|

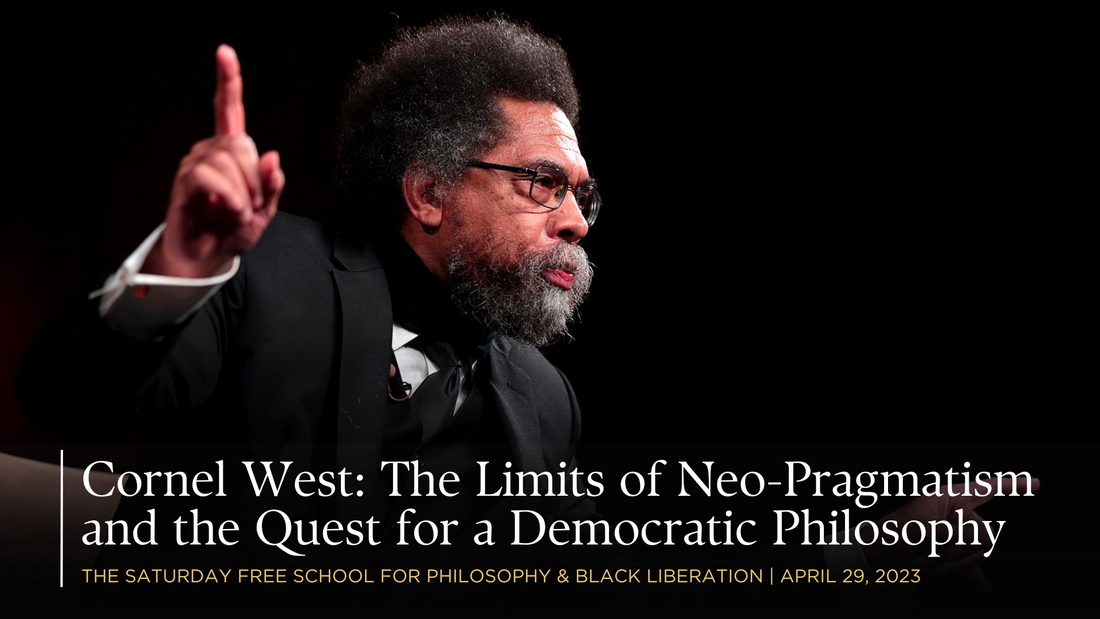

5/17/2023 April 29, 2023 - Cornel West: The Limits of Neo-Pragmatism and the Quest for a Democratic Philosophy By: Anthony Monteiro & Saturday Free SchoolRead NowWe are publishing a transcript of Dr. Anthony Monteiro’s opening remarks from the Saturday Free School’s April 29, 2023 session Continuing Hegel’s Science of Logic. The Free School meets every Saturday at 10:30 AM, and is streamed live on Facebook and YouTube. Good morning to everybody. We are going to go back to Hegel, but it’s always useful to contextualize the reading of a text like this, and to keep the text itself and our reading of it grounded in the reality that we live, including the ideological reality of this time. And so without going for too long, I just wanted to talk about the Cornel West event that we attended at the University of Pennsylvania, and there were a lot of questions that we had afterwards and perhaps we could even you know go through some of those questions again because they are very fascinating and they are philosophical and they do relate to Hegel, the Science of Logic, the whole concept of a philosophical system which I would wish to explain in a moment. And then a little talk about unified theories, and the reason I just wanted to touch on that is because in a certain sense we in the Free School are attempting to forge a unified theory of Lenin and Du Bois, or you know the revolutionary and Marxist tradition of Europe and of the Russian Revolution, and the Black Radical Tradition which is grounded in Du Bois, but I’ll come back to that. Just some things before we read – [I want to] talk a little bit about how we should look at this great work. Frankly, as a not yet complete work, and I think Hegel saw it that way himself – a work in progress. But let’s talk about Cornel West. Last Thursday we attended a really, I think important, lecture by Cornel West. You know, the two most important public intellectuals in the United States today are Noam Chomsky and Cornel West. And there are many, many things philosophically that they hold in common, I think. And there are differences, I also think. As you know, Noam Chomsky is more a social scientist, a cognitive scientist, a theorist of language and grammar and semiotics, et cetera. Cornel West is a philosopher, a pure philosopher. It was a very fascinating lecture. I had not seen Cornel West in a couple of years in person and I’ve only kind of kept up with him in relationship to his political commentary, in effect, as you know, his anti-Trump politics and his claim that Trump is a neo-fascist thug and so on. Which then pushes him of course towards Bernie, and I think that’s a real trap given Bernie’s recent political practice relative to Robert Kennedy’s announcement of his presidency challenging Biden from a very progressive point of view, an anti-war, anti-militarist, anti-corporatist state position. And Biden could not hardly announce his candidacy before Bernie is endorsing him. I mean in good faith you could have waited at least. I mean, how do you just so quickly and easily jump on the Joe Biden bandwagon, and this is the most dangerous presidency in the history of the country threatening war on two continents just because Trump is an alleged fascist, so I got to go with the guy that’s pushing the world toward maybe a nuclear confrontation. Well it doesn’t make any sense, but it does make a lot of sense if you know that Bernie Sanders is a fake socialist, a fake progressive and a political opportunist of the worst type. And I don’t see any other way to put it. We cannot excuse and we cannot apologize for it. Cornel, and this was the sad thing – although Cornel’s lecture stayed at the level of philosophy – and theology by the way – he did say in passing that Biden would be better than Trump without making the argument. I think it was some of that which left most of us, and not quite me – I’m a bit biased for reasons that I’ll try to explain – but most of the people in the Free School who were there found the lecture unfulfilling, I’ll use that language. People can use their own. That Cornel’s brilliance, you know, you get a cat with a huge brain and all of this philosophy and literature and theory packed. A guy who also has, apparently, what is a photographic memory. So he’s a formidable thinker, really a formidable thinker with a big heart. He’s not satisfied with confining himself to his academic office or to a university. He goes into the world, engages with the world, and I should tell you, sometimes putting his own life in jeopardy. There was an instance in about 1998 at the Black Radical Convention in Chicago, and he and I happened to be there and together, and a guy stepped to Cornel in a threatening way. And I happened to step to the guy before he could, you know, accost Cornel. And I never forgot, Cornel was a bit shaken I guess you might say. And he said, you know, “I’m a Christian, but I’m not a pacifist,” you know, blasé blasé blasé. But I’m just saying that to say, I’m certain that for all kinds of reasons, a lot of people feel, because he is accessible, he is in the world, he usually travels alone. Although I kind of sense this time he had a security person with him to help him out, just in the event that somebody stepped to him. But I just say all of that to say that the man has a heart and he has a lot of heart. He’s not a punk. He’s not afraid in that regard. And even in my own case at Temple University, he was so gracious to support me and to even come to a rally that we held, and then to appear at the [Free School’s] Black Radical Tradition conference and speak. And so I’m a little biased because of all of that. Although of course philosophically, we’re not on the same page. And just in his lecture, his determining category is the category “catastrophe.” And his narrative is, how do you live a principled life in the face of social catastrophe? And then along with that, a principled moral life in the face of so many people bending to the politics of the dominant class. And so he is, when he speaks – and he deploys everybody from Chekhov to William James to Kierkegaard – I mean, I’m sitting there and I’m saying, “Oh, I’m hating, man. I’m never gonna be able to know all of that.” And then I’m saying, “I got to put some respect on your name.” I mean just to have achieved that, you know, is quite a bit. And to have achieved all of that knowledge and not used it for his own academic promotional reasons, as y’all know, he left Harvard in the early 2000’s I think because the then-president called Cornel, and this when Cornel was a tenured professor, a full tenured professor in fact, at Harvard. And Lawrence Summers, who was the president – he called Cornel in to his office and tried to, to say intimidate is not really the word – literally to put him in his place, literally saying, “You should be grateful that you have this position at Harvard, and you should thank us, meaning we the white establishment, every day of your life. And therefore we want you to cease this engagement with the hip-hop generation, with the younger generation and withdraw into doing polite and acceptable academic things.” I don’t know what Cornel says but I do know that Cornel can curse. He’s from the hood, you know, Sacramento, so he knows how to curse like I curse. And he may have cursed him out and told him to kiss his behind, and then left Harvard and took a position at Princeton. I don’t know whether Richard Rorty was still around, the philosopher, or who was around but they told him, “Look man, you don’t have to put up with that, come to Princeton.” And then he went to Princeton, and then a few years, maybe ten years later, the black people in particular at Harvard said, “Larry Summers is gone and we want you back here and we will guarantee you tenure, that you will get your tenure back.” So when he went back to Harvard, everybody said, “Oh, yeah, Cornel’s back at Harvard.” You just assumed he had tenure. But he didn’t have tenure. And I put that on the shoulders of the black professors who told him to come back, and did not do what they needed to do to guarantee tenure. Tenure would give him the protection that a person like him needs because he’s going so much against the grain on so many things. Then it turns out, about two years ago, it comes out Cornel doesn’t have tenure. And they’re telling him, “Well, we’ll give you a year-by-year contract and don’t worry about it.” And at that point he left Harvard and took a position at Union Theological Seminary. I think that’s where he began his teaching career and that’s where he is today. But you know, with all of that he maintained his dignity and this is important. When you’re betrayed, and he had to be betrayed in that “come back to Harvard” thing. And humiliation in a certain sense, you know ‘cause a lot of people who for jealousy, envy, just don’t like you ‘cause they just don’t like you kind of thing. “You’re too large, talk too much,” all that, were on the sidelines snickering and laughing. You know how that goes, I won’t go into that. But he handled himself with dignity, he goes back to Union Theological Seminary and hasn’t missed a beat. He continues to be Cornel West and to do what Cornel West does as an intellectual and a public intellectual and a figure that lives with integrity and creates these wide discursive spaces where people like us can both agree and disagree. You see what I’m saying, by keeping the door to discourse, and serious discourse – you know, not just some Afro-centrism kind of, you know, “We are Africans,” and all of that – but drinking from the deep wells of human knowledge wherever he can find it. And of course no one person in his brain can grasp the totality of human civilizations and knowledge, I mean, when I think about string theories and their claim of ten dimensions of space and time, you know I’m often reminded of the Bhagavad Gita, which talk about seven time dimensions. But anyway, I mean, just to wrap your head around the Bhagavad Gita and Plato’s dialogues and Martin Luther, I mean, come on. You need an army of intellectuals who live monastic lives to grasp all of that. But Cornel, unafraid, unashamed, drinks from the wells of knowledge. And of course he could be canceled, just like, you know, “Why are you quoting Plato? He supported a slave-owning society and plus he’s a white man, and a man.” You know, that kind of cancel culture dismissal. Or his thing with Chekhov. But he doesn’t seem to be fazed by it. He continues pushing this high level of discourse, trying to make what is in the end a principled, moral, ethical argument about how to live a life that resists injustice at this time. Now, having said all of that, Cornel West is a combination of what we call neo-pragmatism which is a unique American philosophy; pragmatism arose in the United States as a philosophical movement in the middle of the 1800s. It morphed in the 1960s and 1970s into what we call neo-pragmatism. The fundamental argument of neo-pragmatism – first of all it is American but it’s also English, it’s an English American, we call it Anglo-American philosophical move. As you know, the English philosophers going back in many ways to the beginning, we talk about George Berkeley or David Hume, John Locke – the beginning of English serious philosophy – has always staked out its differences with European rationalism. In particular what they call philosophy that attempts to build systems. In our case Kant and Hegel. Pragmatism, and usually the founder of pragmatism is usually associated with a man named [Charles Sanders] Peirce, whose work I really don’t know, I have to be honest with you. And then further developed by Du Bois’s mentor at Harvard, William James. But what pragmatism argues is that it philosophizes from the standpoint of the ordinary human being, not from the standpoint of a supposed rational system of philosophy and of knowing. Thus it claims to be a democratic philosophy, a philosophy that upholds, I think Cornel has used this word, plebeian democracy, the democracy of the ordinary person. Hence, they often say it is philosophy without foundations, without prior assumptions, without categories. We’ve gone a bit through this, that Kant and Hegel think through categories. For instance the categories of time and space, the category of being, the category of non-being. Each appeals, Kant and Hegel, to logic. Different logics, of course. Hegel, we know, dialectical logic. Kant, more traditional. Each, Kant and Hegel, were trying to align philosophy with science, in particular Newton and Copernicus but Newton in particular. And to align science with philosophy, and this is why Hegel said that philosophy is a science. I think Kant would have agreed with that. Hegel said it is the science of sciences; another way of saying that – it is the scaffolding upon which the meaning of scientific experiments and the meaning of scientific discoveries can be elucidated. This is a huge undertaking by the way, huge undertaking, and remains a part of the way we in the Free School think. We’ll come back to that. But Cornel starts from a pragmatist point of view – that it is the individual seeking meaning in a world that does not in and of itself provide meaning. That is why if you listen to Cornel, there is always on the edge, if you will, or suggesting, that we live on the edge of suicide, of you know, what Jean-Paul Sartre talked, being and nothingness. And how do we realize our being? It is through more moral engagement with a world that will not give us meaning. It is living in good faith, moral good faith in a world where things are commodified, where money trumps principle and hence bad faith. You operate without a moral imperative, without a moral intentionality, you see where I’m coming from. So, neo-pragmatists. Richard Rorty is big in Cornel West’s graduate studies at Princeton. Richard Rorty is the famous academic philosopher, a neo-pragmatist at Princeton. He wrote his last book, a small book but I think a very important and should-be famous book entitled Achieving Our Country. The title of the book he takes from James Baldwin. And Rorty attacks the intelligentsia and the academics who have abandoned the working class. It is a great book, a great manifesto which takes, you know, the whole question of the plebeian or democratic thrust in philosophy, I think, to an important place of engagement. But this is Cornel, you know a plebeian – a people’s philosophy, a people’s framing. Framing philosophical and moral issues from the standpoint of the ordinary person. And that is why I think he has this great fidelity, this great commitment to the blues – with critique, and I didn’t quite agree with his critique. But the blues, which is the narrative of the ordinary people. The blues, talking about navigating the narration of disappointment, but the narration of overcoming, of resilience, of “I’m still here in spite of everything.” He considers the blues to be a very high expression of living morally in a world that tries to undermine your efforts to do that. You know, the pressure is to sell out all the time. But here’s the blues man, the blues woman saying that we can still be principled in spite of the pressure to sell out. So Cornel calls himself a blues man of the mind. He has such interesting formulations. But he sees himself as a blues man and as a traveling musician. He also sees himself in relationship to the blues and John Coltrane. And this scaffolding, this architecture of morality coming out of black resistance is so much a part of him and the way he lives. And you know, even as he talked about music you all might remember, and he really digs Philadelphia, loves Philadelphia because of Philly’s music. And he says Philadelphia’s a soulful city. And he mentioned the O’Jays – and his soundtrack by the way, is the same soundtrack as the Free School. The same music that we listen to, he was gesturing to. The Isley Brothers – did he mention “Harvest For the World”? One of those great calls to morality to resistance. And of course he talked about Stevie Wonder’s love song “Love’s in Need of Love.” You know, which is like us. And the moderator, who I was not too thrilled by. (‘Cause I know some people weren’t there, so I’m filling in, creating a picture.) But the moderator, when Cornel was talking about the O’Jays and the Isley Brothers, [the moderator] tried to say Meek Mills. Now how do you get from that, to that? I don’t see it. But Cornel resisted it, you know in his generous way of course without saying, “I disagree,” but just saying the music that he stands upon. And he’s absolutely right about this, he’s absolutely right. That blues, jazz and R&B is still the strong hand in our music and poetry. But along with neo-pragmatism [for Cornel] is existentialism, a contemporary form of existentialism, and this is again where I would find myself in a bit of a difference with Cornel. For him, the important existentialists would be people like Karl Jaspers and Albert Camus, not Jean-Paul Sartre, the radical, the communist, the socialist, the anti-colonialist. Not Jean-Paul Sartre, but Albert Camus who in fact opposed the Algerian independence movement. Oh by the way this is something that James Baldwin spoke about as well in one of the essays in No Name in the Street, I think the first one entitled “Take Me to the Water.” Jimmy Baldwin did not like Albert Camus either and felt, like Sartre, that Albert Camus was pro-colonialist and operated in bad faith. So it is this sense of the absurd, and in philosophical and existentialist terms, the absurd means non-being or no meaning or lack of meaning. You see what I’m saying. And so it is this tightrope that Cornel navigates upon. To me, it is interesting, it is dramatic, it is exciting. Like I said, “I got to put some respect on your name, hometown. You know, you remain so energized, so hopeful, so alive, you know what I’m saying?” Where it would be easy to say, to throw in the towel, “I’ve been doing this for too long you know. Three of my marriages broke up because of this, I’m going to throw in the towel.” But he stays real, he stays alive and he remains who he is. And welcomes difference and critique. That’s the positive thing. Philosophically, and in terms of social theory, I feel that his approach does not account for a big part of human history including the Russian and Chinese revolutions, the revolutionary leaderships of these movements and their philosophies and theories. It does not account for philosophies paralleling science, or philosophies in the Hegelian or Kantian sense attempting to correct science, and to clarify for scientists and non-scientists what the discoveries of science suggest, in scientific terms and in human terms. That tradition is usually associated with what is called rationalism although it’s much, much more than that. Can you see what I’m saying? Cornel’s position is more in the English American tradition of empiricism, pragmatism and existentialism. There is not … I guess we could put it this way using what we’ve already read in Hegel. There is not, in pragmatism and neo-pragmatism – in fact they reject the whole concept of mediation – it is all resolved at the level of the immediate, and of the individual. And not to mention, that English philosophers – I would say everybody from John Stuart Mill through Bertrand Russell and up to till present, have always smeared Hegel as somehow being the source of authoritarianism and even Nazism. That the rationalist tradition, especially as it crystallizes in Hegel’s philosophy, can only lead to anti-democratic practices and that to return democracy to philosophy, you have to separate philosophy from what is called the rational tradition, or thinking through categories. We can come back to that. So it is a claim and I think this is a problem for Cornel because it generalizes, in fact reduces the question of democracy to an Anglo-Saxon practice. That everything that is not Anglo-Saxon in its theory and practice of democracy is by definition authoritarianism. Well does that sound familiar? Yes it does, because that’s the paradox that the Biden administration and the US ruling class tries to present us with. Either Anglo-Saxon democracy or authoritarianism. Either John Locke and John Stuart Mill – or Hitler. I won’t say my friend, but a guy that I follow, Lex Fridman is always doing, sadly, this conjunction of Mao, Stalin and Hitler – they’re all the same, you know. But that’s the Anglo-Saxon smearing of human revolutionary aspirations. So when you listen to Cornel, he is operating and thinking within the folds of Anglo-American philosophy, and hence the unusual in the political arena that does not fit the narrative of Anglo-American democratic theorizing and narrative is thereby authoritarian and even neo-fascist. And I want to underline the unusual, because the thing of Anglo-American philosophy has become a dogma rather than a project of scientific critique, of democracy and the possibilities of changing it, of advancing it. I just want to say a couple of few other things. In this sense, and people who were there, we saw a crescendo in his narrative, and to me it was exciting because I’m trying to, you know – all of these people, you know, I read, I know a little bit about. But he seemed to weave this narrative out of all of these thinkers from Chekhov to Kierkegaard to William James, and just, I mean just unbelievable, man. That’s why I said, “I got to put some respect on your name.” But in the end, he reaches the apogee and he couldn’t go any further. And then it had to be a repeat. It had to be a re-do, re-saying of similar things that he had previously said because he refused to go to the world of contradiction, of possibility, of danger. He stayed within this beautiful narrative, this exciting narrative that he started with. The other thing is his constant referencing and gesturing to Christianity, in the sense of liberation Christianity or Black Christianity. No problem. As we all know through our own experiences and observations, that Black religion is a religion of resistance, that being is realized in-becoming as Martin Luther King said in one of his graduate school papers. Being is in-becoming. That for Black Christianity, the end is not an end, it is the beginning of something new. And he’s right about that. But then, to me there’s a paradox between Anglo-American political theory and philosophy, and Black Christianity, which is not grounded in the individual or not grounded as Cornel West suggested, in fake hope in the future. It is futuristic but not this Disneyland futurism of the standard ruling class narrative in this country. And just my last point, I think he gets King wrong. King was not a naive pacifist. If you want any evidence of that just listen to the speech “Why I Oppose the War in Vietnam.” King understood St. Thomas Aquinas’s differentiation between just and unjust wars. I don’t think that Cornel understands the actual and practical real-life meaning of that as it relates in particular to the Ukraine War. Is Russia an imperialist nation, as he says? Or is Russia defending itself against the imperialism, militarism and aggression of the United States. Were the Vietnamese waging a just war? Were Koreans waging a just war? Were they waging a war for peace? King understood that. He understood the difference between just and unjust wars. And I think that rather than pigeonholing King into this nebulous, ill-defined category of pacifism – you know, King was far too philosophically developed to be reduced to that. What Cornel has not considered is that King in fact was a theorist and practitioner of the struggle for democracy. A peaceful means, a political rather than a civil war path to the democratic and political transformation of the American nation; to disarm the ruling elite in its efforts to pit black against white in the struggle to change the country, for black and white people. That is what King was saying. He was a theorist and a practitioner of the struggle for democracy. The concept of love. You cannot, in King’s sense, appeal to pragmatist or neo-pragmatist philosophers, or to English theorists of liberal theory or society, to understand King’s concept of love and the Beloved Community. It seems that Cornel missed a tremendous opportunity to further develop, to further deepen, to further extend his own theory of moral behavior and moral action. How beautiful might it have been if he could have turned or extended that discourse to King’s notion of the Beloved Community, which goes hand-in-hand with his idea of the means to radical transformation as important – this is King – as important as the ends themselves. So King was talking about a democratic path to achieve a new democracy, that unites and transforms the people in the process. I don’t think the philosophies that ground Cornel necessarily predisposed him to that kind of Kingian or even Baldwinian thinking. I’ll stop there and just say that we had a rich discussion for the time that it lasted on Thursday evening. AuthorDr. Anthony Montiero is a long-time activist in the struggle for socialism and black liberation, scholar, and expert in the work of WEB Dubois. In fact, he is one of the most cited Dubois scholars in the entire world. He’s worked and taught longer than most of us have been alive. Currently, he organizes with the Saturday Free School for Philosophy and Black Liberation in Philadelphia. This article was republished from Positive Peace Blog. Archives May 2023

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed