|

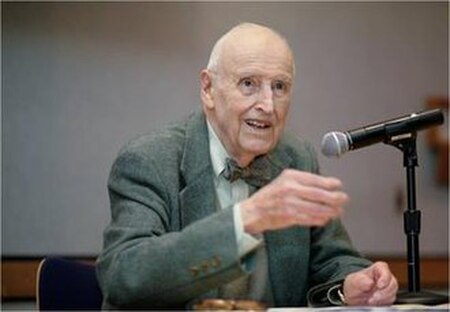

You might think the Ancient Egyptians too remote in time to be anything other than intellectual curiosities. Jan Assmann, the great German Egyptologist, thinks otherwise. Early on in his masterful reconstruction of the Egyptian mind set, he tells us that "ancient Egypt is an intellectual and spiritual world that is linked to our own by numerous strands of tradition." A brief review can only barely touch on the topics discussed in this book, but I will try to give some examples of Assmann’s conclusions with reference to our links to the Ancient Egyptians--they may be more extensive than you might think. Take for example the ancient work "The Admonitions of Ipuwer" from the thirteenth century B.C., (around the time of Ramesses II, c. 1303–1213 BC) which describes "the nobles" as "full of lament" and the "lowly full of joy." Bertolt Brecht was so impressed by this work that, Assmann says, "he worked part of it into the ‘Song of Chaos’ in his play ‘The Caucasian Chalk Circle.’" Ipuwer was lamenting the overthrow of established order by the lower classes-- so long has the specter of Communism been haunting the world (not just Europe) that Brecht could sense the presence of comrades over three thousand years ago! Brecht made a few slight changes, Assmann says, and the Egyptian sage’s lament became "a triumphal paean to the Revolution. A useful Egyptian concept to know is that of "ma’at" which Assmann defines as "connective justice" which "holds for Egyptian civilization in general." Basically "connective justice" is the idea that all actions are interconnected with those of others such that it "is the principle that forms individuals into communities and that gives their actions meaning and direction by ensuring that good is rewarded and evil punished." Assmann likens this concept to what he calls the "connection between memory and altruism." Looking at our own times, he says this Ancient Egyptian concept is manifested in the ideas of Karl Marx (and also in Nietzsche’s "Genealogy of Morals"). He quotes Marx who wrote that [Private] "Interest has no memory, for it thinks only of itself." This is a quote from issue 305 of the Rheinische Zeitung, Nov. 1, 1842 (not as cited by Assmann issue 298 Oct. 25, 1842). The point being that the State should look to the collective good of all citizens and not be used to further private or individual interests. It must have "memory" directed toward the general good. This is also the point of ma‘at. The Egyptian Middle Kingdom work "Tale of the Eloquent Peasant" makes this point. This implies that we could find basically "Marxist" social values being discussed in Egypt! As Assmann points out, "Ma‘at is the law liberating the weak from the oppression at the hands of the strong. The idea of liberation from the oppression caused by inequality is informed at least to a rudimentary extent by the idea of the equality of all human beings." It should be noted that the picture many have of ancient Egypt as a repressive slave state is the result of the Old Testament tradition. That tradition does not represent the actual state of affairs with respect to the functioning of the Egyptian state. An examination of the literary remains of the Egyptians themselves shows an entirely different society than that portrayed in Biblical propaganda. "The Egyptian state," Assmann writes, " is the implementation of a legal order that precludes the natural supremacy of the strong and opens up prospects for the weak (the ‘widows’ and ‘orphans’) that otherwise would not exist. Besides Biblical misrepresentations of Egyptian thought there were also the misunderstandings of the classical writers. For example, the Greek Diodorus, who left behind a description of the "Judgment of the Dead", presents the "facts" in contradiction to what we know is described in the Egyptian "Book of the Dead." In fact, Assmann avers that the Egyptian account is similar to the 25th Chapter of the "Gospel According to St. Matthew" where the reward of going to the "House of Osiris" is "replaced by the Kingdom of God." In fact, I think, many so-called Christian values and beliefs actually have their origin in Ancient Egyptian religious and ethical concepts. We should remember that the first "monotheist," after all, was the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten (r. cir. 1352-1338 B.C.) who stood "at the head of a lineage very different from his predecessors’, one represented after him by the Moses of legend, and later by Buddha, Jesus, and Mohammed," according to Assmann. As a truth seeker he also differs from the three aforementioned in that as "a thinker, Akhenaten stands at the head of a line of inquiry that was taken up seven hundred years later by the Milesian philosophers of nature [i.e., the Greeks] with their search for the one all-informing principle, and that ended with the universalist formulas of our own age as embodied in the physics of Einstein and Heisenberg." Assmann has a very high opinion of Akhenaten! Unlike earlier Egyptologists who think the ideas of Akhenaten were repressed by his successors (due to their--Akhenaten's ideas that is-- "deism" rather than "theism" characteristics), Assmann maintains that they were "elaborated further and integrated into" the religious teachings of the age of Ramesses and his successors. From here they eventually influenced Plato, and, since Plato was the basis of the thought of Augustine, Christianity. However, Christianity ended up the mortal foe of the Egyptian religion and ultimately destroyed it and the culture that produced it. Today we know more about the civilization of Ancient Egypt than has been known since its own time. We must come to grips with this new knowledge, and especially with the recovered literature of the Egyptians and "attempt" as Assmann says, "to enter into a dialogue with the newly readable messages of ancient Egyptian culture and thus to reestablish them as an integral part of our cultural memory." This ancient African civilization has more to offer us than the distortions of the Old Testament and Euro-Christianity (imposed on the Americas) present. This review has only skimmed the surface of this important book. I hope it inspires people to read the book itself. The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs by Jan Assmann (translated by Andrew Jenkins) New York, Metropolitan Books, 2002. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. Archives October 2021

1 Comment