|

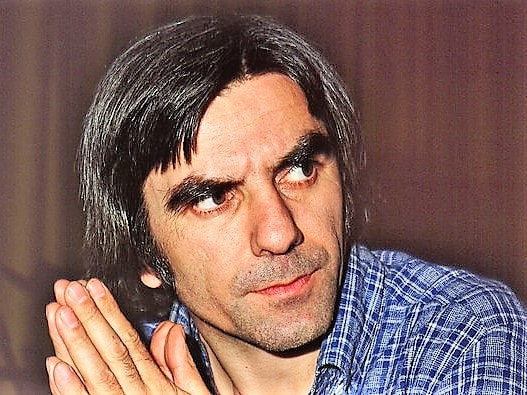

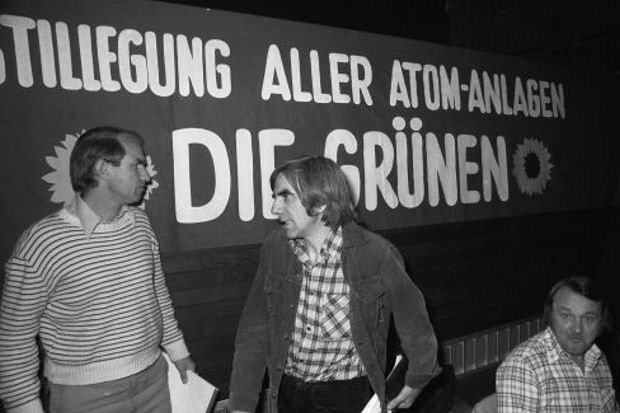

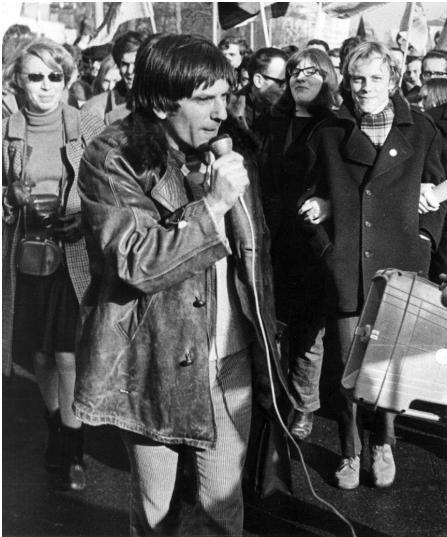

10/1/2021 A conversation between Günter Gaus and Rudi Dutschke. Translated with comments by Vince K.Read NowA conversation between Günter Gaus and Rudi Dutschke[1]Original broadcast date: December 3rd, 1967. Rudi Dutschke, born March 7th, 1940 in Schönefeld (East Germany), died December 24th, 1979 in Arhus (Denmark). Bio[2]Dutschke completed his Abitur in 1958 and trained as an industrial clerk. He refused to serve in the National People’s Army. Later, he studied sociology in West Berlin and joined the Socialist German Student Union (SDS). Dutschke soon became a leading figure in the Extraparliamentary Opposition (APO) and in the student movement. He gave countless interviews, talks, and essays. In April of 1968, serious riots followed in the wake of an assassination attempt against him. These riots mainly targeted the Springer Press, which was seen as complicit in this act of violence because of its previous reporting on the APO. Dutschke later became a lecturer in Arhus, where he died from the late consequences of his gunshot wound. This interview was broadcast December 3rd, 1967. Gaus: This evening, you will see an interview that I conducted with Rudi Dutschke a few weeks ago. Rudi Dutschke is 27 years old, he left East Germany some time ago for political reasons, and he is currently a student of sociology at the Free University of Berlin. He is the most eminent spokesman for a movement of radical students who not only want to reform West Germany’s colleges and universities but also seek to upend the entire social order as we know it. These students are a small minority. The great uproar that precedes them cannot obscure this fact. The overwhelming majority of German students is likely still apolitical. Most of them are not even interested in higher education reform to the extent that we should want them to be. And within that minority of students who take an interest in these bitterly-desired, overdue reforms, Dutschke’s followers are still quite a small group. Should this be any reason not to concern ourselves with him? Dutschke and his friends must admit that their style of argumentation occasionally makes it difficult to see them as serious conversational partners. In my view, this should not prevent us from making sense of what these young revolutionaries want to be – what they consciously desire to be – in a time when one can no longer take the idea of revolution seriously. One asks what these young revolutionaries really have in mind. I think this is the reason why an interview with Rudi Dutschke has value. This will not have as much to do with concrete references to current events as with the general principles that guide Dutschke’s thinking. These are the principles he is attempting to impose on our society. With that, we welcome you to our program: “On the record – Rudi Dutschke.” Mr. Dutschke, you would like to transform the social order of the Federal Republic of Germany. According to you, everything must be changed from the ground up. Why? Dutschke: Yes – let us start by going back to the year 1918. That was when German councils of workers and soldiers first secured the 8-hour working day. In 1967, our blue-collar and white-collar workers alike have been spared a measly four to five hours of work per week. And this despite a colossal development of productive forces, a development of technical achievements that could theoretically bring about an equally-colossal reduction in working hours. In the interest of maintaining the established system of rule, this historically-actualized reduction in working hours has been put on hold in order to maintain a state of unconsciousness. This unconsciousness stands in connection with the length of the workday. Here is an example: after World War II, the two German governments spoke incessantly about unification. Over twenty years later, we have no unification. Instead, we have systematically received a series of regimes that one may call institutionalized lying instruments, in a manner of speaking. These are instruments of half-truth, of distortion – the people are not being told the truth. No dialogue is being established with the masses, no critical dialogue that could explain what is happening with our society. Now that the economic miracle[3] has come to an end, why has there been no progress on the issue of unification? One speaks of ‘humanitarian concessions’ while referring to nothing other than the maintenance of political rule. Gaus: Mr. Dutschke, why do you believe that the changes you’re looking for cannot be achieved by working with the existing parties? Dutschke: There has been a long tradition of parties: social-democratic, conservative, liberal. Without going into too much historical detail, we have had a very clear development of parties since 1945, the result of which is that they are no longer instruments for raising the consciousness of all the people in our society. They are now merely instruments for stabilizing the prevailing order; they make it possible for a particular layer of the apparatus of party functionaries to reproduce themselves within their own framework, and thus the possibility that upward pressure and upward attainment of consciousness could prevail qua party institution has already become impossible. I think that many people are no longer willing to participate in these parties. Even those who still vote are ill at ease with the parties that exist. And… build another two-party system, and it’s over for good.[4] Gaus: We’re about to touch on your conceptions for a political society, and we will certainly have more to say about that. For now, I’d like to know what sets you apart from the prevailing political system. If one studies what you have written and said thus far, Mr. Dutschke, one concludes that the opposition embodied by you and your friends in the SDS[5] is not only extraparliamentary, but also anti-parliamentary. This was my impression, at least. One question: do you agree with this finding? Do you believe that the parliamentary system is unusable? Dutschke: I regard the existing parliamentary system as unusable. That is, we have no representatives in our current parliament who express the interests of the population – their actual interests. Now, you might ask: what actual interests? But there are in fact demands, even within the parliament. There are demands for unification, for securing jobs and public finances, for an economy that can bring everything into order. Those are all demands, and the parliament is responsible for fulfilling them. But it can only fulfill them by establishing a critical dialogue with the public. Well, there is currently an absolute division between the representatives in the parliament and the people, who are being kept in a state of disempowerment.[6] Gaus: For the moment, we have both agreed to make a record of your assertions before we begin discussing them. Please tell me: how would your ideal society organize, manage, and govern itself? Dutschke: The society we strive for is the result of a drawn-out process,[7] which means that we cannot make grand sketches of how the future will look. We only can say that it will have its own structuration that differs from the current one in principle. Gaus: How so? Dutschke: In the sense that under the current conditions, we have elections every four years, and we have the opportunity to affirm the existing parties. We have ever fewer chances to choose new parties, and thus fewer alternatives to the prevailing order… Gaus: The NPD[8] is one counterexample. Dutschke: The NPD is not a counterexample – its emergence is inseparable from the unease towards existing parties on one hand and the end of the reconstruction period (uncritically: the so-called economic miracle) on the other hand. Both factors have enabled the advent of the NPD. But this does not mean that the NPD has no chance of winning majorities among the masses… Gaus: Let’s return to your ideal conception of society, which you want to construct politically. Dutschke: The fundamental difference is that we’ve begun to establish organizations that differ from traditional party structures. For one, there are no active career politicians within our ranks. We have no party apparatus. The needs and interests of participants in this institution are represented, whereas the parties contain an apparatus that manipulates the interests of the people rather than expressing them. Gaus: When your revolutionary movement becomes large enough and adapts to the sort of apparatus that naturally belongs to large organisms, how do you want to avoid that? Dutschke: That is an assumption on your part; I mean, there is no natural law stating that an evolving movement must have an apparatus. It depends on the movement and whether it can join the various levels of its development with the changing levels of consciousness. To put it more precisely, when we succeed in structuring this drawn-out transformation as a process of attaining consciousness among the individual members of the movement, we will achieve the conditions that make it impossible for the elites to manipulate us. That there is a new class… Gaus: You assume that the human being is absolutely capable of education, that human beings can become better. Dutschke: I assume that the human being is not condemned to remain subject to a blind interplay of historical coincidences. Gaus: People can take history into their own hands? Dutschke: They have always done so. They simply haven’t done so consciously yet. And now they must finally do so consciously – they must take control of history. Gaus: How do these new human beings govern themselves, who leads them, how do they determine who leads them, and how do they vote their leader out of office? Dutschke: They lead themselves – and this self-organization doesn’t mean that I am letting strangers decide things for me. When I say that people have always made history for themselves, albeit not consciously, this implies that if they were to do so consciously, the problem of elites and apparatuses assuming an independent existence would not arise. The problem consists in recalling elected officials and in having the ability to do so at will, and also in being conscious of the need for a recall. Gaus: Which basic characteristics need to be ‘excised’ from human beings so that they can achieve what you’re expecting from them? Dutschke: Not a single one. It’s just that the repressed characteristics must finally be set free. I am referring to the repressed capacity of mutual aid, the ability for people to transform their understanding into reasoning, and also their ability to understand the society they live in rather than being manipulated by it. Gaus: How do you and your friends want to bring about this level of consciousness within humanity? Dutschke: We’ve started to develop a method by which an education on social facts in the whole world and in one’s own society are paired with actions. By mediating and pairing this education – a systematic enlightenment – with what is happening, with all the daily events that are repressed in the newspapers, the radio broadcasts, and even on television; there are 122 countries in the world… when you open the BILD newspaper, you see one country at most, and you don’t even see what is happening in this country. This is a phenomenon not of information overload but of the systematic suppression of information and the non-structuring of information that is given. We want to break this apart. We want to share actual news about what is happening in the world, to enlighten people, and to lead campaigns that produce a new public sphere that takes note of this information, understanding that the existing public sphere is not the only option. Gaus: What distinguishes your program of “revolutionary enlightenment” and your political goal of remodeling the world from the earlier revolutionary movements? What’s the difference? Dutschke: I would say that the decisive difference is the historical situation we’re working with. In earlier epochs, revolutionaries worked mainly within the framework of the nation-state. Our work today deals with world-historical conditions in a very real sense. The Federal Republic of Germany can by no means be called a nation-state; we find ourselves in a system of international relationships. We are in NATO. Our populace has no idea what this means for the future. In 1970, one half of the world population will possess only one sixth of their labor value in the form of goods.[9] Revolutionaries in various continents are working to alleviate their misery. We are stuck in this web, and we need a world market that doesn’t constantly impoverish one half of the world, producing even more conflicts in the process. This has to be dismantled, this is what we find ourselves in, and in this respect, we differ fundamentally from various situations… Gaus: The communist revolution was supposed to be international, at least in theory. Dutschke: Yes, and it couldn’t manage that in real history. When the Communist International was beginning to form in 1919, of course the idea of an international class struggle existed. But really, there wasn’t even a true movement in the various continents… Gaus: Do you believe that the nation-state has been overcome across the world as an obstacle to such an international movement? Dutschke: The nation-state has not been overcome as an obstacle. It is trapped in the human consciousness. The problem lies in eliminating this ideological obstacle, in making this international mediation visible – both the way we are embedded in it and the way we can get out of it. Gaus: But that’s the same problem that the communists had in 1919. Dutschke: But they wouldn’t have been able to solve it back then. We can solve it today with help from telecommunications and other forms of global networking. Gaus: Va bene. Mr. Dutschke, I’m assuming that the consciousness of people in highly-industrialized states today is determined by an insight into the futility of revolutions. Note well: these are industrialized states, not developing countries. The two great European revolutions, the French and the Russian, have undoubtedly transformed political and social relations, but the practically Edenic ‘end stage’ of each (the long-term goal) was never attained. The revolutionaries were frozen in their tracks, sometimes struck by dreadful side effects. Mr. Dutschke, what makes you think that your revolution will be different, that is, more complete? How will you stop your long-term goal from vanishing in the distance before you reach it? Dutschke: We know the conditions under which the Russian Revolution faltered.[10] It’s a historical problem; we have an explanation for why it didn’t work. Why Lenin’s theory of the party appeared as a notable roadblock in 1921. Why the lag in industrialization in Russia was a condition for this failure. These are factors that we can name. There is no guarantee that we won’t fail in the future. But if a free society is unlikely, that’s all the more reason to work hard to create a historical possibility for it, even if success is not a given. It’s a question of human will whether we’re able to succeed, and if we don’t succeed, we’ve wasted one period of history. Maybe the alternative is barbarism! Gaus: Now that’s the point I’d like to address, Mr. Dutschke: on the way to your long-term goal, however humanitarian and well-intentioned that goal may be, it may happen that you have to take highly inhumane measures. To avoid interruptions along the march to your distant paradise, there is no way you’d be able to avoid the possibility of having to construct prisons and concentration camps. Dutschke: That’s what minority revolutions had to contend with. The difference from previous revolutions is also the fact that our process of revolution will be a very long one, a long march. During this long march, either the problem of becoming conscious will be raised and then solved, or we will fail. Gaus: If I understand correctly, your revolution will develop in very long stages, and each of these stages will only be completed once humanity has reached the level of consciousness necessary for that stage.[11] But once this has been done, there is no need for prisons or concentration camps. Is that correct? Dutschke: Yes. That’s the precondition for doing away with prisons as prisons. Gaus: How long is the march? Will you get there in 1980? Dutschke: You see, there’s one data point in particular. Back in 1871, there was the Paris Commune… Gaus: Yes; that’s an exemplar for you! Dutschke: An exemplar for us. The dominion of producers over their products. No manipulation, regular elections and recalls, and so on… Gaus: I know. Of all the accompanying phenomena, it was the decisive one… Dutschke: The decisive model for the future, one we must keep reaching for. But the length of this fight won’t be a deterrent for us. It will take a long time, but many people are already leading the fight, and not only from within the established institutions. Gaus: We’ll eventually get to discussing the size of your movement. First, I’d like to ask another question. Mr. Dutschke, you were born in 1940, and I believe the key distinction between your generation and those who are currently in their 40s and 50s is that you, the youth, haven’t come to the realization over the past several decades that ideologies have been depleted. I mean to say that your generation is ideologically capable. Do you accept this generational difference? Dutschke: I wouldn’t think of it as a generational difference; I would say that there are a few grounding experiences. But these aren’t necessarily a generational difference. Grounding experiences can be processed in a variety of ways. To me, the key difference would lie in this variety of approaches. And so before 1914, there was certainly a grounding experience, but it wasn’t directed against the political institutions. We, however, do direct ourselves against them. Gaus: Still, I would argue that every ideologically stamped politics of our day, in our industrialized states, is fundamentally inhuman. It forces people to follow a route that is mapped out in advance so that later generations may be better off. Dutschke: No, nothing is being mapped out in advance. The act of mapping out is precisely the hallmark of the established institutions, which force people to accept something as fact. Our starting point is the self-organization of individual interests and needs, this is the form of the problem of… Gaus: But this presupposes a rise in human consciousness. At the very least, you have to convince people to accept this rise in consciousness. People won’t undertake it voluntarily; you must bring them to it. What will you do if someone says they’d rather sit at home every evening in peace, watching crime shows on TV, instead of letting Mr. Dutschke and his friends ‘enlighten’ them? Dutschke: We do not claim to be raising the consciousness of the whole population. We know that for now it’s possible to enlighten minorities that historically have the chance of becoming majorities. As of today, we are still few. But that doesn’t exclude the possibility that more and more people – especially now at the end of the so-called economic miracle, with many international events on the docket that have the power to raise consciousness – will perhaps see our insights as the correct ones. Gaus: I’d like to make two comments on that. Firstly: how do you – as a minority revolution – plan to avoid having to repress majorities if you ever come to power? How do you avoid the danger that other revolutions have been subjected to, according to your own definition? Dutschke: Nowadays, only right-wing minorities can win, not left-wing ones. A right-wing minority could win in Greece.[12] But there will be no chance for left-wing minorities to win in the organized late capitalism of today, where the international counterrevolution has already built all the necessary conditions for avoiding minority revolutions. That’s good, though, that’s all right. Gaus: This means that the counterrevolution saves you from the danger… Dutschke: … of becoming like the Bolsheviks. Gaus: I understand. And a second question along those lines: what gives you the confidence to assume that people who are distraught by recessions, economic decline, and unemployment in places like the Federal Republic will listen to your appeal? You’re telling them: “You must begin to understand yourself and your situation better.” Why should they choose this rather than the more comfortable solution offered by leaders of parties like the NPD? They don’t ask people to learn anything; they just have a ready-made prescription. Dutschke: They don’t have any ready-made prescriptions to offer. They only offer irrational and emotional forms of appearance.[13] Gaus: That’s the danger I’m speaking of. Dutschke: Yes, that’s the danger, but danger is precisely the starting point of our work. In the process of doing our work, we are continually reducing the chances that powerful NPD-like leaders will be able to captivate the masses. Instead, we are improving the chances that awareness can increase, perhaps as the starting point for left minorities in the sense of teaching the majority. This is currently not the case. Gaus: Mr. Dutschke, the bourgeois German youth of the “Great Peace of 1914” – as I like to call it – were so tired of the prevailing conditions of the era that they called for a molten bath[14] in the proverbial sense, which they ultimately got at Langemark.[15] Today, your circle of friends is calling for two, three, many Vietnams.[16] Out of this will emerge the New Man who saves the world. Is this a parallel? Dutschke: No, that isn’t a parallel. That’s the call of the revolutionaries in the Third World, in the underdeveloped world. This is our call: get out of NATO now so that we don’t end up in this “molten bath” ourselves. That is, if we are still complicit in 1969, this means that among other things we will continue participating in the international counterrevolution in 1970-71, which has no choice but to crush movements in the Third World, and this includes Latin America, Africa, and Asia. America is no longer able to crush revolutionary social movements all on its own; Greece is now on the verge of doing the same.[17] Sooner or later – and this isn’t far away – the Federal Republic will be mired in this too if it continues to recognize NATO as the ultimate constituent of its political authority. Gaus: So, you brush off the possibility that some of your supporters are merely bored of the welfare state and are following you for that reason? Dutschke: For us, boredom can be a starting point for political consciousness. But this is boredom made aware: why are we bored, what bothers us about the state, what can be improved, what needs to be abolished. This is how boredom becomes consciousness. And this is how a politically productive power against our society is formed. Gaus: Mr. Dutschke, you hail from the region of Brandenburg, you’ve lived in East Germany, and as a student you were a member of the youth division of the Evangelical Church, which was occasionally suppressed with force in the GDR. You once described yourself as being influenced quite a bit by Christian socialism (at least that’s how I read it), and you even had the mettle to refuse military service in the National People’s Army. If it were necessary, would you fight for your revolutionary goals with a weapon in your hand? Dutschke: The clear answer: if I were in Latin America, I would fight with a weapon in my hand. I am not in Latin America; I am in the Federal Republic of Germany. We are fighting so that weapons never have to be used. But that isn’t up to us. We aren’t the ones in power. People are not aware of their own destiny. And so, if we don’t exit NATO by 1969, if we are mired in international conflicts, we will certainly resort to weapons while the Federal Republic’s troops are fighting in Vietnam, Bolivia, or elsewhere. If that’s the case, we will also be fighting in our own country. Gaus: That’s what you want to do? Dutschke: Who was it that conjured up this misfortune? Not us; we were the ones who tried to avoid it. It’s up to the prevailing powers to avoid this future misfortune and to develop political alternatives. Gaus: Why don’t you step out of politics? Wouldn’t that be a better expression of pity for the poor devils for whom these terrible times are looming? Why don’t you rather say, “we can’t change it, just let it go?” Dutschke: We can change it. We aren’t hopeless fools of history, incapable of taking destiny into their own hands. They’ve tried to convince us for centuries that this is all we are. Many historical signs point to the fact that history itself is not an endless roundabout where the negative side always triumphs. Why should we stop just before this historical possibility and say: “Let’s step out now, we’re not going to make it… The world is going to end sooner or later.” Quite the opposite. We can give shape to a world that has never been seen before, a world that knows no war or hunger, and we can make that happen across the whole planet. That is our historical possibility. Why step out there? I’m no career politician. We are simply people who don’t want the world to continue down its current path. That’s why we’ve been fighting, and that’s why we’ll continue to fight. Gaus: And if there are people who wish to step out, will you force them to stay? Dutschke: No one is fighting alongside us without doing it out of their own awareness. As for those who conjured up all this misery… the degree of violence has been determined by the other side, not by us. And that’s the point of departure for our own estimation of the role of violence in history. Gaus: If I were able to interview Lenin in 1907, or better yet, in 1903 – before the first Revolution – wouldn’t he have made arguments very similar to yours? Dutschke: No, I don’t think so. Lenin certainly couldn’t have made arguments like these. He was lucky enough to have a clear (or relatively clear) picture of class society and a proletarian class ready to be set into motion. We don’t have this picture. We can’t have one because our process is much more complicated, longer, and more difficult. Gaus: That’s correct. But in one point, he may have had similar arguments, namely in the fact that the goal of his revolution was making the world a peaceful place. Dutschke: It is certainly a goal of socialism, while it exists, to create a world where war has been eliminated. Gaus: Yes. So, Lenin would have made arguments like yours in this point. Dutschke: Only in the continuity of international socialism, which began long before Lenin. Gaus: Correct. And you say that you won’t follow the same path as Lenin and his revolution because you never want to repress majorities as a minority. Dutschke: We can never take power as a minority, and we don’t want to. That’s our big opportunity. Gaus: That’s true. What led you away from the evangelical basis for your first social-political engagements, namely your membership in the youth division of the Evangelical Church? Dutschke: Religion really played a major role for me. I think it’s a fantastic explanation of the essence of human beings and their possibilities. But this fantastic explanation must be actualized in real history. And so, that which I understood in the past as a Christian now plays a part in my political work, which may include realizing peace on earth. If you want to put it that way. Gaus: You’re still a Christian? Dutschke: What is a Christian? These days, Christians and Marxists agree on these crucial questions such as peace, and they share a virtually emancipatory interest. We are fighting for the same goals. The priest in Columbia who’s at the forefront of the guerillas, fighting with a weapon in his hand, is himself a Christian![18] And the revolutionary Marxist elsewhere is also one… Gaus: But what role does the transcendental play for you? Dutschke: The “God question” was never a question to me. The most critical, historically grounded question was this: what was Jesus actually doing back then? How did he want to change his society, and what methods did he use? That was always the key question. The question of transcendence is for me a historical one as well.[19] How to transcend the current society, how to create a new framework for a future society. Maybe that’s a materialistic form of transcendence… Gaus: Do you think that compassion is the mainspring of your political activity? Dutschke: I don’t think compassion is the single most important thing. I think there’s not only a historical law of mutual conflict, but maybe also a historical law of mutual aid and solidarity. One mainspring of my political activity seems to be making this law a reality so that people can really live with one another as brothers and sisters. Gaus: You study at the university in West Berlin. What has disgusted you the most about the conditions in Berlin and in the Federal Republic? Dutschke: Yes… maybe it’s the inability of the parties to show me something I’d find attractive. By that I mean something that relates to me, something that engages me. But that’s the sick thing about our parties. They can’t lay bare the interests and needs of party members, let alone those of the members of society at large. To work together in relating to people, engaging with them… Gaus: In all honesty, now you’re just complaining about the lack of a social utopia. Dutschke: Yes – I do understand that. Not just social utopia, but rather the inability of the parties to use that which they call politics to work out something that affects the people. Why are election rallies so boring? Why are there elections that differ in no way from the elections at Stalinist party conventions? Why is there an aspect of elections that amounts to nothing more than: “Yeah, that’s just an event one attends on a certain day…” It’s meaningless for the individual person because he knows that this election does not decide the fate of the nation. He has already agreed to this swindle, to be sure, but he knows that it’s fundamentally a swindle. Gaus: But one may grant that he’s alive after being overburdened for such a long time. Dutschke: He hasn’t been overburdened. Gaus: I would say that he was overburdened in a terrible way until 1945. Dutschke: We can even name the reasons why the parties of the 20s and 30s failed, the SPD and the KPD. We can say why it was possible for the NSDAP to steer the masses in the direction of fascism and to develop the germ forms of anti-capitalism into fascism, which is the culmination of anti-Semitic perversion. We can explain that… Gaus: As a result of a thoroughly-ideologized politics. And what concerns me with your desires is their ideological basis. Dutschke: No, not an ideologized politics, but certain principles of political activity. Not the development of the autonomous activity of the masses, but rather the Führer principle and the terroristic pressure imposed on all people. Those were the key components of fascistic action. But these are the key components for our group: autonomous action[20], self-organization, developing the people’s initiative and awareness, not having a Führer principle… Gaus: We agree that you’re speaking of your intentions… Dutschke: And of what may already be visible in rudimentary ways. Gaus: … whether they will be realized, only time will tell. How big is your following in West Berlin and in the Federal Republic? Dutschke: In West Berlin, we have about 15 to 20 people who are really working hard. That doesn’t mean that they’re career politicians, but they are devoting all their time, activity, and studies to this work of raising awareness. Gaus: Something about that is blatantly unjust. You say that these 15 people are devoting all their labor to political education, and I have a lot of respect for that. You say that this is a requirement for your movement. But then you say that they aren’t career politicians. That’s unfair to career politicians. Dutschke: Yes, but we have known for centuries what career politicians have done… Gaus: How do career politicians differ from these 15 people, of whom Rudi Dutschke is a member? Could you name a prime example? Dutschke: When you talk about the career politician as an ideal type – say, for example, a Kennedy or a Rathenau or whoever else – those are people whose material and financial basis, their material reproduction, etc. have been absolutely secured for their entire lives thanks to family tradition. Gaus: You can’t say the same for Erich Mende.[21] Dutschke: I didn’t mention him. Gaus: But he was a career politician. Dutschke: He was a career politician. But all these career politicians, especially someone like Mende, are characterized precisely by never having attempted to combine the concept of career politics with the concept of historical truth and the need to always tell their constituents where they stand. What is actually going on, what can be improved… Gaus: I think Mende would dispute that. Dutschke: I think so, too. Gaus: So, how big is your following beyond those 15 people? Dutschke: You see, we have about 150 to 200 active members. An interesting comparison might be made with the Black Power Movement in America. They have 90 members who are highly committed and maybe 300 to 400 active members. When we’re talking about these relative numbers – 15, 150, 300 members in West Berlin – since the SDS doesn’t constitute the movement, we could maybe say that the most conscious part of our movement consists of four to five thousand truly engaged university students who take part in educational events and campaigns, who are ready to face consequences for participating. Gaus: How many people in the Federal Republic could you bring out onto the streets for a demonstration against Vietnam, against America’s policies on Vietnam… Dutschke: We aren’t a Leninist cadre party. We’re a completely decentralized organization, and that’s a big advantage, but that also means that I can’t say who we’d be able to mobilize across the Federal Republic from today to tomorrow. I can only say that it happens very quickly for us because we’re decentralized and are always able to set the movement into motion. People are always ready to participate, and we don’t need to coerce them. It’s a voluntary matter. Gaus: You need a longer start-up time; you need to win people over. Once you’ve won them over, how many people can you get out onto the streets? Dutschke: In West Berlin, we can get about five to six thousand people onto the streets overnight. Now, what party in the Federal Republic can count on four to five thousand conscious people? Wouldn’t that be interesting… Gaus: Who’s financing you? Where do you and your friends get the money for your campaigns? Dutschke: Of course, there’s always the suggestion from places like the Springer Press that our people are somehow financed by the East.[22] Gaus: I didn’t say that. Am I allowed to mention that explicitly? Dutschke: Yes, you do need to mention it. This prejudice is passed along from the top down again and again, and I think it’s absolutely untenable. We reproduce our finances by our own effort. We have membership dues, and we receive donations from liberals and leftists who feel somewhat alone within the party apparatus, those who are afraid and feel guilty, reinsurers, people who are sympathetic to our cause. They all give us donations. That’s how we’re able to keep our heads above water. Look at the difference compared to career politicians – we have recourse to that which is fundamentally our own. These people are ready to participate. Gaus: Has Augstein ever donated?[23] Dutschke: Augstein has certainly donated. Gaus: I’ve heard that you don’t want to establish a party for the 1969 elections; you don’t want to participate as a party. What do you plan to do during those elections? Dutschke: If we’re still allowed to do anything at that point – there’s no guarantee that things will stay the same by then – we’ll try to use the elections to show that nothing will change in this country through voting. Our activities during the elections should give us the possibility of expanding our base through awareness processes and actions, and we will not transfer this potential to existing institutions but to our own institutions, our political clubs, our small, tentative approaches to self-organization. We will try to direct it there and maybe create something like a subculture, a counter-milieu, and that should involve creating a total state of cohesion where people are able to live better. This even includes doing certain things as a group, having our own facilities, whether those are cinemas or other establishments. There we will meet one another, educate one another; there we will get to know young workers in both the professions and the trades, and we will have political discussions and prepare for future campaigns. That is our path, and it goes on outside of the existing institutions. Gaus: Allow me to ask one last question, Mr. Dutschke. Would you be willing to provoke the established powers of the Federal Republic to such an extent that you’d be put in jail? Dutschke: I’ve already been to jail, and no one in our group is afraid of that possibility. It doesn’t mean much anymore when we’re apprehended during demonstrations, charged, and put in jail. The next day, there are always 100, 200, 300, maybe even more confessions from other friends who were also participating. That way, the individual never feels isolated as an individual. It’s not the way it was in the past, where someone could be held captive by the bureaucracy, by the executive authority of the state, and then be broken down. We’re no longer afraid to accept the possibility of imprisonment. There’s no alternative for us in our fight; imprisonment is simply part and parcel of it all. If it has to be that way, we’ll accept it, but it won’t stop us from continuing our fight. Notes [1] Original broadcast of “Zu Protokoll” can be found here: https://youtu.be/SeIsyuoNfOg [2] Sentence fragments rephrased for clarity. [3] The Wirtschaftswunder – an economic boom in West Germany that began during the reconstruction era of the 1950s. Dutschke uses the term facetiously. [4] Ellipses indicate pauses and interruptions in the original interview transcript. Gaus’s characteristic interview style is conversational, allowing for false starts and incomplete formulations. This translation attempts to convey the original meaning of Dutschke’s statements, though some of them have been rephrased for clarity. [5] The Socialist German Student Union, not to be confused with Students for a Democratic Society (US). The German SDS was formerly associated with the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) before it became an independent extraparliamentary organization in 1961. [6] The German Unmündigkeit here suggests that the people are considered incapable of making independent, adult decisions (mündig sein). Dutschke seems to imply that the public is being treated as children. [7] Herbert Marcuse agreed with Dutschke’s notion of a “long march through the institutions.” By this point, he was already considered the patron philosopher of the German and American student movements. Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man (1964) was widely read throughout the 1960s. [8] The National Democratic Party of Germany, a neo-Nazi party formed in 1964. The prevailing order Dutschke speaks of is an unchallenged grand coalition (große Koalition) consisting of the two largest parties: the CDU/CSU and the aforementioned SPD. At its height, the grand coalition controlled over 90% of the Bundestag. [9] The transcription of this sentence is somewhat ambiguous. However, Dutschke’s point is that a large portion of the world’s population is not compensated for its labor, which is exploited primarily by the countries belonging to NATO. [10] Dutschke critiques some features associated with the Soviet Union and its genesis, including vanguardism and socialism in one country. This is evident in his later remarks on Lenin. [11] Gaus is alluding to the Hegelian concept of sublation (Aufhebung). [12] In 1967, a right-wing military junta had already taken power in Greece at the time of this interview. [13] Erscheinungsformen in German. Dutschke is using a term found in Marx’s writing, where exchange-value is the “form of appearance” of something distinct from it. [14] In this context, the German Stahlbad is an idiom along the lines of a “baptism of fire.” [15] The Belgian village of Langemark was the site of early German gas attacks during World War I. The ensuing bloodbath was used as a patriotic fable in Nazi Germany and was the namesake for a Belgian division of the Waffen-SS. Gaus suggests a parallel between the reactionaries and Dutschke’s group. [16] A reference to Che Guevara’s “Message to the Tricontinental.” [17] The Greek junta received support from the US following the precedent of the Truman Doctrine. [18] Dutschke is most likely referring to Camilo Torres, who was killed in combat a year before this interview. [19] Dutschke’s theological positions are somewhat ambiguous. According to his diaries, he seems to have believed in the resurrection of Christ, but here he is primarily interested in the social and historical dimension of Christ’s ministry as a prototype for the revolution. See also: Dutschke, Rudi. Die Tagebücher: 1963-1979. Edited by Gretchen Dutschke, Kiepenheuer & Witsch GmbH, 2015. [20] Rosa Luxemburg’s concept of spontaneism had a strong influence on Dutschke. [21] Former Vice Chancellor of West Germany and leader of the laissez-faire Free Democratic Party during most of the 1960s. Mende was also a former soldier. [22] This is a tongue-in-cheek statement. At the time, the Springer Press was a conservative publication critical of the student movement at large. [23] Rudolf Augstein, founder of the magazine Der Spiegel. Translated with comments from:Vince K is a Minnesota-based PhD student whose research interests include urban studies, social control, surveillance, and theories of alienation. Outside of academia, he has seven years of experience as a professional translator in various countries. Archives October 2021

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed