|

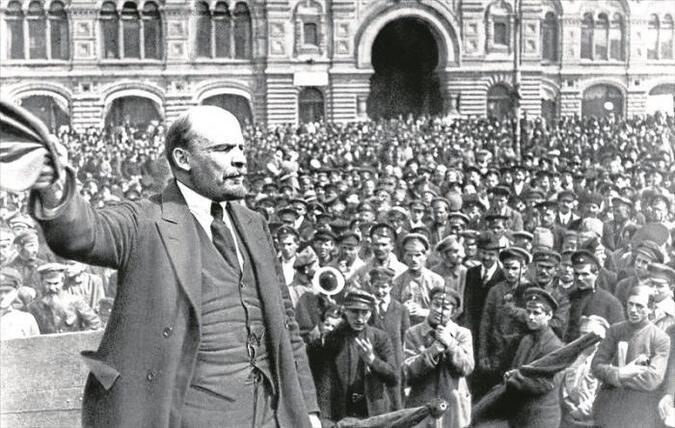

4/28/2022 About the Leninist theory of imperialism. By: Néstor Kohan -Translated By: Valeria BacaRead NowLenin. Indomitable. Indigestible. Hard nut to crack. The mere mention of his name makes businessmen, bankers, policemen, soldiers, intelligence agents tremble. Capitalism as a worldwide system Lenin. Indomitable. Indigestible. Hard nut to crack. The mere mention of his name makes businessmen, bankers, policemen, soldiers, intelligence agents tremble. Unlike other members of the Marxist family (which encompasses in its plurality fathers, mothers, brothers, uncles, cousins, grandparents, etc., with an immense kinship in common and, sometimes, with quarrels and internal disputes, as happens in every family), Lenin constitutes the element of discord. He is the true watershed in contemporary social sciences and politics. The culture of the ruling classes, trained in the daily exercise of exerting their hegemony, tried to sweeten, neutralize, and even engulf or incorporate Walter Benjamin, Antonio Gramsci, Rosa Luxemburg, reaching to the limit of manipulating the very founding grandfather of the family, Karl Marx. With Lenin they never could. He continues to generate panic, despair, and horror. Not only is his thought impenetrable to the bourgeoisie and imperialism on a world scale, but Lenin became the main antidote against any Eurocentric temptation, a senile disease of Marxist theory. From his actions, socialism, communism, and the revolution ceased to be the property of the white and civilized population. Ho Chi Minh's words still resonate when he recalled his tears of emotion upon reading Lenin for the first time and discovering that with the thought of the Bolshevik leader, communism was beginning to truly become universal, ceasing to be an article of European, white, urban, modern, and exclusively western consumption. With Lenin, communism became for the yellow, the indigenous, the black, the subaltern classes and the subjected peoples of the Third World. Therefore, Lenin represents the indissoluble link between Marx's Capital (the theory of power, domination, and exploitation at its highest level of theoretical abstraction) and the specificity of the economic and social formations of Our America. His theory of capitalism as a worldwide system, today globalized to unimaginable levels, is condensed in his work Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916), a work that is more than a century old. In many of his theses it is possible to find articulating links between the theory of the general and structural crisis of capitalism, the hefty agenda of the international revolution, and the specific problems of Latin American dependency and the Third World revolution. There is only one Lenin?The answer to the question at the head of this section is obviously negative. As a working hypothesis it is assumed that there are many Lenins. Not only because his work changed in the heat and rhythm of the class struggle, but also because subsequent appropriations prioritized one aspect of his work over another, depending on the political angle of his interlocutors or followers. It is not the same Lenin, the young man who began to study Capital at the age of 18 (1), the one who fought in 1894 against late Russian populism and postulated Marx as the objectivist founder of sociology and the social sciences (still without having studied Hegel). To the one who at the beginning of the 20th century became a theoretician of the revolutionary organization with his unforgettable What is to be Done? (text in which the media are fundamental for the Bolshevik thinker); the one who reflects on the insurrection of 1905; the theoretician of abstentionism, clandestine organization and guerrilla warfare; the one that argues during 1908 with liquidationist fractions in exile, seduced by the neopositivism of Mach and Avenarius; the one that breaks up with his teachers Plekhanov and Kautsky (both in theory and in practice) while compiling and reconstructing Marx's incendiary correspondence with Kugelmann. The one who argues with his admired comrade Rosa Luxemburg. The one who during the First World War studied Hegel's Science of Logic in the Zurich libraries (revising his own previous books). The one who at that time reads and annotates Clausewitz’s On War, Hilferding's Financial Capital, Hobson's Study of Imperialism and, meanwhile, builds his own theory of imperialism that would come to light in 1916. The one that systematizes the Marxist theory of the State from his analysis of the work of Marx and Engels, in the heat of the Paris Commune. The one who returns in the famous armored train and poses the ground-breaking and iconoclastic April Theses in 1917 (which unsettles the entire Bolshevik Central Committee). The one who prepares the insurrection of October of the same year; the one that commands the civil war and defeats various invading armies with war communism; the founder of the