|

8/22/2021 The Real Reason why Socrates is Killed and why Class Society Must Whitewash his Death. By: Carlos L. GarridoRead NowThe killing of Socrates left a stain on the fabric of Athenian society, a stain it nearly expanded 80 years later with similar threats of impiety towards an Aristotle determined not to let Athens “sin twice against philosophy.” This original sin against philosophy has been immortalized in philosophy classrooms for millenniums to come – turning for philosophy the figure of Socrates what for Christian theology is the figure of Jesus. A variety of interpretations concerning the reasons for his sentencing have since arose. The most dominant, though, is that Socrates was killed because of impiety. This interpretation asserts that Socrates was corrupting the youth by shifting them away from the God’s of the state and towards new divinities and spiritualities. This hegemonic reading of his death relies almost exclusively on a reading of Socrates as solely a challenger of the existing forms of religious mysticism in Athens. This essay argues that this interpretation is synechdochal – it takes the part at the top layer to constitute the whole (as if one could explain pizza merely by talking about the cheese). Instead, the death of Socrates is political – he is killed because he challenges the valuative system necessary for the smooth reproduction of the existing social relations in Athens. This challenge, of course, includes the religious dimension, but is not reducible to it. Instead, as Plato has Socrates’ character assert in the Apology, the religious accusation – spearheaded by Meletus – will not be what brings about his destruction. Our access to the trial of Socrates (399 BCE) is limited to Plato’s Apology of Socrates and Xenophon’s Apology of Socrates to the Jury. Out of these two, Plato’s has remained the most read, in part because Xenophon was not in Athens the day of the trial (making his source secondary), and in part because of the immense prominence of Plato in the history of philosophy. To understand the death sentence, we must thus turn to Plato’s Apology. The Apology is one of Plato’s early works and the second in the chronology of dialogues concerning Socrates’ final days: Euthyphro (pre-trial), Apology (trial), Crito (imprisonment), and Phaedo (pre-death). Out of the Apology arise some of the most prominent pronouncements in philosophy’s history; viz., “I am better off than he is - for he knows nothing, and thinks that he knows. I neither know nor think that I know” and “the life which is unexamined is not worth living.” Philosophy must thank this dialogue for the plethora of masterful idioms it has given us, but this dialogue must condemn philosophy for its unphilosophical castration of the radical meaning behind Socrates’ death. In the dialogue Socrates divides his accusers into two groups – the old and the new. He affirms from the start that the more dangerous are the former, for they have been around long enough to socialize people into dogmatically believing their resentful defamation of Socrates. These old accusers, who Socrates states have “took possession of your minds with their falsehoods,” center their accusations around the following: Socrates is an evil-doer, and a curious person, who searches into things under the earth and in heaven, and he makes the worse appear the better cause; and he teaches the aforesaid doctrines to others. Before Socrates explains what they specifically mean by this inversion of making the “worse appear the better,” he goes through the story of how he came to make so many enemies in Athens. To do this he tells us of his friend Chaerephon’s trip to Delphi where he asks the Pythian Prophetess’ whether there was anyone wiser than Socrates – to which they respond, “there was no man wiser.” The humble but inquisitive Socrates sought out to prove he could not have been the wisest. He spoke to politicians, poets, and artisans and found each time that his superior wisdom lied in his modesty – insofar as he knew he did not know, he knew more than those who claimed they knew, but who proved themselves ignorant after being questioned. Thus, he concluded that, Although I do not suppose that either of us knows anything really beautiful and good, I am better off than he is - for he knows nothing, and thinks that he knows. I neither know nor think that I know. This continual questioning, which he considered his philosophical duty to the Gods, earned him the admiration of the youth who enjoyed watching his method at work and eventually took it upon themselves to do the same. But it also earned him the opposite of youthful admiration – the resentment of those socially-conceived-of wise men who were left in the puzzling states of aporia. His inquisitive quest, guided by an egalitarian pedagogy which freely (as opposed to the charging of the Sophists) taught everyone, “whether he be rich or poor,” earned him the admiration of many and the condemnation of those few who benefitted from having their unquestioned ‘knowledge’ remain unquestioned. After explaining how his enemies arose, without yet addressing what the old accusations referred to by saying he made the “worse appear the better cause,” he addresses the accusation of Meletus, which spearheads the group of the new accusers. It is Meletus who condemns Socrates from the religious standpoint – first by claiming he shifts people away from the God’s of the state into “some other new divinities or spiritual agencies,” then, in contradiction with himself, by claiming that Socrates is a “complete atheist.” Caught in the web of the Socratic method, Socrates catches the “ingenious contradiction” behind Meletus’ accusations, noting that he might as well had shown up to the trial claiming that “Socrates is guilty of not believing in the gods, and yet of believing in them,” for, after a simple process of questioning, this is ultimately what Meletus’ charges amount to. Socrates thus asserts with confidence that his destruction will not be because of Meletus, Anytus, or any of these new accusers focusing on his atheism. Those which will bring about his destruction, those which from the start he asserted to be more dangerous, are those leaders of Athenian society whose hegemonic conception of the good, just, and virtuous he questioned into trembling. Having annulled the reason for his death being the atheism charges of Meletus and the new enemies, what insight does he give us into the charges of the old, who claim he made the “worse appear the better cause?” He says, Why do you who are a citizen of the great and mighty and wise city of Athens, care so much about laying up the greatest amount of money and honor and reputation, and so little about wisdom and truth and the greatest improvement of the soul, which you never regard or heed at all? Are you not ashamed of this? This passage gets at the pith of his death sentence – he questions the values of accumulating money, power, and status which dominated an Athens whose ‘democracy’ had just recently been restored (403 BCE) after the previous year’s defeat in the Peloponnesian War (404 BCE). This ‘democracy,’ which was limited to adult male citizens, created splits between the citizens, women, children, foreigners, slaves, and semi-free laborers. Nonetheless, the citizen group was not homogenous – sharp class distinctions existed between the periokoi – small landowners who made up the overwhelming majority in the citizen group; the new wealthy business class which partook in “manufacturing, trade, and commerce” (basically an emerging bourgeois class); and the aristoi – a traditional aristocracy which owned most of the land and held most of the political offices. The existing ruling ideas, determined by the interests and struggle of the aristocracy and emerging bourgeois class, considered the accumulation of money, power, and status to be morally good. These values, integral to the reproduction of the existing social relations of Athens, were being brought under question by Socrates. Socrates was conversing indiscriminately with all – demonstrating to rich, poor, citizen and non-citizen, that the life which pursues wealth, power, and status cannot bring about anything but a shallow ephemeral satisfaction. In contrast, Socrates would postulate that only a life dedicated to the improvement of the soul via the cultivation of virtue can bring about genuine meaning to human life. This is a complete transvaluation of values – the normative goodness in the prioritization of wealth, power, and status has been overturned by an anthropocentric conception of development, that is, a conception of growth centered around humans, not things. Socrates, then, is not just killed because he questions religion – this is but one factor of many. Instead, Socrates is killed because he leaves nothing unexamined; because he questions the hegemonic values of Athenian society into demonstrating their shamefulness, and in-so-doing proposes a qualitatively new way of theoretically and practically approaching human life. He does not call for a revolutionary overthrow of the aristocracy and for the subsequent installation of a worker’s city-state in Athens, but he does question the root values which allow the Athenian aristocracy to sustain its position of power. Socrates was killed because, as Cornel West says of Jesus, he was “ running out the money changers.” With this understanding of Socrates’ death sentence, we can also understand why it must be misunderstood. Socrates’ condemnation of Athenian society, if understood properly, would not limit itself to critiquing Athenian society. Instead, it would provide a general condemnation of the money-power driven social values that arise when human societies come into social forms of existence mediated by class antagonisms. Socrates is taught to have been killed for atheism because in a secularized world as ours doing so castrates his radical ethos. If we teach the real reason why Socrates died, we are giving people a profound moral argument, from one of the greatest minds in history, against a capitalist ethos which sustains intensified and modernized forms of the values Socrates condemns. In modern bourgeois society we are socialized into conceiving of ourselves as monadic individuals separated from nature, community, and our own bodies. There is an ego trapped in our body destined to find its “authentic” self in bourgeois society via the holy trinity of accumulating wealth, brand name commodities, or social media followers. Society provides little to no avenues for an enduring meaningful life – for, human life itself is affirmed only in the inhuman, in inanimate objects. Only in the ownership of lifeless objects does today value arise in human life. The magazine and newspaper stands do not put on their front covers the thousands of preventable deaths that take place around the world because of how the relations of production in capitalism necessarily turn into vastly unequal forms of distributions. Instead, the deaths of the rich and famous are the ones on the covers. Those lives had money, and thus they had meaning, the others did not have the former, and thus neither the latter. Today Socrates is perhaps even more relevant than in 399 BCE Athenian society. As humanity goes through its most profound crisis of meaning, a philosophical attitude centered on the prioritization of cultivating human virtue, on the movement away from the forms of life which treat life itself as a means, significant only in its relation to commodities (whether as producer, i.e., commodified labor power or as consumer), is of dire necessity. Today we must affirm this Socratic transvaluation of values and sustain his unbreakable principled commitment to doing what is right, even when it implies death. The death of Socrates must be resurrected, for it was a revolutionary death at the hands of a state challenged by the counter-hegemony a 70-year-old was creating. Today the Socratic spirit belongs to the revolutionaries, not to a petty-bourgeois academia which has participated in the generational castration of the meaning of a revolutionary martyr’s death. Notes [1] Louise Ropes Loomis, “Introduction,” In Aristotle: On Man in the Universe. (Classics Club, 1971)., p. X. AuthorCarlos L. Garrido is a philosophy graduate student and professor at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. His specialization is in Marxist philosophy and the history of American socialist thought (esp. early 19th century). He is an editorial board member and co-founder of Midwestern Marx and the Journal of American Socialist Studies. Archives August 2021

6 Comments

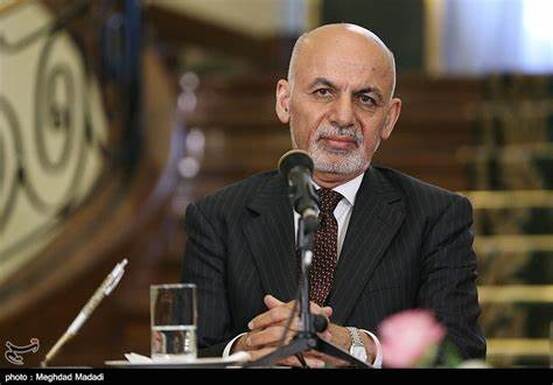

Featured image: Mercenaries working together with the US Army somewhere in the Middle East. Photo courtesy of AP. People frequently refer to Colombia as “the coffee-growing country,” due to its high volume of coffee exports, but in recent years Colombia has found itself in headlines for a different commodity. For example, a recent BBC article was titled “Mercenaries: Colombian Export Product.” In Iraq, Yemen, Libya, Haiti, Venezuela and now also in Afghanistan, there are great numbers of Colombian mercenaries. They perform their nefarious services in all of these disparate lands. The expansion of Colombia’s culture of death is no longer surprising for neighboring Venezuelans. This dreadful growth caused many to turn to murder for hire, a situation is of course instigated by the real economic crisis that all of Colombia is suffering. Companies for war Not only does the United States send regular troops to participate in its military invasions, but also hires “military security companies,” mercenaries subcontracted from various parts of the world for illegal armed invasions. Their use frees North America from responsibility for war crimes, as well as the “security company” itself, placing the responsibility solely with the hitmen in question. “So many intersecting factors—like those commonly found in the Middle East—including Colombia’s poverty, make the country ideal for mercenary operations,” noted Jorge Mantilla, a criminal investigator from the University of Illinois. In this way, Colombians are taken advantage of by these profiteers of war, who recruit both criminals and former soldiers of the Colombian Army. The internal war, funded from drug trafficking by the state of Colombia, contributes to the reality that guns are found in the hands of many Colombians on a daily basis. Because of this ease of access, civilians and ex-military men become mercenaries anywhere in the world. More than six decades of guerrilla war involving military, guerrilla groups and paramilitary forces has exacerbated the culture of violence in Colombia, creating the perfect breeding ground for one of the biggest exporters of mercenaries and violence in the world, all this with the complacent inaction of Colombian authorities. In the armed events in Afghanistan, many shocking things happened. However, despite its remoteness, one of them was very shameful in particular: confirmation that many Colombian mercenaries served United States’ interests in the war. The seriousness of these facts is magnified by the participation of Colombian mercenaries in coups, invasions, assassination and regicides, all of which are completely legal, according to the US or Colombia. In this manner they receive protection and even encouragement from the government of Bogotá, a powerful stimulus for those who choose this horrible profession. (RedRadioVE) by Eduardo Toro, with Orinoco Tribune content Translation: Orinoco Tribune AuthorOrinoco Tribune This article was republished from Orinoco Tribune. Archives August 2021 8/21/2021 Why America Needs Union Workers to Rebuild the Nation’s Infrastructure. By: Tom ConwayRead NowNew ornate streetlights add charm and ambience to Knoxville, Tennessee, even as they help the city dramatically slash energy consumption and save millions of taxpayer dollars each year. These high-tech lights last for years, require almost zero maintenance and provide better illumination than the old models, leading one grateful official to say they “raised the bar and changed the game” for a city seeking a brighter future. The United Steelworkers (USW) launched a weeklong bus tour on August 16 to call for historic investments in America’s infrastructure and to underscore the importance of using union-made materials and products, like the lights Knoxville installed, for these much-needed rebuilding projects. The multistate event, part of the union’s “We Supply America” campaign, included a stop at Holophane’s plant in Newark, Ohio. There’s where members of USW Locals 525T, 4T and 105T manufacture lighting products that not only illuminate Knoxville and other cities but also help to preserve vital supply chains across the economy. “We pretty much light the world,” said Local 525T President Steve Bishoff, noting he and his coworkers also supply state highway departments, shipping terminals, sewer authorities, energy facilities and military installations, along with numerous industries in the U.S. and overseas. “All the glass is made right here.” Bishoff strongly supports President Joe Biden’s American Jobs Plan, which would modernize the country and supercharge the economy with long-overdue investments in roads, water systems, communications networks and other infrastructure. He views the Senate’s bipartisan passage of a $1 trillion infrastructure bill on August 10 as an important step in achieving this progress and wants the House to quickly get to work on its own legislation. However, he knows that these bold investments will deliver the maximum benefits for America’s economy and security only if union workers lead the way. An infrastructure program with domestic procurement requirements “would bring more jobs here,” Bishoff said, noting upgrades to bridges, school buildings and other facilities would dramatically increase demand for Holophane’s products. An influx of new workers would help the greater Newark community, he added, noting the USW’s contract provides good wages and benefits that enable his coworkers to lead middle-class lives and support local businesses. He also has other important reasons for insisting that union workers drive the infrastructure upgrades. Upgraded roads and other improvements will only be as strong and dependable as the materials that go into them. Union members have the skills and dedication to build infrastructure that will be safe to use and stand the test of time. Officials in Knoxville, for example, chose lighting products made by Bishoff and his colleagues because of the reliability, brightness and safety they bring to streets, highways and other city-owned spaces. Similarly, the Tennessee Valley Authority chose Holophane’s union-made products to ensure the efficient operation of a gas plant crucial for power needs. And the ports of Los Angeles and Seattle installed Holophane’s lighting systems to maximize safety and productivity at two of the nation’s biggest shipping terminals. One port official in Seattle noted that the new lights turned darkness into daylight. That’s the kind of compliment Bishoff and his colleagues often hear. “It’s kind of a long process,” Bishoff, who’s worked at the plant for 44 years, said of the mixing, curing and craftsmanship that go into their top-quality production. “It takes teamwork to do it.” Shortages of face masks, hand sanitizer and other critical goods during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed the withered state of American manufacturing and exposed gaping holes in the nation’s supply chains. Carrying out infrastructure improvements with union-made components will help to sustain companies like Holophane, where Bishoff and his coworkers manufacture the kinds of items the nation relies on every day. But Biden’s plan will also stimulate additional manufacturing capacity throughout the economy and help to fill out supply chains, ensuring the nation never again has to rely on imported goods needed for everyday life or emergencies. It’s essential that America maintain the capacity to produce lenses, bulbs and light fixtures for highways, tunnels, airports and shipping terminals. It’s just as critical that the U.S. be able to supply the raw materials, manufacture parts and assemble finished products for numerous other infrastructure and industrial uses. The USW launched its “We Supply America” campaign to shine a light on the highly skilled union workers who are eager to deliver new infrastructure, a more powerful economy and stronger national security. In addition to Newark, the bus tour includes stops at Cleveland-Cliffs steel mills in Indiana and West Virginia, a Goodyear tire factory in Virginia and Corning’s optical-fiber plant in North Carolina. USW members like those at Cleveland-Cliffs produce the steel that America relies on not only for bridges, school buildings and drinking-water systems but also for shopping centers, athletic complexes and a vast array of consumer goods. Union workers at Goodyear and similar companies make the tires that keep passenger vehicles and tractor-trailers rolling, while also powering the cranes, graders and other heavy equipment essential for construction work. And USW members at Corning turn glass into optical fiber that’s the brains of cutting-edge broadband systems that help to connect Americans to business and educational opportunities. “It’s nice to be part of this,” Bishoff said of a union workforce that powers so much of the nation’s economy. Now, America has an unprecedented opportunity to harness that skill and passion to build not only better infrastructure but also a stronger, more prosperous country. “It would be good for everyone,” Bishoff said. AuthorTom Conway is the international president of the United Steelworkers Union (USW). This article was produced by the Independent Media Institute. Archives August 2021 On August 15, 2021, Afghan president Mohammad Ashraf Ghani made an inglorious exit from Afghanistan. In the words of Russian Embassy spokesman in Kabul Nikita Ishchenko: “the collapse of the regime…is most eloquently characterized by the way Ghani fled Afghanistan. Four cars were full of money, they tried to stuff another part of the money into a helicopter, but not all of it fit. And some of the money was left lying on the tarmac.” Sitting safely in the United Arab Emirates, he has busied himself with public relations damage control. “Do not believe whoever tells you that your president sold you out and fled for his own advantage and to save his own life…These accusations are baseless... and I strongly reject them…I was expelled from Afghanistan in such a way that I didn't even get the chance to take my slippers off my feet and pull on my boots.” Many high-ranking individuals have strongly disagreed with Ghani’s attempted dignification of his dishonorable escapade. On August 18, 2021, Afghan Defense Minister Bismillah Khan Mohammadi called on Interpol to arrest him for “selling out the motherland.” On the same day, Afghanistan’s ambassador to Tajikistan told a news conference that Ghani “stole $169m from the state coffers” and called his flight “a betrayal of the state and the nation”. National Reconciliation Ghani’s opportunistic behavior stands in stark contrast to the principled stand taken by Afghanistan’s last left-wing president - Mohammad Najibullah. After assuming power in 1986, he followed a policy of national reconciliation, looking for a political resolution to the proxy war raging in his country. A unilateral ceasefire with the jihadists was proposed and posts were offered to the insurgents in a coalition government. In an attempt to create a broad-based state, mujahedeen leaders, the former king Zahir Shah and ex-ministers from previous governments were invited to join a government of national unity “to rebuild the war-torn country”. Parliamentary elections in April 1988; a non-party candidate, Mohammad Hassan Sharq, was elected prime minister and 62 parliamentary seats were left vacant for the opposition. Addressing the UN General Assembly in June 1988, Najibullah stated that the “flexibility of the present leadership of Afghanistan also includes its decision to give up monopoly on power, the introduction of parliament on the basis of party competition and granting of all political, social and economic rights and privileges to those who are returning.” Significant headway was made in reaching peace accords with local warlords. In 1988, 160 guerrilla commanders had reached agreements and more than 750 were negotiating. An attitude of domestic concord was consistently maintained. On March 2, 1989, Najibullah told Far Eastern Economic Review that all arms shipments to both sides be halted. “If it is said that we get help from the Soviet Union, then let the arms supplies from both superpowers be cut to put an end to the war”. ' Pro-imperialist propagandists had believed that Najibullah would fall within months, if not weeks, of the withdrawal of Soviet troops. However, his government continued to enjoy deep support in many parts of Afghanistan. When the Geneva Accords were being signed, the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) - to which Najibullah belonged - claimed a membership of 250,000. Its organizational branches had a combined membership of 750,000. Afghans preferred government-controlled cities over the mujahedeen-dominated refugee camps in Pakistan, or in Iran. On the military front, the PDPA survived without Soviet intervention. As the last of the Soviet troops were crossing the Amu Darya River, Washington and its faithful auxiliaries withdrew their embassies from Kabul. Shortly, the mujahedeen leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar predicted that “Kabul will fall in weeks, not months, without any major onslaught on the city”. Najibullah defied the hopes of imperialists. Norm Dixon writes: “The contras and Washington expected wholesale defections of the Afghan armed forces to the mujahedeen. It was not to be. As with Jalalabad and Kandahar, two cities which had been being successfully defended solely by Afghan troops for several months without Soviet troops, Kabul too would hold out.” Turning Point The PDPA government’s success in promoting internal stability was suddenly undermined by the 1991 collapse of the USSR. While Soviet military supplies to the Afghan government witnessed an abrupt blockage, American arms and funds continued to flow to the jihadists. Najibullah’s resignation became the sine qua non for any meaningful discussion. Consequently, on March 18, 1992, Najibullah announced he would resign as soon as an authority could be designated to replace him. Emboldened by these developments, General Abdul Rashid Dostum army’s broke its pact of aggression with Kabul to band together with General Ahmad Shah Massoud in early 1992. On April 15 of the same year, non-Pashtun forces that had been allied to the government mutinied and took control of Kabul airport. On April 16, 1992, Najibullah was present at the office of Benon V. Sevan - UN secretary-general’s personal representative in Afghanistan and Pakistan - along with the representatives of Pakistan and Iran. When informed of Pakistan’s offer to grant him political asylum at the Pakistan embassy in Kabul, he clarified: “I said I would submit my resignation in pursuit of the UN peace plan if it would help to end hostilities, and if there would be no assault on Kabul. I warned you that if I announced my intention to resign before an interim government was in place that there would be a power vacuum. This is what is happening today. I fought these developments for three years; I knew what would happen. Once a power vacuum emerges, who will be responsible for law and order and security? Not only the honor and pride of Najibullah are at stake, but also the honor and pride of the UN. I will not go to Pakistan! That is no solution. I prefer to stay at the UN compound. The answer is the UN peace plan, and the Council of Impartials, which will take over as a transitional authority as soon as possible…I offered my resignation today as president of the Republic of Afghanistan, and as leader of the ruling Watan [Homeland] Party [PDPA’s new name, adopted in 1990]. The UN now has the responsibility to make its plan work. I am prepared to sacrifice myself if anyone tries to attack the UN premises, if that will help to bring peace to my country. I am willing to make the ultimate sacrifice.” Referring to Iran and Pakistan - which had been funding different mujahedeen forces - he added, “I don’t trust you, you bastards! I would rather die than be protected by you. And besides, I don’t believe you will protect me.” Thus, for years, Najibullah remained isolated in a UN compound. On September 27, 1996, Taliban soldiers - after winning a bloody civil war with various mujahedeen factions and warlords - captured, tortured, and killed him, then hanged him in Ariana Square, outside the Presidential palace. A writer notes: “Najibullah…was left hanging from a Kabul lamp post with his genitals stuffed in this mouth. By such methods, the “civilised West” and its paid agents achieved their main objectives in...[Afghanistan].” AuthorYanis Iqbal is an independent researcher and freelance writer based in Aligarh, India and can be contacted at yanisiqbal@gmail.com. His articles have been published in the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and several countries of Latin America. Archives August 2021 8/20/2021 Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador wants to revive Simón Bolívar’s dream. By: Andres Manuel LopezRead NowMexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has proposed replacing the Washington-based Organization of American States (OAS) with a more autonomous entity linked to the "history, reality, and identifies" of Latin America and the Caribbean. | Photo released by Government of Mexico The following speech was given by Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador on July 24, 2021, in Mexico City to pay homage to the Liberator Simón Bolívar. AMLO urged the recreation of Bolívar’s project of uniting the peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean, and to rely on history to better face the present and the future. This speech was published on Portside on August 14 and has been slightly edited for length and to match People’s World style. Born in 1783, exactly 30 years after Miguel Hidalgo, Simón Bolívar decided at a very young age to fight for great, noble, and just causes. Like Hidalgo himself and José María Morelos y Pavón, the fathers of our homeland, the liberator Bolívar encompassed exceptional virtues. Bolívar is a living example of how a good humanistic education can overcome the indifference or comfort of those who are born with a silver spoon in their mouths. Bolívar belonged to a well-to-do family of landowners, but from childhood on he was educated by Simon Rodríguez, an educator and social reformer who accompanied him in his education until he reached a high degree of intellectual maturity and awareness. In 1805, when he was only 22 years old, on the Monte Sacro in Rome, Bolívar “swore in the presence of his teacher and namesake not to rest his body or soul until he had succeeded in liberating the Spanish-American world from Spanish tutelage.” Like his father, Bolívar had a military calling, but at the same time he was an enlightened man and as they used to say, a man of the world, for he traveled extensively in Europe; he lived or visited Spain, France, Italy, England; he spoke French, knew mathematics, history and literature, but he was not only a man of thought but also of action. He knew the art of war and was at the same time a political leader with a calling and commitment for transformation. He knew the importance of discourse; the power of ideas, the effectiveness of proclamations and was aware of the great usefulness of journalism and the printing press as an instrument for the struggle. He knew the effect caused by the enactment of laws for the benefit of the people and, above all, he valued the importance of not giving up, of perseverance, and of never losing faith in the victory of the cause for which he was fighting for the good of others. In 1811, Bolívar joined the anti-colonialist army, under the command of Francisco de Miranda, precursor of the Independence Movement. Shortly thereafter, in response to hesitancy on the part of this military leader, Bolívar took command of the troops and in 1813 began the struggle for the liberation of Venezuela. Shortly beforehand, as Manuel Pérez Vila, one of his biographers, writes, the people began to call him The Liberator, “a title solemnly conferred on him, in October 1813, by the municipality and the people of Caracas, and with which he would go down in history.” In his tireless struggle through the highways and byways of the Americas, victories and defeats are intertwined. Bolívar’s military campaign led him to take refuge in Jamaica and Haiti; from these people and their governments he received support for his campaigns on two occasions, something truly exceptional and an example of solidarity and Latin American brotherhood. In 1819, he triumphantly entered Bogotá, and soon after the Fundamental Law of the Republic of Colombia was issued. This great state, Gran Colombia, the creation of The Liberator, included the current republics of Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, and Panama. Not everything was easy in his struggle. He lost battles, faced betrayals, and, as in any transforming or revolutionary movement, internal divisions appeared, which can be even more harmful than the struggles against the real adversaries. In the struggle to liberate the peoples of our Americas, Bolívar had the tremendous support of General Antonio José de Sucre and in 1822, he met, in Guayaquil, Ecuador, with General José de San Martín, another illustrious titan of South American independence. At that time the “Bolívar Republic” was established, today known as Bolivia, and the independence of Peru was consummated. On the coast of this country, at the beginning of 1824, Bolívar fell ill, and despite bad news, due to betrayals and defeats, it is said that from the armchair where he was sitting his famous exclamation “Triumph!” emerged. This anecdote was made into poetry by Carlos Pellicer, who intensely admired Bolívar. The verse reads as follows: Señor don Joaquín Mosquera from a certain town, he arrived. He got off his mule and sought out the Liberator. Old ramrod saddle Leaning on the wall of a miserable house; The sad body of Bolívar rested on it. Don Joaquin embraced him with very courteous words. The hero of the New World barely answered. After Señor Mosquera had enumerated the sorrows, he asked Don Simon: “And now, what are you going to do?” “Triumph!” The Liberator replied with mad faith. And it was a solid silence of admiration and horror…. After that fateful moment, The Liberator lived through many others of equal misfortune. The final leg of his existence was marked by the constant divisions in the liberal ranks, which even led Venezuela to proclaim itself a state independent of Gran Colombia on the eve of his death. On December 17, 1830, the great liberator Simón Bolívar closed his eyes and never woke up. Bolivarismo in history The struggle for the integrity of the peoples of our Americas continues to be a beautiful ideal. It has not been easy to turn that beautiful goal into reality. Its main obstacles have been the conservative movement in nations of the Americas, the divisions in the ranks of the liberal movement, and the predominance of the United States in the hemisphere. Let’s not forget that almost at the same time that our countries were gaining independence from Spain and other European nations, the new metropolis of hegemonic domination was emerging in this hemisphere. During the difficult period of the wars of independence, which generally began around 1810, the rulers of the United States followed events with discreet interest and an entirely pragmatic approach. The United States maneuvered at different times in accordance with a unilateral game plan. Extreme caution at the beginning, so as not to irritate Spain, Great Britain, the Holy Alliance, without hindering decolonization, which at times looked doubtful. However, around 1822, Washington began the rapid recognition of the independence achieved in order to close the door to interventionism from abroad, and in 1823, at last, a defined policy emerged. In October, [former U.S. President Thomas] Jefferson, who inspired the Declaration of Independence and who was by then a sort of oracle, responded by letter to a query on the issue from President James Monroe. In a significant paragraph, Jefferson says: “Our first and fundamental maxim should be, never to entangle ourselves in the broils of Europe; our second, never to allow Europe to meddle in affairs on this side of the Atlantic.” In December, Monroe delivered the famous speech in which the doctrine that bears his name was outlined. The slogan of “America for the Americans” ended up disintegrating the peoples of our continent and destroying what Bolívar had built. Throughout almost the entire 19th century we experienced constant occupations, invasions, annexations and it cost us the loss of half of our territory, with the great blow of 1848. This territorial and violent expansion of the United States was consecrated when Cuba, Spain’s last bastion in the Americas, fell in 1898, with the suspicious sinking of the battleship Maine in Havana. This gave rise to the Platt Amendment and the occupation of Guantánamo. In other words, by then the United States had finished defining its vital physical space throughout the Americas. Since that time, Washington has never ceased carrying out overt or covert operations against the independent countries south of the Río Grande. The influence of U.S. foreign policy is overwhelming in the Americas. There is only one special exception, that of Cuba, the country that for more than half a century has asserted its independence by politically confronting the United States. We may or may not agree with the Cuban Revolution and its government, but to have resisted 62 years without being subjugated, is quite a feat. My words may provoke anger in some or many, but as the song by René Pérez Joglar of Calle 13 goes, “I always say what I think.” Therefore, I believe that, for its struggle in defense of its country’s sovereignty, the people of Cuba deserve the prize of dignity, and this island should be considered the new Numantia for its example of resistance, and I think that for that very reason it should be declared a world heritage site. Exploring another option But I also maintain that now is the time for a new coexistence among all the countries of the Americas, because the model imposed more than two centuries ago is exhausted, has no future, and no way out, and no longer benefits anyone. We must put aside the dilemma of either integrating with the United States or opposing it defensively. It is time to explore another option, that of having a dialogue with U.S. leaders and convincing and persuading them that a new relationship between the countries of the Americas is possible. I believe that at present there are excellent conditions to achieve this goal of respecting each other and going forward together without anyone being left behind. With this in mind, our experience of economic integration with respect for our sovereignty, which we have been carrying out in the conception and implementation of the economic and trade agreement with the United States and Canada, may be helpful. Obviously, it is no minor thing to have a nation like the United States as a neighbor. Our proximity forces us to seek agreements and it would be a serious mistake to physically confront Samson, but at the same time we have powerful reasons to assert our sovereignty and demonstrate with arguments and without idle chatter, that we are not a protectorate, a colony or their backyard. Furthermore, with the passage of time, a factor favorable to our country has gradually been accepted: China’s disproportionate growth has strengthened the opinion in the United States that we should be seen as allies and not as distant neighbors. The integration process has been taking place since 1994, when the first trade agreement was signed, which, although incomplete because it did not address the issue of labor rights, as is the case today, allowed for the installation of auto parts plants and factories in other branches and the creation of production chains that make us mutually indispensable. It can be said that even the U.S. military industry depends on auto parts manufactured in Mexico. I say this not out of pride, but to underscore the interdependence that exists. But speaking of this question, as I said to President Joseph Biden, we prefer an economic integration with sovereignty with the United States and Canada, in order to recover what we have lost in terms of production and trade with China, rather than continuing to weaken ourselves as a region and having a scenario in the Pacific plagued by war clouds. In other words, it is in our interest for the United States to be strong economically and not only militarily. Achieving this balance and not the hegemony of any country is the most responsible and advisable way to maintain peace for the good of future generations and humanity. To start with, we must be realistic and accept, as I stated in my speech at the White House in July of last year, that while China dominates 12.2 percent of the global export and services market, the United States controls only 9.5 percent. This disparity dates back just 30 years since in 1990, China’s share was 1.3 percent and the United States’ was 12.4 percent. Imagine if this trend of the last three decades were to continue, and there is nothing that can legally or legitimately be done to prevent it, in another 30 years, by 2051, China would dominate 64.8 percent of the world market and the United States between 4 and 10 percent; which, I insist, in addition to being an unacceptable disproportionate division on an economic level, would keep alive the temptation to wager on resolving this disparity with the use of force, which would endanger us all. It could be simplistically assumed that it is up to each nation to take on its responsibility, but in the case of such a delicate matter so close to our hearts, with respect for the rights of others and the independence of each country, we think that the best thing to do would be to strengthen ourselves economically and commercially in North America and throughout the hemisphere. Besides, I do not see any other way out; we cannot close our economies or wager on the application of tariffs on exporting countries of the world, and much less should we declare a trade war on anyone. I think the best thing to do is to be efficient, creative, strengthen our regional market, and compete with any country or region in the world. Of course, this involves jointly planning our development; nothing on the order of live and let live. We must jointly define very precise goals; for example, to stop rejecting migrants, mostly young people, when in order to grow we need a labor force that, in reality, is not sufficiently available in the United States or Canada. Why not study the demand for labor and open the migratory flow in an orderly manner? And within the framework of this new joint development plan, we should consider policies on investment, labor, environmental protection, and other issues of mutual interest to our nations. It is obvious that this must involve cooperation for the development and welfare of all the peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean. The policy of the last two centuries, characterized by invasions to put in place or remove governments at the whim of the superpower, is no longer acceptable: Let’s bid farewell to impositions, interference, sanctions, exclusions, and blockades. Let’s instead apply the principles of non-intervention, self-determination of peoples, and peaceful settlement of disputes. Let’s initiate a relationship in our hemisphere based on the premise of George Washington, according to which “nations should not take advantage of the misfortune of other peoples.” I am aware that this is a complex issue that requires a new political and economic outlook. The proposal is no more and no less than to build something similar to the European Union, but in accordance with our history, our reality, and our identities. In this spirit, the replacement of the OAS [Organization of American States] by a truly autonomous organization, not a lackey of anyone, but a mediator at the request and acceptance of the parties in conflict, in matters of human rights and democracy, should not be ruled out. It is a great task for good diplomats and political leaders such as those who, fortunately, exist in all the countries of our hemisphere. What is proposed here may seem utopian. However, it should be considered that without the horizon of ideals we will get nowhere and, consequently, it is worth trying. Let’s keep Bolívar’s dream alive. AuthorAndrés Manuel López Obrador is the President of Mexico. This article was produced by People's World. Archives August 2021 8/20/2021 Remembering Anahita Ratebzad, socialist leader and mother of Afghan women’s liberation. By: Tim WheelerRead NowAnahita Ratebzad, standing at right, speaks with a group of activists. | Ratebzad Family via Twitter All the newspapers and television news programs right now are filled with stories about the dark future hanging over Afghan women and girls as the Taliban retakes control of their country. The Guardian late last week featured an article by an unnamed Afghan woman who said she is now hiding the two university degrees she earned, searching for a burqa to cover every inch of herself as the women-hating fundamentalists of the Taliban close in. She said she taught English language classes. “Every time I remember that my beautiful little girl students should stop their education and stay at their home, my tears fall…. As a woman, I feel like I am the victim of the political war that men started.” For over half the population of Afghanistan, the women, all the gains they have won could now be stripped from them. And for a large majority of men, they too will lose their democratic rights. We should not forget that the U.S. played a treacherous role in determining Afghanistan’s fate, sending in the CIA to arm the counter-revolutionary mujahideen to overthrow the progressive April Revolution back in the 1980s. Among the killers the CIA trained and equipped for these death squads was Osama bin Laden, ringleader in the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. It is also a good time to remember Anahita Ratebzad, the mother of Afghan women’s liberation, and to uphold the gender equality she fought so hard to achieve. When the April Revolution erupted in Afghanistan in 1978, Ratebzad was in the thick of the battle, a leader of the People’s Democratic Party. She wrote a famous polemic that appeared in the May 28, 1978, edition of New Kabul Times: “Privileges which women by right must have are equal education, job security, health services, and free time to rear a healthy generation for building the future of the country…. Educating and enlightening women is now the subject of close government attention.” When the April Revolution triumphed, the new prime minister, Nur Mohammad Turaki, named Ratebzad as Minister of Social Affairs. She was born in the village of Gildara, Kabul Province, on Nov. 1, 1931. Her father supported democratic reforms and was forced by the reactionary monarchist regime into exile in Iran. She saw little of her father as she grew up in poverty, attending a French-language school. She was forced to marry at age 15 to Dr. Keramuddin Kakar, one of the few foreign-educated Afghan men, a surgeon. She and her husband had three children, a daughter and two sons.

But in the years that followed, she was targeted for vicious defamation by Islamic fundamentalists for this bold initiative. Her husband, who supported Afghan monarch Zahir Khan, separated from Ratebzad. They remained separated, although they did not get divorced. Also in 1957, Ratebzad led a delegation of Afghan women to attend the Asian Conference on Women in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the first time ever that Afghan women attended such a conference. By 1964, she had founded the Democratic Organization of Afghan Women, and on March 8, 1965, Ratebzad and other Afghan women organized the first ever march through Kabul in celebration of International Women’s Day. Ratebzad was also a reader, writer, and thinker. In the course of her political work, she became a Marxist-Leninist. She was one of four women elected to Afghanistan’s parliament in 1965 representing Kabul province—the first group of women legislators in the country’s history. Later, during the years of Afghanistan’s socialist revolution, she held several cabinet posts and also served as ambassador to Yugoslavia and Bulgaria at various times. From 1980 to 1985, she was Deputy Chair of the Revolutionary Council—the equivalent of vice president of Afghanistan. No woman before or since has held such a high position in the country.