|

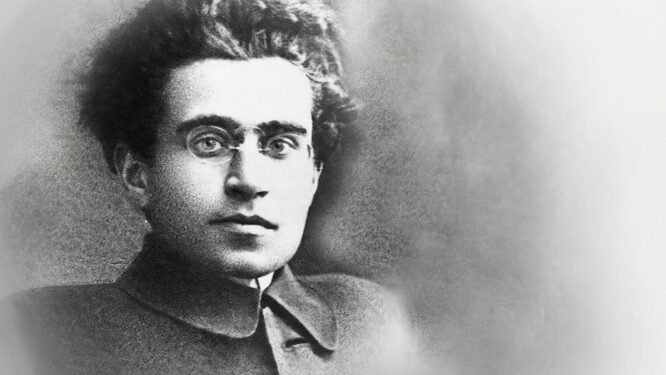

With capitalism’s rapid descent into environmental catastrophe, epidemiological crises, and neo-fascist forms of governance, the forceful necessity of a socialist revolution seems evident. However, the specific modes of realization of such a historical change remain elusive. Decades of neoliberalism have resulted in a sharp decline in mass movements and struggles that represent vibrancy of subaltern praxis and popular power. The vast reservoirs of creativity, solidarity and existential resoluteness have been dealt a solid blow by undiminished austerity attacks which target the core of human dignity. And this explains the prolonged collapse of long-term imagination and revolutionary perspectives on the international Left. An article in the April 2021 issue of “Reform and Revolution” - a magazine run by a Marxist caucus within Democratic Socialists of America - argues: “reforms are only won through struggle, and…if our class organizes on a larger scale and in a direct fight for political power, far more can be won.” This line of reasoning closely resembles Erik Olin Wright’s proposed strategy to “erode” capitalism. What these viewpoints share in common is a failure to understand the structural texture of capitalist totalities, overlooking the interlinked nature of the various elements which compose such social formations. More specifically, a reformist perspective is theoretically underdeveloped, being incapable of locating the particular positions of the political and social levels within capitalism. State-forms in East and WestIn his famous “Prison Notebooks”, Antonio Gramsci once wrote: “In the East, the State was everything, civil society was primordial and gelatinous; in the West, there was a proper relationship between State and civil society, and when the State trembled a sturdy structure of civil society was at once revealed. The State was only an outer ditch, behind which there was a powerful system of fortresses and earthworks: more or less numerous from one State to the next, it goes without saying - but this precisely necessitated an accurate reconnaissance of each individual country.” In this passage, Gramsci affirms the existence of a strong state-form in the West that includes, importantly, the multiple articulations and mediations of a mature civil society. The real subsumption of society under capital in the West provides the basis for social cohesiveness. This may be a corollary of the mediating role of representative institutions, or the more abstract phenomenon of social democratization - juridical equality that allows increased national political and economic participation. In the East, by contrast, the state lacks the complex of defensive trenches that a developed and articulated civil society can provide to the state in the West, and which helps to resist the immediate eruption of conflicts in the sphere of production into the political terrain. Gramsci’s comparison of advanced capitalist formations - with high state viscidity - to politically disarticulated and heterogeneous ones, characterized by arrangements of pre- or non-capitalist elements alongside capitalist ones was borrowed from Vladimir Lenin. Lenin’s “Report on War and Peace” - published in 1923 - contained the following: “The revolution will not come as quickly as we expected. History has proved this, and we must be able to take this as a fact, to reckon with the fact that the world socialist revolution cannot begin so easily in the advanced countries as the revolution began in Russia - in the land of Nicholas and Rasputin, the land in which an enormous part of the population was absolutely indifferent as to what peoples were living in the outlying regions, or what was happening there. In such a country it was quite easy to start a revolution, as easy as lifting a feather. But to start without preparation a revolution in a country in which capitalism is developed and has given democratic culture and organization to everybody, down to the last man - to do so would be wrong, absurd.” Gramsci’s differentiation of state-civil society relations in the East and West was used by reformist thinkers - most prominently Eurocommunists - for patently non-revolutionary purposes. They asserted that insofar as the Western state was based largely in the civil society, capitalism could be slowly weakened through cultural and parliamentary struggles against bourgeoisie hegemony. Thus, Nicos Poulantzas was writing about his hopes of building democratic footholds in the capitalist state in the 1970s in Europe, when labor was relatively strong and social democratic parties seemed to be able to take over the administrations of different western European countries. Nevertheless, his hopes never materialized. Integral StateThe reformist reformulations of the “Prison Notebooks” are aided by a selective reading. According to Gramsci, the Western bourgeoisie’s full-fledged articulation of a hegemonic project reproduces itself at the institutional scale in the form of a qualitatively new apparatus - the “integral state”. The state is no longer an intermittent entity in quotidian life. Instead, it percolates into the micro-pores of society, penetrating into the sumps of civil society. Gramsci identifies civil society closely with the “consent given by the great masses of the population to the general direction imposed on social life by the dominant fundamental group”. In addition to civil society, there also exists political society, comprising the “apparatus of state coercive power which ‘legally’ enforces discipline on those groups who do not ‘consent’ either actively or passively.” As Gramsci further notes, “This apparatus is, however, constituted for the whole of society in anticipation of moments of crisis of command direction when spontaneous consent has failed” - thus, the integral state equals “political society + civil society, in other words hegemony protected by the armour of coercion”. Here, the distinctions between political society and civil society are heuristic, not organic and ontological. In reality, both the components of the integral state exist as dialectical moments in a wider picture of fundamental unity. This point can be clarified through a brief delineation of the contours of hegemony. In “Dominance without Hegemony”, Ranajit Guha developed a useful analytical schema. Hegemony involves a relation of Dominance [D] to Subordination [S] - and these two terms imply each other. Both aspects of power have their correlates: Dominance can take the forms of Coercion [C] and Persuasion [P], whereas Subordination” can take the form of Collaboration [C*] and Resistance [R]. In the words of Guha, the “mutual implication of D and S is logical and universal in the sense that, considered at the level of abstraction, it may be said to obtain wherever there is power, that is, under all historical social formations irrespective of the modalities in which authority is exercised there.” But the specific mix of coercion, persuasion, collaboration and resistance is contingently variable in different historical situations. In any given society, and at any given point in time, the relation D/S varied according to what Guha termed - following the terminological style of “Das Kapital” - the “organic composition” of power, which depended on the relative weights of C and P in D, and of C* and R in S, which were always, he argued, contingent. Hegemony was a condition of dominance in which P exceeded C. “Defined in these terms, hegemony operates as a dynamic concept and keeps even the most persuasive structure of Dominance always and necessarily open to Resistance”. But at the same time, “since hegemony, as we understand it, is a particular condition of D and the latter is constituted by C and P, there can be no hegemonic system under which P outweighs C to the point of reducing it to nullity. Were that to happen, there would be no Dominance, hence no hegemony”. This conception, he noted, “avoids the Gramscian juxtaposition of domination and hegemony as antinomies”, which had “alas, provided far too often a theoretical pretext for a liberal absurdity - the absurdity of an uncoercive state - in spite of the drive of Gramsci’s own work to the contrary”. As is evident, hegemony - unlike reformist conceptions - only constitutes the social basis of power in the state (conceived in a limited sense, as governmental apparatus); expressed in terms of the dialectical unity of the integral state, dominance in political society depends upon a class’s ideological capacities in civil society. Given the earthworks and trenches that exist in the West, a class that aspires to be hegemonic must pass through the different, yet unified, moments of civil and political hegemony before reconstituting the state - the final war of maneuver. When the integral state is understood in all its comprehensiveness, civil society becomes the terrain upon which social classes compete for social and political leadership or hegemony over other social classes. Such hegemony is guaranteed, however, in the ultimate instance, by capture of the legal monopoly of violence embodied in the institutions of political society. Hence, the political society is a condensation of the social forces in civil society that are themselves overdetermined by economic interests and relations of forces originating from the political arena. The state apparatus of the bourgeoisie can be defeated only when the proletariat has deprived it of its social basis through the construction of an alternative hegemonic narrative and its concretization in a corresponding hegemonic apparatus. Contemporary reformists deny the indispensability of the latter. Hence, rather than locating hegemony in either civil society or political society, or characterizing hegemony as invariably involving consent by the ruled to their subordinate status, or seeing hegemony as a process working at the molecular level in an almost non-political way, we need to see hegemony as a way of amalgamating social forces into political power. The exercise of hegemony, initially done within civil society, must also have a substantive effect upon political society - because political society itself is integrally intertwined with civil society and its social forces, as their mediated, higher forms. In fact, any attempt for the attainment of hegemony within civil society has to progress towards political hegemony in order to maintain itself as such. Dual Power StrategyBy now, it should be obvious that Gramsci posits no deep-seated differences between East and West, as far as the state goes. Despite any ease of access to political power on one side of the divide, there is still - to use Gramsci’s phrase - that intense “labour of criticism” (part and parcel of a lengthy war of position) which needs to be carried out in any historical process of intellectual and moral reform; hegemony needs to be molded in a manner that reaches popular consciousness. Any conquering of a “gelatinous” state needs to be followed by this work. Thus, different historical formations are at different levels in terms of their development of civil society. These formations purely differ in the quality of the relationship between state and civil society. Now, the types of the state-civil society linkages in the West depend crucially upon material apparatuses. In “The Antinomies of Antonio Gramsci”, Perry Anderson turned his emphasis away from culture as the mechanism of consent to “the general form of the representative State,” which “deprives the working class of the idea of socialism as a different type of State.” Communication, consumerism, and “other mechanisms of cultural control” could only reinforce, in a complementary and secondary manner, this more fundamental mechanism, which belonged to the sphere of the state itself. The bourgeois state abstracted the population from its class divisions, “representing” individuals as equal citizens: “[I]t presents to men and women their unequal positions in civil society as if they were equal in the State. Parliament, elected every four or five years as the sovereign expression of popular will, reflects the fictive unity of the nation back to the masses as if it were their own self-government.” The “juridical parity between exploiters and exploited” conceals “the complete separation and non-participation of the masses in the work of parliament.” The consent extracted by the bourgeois state “takes the fundamental form of a belief by the masses that they exercise an ultimate self-determination within the existing social order.” The belief in equality of all citizens, that is, in the absence of a ruling class, produced by the institutions of parliamentary representation, is the structure of consent found in a developed capitalist society. Since parliamentary apparatuses are themselves responsible for the preservation of capitalist society, a “democratic road to socialism” ends up reinforcing the ideology of bourgeois democracy. Hence, socialism will require not the uncritical takeover of the existing state apparatuses but their dismantlement through the cultivation of new institutions of grassroots democratic popular power. This revolutionary perspective is described as a dual power strategy because it promotes new centers of popular power outside of (an in opposition to) the apparatuses of the old state. But such a revolutionary position is ignored by present-day reformists who neglect the conjoined status of civil society and political society. AuthorYanis Iqbal is an independent researcher and freelance writer based in Aligarh, India and can be contacted at [email protected]. His articles have been published in the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and several countries of Latin America. Archives July 2021

2 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed