|

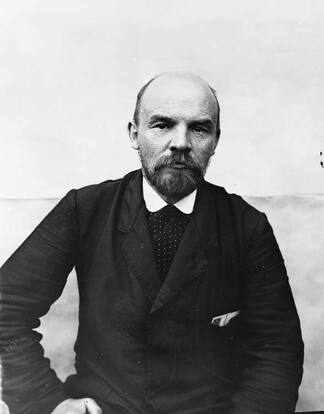

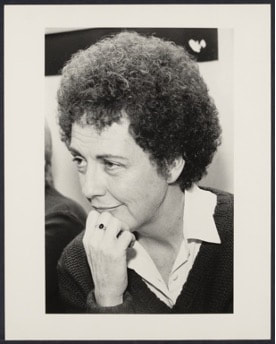

The recent victories of the left in a number of municipalities and in elections for the Constitutional Convention have set the stage for a categorical rejection of the legacy of the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship and the building of a new Chile Daniel Jadue and Javiera Reyes Javiera Reyes, who is 31 years old, is the new mayor of the Santiago municipality of Lo Espejo in Chile. “I grew up in a home where [former President of Chile] Salvador Allende was always the good guy,” she told us, “and [military dictator] Augusto Pinochet was a tyrant. That marked my life.” Reyes’ comment reflects the old divides that have convulsed Chile’s politics since General Augusto Pinochet’s coup d’état against former President Salvador Allende of the Popular Unity coalition on September 11, 1973. Almost 50 years have gone by and yet Chile is still influenced by the legacy of that coup and of the Pinochet dictatorship, which lasted from 1973 to 1990. The May 2021 election that propelled Reyes to the mayor’s office in Lo Espejo also voted in a new Constitutional Convention to rewrite the Pinochet-era Constitution of 1980. Reyes’ victory and the gains made by the left alliance to shape the new Constitution suggest that it is Allende’s legacy that will shape the future and not that of Pinochet. Reyes is a member of the Communist Party of Chile (PCCh), which has rooted itself deeply in Chile’s society over the past 109 years. A PCCh leader--Daniel Jadue—will be the left’s candidate in the presidential election to be held in November 2021. Jadue, like Reyes, is a mayor of a municipality in Chile’s vast capital city of Santiago (a third of Chile’s 18 million people live in Santiago). In the May 2021 election, he was re-elected to the mayoralty of Recoleta, which he has governed since 2012. “There is a historical continuity in [PCCh’s] policy,” Jadue told us, “with the same horizon—updated, of course. No one is thinking of taking up statist projects [again] or socialism as it has been tried, but there is undoubtedly a historical continuity, and we are in one way or another participants in the dream of the people who in the 1970s sought to build a fairer country and who today seek exactly the same thing.” Vote without fearJadue leads in the November 2021 general election polls to replace Chile’s right-wing President Sebastián Piñera. Already, the press has started reporting about the various stances taken by Jadue during his life, particularly his association in the 1980s with Palestinian activism. The smearing of candidates of the left has become part of the electoral process in Latin America: the extreme-right press in Ecuador said that the left-leaning candidate for president, Andrés Arauz, had taken money from the Colombian left-wing guerrilla group ELN (National Liberation Army). The right-wing press also reported that Peru’s current presidential candidate Pedro Castillo, who is leading by a narrow margin, was similar to Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path), which is a guerilla insurgency in Peru. Jadue dismisses these claims made against the leftist candidates. “I want my entire record to be visible because I have nothing to hide,” Jadue said when he spoke to us. The communists participated in the elections held on May 15 and 16 under the slogan Vote Without Fear (Vota Sin Miedo). This slogan comes from a long history, which is part of the party’s legacy. The PCCh was banned, and its members were subjected to persecution over three periods: 1927-1931, 1948-1958, and 1973-1990. Pinochet’s dictatorship killed thousands of communists, including many key leaders. A swath of Chile’s society was gripped by fear brought about by Allende’s socialism, which was essentially a result of the hatred cultivated during Pinochet’s dictatorship. During this time, it takes courage to stand with the communists. Fear of communism has been diminishing, Reyes told us, because the PCCh elected officials have shown their constituents efficiency and compassion through their governance. Jadue’s Recoleta has become a showcase, with a municipal pharmacy, optical shop, bookstore and record store, open university, and real estate project operating free of any profit motive under Jadue’s vision as the mayor of the municipality. Javiera Reyes says that her communism is rooted in her “conception of a municipal government that starts with the universalization of rights and the capacity to create conditions for a good life.” The project of municipal socialism starts with “health, education and common spaces,” says Reyes. It is a project that is “democratic and open to the community.” Unlike Chile’s right-wing mayors, the communist mayors in Santiago such as Reyes, Jadue and Iraci Hassler (who was elected in May 2021 to the mayoralty of Santiago Centro) put the role of women at the core of their policies, including mechanisms to tackle violence against women. They want to create a society without fear in the broadest sense possible. Penguin RevolutionIn 2006, students across Chile protested the privatization of education. Their mass struggle was called the Penguin Revolution because of their black-and-white school uniforms. “The Penguin Revolution in 2006 was my first [introduction] to politics,” Reyes told us. Reyes and Hassler both participated in the massive protests in 2011 and 2013 over the inequalities that marked the secondary and university education in the country. Reyes joined the PCCh during that period. Other students who are currently Chilean politicians, such as Camila Vallejo and Karol Cariola as well as Hassler, were already communists. Student demonstrations came alongside manifestations and strikes by workers from all sectors. Their protests rattled the elite consensus, which since the fall of Pinochet in 1990 had not attempted to write a new Constitution for the country or bothered to formulate a path out of neoliberal suffocation. In October 2019, high school students protested the rise of fares for public transport. This wave of protests, which is ongoing, began to define Chile’s political life. With the slogan “it’s not 30 pesos, it’s 30 years,” the students have highlighted the need for a new Constitution. A new ChileChile has the lowest electoral participation rate in Latin America. After 17 years of dictatorship, trust in the state structures had practically disappeared. Voting was compulsory until 2009, although registration to vote was not compulsory. Young people did not register with the electoral service (Servel). The demand for a new constitution was a wake-up call for the youth. Data shows that more than half of Chile’s young people between 18 and 29 years of age voted in the election, with women constituting 52.9% of the voters. Women and young people will shape the Constitutional Convention, just as women and young women in particular—such as Reyes and Hassler—have taken over the mayors’ offices. The 155-member Constitutional Convention is filled with young people like Reyes and Hassler, a sizable section of the left. The right wing was unable to win one-third of the convention, which would have given it veto power. This means that the new Constitution, which will be drafted in the next nine months, will have a progressive character. On July 18, Jadue faces a primary against Gabriel Boric, another student leader and now a leader of the Frente Amplio (Broad Front). All indications suggest that Jadue will prevail over Boric and then meet the candidates of the right in November. He will be the third communist to run for the presidency, following Elías Lafertte Gaviño (1931 and 1932) and Gladys Marín (1999). If the polls are accurate, Jadue will be the first communist president of Chile. This article was produced by Globetrotter. AuthorVijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is the chief editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest book is Washington Bullets, with an introduction by Evo Morales Ayma. This article was republished from People's Dispatch. Archives June 2021

0 Comments