Communist International. The one that has no choice but to go back economically with the New Economic Policy (NEP) and change the international strategy by adopting the united front. The one who deeply ill -no longer able to write with his own hands- leaves a testament where he warns about the enormous difficulties to the other members of the central committee to lead the Bolshevik party and the Soviet state (Lenin, 1974b; 1987). Was he always the same Lenin? Yes and no. He was invariably the same indomitable, radical, unyielding revolutionary. From a very young age, until his death in January 1924, he had the same aspirations that he would never abandon: to change the world, demolish capitalist institutions and emancipate, through revolution and socialism, all the oppressed and exploited people in history. But his work was changing, it was becoming richer and more complex, with emphasis on one or another aspect of reality and theory according to the concrete analysis of the concrete situation and according to the various levels of the relationship of forces in the confrontation of the social classes, both internationally and nationally. For this reason, reducing Lenin to a single book, to a single sentence, betrays or, at least deforms and petrifies, the spirit of his permanently boiling thought.(2) Foto: Periódico La Vanguardia Where to read Lenin? If it is accepted, at least as a hypothesis, that there is not a single Lenin -canonized a posteriori at the taste and pleasure of the good consumer, according to the conveniences and opportunities of the moment-, from where to read this great teacher of revolutionaries? Everyone will do it from their own interests and political positions. And it is not wrong, it is inevitable. This article proposes only one angle among many: the study and, therefore, the vindication of its scandalous validity. Lenin assumes for this analysis the look that several readers of his work have had on him. Here we mention just a few. In each of the referenced books a different Lenin is offered:

His theory about imperialism, a century laterAlthough this short essay intends to reminisce about Lenin and invite others to study him, it cannot ignore various challenges, demonizations and supposed overcomings that circulate, mainly at the academic level, but also, in some segments of the left, who follow trends that circulate in the market of ideas according to the latest craze, without asking who starts it?(3) Of all the literary mass that focuses its cannons against Lenin, the name of Ernesto Laclau deserves to be mentioned locally (who belonged to the so-called national left, first, then in Europe turned postmodern, and finally, during the last decade, Kirchnerist). With less prestige and repercussion than this former follower of Abelardo Ramos (recycled as a neogramscian, supporter of the last Wittgenstein and Derrida) but with the same rancor against Lenin, is the collective volume compiled by Werner Bonefeld and Sergio Tischler, of a clear autonomist invoice, with neozapatist pretensions (Bonefeld y Tischler, 2002). In the specific case of the challenge against the Leninist theory of imperialism, J. Warren and John Weeks can be cited, summarized in the voice "Imperialism and world market" of the famous Bottomore dictionary (1984).(4) Leaving aside all that anti-Leninist arsenal, which enjoys the applause of the media, the "disinterested" financing of NGOs and other "philanthropic" foundations and academic celebration, it is necessary to return to the underlying hypothesis of this article. Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, constitutes in Lenin's thought a point of arrival, both theoretically and politically.(5) In terms of theoretical research, Lenin spent a long time in exile at the Zurich Library (in Switzerland) in order to understand, first, the transformations of capitalism that resulted from the First World War and, secondly, the intimate reasons that made it impossible for the Socialist International (where he was a member, alongside Rosa Luxemburg, and others) to understand the nature of the imperialist war and adopt a dignified and internationalist position before it. In said library, as early as 1915, Lenin wrote 15 notebooks from which he extracted 148 books, (106 in German, 23 in French, 17 in English, and 2 translated to Russian); 232 articles of 49 periodic publications (206 of those in German, 3 in French, and 13 in English) (Aguilar, 1983, p.86). These works, polished and transited in Lenin’s mental laboratory, speak of the seriousness with which he worked and researched (so distant from the postmodern frivolousness and empty and superficial rhetoric of the contemporary poststructuralism) (Lenin, 1984). Within this material, at least, four works should be highlighted: three books (John A. Hobson: Imperialism: A Study from 1902, Rudolf Hilferding: Finance Capital -1909, translated to Russian in Moscow in 1912-; Rosa Luxemburg: The Accumulation of Capital -1912-) and Nikolai Bukharin’s article, prefaced by Lenin: Imperialism and World Economy (1915). To these texts Lenin adds the use of many others, such as the writings and analysis of Heymann, Herman Levy, Vogelstein, Riesser, Kestner, Liefmann, Tafel, Lansburght, Kaufmann, Schulze-Gaevernitz, Stillich, Sombart and Lysis (from who he adopts the expression financial oligarchy), among many others. But Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism goes far beyond those primary sources, filled with statistics and empirical analysis on the centralization and accumulation of capital. In said work, Lenin fuses various paradigms into the same theory, overflowing, by far, the economic literature consulted in the Zurich library. His text, which has a simple prose since it was written for militant purposes, contains substantive theses that still deserve to be discussed today (demonstrating, once again, that the depth and sharpness of thought do not necessarily have to be accompanied by a baroque prose, cryptic, and inaccessible to ordinary mortals). The Leninist theory of capitalism, understood not as a mechanical sum of national social formations, unconnected and juxtaposed, but rather as a global system, polarizing and hierarchical of domination between societies and nations, creates a general picture of the world capitalist economy; unit of analysis that corresponds to the most concrete dialectical category according to the various research plans of Karl Marx in his Grundrisse (1857-1858), with the plasmation of a theory of world war, violent continuation of politics under other means of exertion of material force that he evidently adopts from Clausewitz (Lenin, Ancona, et al., 1979, pp. 49-98).(6) Foto: Getty Images Imperialism, war, and dialectics "World capitalist system" and "world war" are notions that can only be understood from the Leninist theory of “uneven and spasmodic development” (Lenin, 1960, p. 458),7 because the contradictions, hierarchies, and dominations of those are produced between imperialist, dependent, semi-colonial and colonial countries. These qualitative leaps in history (from free competition to monopoly, from the hegemony of industrial capital to the merger and assembly of industrial and banking capital under the absolute aegis of finance capital, of "peace" as a stable international rule between nations to the open war for the distribution of markets and natural resources, from anarchy to planning, from the trade union to the industrial branch union, etc.), can only be understood from a logic in which identity is transformed in difference, one in opposition and another in antagonism. This gave life to contradiction as the main engine for the movement of the whole system. It was not the classical logic of Aristotle nor the mathematical logic of the Vienna circle (then in vogue) that allowed us to understand such global capitalist confrontation. For not understanding these qualitative leaps, the old social democracy remained a prisoner of its mentality, typical of times of relative stability of nineteenth-century capitalism, unable to understand the outbreak of the acute crisis, the emergence of war and the appearance of revolutionary situations that opened the door to revolutionary civil war. In order to understand these qualitative leaps in the capitalist world system that branded the turn of the century, Lenin chose to study in depth Hegel's Science of Logic, which Marx had used in the writing of Capital, as a key substrate to deploy the notion of the contradictory identity of merchandise that already, in its simplest social form, contained the possibility of the capitalist crisis and the outbreak of war in the confrontation between classes and between oppressor and oppressed nations. Not coincidentally, in the epilogue of 1873 to the second German edition of Capital, it was Marx who made this use of dialectical logic explicit in his great work, coming to declare himself, without any ambiguity, as a disciple of Hegel, when at that time in all official philosophy of Germany (in a way analogous to what happens today under postmodern and poststructuralist influence) Hegel was declared a “dead dog.” In the midst of the monstrous accumulation and centralization of financial capital and the First World War, Lenin read those 148 books and 232 articles on political economy, while studying and commenting on Hegel's Science of Logic. The results were his now famous Philosophical Notebooks (Lenin, 1974a).1 The conclusion reached by Lenin in this analysis was the following: “It is impossible completely to understand Marx's Capital, and especially its first chapter, without having thoroughly studied and understood the whole of Hegel's Logic. Consequently, half a century later none of the Marxists understood Marx!” (Lenin, 1974a, p. 168).2 Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, condenses all the economic literature of the moment (from the socialist and Marxist to the bourgeois statistics of the ideologues of the capitalist banks), combining them with Clausewitz's theory of war and Hegel's dialectical logic. Constellation, already rich and extremely complex in itself, to which Lenin adds an acute reading of Marx's writings on the Irish National Question, which led him to publish his famous thesis: “The Socialist Revolution and the Rights of Nations to Self-Determination” (1916) -in which the phrase of the indigenous Peruvian Dionisio Yupanqui reappears, delivered in the Cortes of Cádiz at the beginning of the 19th century, read and assumed as his own by Marx when he was studying the Spanish revolution: “no nation can be free if it oppresses other nations.” The Leninist theory of imperialism has as its necessary and inescapable correlate the vindication of anti-imperialist wars of national liberation and the right of the oppressed nations to self-determination. In this way a mental opening begins in world Marxism towards the peripheral world, colonial and dependent, lightening, at last, the civilized shoulders of "the heavy burden of the white man" and his "duty to bring civilization" to the subjugated peoples from the Third World. From then on, Marxism became truly universal and the battlefield against the domination of capitalism encompasses the entire world, not just France, Germany, England, and the United States. The central theses on imperialismObsessive scholar, rigorous thinker and radical revolutionary, Lenin wrote for the popular militancy. That is why he used to synthesize and summarize his conclusions in such a way that they were understandable to the majority. In this way, he summarizes in five conclusions -even enumerating them, because his popular pedagogy reached that far- the corollary of his extensive, detailed, and acute studies on the theory of imperialism. According to his own pen, his five central traits were as follows:

To these central theses, Lenin added many others of lesser explanatory rank but no less political importance, such as the co-optation of the labor aristocracy in the imperialist countries, fractions of the working class that are inoculated with political opportunism and the lack of internationalism in exchange of colonial crumbs and insignificant fractions of surplus value extracted from the Third World. Lenin detailed a long series of explanatory sequences associated with those central theses. For example, he wonders where the world economy and imperialism emerge from. His response, based on overwhelming empirical evidence and on chapters 22 and 23 of Karl Marx's Capital, maintains that this transformation of the capitalist system is a product of the tendency to accumulate, concentrate and centralize capital, from which trusts, cartels, and monopolies are generated under the predominance and hegemony of financial capital. Monopolies are defined as the merger or assembly of banks, industries, and States; therefore, they are not only or exclusively economic entities, but also include elements of a political and even political-military order. The export of capital (not only of merchandise, although it contributes to the extortion of dependent countries so that they buy merchandise from the imperialist countries) is carried out and is poured into socialized and regulated industrial branches according to a plan. Although the world capitalist system continues to be governed by the rationality of the part that prevails over the irrationality of the whole, there are specific branches and sectors of what is now called the value chain where planning goes hand in hand with generalized anarchy and profligacy of global social work. Within this imperialist horizon, the reign of multinational monopolies perpetuates the conquest of raw materials and natural resources, mainly in the dependent periphery. From a political point of view, this presupposes the corruption of the labor aristocracy and opportunism as a legitimizing ideology within the exploited classes in the imperial metropolises. How else can the enthusiastic support of large segments of the European and US working class for the genocidal bombings of defenseless populations in the Third World, still today in the 21st century be understood? The appropriation and prolongation of Lenin by Ruy Mauro Marini and the Marxist theory of dependency An old and ancient medieval debate between realists and nominalists left among its main conclusions that suppressing a word from the language does not eliminate the reality that this term designates. Therefore, canceling the notion of dependency or proscribing the expression imperialism in the field of social sciences in no way annuls the processes that these expressions -central in the social sciences and, in particular, in the Leninist theory of the world system- pretend to explain. The cruel capitalist reality of our days refuses to be happily swallowed by the linguistic turn. Having already spent more than forty years since Eurocommunism, social democracy, and their various ideological modulations, mainly associated with post-1968 metaphysics, were weaving together to tame, sweeten and make critical social theory lighter, perhaps the time has come to recover the most radical currents of Latin American social theory. The one that tried to appropriate Lenin to critically study and discuss the character and conflicts of the social formations of Latin American capitalism. Among them the work of the revolutionary militant of Brazilian origin Ruy Mauro Marini (1932-1997) stands out. Several decades after Lenin (who died in 1924), Marini once again recovered in politics and in the social sciences the internationalist perspective fostered by the Bolshevik thinker. He did so long before the term globalization became fashionable, and even, reached the zenith of his fame and prestige with Wallerstein's modern world systems theory. The general context in which Marini elaborated the foundations of his Marxist reading of capitalism is marked by the rise of anti-imperialist and anti-colonial revolutions in the Third World, the Vietnam War, the Cuban Revolution, and the expansive force of Latin American insurgencies, of which he was one of its main organic intellectuals. In his particular case, the 1964 coup d'état in Brazil accelerated his political radicalization, but did not trigger it, since it is possible to verify that Marini already had a production of this type before and would continue developing it during and after the coup.3 If both Lenin and Marini summarized in their analyzes of the capitalist regime the asymmetric character between social formations, the levels of domination, conflicts, wars and exploitation, they always located their methodological axis on a world system scale plane.4 Coinciding with this general methodological perspective -which is none other than the one advocated by Marx from his Grundrisse-, Lenin and Marini approached the world system in various ways, highlighting in each case diverse and complementary angles of said system. If Lenin was the great theoretician of imperialism in its imperial centers, Marini ventured from the opposite side of said relationship, that is, he approached the same problem and the same questions from the perspective of dependency (also present in Lenin's writings). From both, complementary and mutually interdependent, foreshortenings they explored the various changes that the capitalist mode of production went through directly, on some occasions, indirectly, on others; in its implementation of the law of value and in its falling rate of profit. Both authors agree that the aforementioned law constitutes the heart of Capital.5 However, both also affirm that its empire was exercised not in a direct and linear way (as a superficial, depoliticized, and naive reading of Capital might suppose), but through convoluted mechanisms. For example, Lenin considered that the concentration and centralization of capital under the hegemony of the financial oligarchy gave a central role in the contemporary economy to the capitalist monopolies and that these, in turn, competing with each other for markets on an international scale, through the law of value, they applied planning within the production branch and the sector of the economy they controlled. For his part, Marini maintains, with a slight nuance, that the law of value governs each sector and branch of production of the value chain, but it is transgressed when exchanging between different spheres, which allows value to be transferred (that is, to cede a part of the extracted value and surplus value for free to the working class and its exploited workforce). Said transfer of value is not only due to the deterioration of the terms of trade (as ECLAC and developmentalist intellectuals such as Raúl Prebisch affirmed long ago). Nor exclusively to greater productivity present in the metropolitan capitalist economies, as the most orthodox Marxism insists to this day (notably Eurocentric: because it never explains how two analogous factories and clones, belonging to the same firm and the same capitalist monopoly, managing the same technology and identical constant capital, pay remarkably different wages in different social formations, with the same technology and with the exact same technical productivity!). The transfer of value, then, would be due to a combination of both, since the recolonization and ferocious plundering of the natural resources of the Third World -which has not disappeared to this today, except for those who only watch bourgeois TV news or read the newspapers of the system- made it possible to reduce the prices of goods produced by monopolies. In addition to the reduction in investment in constant capital, the reduction in investment in variable capital and, therefore, in this way the fall in the profit rate is counteracted (momentarily), a cancer that corrodes the world capitalist system from within. If Lenin emphasized the analysis of one pole of the world capitalist system in its imperialist phase, precisely the one that was leading the First World War when he studied and analyzed the phenomenon, Marini emphasized and explored the other pole of the same equation. The "strength" of his theory is located, precisely, in the study of dependent capitalism, its cycles of reproduction and accumulation, the gaps between production and consumption and, mainly, the compensation mechanisms that the lumpen and dependent bourgeoisie exercise, through the super-exploitation of the labor force of the proletariat and other subordinate classes, to temper each new extended cycle of capitalist dependence, under the horizon of the general crisis of capitalism in its imperialist phase. Therefore, unequal exchange and dependency, subordination to imperialism and super-exploitation of labor power, constitute mutually interconnected hypotheses in Ruy Mauro Marini's Marxist research. Only at the risk of caricature can they be unraveled as if they were juxtaposed. Furthermore, all of them, neither annul nor degrade, but rather complement, the macro analysis that Lenin made of imperialism as a world system in expansion. It is no coincidence that the political conclusion of both authors -derived in both cases from their empirical and theoretical research, but also from their militant political-ideological identity in the cause of revolutionary Marxism- aim to promote a socialist revolution with a global reach, without ever settling for partial changes on a regional or national scale. Open questions in the contemporary agenda Today's society is increasingly hyperconnected, contaminated and flooded with liquid ties, as Bauman says, even in its most intimate and everyday privileges (friendship, love, social and family ties). However, although Lenin's work on imperialism is a century old and Ruy Mauro Marini's more than forty years old, the questions formulated on a macro scale that the Asian politician opened, and the specific analyzes and developments that the Brazilian explored (to make observable how they were fulfilled and what specific role they assumed in the social formations and general analyzes of Lenin), continue to challenge contemporary ears. Has this international capitalist system of relations of exploitation, hierarchy, and various dominations, as well as the scandalous division of the world, ceased to take place? Are we living, as Hardt and Negri argued in Empire (2000), a flat and homogeneous capitalism, without centers or peripheries, without subordinations or dependencies, where all societies have a development with merely quantitative differences and their social formations are easily and kindly interchangeable? (Kohan, 2002; 2005). Has the conquest of dependent territories and the expropriation/dispossession of their natural resources stopped taking place? Is there no longer super exploitation? Did the asymmetry of the world system evaporate? Are there no longer wars over oil and other non-renewable resources such as gas, water, biodiversity, and so on? Have the issue of financial securities and derivatives and the artificial fabrication of external debts ceased to be mechanisms of spoliation and social discipline? Is there no longer dependency between societies? Are coups and military and intelligence interventions in the internal affairs of weak countries over? Are there no more national oppressions and does everyone enjoy cultural, linguistic, and national autonomy? What characteristics does international trade take? Have the antagonistic contradictions disappeared, and the very meaning of the socialist revolution been confined to the museum of history? Is resistance against imperialism no longer valid? Whatever the answer to each of these questions, and whether or not one maintains sympathy or antipathy for Lenin, Marini and their supporters, the questions of both remain open and deserve to be included in the contemporary agenda by the social sciences and popular militancy as a priority, as one of the main problems to be solved. References Aguilar Monteverde, Alonso (1983): Teoría leninista del imperialismo, Editorial Nuestro Tiempo, México D. F. Anderson, Kevin B. (2002): "El redescubrimiento y la persistencia de la dialéctica en la filosofía y la política mundiales", en Sebastian Budgen, Stathis Kouvelakis et al. (2010): Lenin reactivado. Hacia una política de la verdad, Akal, Madrid, pp. 119-144. Astarita, Rolando (2013): Economía política de la dependencia y el subdesarrollo. Tipo de cambio y renta agraria en la Argentina, Editorial de la Universidad Nacional de Quilmes, Buenos Aires. Bonefeld, Werner y Tischler, Sergio (comps.) (2002): A 100 años de ¿Qué hacer?, Ediciones Herramienta, Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Buenos Aires. Bottomore, Tom (1984): Diccionario del pensamiento marxista, Tecnos, Madrid. Carrère d'Encausse, Hélène (1999): Lenin, Fondo de Cultura Económica, Buenos Aires. Colectivo audiovisual del IELA: "Entrevista a Vania Bambirra sobre la obra e influencia de Ruy Mauro Marini", Brancaleone Film, Cátedra de Sociología, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBA), Universidad Federal de Santa Catarina, Brasil, <http://www.cipec.nuevaradio.org> [25/12/2016]. Deutscher, Isaac (1975): Lenin: Los años de formación, Ediciones ERA, México D. F. Díez del Corral, Francisco (1999): Lenin: Una biografía, El Viejo Topo, Barcelona. Gruppi, Luciano (1980): El pensamiento de Lenin, Grijalbo, México D. F. Hill, Christopher (1965): Lenin, Centro Editor de América Latina, Buenos Aires. Íñigo Carrera, Juan (2017): La renta de la teirra. Formas, fuentes, apropiación, Imago Mundi, Buenos Aires. Justo, Juan B. (1969): Teoría y práctica de la historia, Líbera, Buenos Aires. Publicado originalmente en 1909. Kohan, Néstor (1998): Marx en su (Tercer) Mundo, Biblos, Buenos Aires. Kohan, Néstor (2002): Toni Negri y los desafíos de "Imperio", Campo de Ideas Madrid. Kohan, Néstor (2005): Toni Negri e gli equivoci di "Imperio", Massari Editore, Bolsena. Kohan, Néstor (2014a): "Entrevista a Orlando Caputo sobre la obra e influencia de Ruy Mauro Marini", Cátedra de Sociología, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBA), Brancaleone Film, <http://www.cipec.nuevaradio.org> [25/12/2016]. Kohan, Néstor (2014b): Fetichismo y poder en el pensamiento de Karl Marx, Biblos, Buenos Aires. Kohan, Néstor (2015): "Entrevista a Theotonio Dos Santos sobre la obra e influencia de Ruy Mauro Marini", Cátedra de Sociología, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBA), Brancaleone Film, <http://www.cipec.nuevaradio.org> [25/12/2016]. Krupskaia, Nadiezhda (1984): Lenin: su vida, su doctrina, Editorial Rescate, Buenos Aires. Lenin, Vladímir I. (1894): "¿Quiénes son los "amigos del pueblo" y cómo luchan contra los socialdemócratas?", en Vladímir I. Lenin (1973): Obras, t. I, Editorial Progreso, Moscú, pp. 11-39. Lenin, Vladímir I. (1916): "La revolución socialista y el derecho de las naciones a la autodeterminación. Tesis", en Vladímir I. Lenin (1959-1960): Obras Completas, t. 22, Editorial Cartago, Buenos Aires, pp. 1-19. Lenin, Vladímir I. (1960): "El imperialismo, fase superior del capitalismo. Esbozo popular", en Obras Completas, t. 22, Editorial Cartago, Buenos Aires, pp. 161-210. Publicado originalmente en 1917. Lenin, Vladímir I. (1974a): Cuadernos filosóficos, Editorial Ayuso, Madrid. Lenin, Vladímir I. (1974b): Diario de las secretarias de Lenin. Contra la burocracia, Pasado y Presente, Buenos Aires. Lenin, Vladímir I. (1984): Cuadernos sobre el imperialismo, 2 t., Editorial Cartago, Buenos Aires. Lenin, Vladímir I. (1987): Testamento político, Editorial Anteo, Buenos Aires. Lenin, Vladímir I. (1930): Leninskaia Tretadka, archivo n.º 18 674, Instituto Lenin, Moscú . Lenin, Vladímir I.; Ancona, C. et al. (1979): Clausewitz en el pensamiento marxista, Pasado y Presente, México D. F. Lenin, Vladímir I.; Hobson, John A. y Harvey, David (2009): Imperialismo, Editorial Capitan Swing, Madrid, pp. 399-529. Lukács, György (1968): Lenin, la coherencia de su pensamiento, Editorial La Rosa Blindada, Buenos Aires. Marini, Ruy Mauro (1974): Dialéctica de la dependencia, Serie Popular, Editorial ERA, México D. F. Marini, Ruy Mauro (2007): Proceso y tendencias de la globalización capitalista, Prometeo-CLACSO, Buenos Aires. Marini, Ruy Mauro y Millán, Margará (1994a): La teoría social latinoamericana. Textos escogidos, 3 t., Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), México D. F. Marini, Ruy Mauro y Millán, Margará (1994b): La teoría social latinoamericana. Textos escogidos, 4 t., Editorial El Caballito, México D. F. Edición comentada. Marx, Karl (1973): El Capital, t. I, Editorial Cartago, Buenos Aires. Publicado originalmente en 1867. Sacchi, Hugo (1990): Lenin, Centro Editor de América Latina, Buenos Aires. Service, Robert (2001): Lenin, una biografía, Siglo XXI, Madrid. Traspadini, Roberta y Stedile, João Pedro (2005a): Ruy Mauro Marini: Vida e obra, Expressão popular, São Paulo. Traspadini, Roberta y Stedile, João Pedro (2005b): Ruy Mauro Marini: Vida y obra, Claudio Colombani (traduc.), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), <http://www.marini-escritos.unam.mx> [28/11/2016]. Trotsky, León (1932): "Historia de la Revolución rusa", 2 t., Marxists Internet Archive, <https://www.marxists.org/espanol/trotsky/1932/histrev> [28/11/2016]. Weber, Hermann (1985): Lenin, Salvat, Barcelona. Zetkin, Clara (1975): Recuerdos sobre Lenin, Grijalbo, México D. F. AuthorNéstor Kohan is a philosopher, intellectual, and an Argentinean militant Marxist, he also forms part of LatinAmerican Marxist. As part of this tradition of political thought and culture he has published 25 books on the topic of social theory, history, and philosophy. He actively participates as an investigator for CONICET and is a professor at the University of Buenos Aires. This article was republished from Granma. Archives April 2022

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed