|

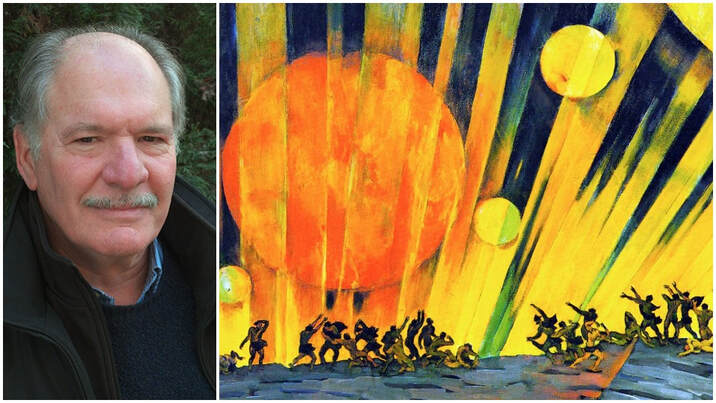

1/22/2022 “Christian Defense Coalition": Pushing Anti-China Lies, Opposing the Olympics in the name of Jesus. By: Caleb T. MaupinRead NowIf one goes to Tiananmen Square in China’s capital city, in the southern part of the square near the tomb of Mao Zedong, the founder of the People’s Republic, you will find The Monument to People’s Heroes. On the base of the tablet you will find the names of 8 historic rebellions against injustice that deeply impacted Chinese society, along with an inscription written by Mao Zedong and Zhou En-Lai that says: Eternal glory to the heroes of the people who laid down their lives in the people's war of liberation and the people's revolution in the past three years! Eternal glory to the heroes of the people who laid down their lives in the people's war of liberation and the people's revolution in the past thirty years! Eternal glory to the heroes of the people who from 1840 laid down their lives in the many struggles against domestic and foreign enemies and for national independence and the freedom and well-being of the people! What few Americans know is that among the heroes upon whom this monument extolls eternal glory are a group of Christians who stood up for the rights of peasants against the horrific brutality of feudalism. In 1851 members of the God Worshipping Society, a Christian organization led by Hong Xiuquan felt they had no choice but to defend themselves. A famine had broken out and the peasants of Guangxi were starving. The God Worshipping Society had built itself by feeding the hungry, caring for those in need, and promoting the message of compassion and kindness found in the New Testament of the Bible. After government troops had been sent to Guangxi to surround Hong Xiuquan’s home, the Christians felt they had no choice but to fight back. A rebellion broke out, and on January 11th, Hong Xiuquan proclaimed that the Qing Dynasty needed to be toppled and replaced by a government that would serve the needs of the people. Amid starvation, government repression and all the horrors of underdevelopment imposed on China by foreign domination, Hong Xiuquan declared the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom as a new revolutionary government to fight for the common people of China against the corrupt gentry and aristocracy. This insurrection lasted 14 years and shook all of China. To those who are familiar with the history of China, it shouldn’t be a big surprise that Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party have erected a monument in honor of a group of Christians. Many of the Americans who visited Mao Zedong’s Eighth Route Army during the 1930s such as Agnes Smedley, Edgar Snow and Anna Louise Strong observed that it seemed very close to early Christianity. The Communists left their old lives and possessions behind, held all things in common, and lived lives of total devotion to serving the people and building a new China. The mystical religious fervor the Chinese Communist Party unleashed among people terrified the US intelligence apparatus in the 1950s and 60s. The term “Brainwashing” entered public discourse, films like “The Manchurian Candidate” and the covert CIA project MKULTRA all flowed from the utter shock and disbelief the US government had at the amazing loyalty and fanaticism that the Chinese Communist Party was able to summon among the population. Even today in China more people attend church each Sunday morning than in the United States. Relations between the Vatican and Beijing have significantly improved in the last few years. The Three Self Patriotic Movement and the China Church Council have existed for decades as religious organizations working hand in hand with the Communist Party. The Chinese government has repudiated and apologized for the persecution of Christians that went on during the Cultural Revolution and huge strides have been made to correct these mistakes, and Christianity is very well alive in China. However, to Americans the idea that the Chinese Communists have a monument to a group of Christians who laid down their lives to fight for justice is very shocking. Because of people like Patrick J. Mahoney and his Christian Defense Coalition, as well as other anti-China extremists speaking in the name of Jesus, the entire reality has been obscured. Now as the Winter Olympics in Beijing are approaching, these forces have reached a shrill volume in their hatred and deceptions. Who is Patrick J. Mahoney?Patrick J. Mahoney is a pretty obscure figure in the United States. He’s got just over 20K twitter followers, and his “Christian Defense Coalition” doesn’t even have a functioning updated website. However, Patrick J. Mahoney has been the lead pastor of something called “Church on the Hill” which is in direct contact with elected officials. “Church on the Hill” describes itself as “a non-denominational Christian ministry and faith-based prayer outreach committed to meeting both the professional and spiritual needs of the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area congressional members (and their staff). As a para-church Corporation, we assist the local church with building spiritual leaders.” As a religious organization receiving 501c3 tax status, “Church on the Hill” is supposed to stay out of politics and function within its mission statement. However, Patrick J. Mahoney is anything but apolitical. If one looks at his social media he seems to have two obsessions, outlawing abortion by overturning the Supreme Court Roe V. Wade decision, and undermining the People’s Republic of China. Mahoney’s participation in anti-abortion demonstrations is something he is very proud of. All across social media he is seen lobbying elected officials, participating in demonstrations and working to undermine something that the US public overwhelmingly supports by a large majority, protecting a woman’s right to make her own reproductive decisions. It would certainly be within Mahoney’s right as religious leader to state his own moral or spiritual objection to abortion, but he goes far beyond that. As a defacto-lobbyist, he is using his position as “Church on the Hill” to engage in activism. Mahoney was arrested during the 2008 Olympics in Beijing and faced serious charges for his efforts to sew unrest in China. He has been banned from returning to the country. However, he is mobilizing his allies to do everything they can to hurt China at a time when it is hosting an international sporting event intended to bring the world together. His followers have been putting pressure on NBC, demanding they not broadcast a very important international sporting event, simply because the host is a government he disapproves of. Where was Patrick J. Mahoney in 2016 when the Olympics were held in Brazil? He was not seen protesting for the rights of the indigenous people of Brazil who have faced brutal persecution. During the Rio games he was not protesting the fact that the US government had just meddled in Brazil’s politics to remove President Dilma Roussef and replace her with a highly unpopular figure named Michel Temer who was an advocate of Neoliberal economics. He did not protest Brazil’s problematic environmental record. When the Olympic Games of 2020 were set to take place in Japan, though postponed due to the pandemic, Mahoney did not protest against the horrific treatment that the peoples of Okinawa have suffered. He did not protest the fact that Japanese leaders have often been caught attempting to whitewash the history of their brutal crimes committed during the Second World War. Mahoney is not really concerned about human rights or social justice, he is simply an anti-China activist. Like Robert Lighthizer and Peter Navarro, he serves a partisan agenda and his activism is tied to individuals with an economic interest in stopping China’s rise. Mahoney repeats widely debunked allegations about Uyghurs, Tibet, and anything else he can drum up. Mahoney is not moved by one particular cause, but simply hatred for one particular country. Chinese officials have admitted that there are indeed human rights concerns and they would like to improve the situation in the country. However, Mahoney is not interested in dialogue with China about how to move ahead on this issue. Instead he seeks to isolate the United States from China and polarize the world economy. Spreading Distrust & Escalating International TensionsPatrick Mahoney should read the Bible he so frequently quotes. In 1 John 3:16-18 the Bible states: “This is how we know what love is: Jesus Christ laid down his life for us. And we ought to lay down our lives for our brothers and sisters. If anyone has material possessions and sees a brother or sister in need but has no pity on them, how can the love of God be in that person? Dear children, let us not love with words or speech but with actions and in truth.” No country in the world has lifted more people out of poverty than China. Over 800 million people have been raised out of poverty in China, and countless millions more have had their lives improved by the infrastructure and development projects of the Belt and Road Initiative. If Mahoney is truly a follower of Jesus, he should be studying the methods China has used to help the downtrodden and hungry people of the world and apply them to the United States. In Matthew 26:52, Christ said to his followers ““Put your sword back into its place. For all who take the sword will perish by the sword.” If Mahoney were truly in line with the Christian teaching he would be urging US officials to stop sending weapons to the pacific and escalating tensions with China. He would be pushing for understanding between the Chinese and American peoples. Opposing international tensions, bringing different peoples and nations together, and learning to love one’s enemies is central to the Christian belief system: “Repay no one evil for evil, but give thought to do what is honorable in the sight of all. If possible, so far as it depends on you, live peaceably with all. Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave it to the wrath of God, for it is written, “Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord.” To the contrary, “if your enemy is hungry, feed him; if he is thirsty, give him something to drink.” (Romans 12:17-21) As Patrick Mahoney lobbies elected officials to be more hostile to China with his “Church on the Hill” and mobilizes to undermine an international event intended to bring the world together, his actions should be roundly condemned. His work is not benefitting the United States or the people of the world. Spreading division and escalating international tensions helps no one, especially in difficult times like these. Author Caleb Maupin is a widely acclaimed speaker, writer, journalist, and political analyst. He has traveled extensively in the Middle East and in Latin America. He was involved with the Occupy Wall Street movement from its early planning stages, and has been involved many struggles for social justice. He is an outspoken advocate of international friendship and cooperation, as well as 21st Century Socialism. He doesn’t shy away from the word “Communism” when explaining his political views, and advocates that the USA move toward some form of “socialism with American characteristics” rooted in the democratic and egalitarian traditions often found in American history. He argues that the present crisis can only be abetted with an “American Rebirth” in which the radicalism and community-centered values of the country are re-established and strengthened. Archives January 2022

0 Comments

1/21/2022 Are Western Wealthy Countries Determined to Starve the People of Afghanistan? By: Vijay PrashadRead NowOn January 11, 2022, the United Nations (UN) Emergency Relief Coordinator Martin Griffiths appealed to the international community to help raise $4.4 billion for Afghanistan in humanitarian aid, calling this effort, “the largest ever appeal for a single country for humanitarian assistance.” This amount is required “in the hope of shoring up collapsing basic services there,” said the UN. If this appeal is not met, Griffiths said, then “next year [2023] we’ll be asking for $10 billion.” The figure of $10 billion is significant. A few days after the Taliban took power in Afghanistan in mid-August 2021, the U.S. government announced the seizure of $9.5 billion in Afghan assets that were being held in the U.S. banking system. Under pressure from the United States government, the International Monetary Fund also denied Afghanistan access to $455 million of its share of special drawing rights, the international reserve asset that the IMF provides to its member countries to supplement their original reserves. These two figures—which constitute Afghanistan’s monetary reserves—amount to around $10 billion, the exact number Griffiths said that the country would need if the United Nations does not immediately get an emergency disbursement for providing humanitarian relief to Afghanistan. A recent analysis by development economist Dr. William Byrd for the United States Institute of Peace, titled, “How to Mitigate Afghanistan’s Economic and Humanitarian Crises,” noted that the economic and humanitarian crises being faced by the country are a direct result of the cutoff of $8 billion in annual aid to Afghanistan and the freezing of $9.5 billion of the country’s “foreign exchange reserves” by the United States. The analysis further noted that the sanctions relief—given by the U.S. Treasury Department and the United Nations Security Council on December 22, 2021—to provide humanitarian assistance to Afghanistan should also be extended to “private business and commercial transactions.” Byrd also mentioned the need to find ways to pay salaries of health workers, teachers and other essential service providers to prevent an economic collapse in Afghanistan and suggested using “a combination of Afghan revenues and aid funding” for this purpose. Meanwhile, the idea of paying salaries directly to the teachers came up in an early December 2021 meeting between the UN’s special envoy for Afghanistan Deborah Lyons and Afghanistan’s Deputy Foreign Minister Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai. None of these proposals, however, seem to have been taken seriously in Washington, D.C. A Humanitarian Crisis In July 2020, before the pandemic hit the country hard, and long before the Taliban returned to power in Kabul, the Ministry of Economy in Afghanistan had said that 90 percent of the people in the country lived below the international poverty line of $2 a day. Meanwhile, since the beginning of its war in Afghanistan in 2001, the United States government has spent $2.313 trillion on its war efforts, according to figures provided by Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University; but despite spending 20 years in the country’s war, the United States government spent only $145 billion on the reconstruction of the country’s institutions, according to its own estimates. In August, before the Taliban defeated the U.S. military forces, the United States government’s Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) published an important report that assessed the money spent by the U.S. on the country’s development. The authors of the report wrote that despite some modest gains, “progress has been elusive and the prospects for sustaining this progress are dubious.” The report pointed to the lack of development of a coherent strategy by the U.S. government, excessive reliance on foreign aid, and pervasive corruption inside the U.S. contracting process as some of the reasons that eventually led to a “troubled reconstruction effort” in Afghanistan. This resulted in an enormous waste of resources for the Afghans, who desperately needed these resources to rebuild their country, which had been destroyed by years of war. On December 1, 2021, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) released a vital report on the devastating situation in Afghanistan. In the last decade of the U.S. occupation, the annual per capita income in Afghanistan fell from $650 in 2012 to around $500 in 2020 and is expected to drop to $350 in 2022 if the population increases at the same pace as it has in the recent past. The country’s gross domestic product will contract by 20 percent in 2022, followed by a 30 percent drop in the following years. The following sentences from the UNDP report are worth quoting in full to understand the extent of humanitarian crisis being faced by the people in the country: “According to recent estimates, only 5 percent of the population has enough to eat, while the number of those facing acute hunger is now estimated to have… reached a record 23 million. Almost 14 million children are likely to face crisis or emergency levels of food insecurity this winter, with 3.5 million children under the age of five expected to suffer from acute malnutrition, and 1 million children risk dying from hunger and low temperatures.” Lifelines This unraveling humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan is the reason for the January 11 appeal to the international community by the UN. On December 18, 2021, the Council of Foreign Ministers of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) held an emergency meeting—called for by Saudi Arabia—on Afghanistan in Islamabad, Pakistan. Outside the meeting room—which merely produced a statement—the various foreign ministers met with Afghanistan’s interim Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi. While in Islamabad, Muttaqi met with the U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan Thomas West. A senior official with the U.S. delegation told Kamran Yousaf of the Express Tribune (Pakistan), “We have worked quietly to enable cash… [to come into] the country in larger and larger denominations.” A foreign minister at the OIC meeting told me that the OIC states are already working quietly to send humanitarian aid to Afghanistan. Four days later, on December 22, the United States introduced a resolution (2615) in the UN Security Council that urged a “humanitarian exception” to the harsh sanctions against Afghanistan. During the meeting, which took place for approximately 40 minutes, nobody raised the matter that the U.S., which proposed the resolution, had decided to freeze the $10 billion that belonged to Afghanistan. Nonetheless, the passage of this resolution was widely celebrated since everyone understands the gravity of Afghanistan’s crisis. Meanwhile, Zhang Jun, China’s permanent representative to the UN, raised problems relating to the far-reaching effects of such sanctions and urged the council to “guide the Taliban to consolidate interim structures, enabling them to maintain security and stability, and to promote reconstruction and recovery.” A senior member of the Afghan central bank (Da Afghanistan Bank) told me that much-needed resources are expected to enter the country as part of humanitarian aid being provided by Afghanistan’s neighbors, particularly from China, Iran and Pakistan (aid from India will come through Iran). Aid has also come in from other neighboring countries, such as Uzbekistan, which sent 3,700 tons of food, fuel and winter clothes, and Turkmenistan, which sent fuel and food. In early January 2022, Muttaqi traveled to Tehran, Iran, to meet with Iran’s Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian and Iran’s Special Representative for Afghanistan Hassan Kazemi Qomi. While Iran has not recognized the Taliban government as the official government of Afghanistan, it has been in close contact with the government “to help the deprived people of Afghanistan to reduce their suffering.” Muttaqi has, meanwhile, emphasized that his government wants to engage the major powers over the future of Afghanistan. On January 10, the day before the UN made its most recent appeal for coming to the aid of Afghanistan, a group of charity groups and NGOs—organized by the Zakat Foundation of America—held an Afghan Peace and Humanitarian Task Force meeting in Washington. The greatest concern is the humanitarian crisis being faced by the people of Afghanistan, notably the imminent question of starvation in the country, with the roads already closed off due to the harsh winter witnessed in the region. In November 2021, Afghanistan’s Deputy Foreign Minister Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai urged the United States to reopen its embassy in Kabul; a few weeks later, he said that the U.S. is responsible for the crisis in Afghanistan, and it “should play an active role” in repairing the damage it has done to the country. This sums up the present mood in Afghanistan: open to relations with the U.S., but only after it allows the Afghan people access to the nation’s own money in order to save Afghan lives. AuthorVijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. He is the chief editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including "The Darker Nations" and "The Poorer Nations." His latest book is "Washington Bullets," with an introduction by Evo Morales Ayma. This article was produced by Globetrotter. Archives January 2022 In a recent article, The New Yorker investigated what it takes for companies to ensure an output of some level of social “good” and not just profits. Beginning with the question “can companies force themselves to do good?,” the answer came from a company called Purpose Foundation: an organization that is attempting to forever change the ownership structure of corporations. The Foundation helps company owners set up what are called perpetual-purpose trusts, which become the “legal” owners of the company itself. What’s more is that these trusts are suffused with social “purposes” whether “sharing profits with workers, protecting the environment, or hiring the formerly incarcerated.” These perpetual-purpose trusts are said to last “indefinitely” and cannot be removed by new owners, thus ensuring a company’s fidelity to certain causes. The reason for creating such trusts is to alter ownership structures entirely, which, according to the Purpose Foundation's co-founder Camille Canon, is “where power is actually held.” According to the article, it's in the “dry, technocratic detail of trust law” where this power can be wielded for good over…what has really only ever been deemed as “less good.” These perpetual-purpose trusts are not without their complexity though. As the article outlines, some decisions are easier to respond to than others: “Some details could be specified precisely; the highest-paid employee, for instance, could never earn more than ten times as much as the lowest-paid employee. But other matters required flexibility and nuance. If the trust mandated that a specific percentage of each year’s profits had to be donated to nonprofits, that might limit the company’s ability to respond to unforeseen events, such as a pandemic or sudden economic downturn.” But the important work is all in finding the right, “socially conscious” investors, as was the case for Matt Kreutz, founder of Oakland-based Firebrand Artisan Breads - a company where Kreutz hires ex-convicts and even offers temporary housing to employees. Consultants from Purpose were able to get him involved with “progressive investors” that were looking to support his business along with the “socially conscious” aspects of his company, as opposed to those who saw this as excess that affected profits. Citing the 2010 Supreme Court Decision (Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission) that granted corporations the same legal protections that people had, Nick Romero makes the observation that if corporations are in fact people, “they’re psychopaths.” And this is where Purpose Foundation’s work lies: in trying to rewrite the “psychology of companies” as it were - “changing the deep structures that shape [corporations’] behavior.” The “imperative to make money” does not need to fall in line with the frenzied, capitalistic behavior of profits for profit’s sake - this “imperative…can be transformed into a requirement to do good.” A “more humane version of capitalism” is on the horizon - so the story goes. Are we saved? Is this the beginning of the end of the old, “evil” capitalism? Are we so bold to wonder “is this a step toward socialism?” Not to forestall hope, but if we are to dream socialist dreams here, the thing that’s obviously missing is any sort of politicization of these perpetual-purpose trusts. People’s World reached out to Purpose to inquire about political alignment or if there were any political projects or action committees at the Foundation. The response was a very plucky “we are doing this work one business at a time” with no political alignments or “legislation writing projects.” This appears to be a purely economic “solution” to the problem of company psychopathology. How are we to compare this to previous attempts at “capitalism with a human face” like co-founder and CEO of Whole Foods John Mackey’s “conscious capitalism” or even “philanthrocapitalism?” Conscious capitalism first began to make waves in the late 2000’s as a way to get companies to focus on “higher purposes” such as employee health and benefits, providing “equitable access” to food all over the globe, and even taking greener measures. It even seems to be garnering strength as capitalism itself has reached the “highest status of anything - above lifestyle, above health, above family, above happiness - and above humanity itself,” leaving some to argue it’s time for this system to “evolve” to take on the “unsustainable” elements of capitalism - i.e. homelessness, growing wealth disparities, and the healthcare crisis. Harvard Business Review even showed companies that practiced “conscious capitalism” performed as well as ten times better than companies that didn’t. The secret to this success? Consumers are making better, more “conscious” choices for where they buy their products and services. Not long before that, philanthrocapitalism was already in the works - an approach to philanthropy that mimics for-profit business structures requiring investors and gauges outputs of “social returns.” Although more commonly associated with Bill Gates and his Gates Foundation as well as Mark Zuckerberg today, such efforts go back to the early days of the Rockefeller Foundation and the Carnegie Corporation. Somewhere within the coordinates of philanthrocapitalism and conscious capitalism we have self-proclaimed “socialist” companies: the best example of this today being No Evil Foods. So, why do we need a more “humane capitalism?” Things seem to be moving in the direction toward progressive, socially-minded companies and consumers are responding well to it. Well, to start, we need to look at the limitations of these “good” companies. To begin with, conscious capitalism is not immune to the laws of value - or, to put it in conscious capitalist terms, the highest of the purposes is profit, or surplus value. Whole Foods was purchased by Amazon back in 2017, and the new parent company has had quite a time during this pandemic when it has come to the conditions its warehouse workers have had to survive through. Terrestrially-bored Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos has doubled his wealth during this same time period. Whole Foods has had some recent turbulence when it has come to knowing precisely which social causes are worth being the most conscious about. Recently, workers had been banned from donning Black Lives Matter slogans on masks and shirts. During November of last year, three Trans employees filed official complaints of transphobia due to harassment - two of which were eventually let go from their respective stores. Whole Foods also removed health benefits for part-time workers and limited hazard pay during the height of the pandemic. Not to mention the paid time-off system where employees can donate PTO to other employees if they are in need of it, rather than the company itself giving out more paid time-off to employees in need or not. Employees are not required to donate, but the moral impetus is clearly put upon co-workers rather than management. Workers rights, Black lives, and trans dignity don’t appear to top the list of “what conscious capitalists care about,” and although John Mackey is quick to point out that Whole Foods was the first to ensure proper sterilizing measures and COVID protocols, he is withholding purposeful action on several other social issues. “I like to keep my political beliefs, beliefs about controversial issues, to myself. I don’t really want to talk about racism. I don’t want to talk about climate change. I don’t want to talk about riots or fires. I want to talk about conscious leadership,” said Mackey during an interview with Isaac Chotiner of The New Yorker. “I’m opposed to racism. That’s my position on racism. End of discussion.” Being purpose-driven with capitalism appears to succumb to the same whims of majority owners, board members, and C-level executives as “regular” capitalism - or, Capitalism Classic. Perhaps philanthrocapitalism is having less of a rocky start to winning over the people. In their recent book Inflamed, Rupa Marya and Raj Patel give a brief historical breakdown of philanthrocapitalism. The Carnegie Corporation, one of the first modern philanthropic organizations to exist, had directly “alter[ed] the course of US medical education and practice,” having helped close five of the seven Black medical schools in the United States at the time; and also was involved in the promotion of “global whiteness,” as political theorist Tiffany Willoughby-Herard put it, for supporting the Afrikaner white nationalism of South Africa. Citing both the Rockefeller Foundation and the Gates Foundation, these “philanthropists” tend to disappear Indigenous knowledge and practices (specifically when it comes to medicine) while purchasing land in which to mine for resources. Gates himself owns 242,000 acres of arable land, some of which he’s using for nuclear power, “making him the largest farmland owner and occupant of stolen territory in the United States.” Pointing out that “[p]hilanthropists traditionally use their money to project their visions onto foreign places,” Marya and Patel conclude that “[p]hilanthrocapitalism is the latest in a long series of technologies for the social reproduction of colonial power.” What about companies that are manufacturing products that are better for the environment and healthier for us? Well, No Evil Foods started their 2021 with union busting and ended with laying off 30 to 50 production workers without severance and canceling their benefits. To no one’s surprise, these efforts were financially motivated and were necessary so that they could, as co-founder Mike Woliansky put it, “save animals and help people be healthier or help save the planet.” These examples of course in no way discredit an entire systematic approach to private ownership of the means of production, even if it is allegedly socially conscious. However, we are left to wonder what is a good company? On the inside, many of us have worked places where we were assured we were a family only to find that this “familial connection” was meant to elicit more time and effort from us, produce guilt for not doing enough or off-loading responsibility onto co-workers, and provide a sense of belonging so employees think how they are treated is “ok.” Asking more of employees has been the method of any and every job or boss, but the “family” functions precisely without having to ask: employees tend to police themselves in this way hoping against hope that if/when layoffs happen, if/when the next pandemic hits, if/when benefits must be cut, they will be spared. This is what conscious capitalism looks like from this side of the looking glass. What about from “outside” a company: what does a “good” company look like from that view? It would appear that this is a much more complex question to answer. After all, does not this view of a company doing good depend fully on the company’s image itself? Where does that leave the actual practices of the business? Any person on the street can celebrate a company like Ford Motor for building a plant dedicated to manufacturing zero-emission pickup trucks while ignoring what this could do to the area’s drinking water and what Ford has a known history of doing in other cities (where many of their employees tend to live) - Flat Rock and Livonia, Michigan both have endured recent toxic chemical spills. In such cases, it would seem we are left to choose between a company’s image and a company’s actions. If a company’s actions are more consequential to our lives, why do we keep coming back to the image? Is this not the precise lesson of Hannah Arendt’s famous concept “the banality of evil?” Rather than simply being “clueless” or unaware of the actions and consequences of a company - who they are exploiting elsewhere, what harm they are causing to the environment, what crimes they are committing - aren’t we fully aware and purposefully ignoring it? Do we not give corporations free passes like this all the time? Chik-fil-A’s recent commercials about how they treat their workers (who we are assured “enjoy” going above and beyond) may make us feel good but has anyone truly forgotten their anti-LGBTQIA+ history? Or is it easier to disavow such histories as simply that: dead and history? Perhaps it's easier to pull into the nearest gas station without considering if one is ready to forgive Shell or BP for their atrocities. It’s here that we must return to the “companies as psychopaths” argument and make a slight change: if companies are psychopaths, us as consumers and employees are sociopaths. But this seems to put a lot of credit into the hands of the consumer/employee. Is ignoring a company’s wrong-doings all our fault or are these companies banking on a “sociopathic” acceptance of their image? First, it’s important to interrogate what the “psychology” of a company means. If a company is a psychopath, then we’re left to conclude that those in the driver’s seat - the CEO, owners, board members - make up the “psychology” we are concerned about here. Second, we need to remember that a company’s “psychology” is all too real today as social media roles proliferate across industries: these being jobs where employees are to act as the “face” and are directly responsible for embodying a company’s so-called values and “speak” its words, as it were. Indulging this psychology both reifies the idea of employee responsibility to ensure a company’s morals and further distances the responsibility of these “psychopathic” tendencies from those actually acting on them. Vegan business magazine, the Vegconomist makes the point even clearer here: “entrepreneurs are just everyday people trying to accomplish big dreams, sometimes unrealistically big dreams. If successful, they create great products, lots of jobs, and consumer and investor value. But it isn’t always a straight line to the top. It is often one step up and two steps back, to then hopefully jump three steps up.” The formula is a little more direct: if companies are psychopaths, it’s because of those who have big dreams of value. Another way to word this is value is both the goal and the driver or in Marx’s formula of capital: money begets product which begets (more) money. Although capital itself has changed - most billionaires tend to have very little actual money in their bank accounts - the goal of (surplus) value through profits has remained. How do perpetual-trusts help us out of this deadlock? Is its fate any different than capitalism in all its flavors? The obvious reaction here is that it’s better to give anything at all to a cause or charity than to give nothing. Indeed, this is true, but what is “humane” and what is “marketable as humane” are becoming indiscernible. Capitalism’s most distinguishing characteristic is its ability to self-revolutionize: what makes it so remarkable is its ability to subsume new forms of relations of production without hitting the limits of those relations. In short, capitalism constantly changes its own conditions of existence and this is where its true power resides. Humanitarian capitalism thus finds its contradiction-to-overcome in the very nature of a perpetual trust: the legal “indefiniteness” of such a trust would be an obstacle to this constant revolutionizing. This leaves these trusts and the companies themselves vulnerable to the threat of economic impact from extensive litigation, either as a way of forcing negotiations or sidelining a competitor. But is this a step toward socialism? No. This seems more like a step to ensure that socialism in fact never comes about. We need only to look at some of Purpose Foundation’s other work to understand the difference between this flavor of capitalism and socialism: the Trust Neighborhood is an effort to ensure clean, safe, and affordable neighborhoods that are also “mixed-income.” This is an interesting euphemism for different classes “coexisting” in the same neighborhood. We’re already aware of the links between class disparities in the same communities and suicide, but this seems to ignore the class aspect as being problematic. This is an effort not to abolish class antagonisms, but, as Slavoj Žižek recently pointed out, to ensure one’s class-identity is respected and remains intact. If we are to take humanitarian capitalism seriously, we must first acknowledge that humanitarian capitalism doesn’t take its own (class) antagonisms seriously enough. The problem with this, above all else, is that it’s a de-politicized attempt at change. The fact that so much of where the “power is actually held” has to do with legalities - from perpetual-trusts, ownership power structures, and Trust Neighborhoods - shows the power the law and state have in economics. To put this more aptly, it is the sphere of economics that is subordinated to the political terrain. Social “good” cannot come from economics alone. Perpetual-purpose trusts or not, the direction of a company’s purpose is determined first by the whims of an owner, executive, or majority shareholder. What’s more is that the legalities of these trusts are subjected to “politics as usual” - a social status quo which we already know all too well. To sum up “humanitarian capitalism,” it seems we’re looking to change everything in order that it all remains the same. AuthorAndrew Wright is an essayist and activist based out of Detroit. He has written and presented on topics such as suicide and mental health, class struggle, gender studies, politics, ideology, and philosophy. Archives January 2022 1/21/2022 Book Review: Marvin Harris- The Rise of Anthropological Theory: A History of Theories of Culture (2001). Reviewed By: Thomas RigginsRead Now This is an indispensable book for all those on the left interested in understanding how the science of cultural (social) anthropology developed over the last three centuries and how it is used to understand (and sometimes control) non-Western societies, especially those that have not developed complex state structures. Harris’ updated edition was published a few months before his death in October 2001.The Rise of Anthropological Theory [TRAT] was first published in 1968 and is still marked by some of the ideological concerns of that era. Harris states that his goal was “to extricate the materialist position from the hegemony of dialectical Marxian orthodoxy with its anti-positivist dogmas while simultaneously exposing the theoretical failure of biological reductionism, eclecticism, historical particularism and various forms of cultural idealism.” What we have here is another shamefaced Marxist inspired work that, due to the political realities of American capitalism, recognizes the validity of Marx’s scientific accomplishments yet halts at drawing the social and political conclusions those accomplishments reveal with respect to the society in which Harris himself lived and worked. Harris called the type of anthropological theory he developed “cultural materialism” in contrast to “historical” or “dialectical” materialism, two forms he thought contaminated by Hegel’s dialectic. Maxinel L. Margolis, in the 2001 introduction to TRAT describes it thusly: “In its simplest terms, cultural materialism rejects the time worn adage that ‘ideas change the world.’ Instead, it holds that over time and in most cases, changes in a society’s material base will lead to functionally compatible changes in its social and political structures along with modifications in its secular and religious ideologies, all of which enhance the continuity and stability of the system as a whole.” This is basically the Marxism of the ‘Preface’ to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy shorn of its revolutionary implications. Gone from this formulation is Marx’s recognition that, “At a certain stage of their development” the productive forces in the material base come into conflict with the relations of production-- those relations turning into their “fetters” which results in “an epoch of social revolution.” The Harris version, tempered by the necessity of academic survival (he was a professor at Columbia) in the 60s, a time when the U.S. government was involved in a world wide anti-Communist crusade [which was actually a crusade against human rights and democratic representation for the world’s poor] stretching from Latin America through Europe, Africa and Asia, has replaced these Marxist revolutionary bugaboos with more acceptable bourgeois formulations: “functionally compatible changes” which “enhance the continuity of the system.” Cultural Materialism will not explain the French Revolution. But it was not designed to. Harris’ revision of Marx is more in line with British Functionalism (different cultural elements function together to promote stability). The main difference being that Harris tries to provide for evolutionary change while the functionalists (Bronisław Malinowski, A. R. Radliffe-Brown) were opposed to ideas of evolutionary (let alone revolutionary) change. Harris’ book is important because it discusses in great detail all the major anthropological theories of culture developed in the West from the Enlightenment to the present. He thinks Marx’s views are vital and he defends them (at least some of them) against all comers, while at the same time giving credit to the discoveries and contributions of other schools of thought. He credits the Boas school (founded at Columbia towards the end of the Nineteenth Century) for its contributions to the scientific fight against racism and racist ideologies, while at the same time rejecting its anti-evolutionary theories of “historical particularism.” His chapter on “Dialectical Materialism” is of particular interest. In this chapter he discusses Marx’s methods of social analysis, including the limitations imposed on it by its Nineteenth Century milieu, and concludes that, “It is Marx’s more general materialist formulation that deserves our closest scrutiny.” What he wants to scrutinize away is the influence of Hegel and, to Harris, the unscientific and outmoded principles of dialectic. [ It is that nasty dialectic that is responsible for contradiction which might not “promote stability”]. After pulling Marx and Engels’ teeth, so they can’t bite the bourgeois hand that feeds him, Harris allows them to become major forerunners of his so-called Cultural Materialism. Harris gives good critiques of both French Structuralism (Levi-Strauss) and British Social Anthropology and concludes with two chapters (22 and 23) which thoroughly explain his own theories. These are the chapters “Cultural Materialism: General Evolution” and “Cultural Evolution: Cultural Ecology.” In these chapters not only are Marx and Engels lauded, but so is Lewis Henry Morgan (Ancient Society, 1877) whose work was the basis of Engels’ The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. Morgan, the founder of American anthropology, was an upstate New York Republican legislator from Buffalo credited by Marx and Engels with independently discovering historical materialism. Harris also discusses Leslie White’s The Evolution of Culture (1943, 1959)--”the modern equivalent of Morgan’s Ancient Society”) [although White may seem a little too mechanical: “Other factors remaining constant, culture evolves as the amount of energy harnessed per capita per year is increased, or as the efficiency of the means of putting the energy to work is increased.”] The important contributions of the Australian Marxist archeologist Vere Gordon Childe (The Dawn of Western Civilization, 1958; What Happened in History, 1946; Man Makes Himself, 1936 and Social Evolution, 1951) are presented as well. All in all, Harris packs into his 806 pages a more or less complete survey of every major school and theory in the history of anthropology. His view, subject to the restrictions and ideological conditions noted earlier, is basically progressive and anyone with a modicum of Marxist theory can easily substitute a more “orthodox”, that is, more consistently Marxist, analysis to replace those areas where Harris’ “Cultural Materialism” fails in its appreciation of the Hegelian-Marxist dialectic. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. Archives January 2022 A classic blunder and smear against an outspoken activist. Anyone who has ever been critical of Israeli actions toward the Palestinian people knows what to expect next—an avalanche of pit-bull attacks and smears that their criticisms of Israel are motivated by racism and anti-Semitism. The latest example is the response to actress Emma Watson’s pro-Palestinian Instagram post, which led (predictably) to Israeli officials and supporters accusing her of anti-Semitism. Among many others, former Israeli UN Representative Danny Danon—in a tone-deaf post--wrote, “10 points from Gryffindor for being an antisemite.” The purpose of such false accusations is of course to deflect attention away from what is happening on the ground—the real (war) crimes that Israel is perpetrating against the Palestinian people—to the supposed motivations of the critics. Unable to defend its criminal actions, all that Israel’s increasingly desperate defenders have left is smear and innuendo, as the attacks on Emma Watson make clear. But the accusations may also have some other unintended consequences—they make real anti-Semitism (the right-wing fascist variety that really does hate Jews as Jews) more respectable and legitimate—and thus even more deadly. In that sense, the Zionist defenders of Israel are among the most dangerous purveyors of contemporary anti-Semitism--the hatred of Jews as a collective. There are two steps to how these unintended consequences are blundered into. First, there is the claim that Israel and Jewishness are the same thing—that Israel is not the state of all its citizens but is the state of the Jewish people alone. The nation-state law, passed in 2018—which gives Jews alone the right of self-determination in Israel, recognizing Hebrew as the sole official national language, and establishing “Jewish settlement as a national value”—makes the link between the Israeli state and Jewishness formal and official. Similarly, the widely adopted International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of anti-Semitism cites one example as “the targeting of the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity” and has a similar thrust—Israel equals Jews. The second step is the increasing visibility of Israeli violence toward Palestinians. Although Israeli propaganda had succeeded for decades in deflecting mainstream attention away from Israel’s crimes, the cloak of invisibility created by its public relations efforts—its hasbara—is disintegrating before the force of reality, its own increasingly cruel and vicious actions, as well as the work of the growing number of pro-Palestinian activists around the world who are using the power of social media to bypass the normal media gatekeepers. While anyone with a passing knowledge of the situation has long known about the brutal matrix of violence and control—from the river to the sea—exerted by Israel over the Palestinian population, that understanding is now increasingly visible and mainstream. (As evidence of this, Emma Watson’s post quickly drew over 1 million likes.) The problem for all of us, not just Israel, is when these two things are put together—the equation of Israel with Jews and the visibility of Israeli atrocities--then Jews as a whole become tarred with the crimes of the Israeli state. As the Israeli journalist Gideon Levy wrote in 2015, “Some of the hatred toward Jews elsewhere in the world—emphatically, only some and not all of it—is fed by the policies of the state of Israel and especially by its continuing occupation and abuse, decade after decade, of the Palestinian people.” In this process, the danger is that actually existing anti-Semitism is being made more respectable as there seems to be some rational basis for it—Israeli atrocities. At a time when the real and dangerous anti-Semitism of the fascist right is on the rise—remember the white supremacist Charlottesville thugs were chanting “Jews will not replace us”—the last thing that is needed is to give it any sheen of respectability, as, albeit unwittingly, do those who insist on the indissoluble link between the brutal violence of the Zionist project and Jewishness. Such a link is of course nonsense. Jews of all political stripes have long been on the front lines of the fight against the racist Zionist enterprise, insisting that it has no part in their own Jewish values based on a belief in universal—not particular—human rights. It is why groups such as Rabbis for Human Rights act as human shields against the attacks on Palestinians by settlers and the Israel Defense Forces. The fight against Israeli policies and Zionist violence is driven by the concerns of social justice and solidarity, not racism toward Jews. Emma Watson is part of an exponentially fast-growing choir of decent like-minded men and women of good faith all over the world, united in their belief that all people, irrespective of their ethnicity or their religion or their nationality, must have inalienable human rights, including the right to life and liberty and self-determination, from every river to every sea everywhere. That includes the long-suffering people of Palestine. The attempted weaponization of anti-Semitism against this movement not only weakens the term as a description of real fascist racism, but in fact serves to legitimate it. If criticizing cruel Israeli policies toward the Palestinians is anti-Semitic, then what is so wrong with anti-Semitism, so this misguided line of thinking goes. As Robert Fisk once noted, “if this continued campaign of abuse against decent people, trying to shut them up by falsely accusing them of anti-Semitism, continues, the word ‘anti-Semitism’ will begin to become respectable. And that is a great danger.” The solution to this is clear: break the erroneous link between Israel and all Jews (between Israel and Judaism) and concentrate on the reality that the Zionist enterprise is an old-fashioned settler-colonial project—driven in large part by the geopolitical interests of its principal sponsor, the United States. Once we eliminate the obfuscation and confusion that result from the lazy (but calculated) accusation of anti-Semitism, the building of an unstoppable international movement of justice for the Palestinians can continue. Let’s get to it! AuthorSut Jhally is professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and founder and executive director of the Media Education Foundation. This article was produced by Globetrotter. Archives January 2022 If ‘the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles’ (Marx, 2004: 137), then Revolutions constitutes a major work of history. Two decades after its original publication, Löwy, along with six other historians, presents a photographic account of all the major revolutions in modern history, from the Paris Commune in 1871 up to the Cuban Revolution of 1959, from suppressed uprisings to liberatory movements across the globe, from the imperial core of Western Europe to the peripheries of China, Russia, and Mexico. Each of these revolutions, given a short overview to preface its photo collection, has been a subject of scrutiny, each has a wealth of historiography attributed to it, but this book takes a different approach, placing the masses – frozen in time – at the centre of how we view such movements. Why this approach? Löwy asserts that photos can ‘capture what no text can communicate’, and, taking it further, states that ‘a photograph allows us to see, concretely, what constitutes the unifying spirit and singularity of a particular revolution.’ (11) What is the significance of photography in revolutions? What can photography do that lengthy histories, academic volumes, and historiographical bookshelves cannot? According to Löwy, photographs of revolutions ‘reveal […] a magical or prophetic quality that renders them permanently contemporary, always subversive. They speak to us about the past, and about a possible future.’ (17) Houzel and Traverso take this further; they assert that viewing these historical events through images, through mere fragments of time, allows us to study the events as they are, without the burden of subsequent historiography. Indeed, they believe that it allows us to ‘strip away a thick layer of retrospective projections, first hagiography and later demonization.’ (109) This is a fascinating point; it is certainly true that these photographs somewhat remove the decades of analysis and revisionism, adulation and defamation, and leave us with the intimacy of agents of history. The harsh colds of winter that characterise the Russian revolution, the solemn recognition of imminent change, and the realisation of those who have driven it, the acceptance of death before the executioner’s gun – facial expressions reveal to us the realities of these movements in ways that transcend nuanced analysis. They isolate movements from future projections, and what is left, for a time, is a measure of historical objectivity. History, however, can never truly be objective. If captions are integral to the meaning of photographs (and the author agrees with Walter Benjamin that they are), if each photo is ‘profoundly subjective because it bears, in one way or the other, its author’s mark’ (13), if text is the ‘fuse guiding the critical spark to the image’ (14) – then that is how we should read Revolutions – not as an objective chronology of images providing an exhaustive, neutral account, but a selection of photographs alongside their own ‘captions’, in this case their accompanying analyses and observations. Therefore, to echo Löwy’s introduction, Revolutions provides both the objective (photographs of reality) and the subjective (analysis of these photos). Formed in chronological order, the way these events are depicted evolves with the development of photographic technology; earlier depiction was far more forced, almost semi-staged, as the time taken to capture an image was extended, and the equipment required bulky and inconvenient. However, much of the way these photos are captured, and indeed the major themes of revolution, remain consistent throughout the last 150 years. One of the first examples of the revolution photographed comes from the barricades of France, 1848, a ‘material symbol of the act of insurrection’ (p.11), and a tactic reemployed throughout future radical movements. The use of barricades coincides with the first evidence of photographed revolution, but 1848 marks the beginning of this account for another reason too; as Löwy asserts, after that year the way ‘revolution’ is understood changed significantly. ‘Revolution’ before 1848 had largely simply suggested a transformation of the state structure, but now denoted ‘an attempt to subvert the whole bourgeois order’ (10). From the barricades of Paris, then, to the brutal repression of the 1905 Russian Revolution, an uprising described as ‘a bolt of lightning that precedes a crash of thunder, which was not long in coming’ (69), where moderate, peaceful demands for civil liberties, land, education and assemblies were met with extreme violence and murder. And the visual representation of this brutality emphasises the scale of violence inevitable in class struggles. It is a theme that occurs throughout history and as such throughout this book; decapitated heads of Chinese rebels, executed workers, and mass graves are explicitly shown, more striking in photography than any academic statistic of death and injury can evoke. The photography of 1905 Russia indicates not only violent repression, but, according to the author, defiance: ‘they don’t appear defeated; on the contrary, their faces display great dignity. This is a sign that the 1905 Revolution, although it was aborted, left an indelible mark on the consciousness of the masses’ (79). Revolutions does not deny the limits of photographical enquiry; how can black and white imagery capture something so colourful as the Mexican Revolution? As Rousset asks, ‘how can one visually do justice’ to intellectual shifts between the Chinese revolutions? (330) And, clearly, photography is restricted by its singular and immortalised focus. Despite this, even in the Mexican Revolution, the contradiction between city and countryside, as ‘urban and rural mexico stood face to face’ (274), is made indisputably clear by photography. The clothes, facial expressions and the unfamiliar, out of place look of rugged, rural Mexicans in the urban centre reveal this phenomenon, one that persists across the world today. Indeed, one of the book’s strongest aspects is its refusal to present the best-known actors and leaders as the centrepiece of revolution – instead, the bulk of photography is dedicated to the real drivers of social change: the masses. As Houzel and Traverso remark, ‘as in all revolutions, the masses – a human sea – are at the center of all events and invade all spaces.’ (114) A striking image of ordinary Cubans at Playa Girón, prepared to give everything to defend their revolution, to defend their sovereignty, is instructive of the popular revolution and represents an unprecedented event: ‘for the first time in the twentieth century, an intervention planned and armed by Washington had been defeated’ (461). Ordinary, unnamed people, women and workers, children and peasants, people forgotten to history are in this volume accentuated as central figures in extraordinary events. This account chronologises the different major revolutionary movements, but it is not simply time that connects them – the photographs of the first Russian Revolution help to explain the conditions and lessons of the successful Revolution just 12 years later. Emiliano Zapata lives on through his eponymous revolutionary descendants decades later, whose own role in history has been guided and shaped by the Mexican Revolution of 1910-1920. The actors of revolution in these photographs are changing the future; they are shaping what will be photographed in later chapters, through the demolition of the old order and in the surreal manner of historical repetition. This is in part explained by Traverso, in his analysis of the failed German revolution of 1918-19: ‘Photography […] revealed that the protagonists know perfectly well that they were living through an extraordinary event, something out of the ordinary, which was breaking up linear time, confounding regular chronology, and marking the eruption of a qualitatively different temporality.’ (212) The photographs in this book constitute memories of won and lost futures – structural ruptures, successful class struggles, as well as repressed uprisings and the killing of revolutions, each movement of which has shaped the next. But they also represent future building, inspiration, and icons who transcend time to play roles in movements long after they have died. It is difficult not to see the similarities within these revolutions, and while barricades evoke the uprisings of the past, no discussion of revolution is complete without its martyrs. Three heroes – Karl Liebknecht, Emiliano Zapata and Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, complex individuals who played major parts in three very different revolutions, become unified through the manner of their downfall, and crucially by the depiction of their deaths through the lens. The photos of their corpses are strikingly similar; upright, vivid, present in their surroundings, alive in all but breath. No image inspires more than that of someone who fell in the midst of attempting the nearly impossible feat of revolution. Revolutions is a major contribution to our understanding of the principal social movements which shape our modern world. It brings us closer to the participants of history, it provides imagery beautiful and haunting, inspiring and brutal. It binds together the unknown agents of history, the ordinary people achieving the extraordinary, and the immortalised heroes of revolutionary movements. The ‘magical or prophetic quality’ attributed by Löwy to this photography is significant here. Iconic revolutionary photography continues to inspire historical movements, and in this sense, Revolutions adds to the existing revolutionary nostalgia. Indeed, if nostalgia is the memory of lost futures (Fisher, 2013:36), much of that which is depicted in this book constitutes the memory of won futures, and the ordinary people who won them. And to again echo Löwy’s introduction, it is in this way that revolutionary photography can both depict the past, and shape a possible future. 13 January 2022 References

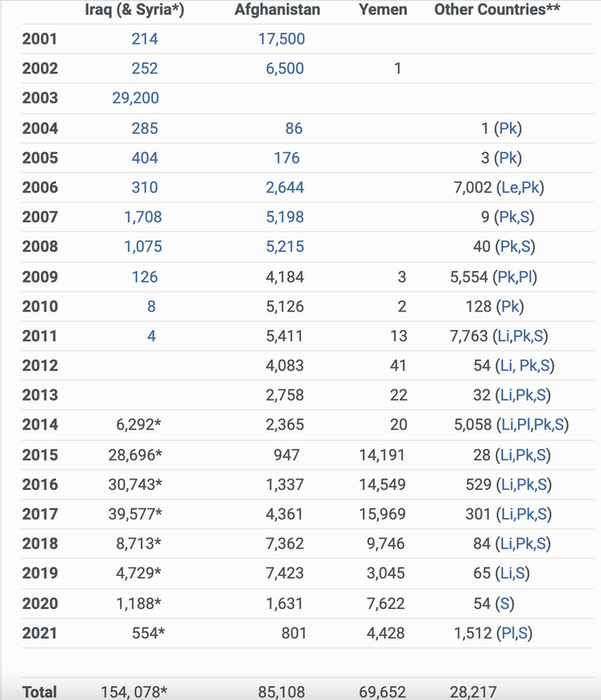

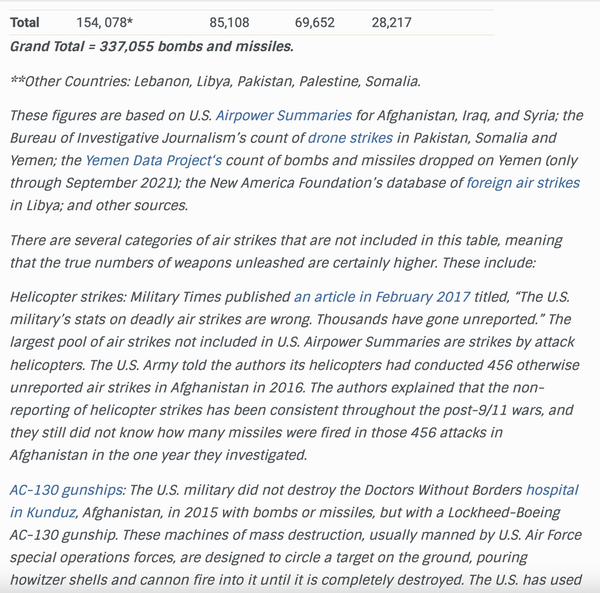

AuthorAidan Ratchford is in the first year of a PhD in Economic and Social History at the University of Glasgow. The article was republised from Marx & Philosophy. Archives January 2022 1/17/2022 Hey, Hey, USA! How Many Bombs Did You Drop Today? By: Medea Benjamin & Nicolas J. S. DaviesRead NowThe Pentagon has finally published its first Airpower Summary since President Biden took office nearly a year ago. These monthly reports have been published since 2007 to document the number of bombs and missiles dropped by U.S.-led air forces in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria since 2004. But President Trump stopped publishing them after February 2020, shrouding continued U.S. bombing in secrecy. Over the past 20 years, as documented in the table below, U.S. and allied air forces have dropped over 337,000 bombs and missiles on other countries. That is an average of 46 strikes per day for 20 years. This endless bombardment has not only been deadly and devastating for its victims but is broadly recognized as seriously undermining international peace and security and diminishing America’s standing in the world. The U.S. government and political establishment have been remarkably successful at keeping the American public in the dark about the horrific consequences of these long-term campaigns of mass destruction, allowing them to maintain the illusion of U.S. militarism as a force for good in the world in their domestic political rhetoric. Now, even in the face of the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan, they are doubling down on their success at selling this counterfactual narrative to the American public to reignite their old Cold War with Russia and China, dramatically and predictably increasing the risk of nuclear war. The new Airpower Summary data reveal that the United States has dropped another 3,246 bombs and missiles on Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria (2,068 under Trump and 1,178 under Biden) since February 2020. The good news is that U.S. bombing of those 3 countries has significantly decreased from the over 12,000 bombs and missiles it dropped on them in 2019. In fact, since the withdrawal of U.S. occupation forces from Afghanistan in August, the U.S. military has officially conducted no air strikes there, and only dropped 13 bombs or missiles on Iraq and Syria – although this does not preclude additional unreported strikes by forces under CIA command or control. Presidents Trump and Biden both deserve credit for recognizing that endless bombing and occupation could not deliver victory in Afghanistan. The speed with which the U.S.-installed government fell to the Taliban once the U.S. withdrawal was under way confirmed how 20 years of hostile military occupation, aerial bombardment and support for corrupt governments ultimately served only to drive the war-weary people of Afghanistan back to Taliban rule. Biden’s callous decision to follow 20 years of colonial occupation and aerial bombardment in Afghanistan with the same kind of brutal economic siege warfare the United States has inflicted on Cuba, Iran, North Korea and Venezuela can only further discredit America in the eyes of the world. There has been no accountability for these 20 years of senseless destruction. Even with the publication of Airpower Summaries, the ugly reality of U.S. bombing wars and the mass casualties they inflict remain largely hidden from the American people. How many of the 3,246 attacks documented in the Airpower Summary since February 2020 were you aware of before reading this article? You probably heard about the drone strike that killed 10 Afghan civilians in Kabul in August 2021. But what about the other 3,245 bombs and missiles? Whom did they kill or maim, and whose homes did they destroy? The December 2021 New York Times exposé of the consequences of U.S. airstrikes, the result of a five-year investigation, was stunning not only for the high civilian casualties and military lies it exposed, but also because it revealed just how little investigative reporting the U.S. media have done on these two decades of war. In America’s industrialized, remote-control air wars, even the U.S. military personnel most directly and intimately involved are shielded from human contact with the people whose lives they are destroying, while for most of the American public, it is as if these hundreds of thousands of deadly explosions never even happened. The lack of public awareness of U.S. airstrikes is not the result of a lack of concern for the mass destruction our government commits in our names. In the rare cases we find out about, like the murderous drone strike in Kabul in August, the public wants to know what happened and strongly supports U.S. accountability for civilian deaths. So public ignorance of 99% of U.S. air strikes and their consequences is not the result of public apathy, but of deliberate decisions by the U.S. military, politicians of both parties and corporate media to keep the public in the dark. The largely unremarked 21-month-long suppression of monthly Airpower Summaries is only the latest example of this. Now that the new Airpower Summary has filled in the previously hidden figures for 2020-21, here is the most complete data available on 20 years of deadly and destructive U.S. and allied air strikes. Numbers of bombs and missiles dropped on other countries by the United States and its allies since 2001: The failure of the U.S. government, politicians and corporate media to honestly inform and educate the American public about the systematic mass destruction wreaked by our country’s armed forces has allowed this carnage to continue largely unremarked and unchecked for 20 years. It has also left us precariously vulnerable to the revival of an anachronistic, Manichean Cold War narrative that risks even greater catastrophe. In this topsy-turvy, “through the looking glass” narrative, the country actually bombing cities to rubble and waging wars that kill millions of people, presents itself as a well-intentioned force for good in the world. Then it paints countries like China, Russia and Iran, which have understandably strengthened their defenses to deter the United States from attacking them, as threats to the American people and to world peace. The high-level talks beginning on January 10th in Geneva between the United States and Russia are a critical opportunity, maybe even a last chance, to rein in the escalation of the current Cold War before this breakdown in East-West relations becomes irreversible or devolves into a military conflict. If we are to emerge from this morass of militarism and avoid the risk of an apocalyptic war with Russia or China, the U.S. public must challenge the counterfactual Cold War narrative that U.S. military and civilian leaders are peddling to justify their ever-increasing investments in nuclear weapons and the U.S. war machine. AuthorMedea Benjamin is cofounder of CODEPINK for Peace, and author of several books, including Inside Iran: The Real History and Politics of the Islamic Republic of Iran. This article was republished from Counter Currents. Archives January 2022

I have followed exactly the same line the whole of my adult life. The fight against fascism and the fight against imperialism were fundamentally the same fight”, Kim Philby was quoted as saying. Philby, alongside some other progressive young people of his generation, understood the deeply reactionary character of capitalism. That is why they began searching for radical ideas, studied Marxism and, some of them, came closer to the communist ideology. In his 1968 book "My Silent War", where he provides a detailed account of his activity as a double agent, Philby writes: "It was the Labour disaster of 1931 which first set me seriously to thinking about possible alternatives to the Labour Party. I began to take a more active part in the proceedings of the Cambridge University Socialist Society, and was its Treasurer in 1952/35. This brought me into contact with streams of Left-Wing opinion critical of the Labour Party, notably with the Communists. Extensive reading and growing appreciation of the classics of European Socialism alternated with vigorous and sometimes heated discussions within the Society. It was a slow and brain-racking process; my transition from a Socialist viewpoint to a Communist one took two years. It was not until my last term at Cambridge, in the summer of 1933, that I threw off my last doubts. I left the University with a degree and with the conviction that my life must be devoted to Communism." In the usually dark world of secret agents, Philby was one of the bright examples who betrayed his own class and served the people of the Soviet Union and the world's proletariat. Below you can read the brief story of Kim Philby published in “Russia Beyond the Headlines” (rbth.com): Harold Adrian Russell Philby (Kim was a nickname) was born into an affluent family: His father, St John Philby, worked in British India, later converted to Islam, and was advisor to King Ibn Sa'ud of Saudi Arabia. Such are the ironies of fate: St John persuaded the Saudis to cooperate with Britain and the USA – instead of the USSR – while his own son ended up working for Moscow for 30 years. Young Philby received a first-class education at Cambridge. While there, he associated with the British Socialists – something he later addressed by saying: "When I was a nineteen-year-old undergraduate trying to form my views on life, I had a good look around and I reached a simple conclusion – the rich had had it too damn good for too long and the poor had had it too damn bad and it was time that it was all changed." The desire to bring equality to the world led him to work for the main citadel of the Left at the time – the Soviet Union. In 1933, Philby was recruited in Vienna by Arnold Deutsch, a deep-cover Soviet intelligence agent. Later, when accused of betrayal, Philby always calmly retorted that he remained true to his own convictions – and that this was more important than loyalty to his country. Arnold Deutsch convinced Philby that, as a secret agent inside British counterintelligence, he would do far more good for the communist cause than any devoted Socialist could, and, beginning in the 1930s, Kim began to conceal his political beliefs: as a correspondent for The Times, he sent reports from Fascist Spain and publicly praised General Franco. Gradually, Philby’s international experience had led to the SIS taking up interest in the journalist, and offering him a job. Philby agreed. After the outbreak of WWII in 1939 Philby became an indispensable agent for Soviet intelligence. Thanks to the decryption of the Enigma code, the British managed to read secret German radiograms throughout the war, and while Winston Churchill was in no hurry to share all the information with his Soviet allies, Kim Philby had been secretly doing that job for him. "You have probably all heard stories that the SIS is an organization of mythical efficiency, a very, very dangerous thing indeed. Well, in a time of war, it honestly was not," Philby told a seminar for East German intelligence officers in 1981. Every day he had left the office with a big briefcase full of the latest papers and reports, and handed them to his contact. The latter photographed them and sent them to Moscow, while Philby put the originals back in their place with no one any the wiser next morning. Philby took personal pride in the 1943 Battle of Kursk: thanks to him, the USSR knew exactly where the Third Reich was planning to deliver the decisive blow – near the village of Prokhorovka – and held back a powerful attack by German tanks, which later made it possible to win the battle. "When Philby was asked what his main achievement in life had been, he would repeatedly say 'Prokhorovka'," Sergei Ivanov, head of the press service of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service, told RIA Novosti.