, practise mutual aid” using empirical evidence collected from burying beetles, birds and mammalia.[16] Humans were no exception. Kropotkin concluded, “It is evident that it would be quite contrary to all that we know of nature if men were an exception to so general a rule: if a creature so defenseless as man was at his beginnings should have found his protection and his way to progress, not in mutual support, like other animals, but in a reckless competition for personal advantages, with no regard to the interests of the species.”[17] Although leader of the Russian Revolution Vladimir Lenin and Kropotkin disagreed on tactics, the two agreed that communism was the right course for humankind. Kropotkin said upon meeting Lenin: How glad I am to see you, Vladimir Ilyich! You and I have different views. We have different points of view about a whole series of problems, both as far as the execution and organization is concerned, but our goals are the same and what you and your comrades are doing in the name of communism, pleases me very much and makes my already aging heart happy.[18] Lenin was so impressed by Kropotkin’s work that approved a state funeral in Moscow for Kropotkin in 1921 and allowed anarchists to march and carry anti-Bolshevik banners.[19] Funeral of P.A. Kropotkin in Moscow, February 13, 1921: album Recent research has proven Kropotkin’s statement to be true of the earliest of human ancestors. Anthropologists Tim White, Gen Suwa and Berhane Asfaw discovered the Ardipithecus ramidus, one of the earliest human ancestors not shared with chimpanzees, in the Afar region of Ethiopia 1994. Their discovery was dated to about 4.5 million years ago. The discovery of Ardipithecus ramidus shed light on the trajectory of human evolution when compared with that of one of our closest relatives, the chimpanzee. Chimpanzee teeth have what is called a honing-complex, which means they have long canines that are used to rip apart tough meats. Homo sapiens and Ar. ramidus do not have a honing complex. The canines of Ar. ramidus are significantly “feminized,” meaning they are not sexually dimorphic. Sexual dimorphism is when species develop traits specific to the male or female sex. Smaller canine teeth indicate that the Ar. ramidus likely exhibited significantly less male-male aggression, when compared with primates like chimpanzees. A lesser degree of sexual dimorpohism could also mean a greater amount of equality between the sexes. Suwa et al write, “The dental evidence leads to the hypothesis that the last common ancestors of African apes and hominids were characterized by relatively low levels of canine, postcanine, and body size dimorphism. These were probably the anatomical correlates of comparatively weak amounts of male-male competition, perhaps associated with male philopatry and a tendency for male-female codominance as seen in P. paniscus and ateline species.”[20] This evidence indicated that the earlier work of primatologists like Jane Goodall, who tried to make inferences about human nature from studies with chimpanzees and other aggressive ape species, was less relevant to human nature since decreased aggression seems to be what set the human line apart from the apes. The human evolutionary line appears to indicate that parental investment, cooperation and gender equality, not competition and violence, were at least partially responsible for the evolutionary adaptations like upright walking and larger brain size that contributed to the formation of more complex modern Homo sapiens. The anthropologist Alfred Radcliffe-Brown applied Kropotkin’s concept of mutual aid to his ethnological and ethnographic work in the 1930s. He said of Kropotkin’s influence, “Like other young men with blood in their veins, I wanted to do something to reform the world – to get rid of poverty and war, and so on. So I read Godwin, Proudhon, Marx and innumerable others. Kropotkin, revolutionary, but still a scientist, pointed out how important for any attempt to improve society was a scientific understanding of it.”[21] Radcliffe-Brown studied kin relationships in South Africa and found that joking was one way to defuse potentially disruptive behavior. He wrote, “The show of hostility, the perpetual disrespect, is a continual expression of that social disjunction which is an essential part of the whole structural situation, but over which, without destroying or even weakening it, there is provided the social conjunction of friendliness and mutual aid.”[22] He also proposed that the primary factor in the maintenance of society is not governmental pressure, but social pressure. He wrote, “A social relation does not result from a similarity of interests, but rests either on the mutual interest of persons in one another, or on one or more common interests, or on a combination of both of these…. [W]hat is called conscience is thus in the widest sense the reflex in the individual of the sanctions of society.”[23] Radcliffe-Brown acknowledged, as Kropotkin did, that cooperation and mutual aid drove social evolution through collective responsibility, not coercive force. Other anthropologists have suggested the origins of trade and material exchange were not the result of greed and competition, either, but the result of the law of reciprocity. Reciprocity is mutually beneficial exchange without immediate reward. It is also known as gift economy. The French anthropologist Marcel Mauss wrote on gift-giving economy in his book The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies. In it he wrote, “In Scandinavian civilization, and in a good number of others, exchanges and contracts take place in the form of presents; in theory these are voluntary, in reality they are given and reciprocated obligatorily.”[24] He described the process of gift giving as potlatch, using the North American Chinook term. Anthropologist Frans Boas demonstrated the meaning of potlatch by quoting Chief O'wax̱a̱laga̱lis of the Kwagu'ł of British Columbia for his 1888 article “The Indians of British Columbia”: We will dance when our laws command us to dance, we will feast when our hearts desire to feast. Do we ask the white man, 'Do as the Indian does'? No, we do not. Why, then, will you ask us, 'Do as the white man does'? It is a strict law that bids us to dance. It is a strict law that bids us to distribute our property among our friends and neighbors. It is a good law. Let the white man observe his law; we shall observe ours. And now, if you are come to forbid us to dance, begone; if not, you will be welcome to us.[25] Mauss describes the potlatch tradition as universal amongst archaic societies. In the Maori culture of New Zealand, for example, all goods possess a spiritual power that is exchanged along with the gift. This spiritual power is called hau and the physical gift is called tonga. A Maori juridical expert explained it best in Mauss’ book: The tonga and all gods termed strictly personal possess a hau, a spiritual power. You give me one of them, and I pass it on to a third party; he gives another to me in turn, because he is impelled to do so by the hau my present possesses. I for my part, am obliged to give you that thing because I must return to you what is in reality the effect of the hau of your tonga.[26] This system of reciprocity was a form of exchange that predated both barter, direct trade, and mercantile, trade for currency, exchange. In his conclusion Mauss was optimistic about the elevation of the social over the individual. He wrote, “The brutish pursuit of individual ends is harmful to the ends and the peace of all, to the rhythm of their work and joys – and rebounds on the individual himself.”[27] He then critiqued capitalism, saying that under the contemporary system men are turned into machines forced to exchange their labor for less than its true value. He argued that the workers of all societies and historical epochs expected to be fairly rewarded for their efforts, and that the individualistic type of economy did not do this. He stated that there was self interest in gift giving, but it is only self interest in the sense that what is good for the whole is good for the individual.[28] Another French anthropologist, Pierre Clastres, wrote about the institution of the chief and his role in mutual aid and gift giving. In his book Society Against the State, published in 1974, Clastres studied the Guaraní and Chulupi of Paraguay and Argentina and the Yanomami peoples of Venezuela and Brazil. He wrote that chiefs in so-called “Indian” societies of South America were required to give most of what they had for the greater good of the community. Clastres argued there were no societies without political power, but there was a difference between coercive power and non-coercive power. He wrote, “The model of coercive power is adopted… only in exceptional circumstances when the group faces an external threat.”[29] Normally, civil power was based on consensus and its function was pacification. The chief existed to maintain the peace and harmony of the group.[30] The chief was required to give up his belongings to help the greater good of the community. Therefore, greed and power were incompatible. In this way the chief was not so much a ruler, but a servant of the people. Italian communist theorist Antonio Gramsci argued that there were two main factors at play in the maintenance of a society: the state and civil society. The state was a coercive apparatus represented by the violent dictatorship of the military, police and carceral apparati. Civil society was the realm of soft power, dominated by the social and cultural hegemony of the ruling class that legitimized that class’s domination.[31] However, there was another force, that of counter-hegemony, that existed in the realm of the proletariat. This kind of hegemony existed in subversion of the ruling class. Gramsci argued that a permanent proletarian hegemony must exist to oust the bourgeoisie, the ruling class of bourgeois or capitalist society.[32] Clastres argued the chiefdoms of South America had achieved a healthy balance between hegemony and counter-hegemony. He wrote, “It is in the nature of primitive society to know that violence is the essence of power. Deeply rooted in that knowledge is the concern to constantly keep power apart from the institution of power, command apart from the chief.”[33] In his conclusion he writes, “…what the Savages exhibit is the continual effort to prevent chiefs from being chiefs, the refusal of unification, the endeavor to exorcize the One, the State.”[34] Anthropologist Marshall Sahlins argued in his book Stone Age Economics, published in 1972, that while industrial society attempted to achieve affluence through producing much, primary communist society actually achieved affluence through desiring little. Sahlins based his claims on data from two contemporary hunter gatherer societies: the Arnhem Landers of Australia and the Dobe Bushmen of Kalahari Africa. His most surprising claim was that the average amount of time spent in the procuring of food for these primary communists was about four to five hours a day. The rest of their time was spent in leisure and sleep activities.[35] Despite problems with Sahlins’ data and conclusions, his theory of “original affluence” turned hunter gatherer society from a painful life of toil to an enviable, easy life of leisure and affluence in anthropological discourse.[36] Data from anthropologists suggests the opposite of the social Darwinist and “objectivist” claim that human nature is essentially greedy. In fact, the research of anthropologists reveals that the vast majority of human history was stateless, egalitarian and communal. Mutual aid, reciprocity and communal kinship bonds, not greed, completion and violence, prompted the first leaps in human evolution. If humanity had communism for most of its history we can have communism again. According to Sam Marcy, “The discovery of the early communist societies refuted the canard assiduously cultivated by apologists for the bourgeoisie: that a planned society is utopian, that humankind cannot plan its own society on the basis of common ownership of the means of production and equitable distribution of the products of labor. People had done just that for hundreds of thousands of years.”[37] [1] Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, “Manifesto of the Communist Party,” Communist Manifesto (Chapter 1), https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch01.htm#007. [2] Marx and Engels, Communist Manifesto. [3] Richard B. Lee and Richard Daly, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Hunters and Gatherers, (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 1. [4] Frederick Engels, “Preface to the First Edition, 1884,” Origins of the Family- Preface (1884), https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1884/origin-family/preface.htm. [5] Sam Marcy, “Soviet Socialism: Utopian or Scientific - Utopian socialist experiments,” https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/marcy/sovietsocialism/sovsoc1.html. [6] Morgan, Houses and House-Life of the American Aborigines, 44. [7] Lewis Henry Morgan, Houses and House-Life of the American Aborigines, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1881), 45. [8] Engels, The Origin of the Family. [9] Marcy, “Soviet Socialism.” [10] Ibid. [11] Frederick Engels, “Preface to the Fourth Edition, 1891,” Origins of the Family. Preface (1891), https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1884/origin-family/preface2.htm. [12] Gregory Claeys, “The ‘Survival of the Fittest’ and the Origins of Social Darwinism.” Journal of the History of Ideas. 61.2 (2000): 223. [13] Claeys, “The Survival of the Fittest.” [14] Peter Kropotkin, Mutual aid: A factor of evolution, 1902,, https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/kropotkin-peter/1902/mutual-aid/ch01.htm. [15] Kropotkin, Mutual Aid. [16] Ibid. [17] Ibid. [18] Vladimir Bonch-Bruyevich, “A meeting between V.I. Lenin and P. A. Kropotkin,” accessed January 22, 2022, https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/kropotkin-peter/1917/a-meeting.html. [19] Emma Goldman, Living My Life, (New York: Dover Publications, 1970), 867. [20] Gen Suwa et al., “Paleobiological Implications of the Ardipithecus Ramidus Dentition,” Science 326, no. 5949 (February 2009): pp. 69-99, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1175824. [21] George W. Stocking Jr., After Tylor, British Social Anthropology, 1888–1951, (Madison, Univ Wisconsin, 1995), 305. [22] Richard J. Perry, “Radcliffe-Brown and Kropotkin: The Heritage of Anarchism in British Social Anthropology,.” Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers, 51-52, (1975): 63. [23] Perry, “Radcliffe-Brown and Kropotkin,” 63. [24] Marcel Mauss, The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies, Trans. W. D. Halls, (London: W. W. Norton, 1990), 3. [25] Franz Boas, "The Indians of British Columbia," The Popular Science Monthly, March 1888 (vol. 32), p. 631. [26] Marcel Mauss, The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. Trans. W. D. Halls, (London: W. W. Norton, 1990), 11. [27] Mauss, The Gift, 77. [28] Ibid., 77 [29] Pierre Clastres, Society Against the State, Trans.: Robert Hurley and Abe Stein, (New York: Zone Books, 1987), 30. [30] Ibid., 30 [31] Dominic Mastroianni, “Hegemony in Gramsci,” https://scholarblogs.emory.edu/postcolonialstudies/2014/06/20/hegemony-in-gramsci/ [32] Pozo, Luis M. “The Roots of Hegemony: The Mechanisms of Class Accommodation and the Emergence of the Nation-people.” Capital and Class. 91. (2007): 55-89. [33] Clastres, Society Against the State, 154. [34] Ibid., 218. [35] Marshall David Sahlins, Stone Age Economics, (Chicago: Aldine-Atherton, 1972). [36] A key objection to Sahlins’ conclusion is that he did not factor food preparation into the “food question” calculations he did on the Dobe !Kung and Arnhem Landers. David Kaplan, “The Darker Side of the ‘Original Affluent Society,’” Journal of Anthropological Research 56, no. 3 (2000): pp. 301-324, https://doi.org/10.1086/jar.56.3.3631086. [37] Marcy, “Soviet Socialism.” AuthorMitchell K. Jones is a historian and activist from Rochester, NY. He has a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and a master’s degree in history from the College at Brockport, State University of New York. He has written on utopian socialism in the antebellum United States. His research interests include early America, communal societies, antebellum reform movements, religious sects, working class institutions, labor history, abolitionism and the American Civil War. His master’s thesis, entitled “Hunting for Harmony: The Skaneateles Community and Communitism in Upstate New York: 1825-1853” examines the radical abolitionist John Anderson Collins and his utopian project in Upstate New York. Jones is a member of the Party for Socialism and Liberation. Archives April 2022

3 Comments

Charles Brown

4/29/2022 10:31:46 am

Excellent!

Reply

Charles Brown

4/29/2022 10:37:12 am

http://take10charles.blogspot.com/2021/12/is-human-nature-social-or-selfish.html

Reply

Charles Brown

4/29/2022 10:40:39 am

http://take10charles.blogspot.com/2021/04/homo-communis.html

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed