|

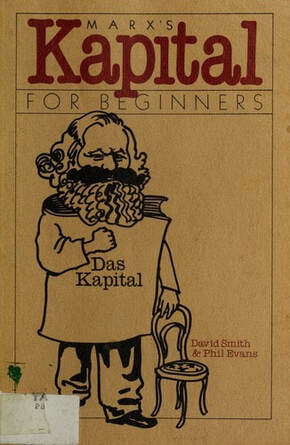

5/8/2021 The Minutiae and Microscopic Anatomies of Capital: Examining Marx’s Commodity Form. By: Calla WinchellRead NowIn Marx’s ambitious work Capital: Critique of Political Economy he has a daunting goal: to describe the functioning of capitalism that corrects the blindness of the preceding political economists that he had encountered. He seeks to denaturalize capitalism and to demonstrate the exploitative nature of its very foundations. This chapter epitomizes the method used throughout the text, which Marx builds on the back of the concept of the commodity form. Using the most quotidian concepts, like commodity and then the money equivalent, Marx makes the seemingly familiar feel mysterious through his “microscopic” gaze (Marx 90)[1]. Furthermore, through this scientific methodology, Marx reveals the strange homogenizing urge of capitalism, where everything is made equivalent through the money form. For example, where labor, previous to capitalism, was understood by its particular characteristics —what type of labor? What product? — under capitalism it becomes understood as an average “congealed” form of labor, with no particularities. Tracking capitalism’s impulse to make uniform provides a trail that Marx tracks, from the commodity form all the way to the “fetishism of commodity”. Capitalism, like the systems that came before it, lays claim to its own naturalness as proof of its necessity and inevitability. Seeking to problematize that viewpoint, Marx seeks to make the seemingly natural and unexamined aspects of capitalism alien. This reexamination, from a distance, of the foundational concepts of capitalism begins with the very smallest constitutive element: the commodity form. Marx acknowledges that, “the analysis of these forms seems to turn upon minutiae. It does in fact deal with minutiae, but they are of the same order as those dealt with in microscopic anatomy” (Marx 90). Though it “seems” to be minute, the commodity form is the heart of Marx’s labor theory of value, which posits that value is generated, not in the sphere of exchange, but in the sphere of production, when labor is performed. Marx adopts a scientific mode of inquiry, rather than an outrightly polemical or didactic mode. This choice manifests in many ways, from the metaphors he uses to more methodological questions of organization. He sketches out his view of capitalism as a living organism in his preface to the first German edition of Capital, saying that political economists had studied capitalism as one might an animal. “The value-form, whose fully developed shape is the money-form, is very elementary and simple. Nevertheless, the human mind has for more than 2,000 years sought in vain to get to the bottom of it all, whilst on the other hand, to the successful analysis of much more composite and complex forms, there has been at least an approximation” (Marx 89-90). In contrast, Marx seeks to describe the cellular level of capitalism. More importantly still, he seeks to prove that it is not the commodity that is “the economic cell-form” but rather value derived from labor. Turning his microscope to the commodity form, Marx argues that the commodity form is only an advent of capitalism. In order to be a commodity, an article must have “use-value” and “exchange-value”. The former essentially means that the object in question has utility that is separate and beyond its ability to be exchanged. While use-value is transhistorical, because objects have had utility since humans began using tools, the latter is contingent upon the advent of capitalism. Exchange-value means that one object can be exchanged for a certain quantity of another; the two object-types being exchanged need not be equivalent in quality and indeed, they rarely are. When viewed only as a bearer of exchange-value, the particular utility of an object is not considered. The exchange of two qualitatively different items is made possible because they share one common property: “that of being products of labor” (MER 305). This shared fact of being products of labor presumes that this labor is qualitatively the same, even though the true production process might require very different methods —spinning yarn versus carving wood, for example— and thus appear to be quite different. However, in the logic of capital, there is an abstract form of labor, what Marx terms a “congelation of homogeneous human labor” (MER 305). Essentially, this means that labor is quantified with the “socially necessary” time needed to produce something “under normal conditions” and “with the average degree of skill” (MER 305). Thus, value is a result of the labor-power expended on average, by an unskilled laborer, to produce the commodity in question. Simply put, commodity is best understood as value embodied. For example, the ingredients of a cake —sugar, flour, milk— lack as much value as the fully baked cake itself. Since the necessary components are purchased either way, the difference must be understood to be in the labor performed by the baker upon the materials which produced the higher value cake, as opposed to the unacted upon (un-labored) ingredients alone. In order for an object to have value —and so become a commodity— it must possess a use-value and an exchange-value. If it lacks the first, then the object will not be purchased, no matter the hours of labor spent producing it. Lacking the second would mean that no labor had gone into producing it, though it can still have a use-value. Marx’s specific term for such an object is “the spontaneous products of nature” like sunshine or wind, which qualify as something with use-value but that cannot be exchanged precisely because no labor-power has been expended on it. Where use-value relies on the qualitative, meaning it depends on the specificity of the object’s particular utility, exchange-value is the reverse. This means that value is “totally independent of [its] use-value” (MER 305). This dichotomy between the particularity of transhistorical use-value and the homogeneity of exchange-value plays out again and again in Marx’s account, exposing capital’s desire for exchange of uniform equivalents more generally. After detailing the components of the general commodity form, Marx proceeds to talk about the specific commodity form of labor-power. Marx distinguishes between the production of goods in previous eras from the production of goods under capitalism, pointing to the division of labor as a key difference. Citing textiles—a common example for Marx— as an instance of change in history, Marx writes “wherever the want of clothing forced them to it, the human race made clothes for thousands of years, without a single man becoming a tailor” (MER 309). Without a sphere of exchange such division would be highly impractical. Yet, for all the dividing of labor into specializations that capitalism necessitates, there is presumed to be an abstracted idea of the average worker’s ability to perform relatively unskilled labor. This more general concept of labor might seem to undermine Marx’s claim about the division of labor’s importance, but it instead serves to highlight the lack of true “specialization”; any human can perform the kind of tasks that Marx’s labor theory of value rests upon. This sense of labor as homogenous is not, however, able to be translated across societies. Marx makes it quite clear that abstract labor can only be abstracted for current societal contexts; it cannot be translated across borders or eras. In other words, the abstract labor of a farmer in the 17th century will not be the same abstracted labor for contemporary workers, and so it should not be applied universally. The “special form” of the commodity of labor-power is distinct because in its consumption, more value is generated (MER 310). The essential nature of the general commodity is one of consumption. Purchasing something gives access to the use-value of the object, which is used and then used up. In this normal paradigm, the object is depleted of value through use. In contrast to this general commodity form, the commodity of labor-power generates more value as it is used, for the laborer generates new value through their labor. So, the use-value of labor-power is its potential to generate still yet more value. This quality is what supports the labor theory of value. While abstract labor is simply what the average person can be expected to produce over a duration of time, how might one account for more skilled labor under this theory of value? Marx writes that this should be understood as “simple labor intensified” or “multiplied simple labor”. So, one hour of skilled labor might be equal to three unskilled labor hours. Given that these are made equivalent, Marx argues that all labor in his system should be understood as unskilled, “to save ourselves the trouble of making the reduction” (MER 311). Once again, the desire for standardization and uniformity of capitalism stands in contrast with the particularities of different labor. Marx has set out in the section to give an account first of the commodity form, as an essential building block of capital. After he describes this basic structure, he moves to the more particular question of a universal equivalent commodity. The necessity of this universal equivalent commodity, namely a money form, is essential for the functioning of capitalism. In order to describe a universal equivalent, Marx describes first how two commodities can be made to relate to each, so that one commodity expresses itself as the equivalent of another, different commodity. Marx writes, “the relative form and the equivalent form are two intimately connected, mutually dependent and inseparable elements of the expression of value; but, at the same time, are mutually exclusive, antagonistic extremes” (MER 314). In order to form a relationship between two commodities it is necessary to make one relational to the other, translating its value into another form. This second commodity simply expresses the first, but cannot express beyond that. In other words, there can only be one “unit” or one commodity which expresses itself and the other, relational commodity as well. The first commodity, which Marx terms “the relative form”, is embodied in the second chosen commodity. To return to the baking metaphor, we’ll assume that three bags of flour is the equivalent value of one cake. Cake is here the equivalent, and flour is the relative. This relational form points to the “special form” of labor as a creator of value. It is the cake and the flour’s state as products of labor that allow for their equivalence. It is a creation of equivalence that, “brings into relief the specific character of value-creating labour, and this it does by actually reducing the different varieties of labour embodied in the different kinds of commodities to their common quality of human labour in the abstract” (MER 316). One only needs to take this relational comparison a bit farther to arrive at a universal equivalent. In the previous example, cake is fitted to the role of universal equivalent, but a true money-form allows for easier still expression of relations of value-created-by-labor. The money form becomes the only equivalent, achieving “a directly social form” because it allows for relations of meaning to form between commodities and this new equivalent (Marx 161). However, the larger sociality of relation between laborers is further obscured. The homogenizing impulse that Marx has revealed with his comparisons between use-value and exchange-value, concrete labor and abstract labor, gains full expression with the mysteriously mute fetishism of commodity. All relationship between laborers is disappeared behind the gleam of the universal equivalent; meaning is displaced from its proper understanding of the sociality of labor, onto the abstracted universal equivalent commodity, the money form, which he discusses in the next chapter. It is a commodity, because it is value embodied —and thus, labor embodied— and because it has use-value, in that it allows for easy exchange between products, thus able to “satisfy the manifold wants of the individual producer” (MER 322). This ease of exchange directly obscures the “peculiar social character of the labor that produces” this fetishism of commodity (MER 321). Though, as Marx observes, “a commodity appears, at first sight, a very trivial thing, and easily understood”, through tracing the origin of the value derived from commodity to the expenditure of labor-power, Marx reveals the essentially unnatural and mysterious nature of the building block of capitalism: the commodity form. Examined under his “microscopic” view, the familiar is made alien to us, and capital can begin to be “de-naturalized”. [1] I used two editions of this chapter, as the Marx-Engels Reader seems to have abridged some sections. I will cite the Reader using the acronym “MER”. All other citations refer to the translated version of the whole text. See Work Cited for details. Citations Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. The Marx-Engels Reader. Ed. Robert C. Tucker. 2nd ed. New York: Norton, 1978. Print. Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Trans. Ben Fowkes. London, UK: Penguin, 1992. Print. AuthorCalla Winchell is trained as a writer, researcher and a reader having earned a BA in English from Johns Hopkins University and her Masters of Humanities from the University of Chicago. She currently lives in Denver on Arapahoe land. She is a committed Marxist with a deep interest in disability and racial justice, philosophy, literature and art.

1 Comment

“Well, Karl, what do you know about the Legalists and Han Fei in particular?” “I remember what Reese [“Dictionary of Philosophy and Religion” by William L. Reese] says. That he lived in the Third Century B.C., that he was the Prince of Han and committed suicide in 233 B.C. because the King of Qin wouldn’t accept his services. He is the major philosopher in the Legalist School.” “Pretty good. Chan calls this school the most radical of the schools for its rejection of Confucianism (morality) and Moism (religion). Remember, the Qin Kingdom conquered the other Chinese Kingdoms and the Qin Dynasty (221-206 B.C.) set up the imperial system, under the First Emperor, that ruled China until 1912. The dubious claim to fame of the Legalists is that they helped set up the ideological framework for the Qin. Han Fei was the most important of a line of Legalist philosophers. He also studied under Xunzi and, unjustly I think, some of his more ‘totalitarian’ tendencies have been read back into his teacher. Legalist predecessors were Kuan Chung (Seventh Century B.C.), Lord Shang, Prime Minister of Qin (Fourth Century B.C.), his contemporary, the Prime Minister of Han, Shen Buhai and Shen Dao (c.350-275 B.C.). Chan notes that his fellow student with Xunzi, Li Si, who died in 208 B.C. was behind the suicide of Han Fei. I can’t believe he killed himself just because he couldn’t get a job with the future First Emperor!” “That does seem strange. Here is some more info in Creel [H.G. Creel “Confucius and the Chinese Way”]. It seems Li Si actually turned the King against Han Fei by telling him that he would not support Qin in a war against Han. Han Fei was tossed into prison and forced to kill himself by Li Si. That makes more sense.” “It also makes Li Si a fake sage! That type of behavior seems completely against all the teachings of the philosophers we have so far discussed! Xunzi would not have liked that at all. Why did he do it?” “His motive makes it even worse. He knew that Han Fei was a better philosopher than he, and he was jealous that the King would prefer him. Li Si was already a minister in Qin when Han Fei came to offer his services.” “So, are we ready to look at the “Han Feizi” and see what this new philosophy was all about?” “I’m ready, Fred.” “Chan says Han Fei is most famous for his synthesis of Legalist views and for his discussion of the Dao which influenced all the Daoists of note. I will begin with Chan’s first selection ‘1. The Synthesis of Legalistic Doctrine.’ Han Fei starts by noting that Confucianism and Moism are the most popular philosophies and attacks them for trying to pretend they represent the wisdom of the old sage kings. Han Fei is against using the past as a model for the present and future. He says, since no one can really tell what the old sage-kings' true teachings were or how to apply them today, then, ‘To be sure of anything without corroborating evidence is stupidity, and to base one’s argument on anything about which one cannot be sure is perjury. Therefore those who openly base their arguments on the authority of the ancient kings and who are dogmatically certain of Yao and Shun are men either of stupidity or perjury.’ “ “Technically, while Mo may have mentioned Yao and Shun, it was Wen and Tang and Wu and Yu that he appeals to most of the time in the Chan extracts. But in principle Han Fei’s argument is against both Mo and Confucius.” “This next quote shows that the Legalists were in favor of a government of laws and not of men! ‘Although there is a naturally straight arrow or a naturally round piece of wood [once in a hundred generations] which does not depend on any straightening or bending, the skilled workman does not value it. Why? Because it is not just one person who wishes to ride and not just one shot that the archer wishes to shoot [so bending and straightening of wood is needed as a skill-tr]. Similarly, the enlightened ruler does not value people who are naturally good and who do not depend on reward and punishment. Why? Because the laws of the state must not be neglected, and government is not for only one man. Therefore the ruler who has the technique does not follow the good that happens by chance but practices the way of necessity ....’ And Chan remarks, ‘In the necessity of straightening and bending, note the similarity to Xunzi. The theory of the originally evil nature of man is a basic assumption of the Legalists.” “I still say that Xunzi was not like the Legalists. I pointed this out at the start of our discussion on the Xunzi.” “And I said I agreed with you. You will be happy to know that Chan also agrees with you and not with Fung [Fung Yu-lan, “A Short History of Chinese Philosophy”] who holds that Han Fei based his doctrines on those of Xunzi.” “Well, I like that! Just what does old Chan have to say about this issue Fred?” “He says the bending and straightening in Xunzi meant education and the like, but Han Fei only relied on rewards and punishments. Chan said, ‘Xunzi had a firm faith in man’s moral reform but the Legalists have no such faith.’ And, he adds, ‘It is misleading, at least, to say, as Fung does, that Han Feizi based his doctrines on the teachings of Xunzi.’ This is because they ‘were utterly different in their attitudes toward man as a moral being.’” “I’ll buy that. So, let’s go on with some more of the ‘Han Feizi’.” “Sure. Han Feizi says the enlightened ruler needs four things to ensure his success. Namely, the ‘timeliness of the seasons,’ the support of the people, ‘skills and talents,’ and finally a position of power. He says, ‘Acting against the sentiment of the people, even Meng Pen and Xia Yu (famous men of great strength) could not make them exhaust their efforts. Therefore with timeliness of the seasons the grains will grow of themselves.’ In fact with all four conditions, then, ‘Like water flowing and like a boat floating, the ruler follows the course of Nature and enforces an infinite number of commands. Therefore he is called an enlightened ruler....’” “Sounds like Daoism.” “You couldn’t be more right Karl. Chan’s comment on that quote I just gave is, ‘Of all the ideas of the Legalists, perhaps the most philosophical is that of following Nature, which was derived from the Daoists.’ And, although he did not include it in his “Source Book”, Chan says that one of the chapters in the “Han Feizi” is a commentary on the thought of Laozi.” “That’s excellent. Does he get more specific about law?” “Try this. ‘The important thing for the ruler is either laws or statecraft. A law is that which is enacted into the statute books, kept in government offices, and proclaimed to the people. Statecraft is that which is harbored in the ruler’s own mind so as to fit all situations and control all ministers. Therefore for law there is nothing better than publicity, whereas in statecraft, secrecy is desired....’” “Sounds a little like Machiavelli.” “He goes on, ‘Ministers are afraid of execution and punishment but look upon congratulations and rewards as advantages. Therefore, if a ruler himself applies punishment and kindness, all ministers will fear his power and turn to the advantages.’” “Yes, I remember this. The ‘two handles’ of government--reward and punishment. Machiavelli says a prince is better off being feared than loved, and I see that Han Fei also goes in for the fear factor.” “Yes he does. A minister gets punished if he does something small after having said he would do something big, but also if he expects to do something small and it turns out to be big. Han Fei says, ‘It is not that the ruler is not pleased with the big accomplishments but he considers the failure of the big accomplishments to correspond to the words worse than the big accomplishments themselves. Therefore he is to be punished....’” “That certainly won’t encourage ministers to surpass themselves! That seems counter-productive. I understand being punished for big talk and little deeds, but if you set out to do only a little yet accomplish something big despite yourself, I think it is not wise for the ruler to punish you. Suppose you said you would delay the enemy while the ruler collects his forces and instead you are able to defeat the enemy. What is the sense of being punished?” “I agree with you Karl but that is the way Legalists play the game. Here is what Chan says about it. ‘Like practically all ancient Chinese schools, the Legalists emphasized the theory of the correspondence of names and actualities. But while the Confucianists stressed the ethical and social meaning of the theory and the Logicians stressed the logical aspect, the Legalists were interested in it primarily for the purpose of political control. With them the theory is neither ethical nor logical but a technique for regimentation.’” “Well that it is, but it will not really work in the interests of the ruler. In fact the Qin Legalist state fell apart shortly after the death of the First Emperor. Don’t forget that Han Fei had to commit suicide, a victim perhaps of his own Machiavellian position.” “Here is a big attack on the Confucianists.” “This should be good!” “This attack is also directed at Mozi so his doctrines were still around. ‘At present Confucianists and Moists all praise ancient kings for their universal love for the whole world, which means that they regarded the people as parents [regard their children].... Now, to hold that rulers and ministers act towards each other like father and son and consequently there will necessarily be orderly government, is to imply that there are no disorderly fathers or sons. According to human nature, none are more affectionate than parents who love all children, and yet not all children are necessarily orderly.’” “So here come the ‘two handles’.” “It seems to be the case Karl. Han Fei says that you have to have laws against the disorderly people in the state. He makes the point that ‘people are submissive to power and few of them can be influenced by the doctrines of righteousness.’” “That’s the case in empirical states that haven’t been designed to conform to Confucian ideals. Why should we limit ourselves to these kinds of state?” “Because that is being realistic. Look, Han Fei says, at what happened to Confucius in the real world. In the real world ‘Duke Ai of Lu was an inferior ruler. When he sat on the throne as the sovereign of the state, none within the borders of the state dared refuse to submit. For people are originally submissive to power and it is truly easy to subdue people with power. Therefore Confucius turned out to be a subordinate and Duke Ai, contrary to one’s expectation, became a ruler. Confucius was not influenced by Duke Ai’s righteousness; instead, he submitted to his power. Therefore on the basis of righteousness, Confucius would not submit to Duke Ai, but because of the manipulation of power, Confucius became a subordinate to him. Nowadays in trying to persuade rulers, scholars do not advocate the use of power which is sure to win, but say that if one is devoted to the practice of humanity and righteousness, one will become a true king.’” “Just the view of Plato as well as al-Farabi [872-950 A.D, great Islamic Aristotelian]. But you don’t have to tell me that Han Fei thinks that that is bunk.” “With a vengeance! It looks to me that he wouldn’t support any of the Confucian policies and would rather see a big military state--Sparta rather than Athens! He says, ‘The state supports scholars and knights-errant in times of peace, but when an emergency arises it has to use soldiers. Thus those who have been benefited by the government cannot be used by it and those used by it have not been benefited.’” “It does look like a professional army would fulfill his ideas. But, that type of army is parasitical in times of peace and it makes oppression by the government so much the easier. I presume his reference to ‘knights-errant’ is a swipe at the Moists.” “Here are some more of his ideas, ‘If in governmental measures one neglects ordinary affairs of the people and what even the simple folks can understand, but admires the doctrines of the highest wisdom, that would be contrary to the way of orderly government. Therefore subtle and unfathomable doctrines are no business of the people.... Therefore the way of the enlightened ruler is to unify all laws but not to seek for wisemen and firmly to adhere to statecraft but not to admire faithful persons. Thus laws will never fail and no officials will ever commit treachery or deception.’” “You know Fred, I don’t think that this is an either/or type of situation. I’m sure the Confucians would also agree that the people should not be left out of consideration. They always advocated education. That doesn’t mean that just because you have the elementary schools you have to abandon the university--which is what Han Fei seems to be saying. His emphasis on ‘statecraft’--the secret machinations of the ruler’s brain seems to conflict with his confidence in the ‘laws’ and introduces arbitrariness into the system. As for officials never committing treachery or deception--look what happened to him. Either Li Si, a Legalist himself, committed treachery or Han Fei was engaged in deception and the future First Emperor was right to imprison him. But the consensus is that Han Fei was innocent. Therefore he was the victim of ‘statecraft’ and in this instance the laws failed. I think it was this contradiction in his system that led to its untenability in the long run and why Confucianism, which is more balanced and nuanced, somewhat succeeded. I would also like to point out that his stress on the ‘common people’ is probably due to the influence of Daoism and this influence is also the reason he failed to integrate popular education and ‘the doctrines of the highest wisdom.’ For him these doctrines didn’t exist in the Confucian or Moist sense.” “I think you are right Karl. These next words have a real Daoist flavor. He says, ‘In regard to the words [of traveling scholars], rulers of today like their arguments but do not find out if they correspond to the facts. In regard to the application of these words to practice, they praise their fame but do not demand accomplishment. Therefore there are many in the world whose talks are devoted to argumentation and who are not thorough when it comes to practical utility.... In their deeds scholars struggle for eminence but there is nothing in them that is suitable for real accomplishment. Therefore wise scholars withdraw to caves and decline the offering of positions.’” “Very Daoist! Too bad Han Fei did not take his own advice. If he had gone to live in a cave somewhere instead of going off to take a position in Qin, and struggling for eminence with Li Si, he would not have ended up having to commit suicide.” “Here is the last quote from this section of Chan. ‘Therefore in the state of the enlightened ruler, there is no literature of books and records but the laws serve as the teaching. There are no sayings of ancient kings but the officials act as teachers. And there are no rash acts of the assassin; instead, courage will be demonstrated by those who decapitate the enemy [in battle]. Consequently, among the people within the borders of the state, whoever talks must follow the law, whoever acts must aim at accomplishment, and whoever shows courage must do so entirely in the army. Thus the state will be rich when at peace and the army will be strong when things happen.’” “Wow! This is no good. ‘No literature of books’--this will result in a violation of the Prime Directive as the only views available will be Legalist and thus authority rather than reason will end up ruling people’s minds.” “Chan says, ‘The advocation of prohibiting the propagation of private doctrines eventually led to the Burning of Books in 213 B.C. and in the periodic prohibitions of the propagation of personal doctrines throughout Chinese history.’” “Chan wrote that before the ‘Cultural Revolution’, which was neither ‘cultural’ nor a ‘revolution,’ we can see the bad effects of this doctrine are still alive. Not allowing ‘personal doctrines’ means only state sanctioned ‘truth’ is allowed, a sure condition for ending up as far away from being able to find ‘truth’ as you can imagine. I hate to seem critical of the Chinese government, especially as it has raised the Chinese people out of feudal despair and into the modern world, but they should heed Carl Sagan’s advice that ‘The cure for a fallacious argument is a better argument, not the suppression of ideas.’” I’m not singling out China. Every government in the world could do better in this respect.” “Well put Karl, but now I’m going to go over the other section that Chan has in his “Source Book”, namely Han Fei’s discussion of Daoism, which Chan calls ‘one of the most important.’ Chan calls this section ‘Interpretations of Dao.’ Are you ready for this?” “Ready!” “OK, here goes, ‘Dao is that by which all things become what they are. It is that with which all principles are commensurable. Principles are patterns (wen) according to which all things come into being, and Dao is the cause of their being. Therefore it is said that Dao puts things in order (li). Things have their respective principles and cannot interfere with each other, therefore principles are controlling factors in things. Everything has its own principle different from that of others, and Dao is commensurate with all of them [as one]. Consequently, everything has to go through the process of transformation. Since everything has to go through the process of transformation, it has no fixed mode of life. As it has no fixed mode of life, its life and death depend on the endowment of material force (qi) [by Dao]. Countless wisdom depends on it for consideration. And the rise and fall of all things is because of it. Heaven obtains it and therefore becomes high. The earth obtains it and therefore can hold everything....’” “He seems to be following Laozi fairly closely.” “Yes indeed, as the following shows as well. ‘Whatever people use for imagining the real [as the skeleton to image the elephant] is called form (xiang). Although Dao cannot be heard or seen, the sage decides and sees its features on the basis of its effects. Therefore it is called [in the ‘Laozi ] “shape without shape and form without objects.”’” “Sort of like ‘Gravity” with Newton. It couldn’t be seen or heard but the effects, as with the falling apple, led Newton to work out its features. The great law that controls everything, like Gravity, that is the Dao.” “Han Fei goes on. ‘In all cases principle is that which distinguishes the square from the round, the short from the long, the course from the refined, and the hard from the brittle. Consequently, it is only after principles become definite that Dao can be realized.’” “But Dao is the basis of principle! To keep my Newton analogy going, I would have to say that it is only when objects are manifesting their attraction that Gravity can be realized.” “It is the ‘eternal’ Dao that Han Fei is interested in. He says, ‘Only that which exists from the very beginning of the universe and neither dies nor declines until heaven and earth disintegrate can be called eternal. What is eternal has neither change nor any definite particular principle itself. Since it has no definite particular principle itself, it is not bound in any particular locality. This is why [it is said in the ‘Laozi’] that it cannot be told. The sage sees its profound vacuity (xu) and utilizes its operation everywhere. He is forced to give it the name Dao. Only then can it be talked about. Therefore it is said, “The Dao that can be told of is not the eternal Dao.”’” “Does Chan say why this is ‘most important’?” “Yes he does. He goes into this passage with a long comment. ‘This is one of the earliest and most important discussions of Dao. It is of great importance for two reasons. First, principle (li) has been the central concept in Chinese philosophy for the last eight hundred years, and Han Fei was one of the earliest to employ the concept. Secondly, to him Dao is not an undifferentiated continuum in which all distinctions disappear. On the contrary, Dao is the very reason why things are specific and determinate. This is a radical advance and anticipated the growth of Neo-Daoism along this direction in the third and fourth centuries A.D.’” “That completes our treatment of Han Fei?” “It does. You know, I think we need to discuss Laozi and Daoism as this philosophy is almost equal to Confucianism in Chinese thought. If we want to really understand China today then we must understand the ‘Dao’ of Chinese Communism so we should get a grip on the thought of Laozi. O.K., let’s do it next. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. 4/30/2021 Antonio Gramsci and Political Praxis in the Materialist Theory of History. By: Sebastián LeónRead NowIn commemoration of the 84th anniversary of his death. Antonio Gramsci is one of the most relevant theorists in the history of Marxism - he is also one of the most misunderstood. Self-proclaimed heterodox leftists of all latitudes have made “neogramcism” their banner, finding in the Sardinian revolutionary a symbol of the break with real socialism, Marxism-Leninism and the materialist theory of history. Perhaps the best known figure in this intellectual trend has been the Argentine Ernesto Laclau, who once again made a key concept such as hegemony fashionable in the academic mainstream. Laclau defined his neogramscism as "post-Marxist", having completely abandoned historical and dialectical materialism, and conceived of social reality as a fundamentally discursive, unstable and radically contingent construct, in which the different forces dissatisfied with the present social arrangement could, through the elaboration of highly porous ideas and slogans, join a political force capable of challenging the common sense of society to the powers that be (that is, hegemony). Here, the conquest of socialism and communism gave way to a "radical democracy", in which every area of social life was left open to democratic deliberation to reconfigure the established order. It is necessary to differentiate Laclau, as well as other self-proclaimed “neo-Gramscians” and followers of Gramsci (whether they are “post-Marxists” or “heterodox Marxists”), from the man himself. For, although there are many who seek to decouple Gramsci and his thought from Marxism-Leninism, his effort cannot be understood if it is not as the attempt of a communist, committed to the revolutionary spirit of the October Revolution, to bring Marxist theory to life in territories that had previously remained unexplored. For, if the Bolshevik triumph had captured the imagination and hopes of Gramsci and a whole generation of Western revolutionaries, the reality of post-World War I Europe forced them to confront failure and the rise of reaction. Gramsci the Bolshevik One of the things that is fascinated about Gramsci is the extent to which he emphasizes the role of subjectivity and political will over the relentless inertia of the relations of production and the productive forces. There are those who think that the construction of socialism and emancipation has more to do with the will of human beings than with the creation of certain material conditions that make it possible; however, one must understand the weight that Gramsci gives to the subjective dimension of politics in its context. The Bolshevik triumph in Russia represented for him “the rebellion against Marx’s Capital ”, insofar as it embodied the triumph of a Marxism (that of Lenin) that came to be understood fundamentally as“ concrete analysis of the concrete situation ”with a view to the strategic organization of political action, over the positivist orthodoxy of the Second International, which clung to a linear and evolutionary model of history, in which the backward countries had to largely imitate the history of the West (necessarily having to go through industrial capitalism and the formation of liberal democracy before attempt a socialist revolution) before making their own. The Social Democrats of the Second International would place their hands on their head with the events in Russia, where the popular masses - mostly peasants - carried out the first successful socialist revolution of the 20th century. These events would profoundly mark a socialist like Gramsci, whose homeland was part of the southern periphery of Europe. However, none of this implied a voluntaristic understanding of politics: on the contrary, the Italian communist understood perfectly that the possibility of the Russians to create a socialist society was anchored in the availability of advanced technical-scientific resources in other parts of the world, which could be implemented by the communists to develop their productive forces without handing over the reins of government to the bourgeoisie. The emphasis on revolutionary organization and will did not imply a disregard for the objective conditions that constrained them; on the contrary, the consideration of these conditions should give rise to a form of collective action that found in the present an opportunity to make history, without applying abstract schemes alien to the singularity of the context. If Gramsci emphasized the weight of human agency, it was always from the coordinates of Leninism, which he saw as a truly dialectical materialism, which marked a distance with a mechanistic materialism, as harmful to revolutionary theory as voluntary idealism. Civil society, hegemony and historical bloc However, the context that the Italian Communists would have to face would be very different from the Russian one. With the rise of fascism, Gramsci, who had become head of the CPI and had been elected deputy, would be put in prison, and would remain there practically until the end of his short life. It would be there where he would elaborate the bulk of his theoretical writings, gathered in the famous volume known as The Prison Notebooks. In his writings from this stage of his life, Gramsci touches on a host of highly relevant topics, from history and economics to politics and philosophy, passing through education and culture. However, if there is an axis that articulates this scattered compendium, this will be the problem of the defeat of socialism in Europe (in particular, in Italy): why had the winds of change coming from the East finished evaporating? And why had the bourgeois reaction managed to take hold where socialism and the working class had failed? It is from this fundamental concern that Gramsci's interest in the question of hegemony arises. In his opinion, the dominance of the capitalist class over the whole of society could not be understood if it was reduced exclusively to a form of violent coercion (political or economic); rather, the power of it was to be thought of as an articulation of coercive force and persuasion. The first would correspond to what Gramsci called "political society": the strictly coercive apparatuses of the State, such as the legal apparatus, the armed forces, the police, etc. However, the second would correspond to “civil society”, which was rather the space of consensus and persuasion, where the beliefs, values and norms shared by the different members of a society were produced: the family environment, educational and religious institutions, the media, unions, etc. It was in the context of thinking about the formation of this sociocultural "common sense" that Gramsci recovered and expanded the Leninist concept of hegemony, which would come to refer to the political domain of a social class (the bourgeoisie), anchored in its pact with other social classes (such as the petty bourgeoisie) and their undisputed control of the cultural field, making common sense of their particular interests and worldview. From his point of view, it would have been this form of hegemonic control, and not its coercive power, that would have allowed the bourgeoisie to subdue the progressive forces of the continent and strengthen its dominance. It would be these theoretical elaborations that would lead Gramsci to take an interest in fields that Marxist theory had typically relegated to a more marginal place, such as the culture, tradition and faith of the popular classes. From his point of view, the Bolshevik triumph in Russia, as it had occurred in the context of war, had only been possible because the aristocratic and bourgeois elites had not managed to consolidate hegemony, and this allowed Lenin and the Bolsheviks to win in a war of maneuvers (basically, defeating them in an open confrontation in the period of the Russian Civil War). On the other hand, where the hegemony of the bourgeoisie and its allies was entrenched, the only way to seize political power and transform the relations of production was through the formation of a “historical bloc” of a “national-popular” character. With the proletariat at the head, an alliance of the popular or subaltern classes (poor and middle peasants, progressive layers of the petty bourgeoisie, and, in a context such as Latin America, the indigenous peoples) had to be formed which, united by a popular progressive culture, (through a new philosophy and a new morality, new artistic and literary expressions, and a new spirituality that articulates the experiences of the people in a key revolutionary manner) could be transformed into a counter-hegemonic force, ready to contest the bourgeois common sense of society in a "war of positions", intervening politically and finally fracturing capitalist control of the means of production. A good recent example of how the consolidation of this popular hegemony can not only win the ideological dispute to the bourgeoisie, but also guarantee the vitality of a revolutionary process, is the recent victory of the MAS in Bolivia after the coup against Evo Morales in 2019. Despite the tragic political defeat, the forces of reaction could not finish imposing themselves on Bolivian society, since the profound changes in the national culture carried out by the MAS during its years in power, had earned it the massive support of a heterogeneous but ideologically favorable people for their political project. For this reason, eventually the coup plotters had no choice but to stop postponing the elections and accept their defeat and the return to power of their enemies. Of course, the coup against Morales also leaves the lesson that a victory in the war of positions does not guarantee the uninterrupted continuity of the revolution. It is also necessary to be prepared to win in the war of maneuvers, to defend by arms the transformation of society when the reactionaries make it necessary. However, it is clear that the thought of Antonio Gramsci, far from implying a break with Marxism-Leninism, represents a crucial, truly dialectical development of the materialist theory of history, one that is of great importance for thinking about the context of contemporary bourgeois democracies. AuthorSebastián León is a philosophy teacher at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, where he received his MA in philosophy (2018). His main subject of interest is the history of modernity, understood as a series of cultural, economic, institutional and subjective processes, in which the impetus for emancipation and rational social organization are imbricated with new and sophisticated forms of power and social control. He is a socialist militant, and has collaborated with lectures and workshops for different grassroots organizations. Translated and Republished from Instituto Marx-Engels.

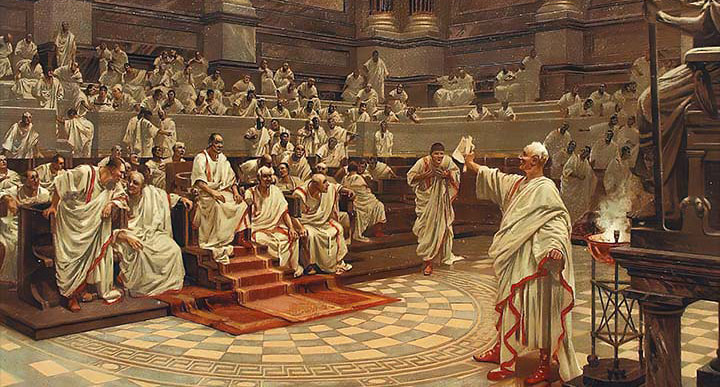

The three pillars of American republicanism“Bill of Rights Socialism” was first put forward by Gus Hall, Chairman of the Communist Party, USA, in his 1990 pamphlet The American Way to Bill of Rights Socialism. Emile Shaw wrote in 1996 that Bill of Rights Socialism “conveys the idea that we will incorporate U.S. traditions into the structure of socialism that the working class will create.” Since then, the CPUSA has continued to deepen and expand this theory to correspond with the real needs of struggle. The CPUSA is not alone in this project; other communist parties have also been applying Marxism-Leninism creatively to produce important innovations, bringing socialist construction into the modern age while also adapting their own path to their unique national conditions. How could it be otherwise? All struggles for socialism have unfolded within the context of their particular national circumstances. In Vietnam, it produced “Ho Chi Minh Thought.” In Cuba, the revolution linked itself to the legacy of Jose Martí. The many innovations in China are known as “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics.” No struggle has ever discounted their unique political traditions and general national conditions and been successful in achieving liberation. US republican traditions were deeply influenced by the Roman republic, where political sovereignty was derived from a free citizenry rather than a single monarch. According to Irish philosopher and world-renowned political theorist Philip Pettit, this centuries-old tradition of republicanism can be defined by “three core ideas” familiar to any US citizen: The first idea, unsurprisingly, is that the equal freedom of its citizens, in particular their freedom as non-domination — the freedom that goes with not having to live under the potentially harmful power of another — is the primary concern of the state or republic. The second is that if the republic is to secure the freedom of its citizens then it must satisfy a range of constitutional constraints associated broadly with the mixed constitution. And the third idea is that if the citizens are to keep the republic to its proper business then they had better have the collective and individual virtue to track and contest public policies and initiatives: the price of liberty, in the old republican adage, is eternal vigilance.1 These “three core ideas” form the bedrock of the political tradition of the U.S. republic. Bill of Rights Socialism, then, must grapple with these three core ideas if we are to synthesize the revolutionary struggle of the working class with the unique political conditions of the United States. Freedom and the republic The ideological core of the U.S. is its emphasis on the concept of “freedom.” Anyone with even a passing familiarity of U.S. politics knows that every single other question revolves around this core ideal. No other single concept, even that of democracy, holds as much power as this idea. Pettit distinguishes two approaches to freedom: liberalism and republicanism, both of which were present at the birth of the United States. Liberalism developed out of the European enlightenment period. It was a product of the rising bourgeoisie, which sought to guarantee freedom of commerce while leaving many other areas of domination untouched. Its basis is the freedom of the individual to own and dispose of property with a minimum of state interference. Republican freedom is rooted in the Roman idea that to be free, a person must not suffer dominatio. This means that a free person must be free not only of active interference of political power but also inactive, latent interference by any outside force. Freedom is not only an act, but a status. The real enemy of freedom in the republican tradition is not just interference by political authorities; it is the arbitrary power that some people may have over others.2 Pettit elaborates: “[Freedom] means that you must not be exposed to a power of interference on the part of any others, even if they happen to like you and do not exercise that power against you.”3 Specifically, this means you are not free if you have a good boss or a good landlord who has the power to arbitrarily intervene against your employment or housing, but simply chooses not to do so. If that power exists, even in a latent and unexercised way, working-class people cannot be understood to have the status of freedom, since this “freedom” may arbitrarily change at any given moment. Working people under capitalism live in day-to-day dependence on the employing class. Pettit articulates what he refers to as the “eyeball test” to help clarify what republican freedom means: [Citizens] can look others in the eye without reason for the fear or deference that a power of interference might inspire; they can walk tall and assume the public status, objective and subjective, of being equal in this regard with the best. . . . The satisfaction of the test would mean for each person that others were unable, in the received phrase, to interfere at will and with impunity in their affairs.4 This definition of freedom should be intuitively familiar to all working-class people. Are you free if you have to pretend to be friends with your boss, bite your tongue, or fake your laughter to stay on the boss’s good side? When at-will employment prevails in so many workplaces, can working-class people be free if they can be fired for any reason or no reason at all? According to the republican definition of freedom, the answer is unequivocal: Working people are not free under capitalism. Crucially, this means republicanism is distinct from the libertarian theory of freedom. Rather than being concerned exclusively with a vertical theory of freedom, where the state alone is seen as a threat to freedom, republicanism is also concerned with the arbitrary power private citizens can have over one another. Republican freedom means freedom not only from arbitrary state interference, but also from abusive partners, racial and national discrimination, and the private tyrannies of modern capitalism. Republican freedom has always meant more than just free markets. Bill of Rights Socialism, then, recognizes the inherent contradiction of “freedom” in monopoly capitalism — it is a smokescreen for the objective increase of unfreedom for the sake of profit. In today’s stage of capitalist development, the objective condition of most of U.S. society and the broader world is to be unfree and dominated by finance monopoly capitalism and imperialism. Second, Bill of Rights Socialism asserts that this contradiction can be resolved only by putting an end to the dictatorship of monopoly capital through a popular, democratic revolution that elevates the working class to the leading, decisive social element constituting state power. The mixed constitution as a class balancing act The second “core idea” of republicanism is the “range of constitutional constraints associated broadly with the mixed constitution.” This tradition of the “mixed constitution” (mixed government) developed out of revolutionary class struggle as a way to balance the contradiction between the general “human” struggle for emancipation and the particular class project upon which the new state must be founded. The most well-known republic in ancient history was formed in Rome with the overthrow of the Roman monarch Lucius Tarquinius Superbus by the patrician aristocracy of Rome. Tarquinius’ rule had become so intolerable to the aristocracy that they resolved by degrees to overthrow him. Yet the patricians by themselves could not bring to bear enough force to decisively win in their revolutionary struggle. The revolution was sparked when the masses of plebians rioted over the rape of Lucretius by Tarquinius’ son and her subsequent suicide. This mass activity was critical for the aristocracy to unite and banish the monarchy and replace it with two consuls who would be able to “check” one another through a veto. The mixed constitutions of republics emerged out of this historical process as the institutionalization of a balanced form of class rule. The Roman aristocracy was able to secure its position of power in the Roman Senate. Yet spontaneous plebian activity in the revolutionary struggle forced the patricians to integrate the popular class into its republican system as well. Checks and balances in a republic are reflections of the underlying balance of class forces at a particular moment when that republic is first constituted. Machiavelli makes this observation explicitly in his Discourses on Livy: I say that those who condemn the dissensions between the nobility and the people seem to me to be finding fault with what as a first course kept Rome free, and to be considering quarrels and the noise that resulted from these dissensions rather than the good effects they brought about, they are not considering that in every republic there are two opposed factions, that of the people and that of the rich, and that all laws made in favor of liberty result from their discord.5 According to political scientist Kent Brudney, Machiavelli “accepted the class basis of political life and believed that class conflict could be beneficial to a republic.” The “creative possibilities of class conflict” were recognized for “their importance to the maintenance of Roman liberty.” Brudney continues: “The episodes of conflict between the Roman patriciate and the Roman people were vital to the development of good laws and to the continuity of Rome’s founding principles.”6 This class-struggle understanding of mixed constitutionalism was also at the fore in the debates around the ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Scholar James Wallner directly connects the debates around the creation of the Senate with Machiavelli’s theory of institutionalized class struggle: The U.S. Senate exists for one overriding reason: to check the popularly elected U.S. House of Representatives. Throughout the summer of 1787, James Madison and his fellow delegates to the Federal Convention highlight, again and again, the Machiavellian observation that institutionalized conflict was essential to the preservation of the republic. Trying to inject an updated understanding of Machiavelli’s dictum into the heart of the new federal government, they created a Senate whose institutional features — size, membership-selection process, nature of representation, length of term of office, compensation — are properly understood only in relation to the body’s House checking role.7 Wallner points to Federalist Paper No. 62, where James Madison wrote: “The necessity of a senate is not less indicated by the propensity of all single and numerous assemblies to yield to the impulse of sudden and violent passions, and to be seduced by factious leaders into intemperate and pernicious resolutions.” The recent Shay’s Rebellion had been sparked by Massachusetts farmers demanding debt relief that was opposed by the merchant class that dominated the state government. This rebellion pressed the Federalist framers to consider the inclusion of an “aristocratic” senate capable of effectively subduing the “violent passions” of the masses, something missing from the Articles of Confederation that had preceded it.8 Thus, we see that “mixed constitutions” of republics are only the institutionalization of class struggle. If the republic is supposed to make the affairs of public power a question of public input, it must always balance the class foundation of the state with at least the nominal political participation of the masses. Ruling class power in a republic is always concentrated in the senate, and popular power is always located in a “lower” branch of government. This balance creates a dynamism between the two while also developing a hegemonic understanding of the state as representing “the whole people,” even if the state is always constituted under a specific class basis. Bill of Rights Socialism deepens the theory of the mixed constitution and gives it a proletarian character. Rather than calling for the abolition of the senate as such, Bill of Rights Socialism recognizes the need to reconstitute the republic along proletarian class lines, transforming the current senate founded on the “wisdom” of slave owners and oligarchs into an “industrial” senate that is instead based on the wisdom and experience of the leaders of the working class. Like Lenin’s soviets, the industrial senate would be built out of “the direct organisation of the working and exploited people themselves, which helps them to organise and administer their own state in every possible way.” Leaders, drawn from the broad working-class majority, would carry with them both an intimate knowledge of all parts of the production process and a distinct working-class perspective into the development of public policy. And like both the soviets and senates past, the industrial senate would be insulated from universal direct election, with a focus on cultivating tested working-class leadership collaborating to build and protect a common vision of a democratic socialist republic. The class character of the senate would serve as a “check” on one side of the equation.9 But Bill of Rights Socialism can grow only out of the success of a massive people’s front. Led by the organized working class, this front would also contain all progressive people and class allies, including small farmers, small- and medium-size-business owners, the self-employed, and independent intellectuals and professionals. The primary stage of socialism does not end class struggle but transforms it under the decisive political rule of the working class. A “People’s House” would provide a democratic space for these other class elements to make constructive and progressive contributions to building socialism without sacrificing or obscuring the working-class nature of the new republic. Further, experience from the last century indicates that even a working-class state can degenerate bureaucratically without broader popular participation and oversight. In addition to incorporating non-proletarian class elements constructively into the workers’ republic, the lower house would also provide a space for the exercise of universal suffrage and the direct election of representatives by the whole people. These popular representatives could play a consultative role to the industrial senate and provide institutional oversight. This would provide a “check” on the other side of the equation. The “checks and balances” between the industrial senate and the people’s house would capture the “quarrels and the noise” familiar to American democracy while preserving absolutely the republic’s fundamental class nature. This dynamic interrelationship creates the conditions for the third core idea of republicanism to prevail, the “contestatory citizenry.” It is right to rebel (within limits) The third core idea of republicanism depends on the active engagement of its citizens “to track and contest public policies and initiatives.” Freedom can be secured only through struggle. This ideal has been a fundamental political principle of all oppressed people struggling for their democratic rights and freedom in the United States. Frederick Douglass taught us years ago the price of freedom: If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet depreciate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.10 The contestatory citizenry forms a fundamental basis for the Bill of Rights and so must serve as a basis for Bill of Rights Socialism. These rights include freedom of speech, of assembly, of faith and conscience, and the right to be informed about the functioning of public power. Politically critical art, protests, and organizations must play a fundamental role in the construction of socialism in the United States and thus must be protected under Bill of Rights Socialism. Struggle does not only occur between oppressor and oppressed, between exploiter and exploited. Struggle also goes on within the oppressed and exploited. Historical development has created an unevenness within the working class: divisions around race, sex, sexuality, religion, cultural beliefs, nationality, language, and so on. This unevenness can be overcome only after a long period of struggle to resolve these divisions and build a unity through our diversity; to give real content to the national motto “E Pluribus Unum.” While the initial steps in this process of internal struggle for unity within the working class and democratic forces must be made before the establishment of socialism by building a people’s front, the establishment of socialism does not mechanically erase the social unevenness within that people’s front overnight. Revolution and reform are distinct, but also deeply interrelated. The development of social scientific methods and professional specialization has produced the historical capacity to carry out deep and broad reforms to the social system in a planned, scientific, and rational way. Reform can and must always go on, improving social institutions and making sure they advance with the times. However, reform does not happen abstractly, but according to the degree of political will brought to bear on the process. Reform in a social system hits a wall when the ruling class is no longer willing to exercise its political will to allow the reform process to deepen and expand according to the needs of the populace. Revolution is not in and of itself the solution to social problems; revolution is the punctuated transformation from one form of class rule to the next. This transformation in class rule does not replace reform, but unlocks it to unfold more deeply, at a faster pace, and in a more thoroughgoing way than the degenerate ruling class that was replaced could or would allow. By elevating the working class to the level of the ruling class in a workers’ republic, the struggle for reforms is not ended but transformed. Republicanism allows this reform struggle to take place both on an individual, contestatory foundation protected by a socialist Bill of Rights, as well as within the bounds of law constrained by socialist constitutional forms. Peace, prosperity, democracy, and freedomLet us be crystal clear: the United States needs a socialist revolution. The old ruling class, dominated by finance monopoly capital and incapable of keeping pace with the needs of the time, must be overthrown and in its place the working class, at the head of a mass democratic movement of all oppressed people and classes, must be elevated to rule in its place. The class basis of the current republic must not be ignored but instead placed at the center of the conversation. But the struggle is not to “abolish” the republican form outright. There are no serious ideas, to be perfectly frank, on what to put in its place. The soviet system was for the Soviets, the Chinese system for the Chinese, so on. The struggle is to revolutionize the republic to preserve the republican system at a higher level of development. Indeed, the fundamental argument of Bill of Rights Socialism must be that only a socialist revolution can preserve the republican liberties and democratic rights that so many oppressed and exploited people have fought hard and made tremendous sacrifices to secure. Socialist revolution means the deepening of democracy under the decisive state leadership of the working class. This essay is only a theoretical sketch to show the consistency between Marxism-Leninism and the “core ideas” of the republican political tradition. There are an almost limitless number of questions that arise from its premise: Can a workers’ republic be secured through the amendment process or through a new Constitutional Convention? How exactly should an industrial senate be ordered and secured? Should it be through indirect election, sortition (selection by lottery), selection, or a combination? How does federalism fit into this picture? How can we more explicitly articulate its relationship to imperialism and oppressed nations? And many more. Only through thoughtful struggle — not isolated contemplation or outrageous sloganeering — can the political soil be tilled to allow new possibilities to develop. Bill of Rights Socialism is not an “answer” in itself but a path to be blazed by combining the creative leadership of the Communist Party with the limitless dynamism and transformative potential of millions of Americans from all backgrounds linked together in the struggle for peace, prosperity, democracy, and republican freedom. Sources

AuthorBradley Crowder was born and raised in the Permian Basin oil patch that spans eastern New Mexico and west Texas. He is a labor organizer that has worked with the American Federation of Teachers and the Fight For 15. He has his undergraduate in economics from Texas State University and currently working on his master's degree in labor studies at UMass - Amherst. He is a proud member of the Communist Party, USA. Republished from CPUSA