|

10/4/2023 50 detained, over 100 homes raided in sweeping crackdown on press freedom in India. By: Zoe AlexandraRead NowThe homes of over 100 journalists, contractors, and former employees associated with the progressive news outlets Newsclick and Peoples Dispatch, as well as Tricontinental Research Services were raided by Indian authorities in the early morning of October 3 in the capital New Delhi. Several raids were also carried out in the cities of Noida, Ghaziabad, Gurgaon and Mumbai. According to local reports around 50 individuals were taken in to the police station for additional questioning. Newsclick editor-in-chief Prabir Purkayastha and administrator Amit Chakraborty have been arrested under the draconian anti-terror law, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). At least 500 police officers and intelligence agents participated in the operation. Among those who faced raids, interrogation, and detention are renowned journalists Urmilesh, Abhisar Sharma, Aunindyo Chakraborty, Bhasha Singh, Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, comedian Sanjay Rajoura, sports journalists Arjun Pandit, and human rights activist and former political prisoner Teesta Setalvad. Following his release Sharma said, “After a day long interrogation by Delhi special cell, I am back home. Each and every question posed will be answered. Nothing to fear. And I will keep questioning people in power and particularly those who are afraid of simple questions. Not backing down at any cost.” Democracy under attack Police records show that the case against Newsclick under UAPA was registered on August 17, just over a week after a New York Times report was published which alleged that Newsclick, amongst other progressive news outlets, is part of a Chinese news propaganda network. The report sparked a political and media scandal within India, which saw right-wing news outlets running dozens of pieces lodging baseless accusations that the members of the outlets are Chinese propagandists. Members of parliament from the far-right ruling Bharatiya Janata Party as well as high-level authorities like Home Minister Amit Shah also made similar statements on the parliament floor and to media. Today’s raids and mass repression have been widely condemned by progressive organizations, press associations, and opposition parties from across India as a grave attack on democracy, civil liberties, and human rights. The Editors Guild of India released a statement expressing deep concern “about the raids at the residences of senior journalists on the morning of October 3, and the subsequent detention of many of those journalists.” The guild is urging the Indian government “to follow due process, and not to make draconian criminal laws as tools for press intimidation.” The Delhi State Unit of All India Lawyers’ Union stated that they were “deeply concerned about the implications of these arrests for press freedom and the democratic values that our nation holds dear… Freedom of the press is a cornerstone of any vibrant democracy. It is essential for journalists to be able to report independently on matters of public interest without fear of harassment or intimidation. Journalists play a crucial role in holding those in power accountable and in informing the public about important issues.” The All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA) said in a public statement, “This highly undemocratic, unjustified, repressive action has been ostensibly been carried to intimidate independent and fearless journalists and others who have been critical of the government policies. The BJP government has now chosen to use the draconian UAPA along with other sections of the IPC to carry out these latest raids and confiscate the electronic belongings, including laptops and mobiles of the concerned individuals.” Witnesses report that the over 100 home raids lasted on average between four and 10 hours, and those interrogated faced a wide range of questions such as whether or not they had reported on the farmers protests in India, the protests against the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act, India’s mismanagement of COVID-19, or anything considered “anti-government”. In some cases, authorities ransacked people’s homes searching for material and one person reported that authorities threw his books to the floor and confiscated all titles by German philosopher Karl Marx. The cellphones and computers were seized from the majority of those who faced raids and were detained. The office of Newsclick in New Delhi was sealed by police after it was raided. The home of the Secretary General of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) Sitaram Yechury was also raided. Following the raid he told media, “Police came to my residence because one of my companions who lives with me there, his son, works for Newsclick. The police came to question him. They took his laptop and phone. What are they investigating? Nobody knows. If this is an attempt to try and muzzle the media, the country must know the reason behind this.” The repression today is just the latest act of harassment against Newsclick which was first raided in February 2021 by the Enforcement Directorate alleging economic fraud and money laundering. At the time, many activists had highlighted that the attack had occurred amid the growing farmers protests. Newsclick was one of the outlets providing consistent reporting on the struggle and had gained widespread notoriety for its on the ground reports from farmers’ protest camps. The country’s courts had granted the site protection from any “coercive measures” such as arrest and imprisonment by authorities in this case, but the latest UAPA case grants authorities special privileges to override those court protections. The UAPA which was first established in 1967 has come under increased scrutiny in recent years as it has been used by the government of far-right BJP leader Narendra Modi to persecute human rights activists, journalists, and scholars in the country. The law gives the government special powers to bypass civil liberties, fundamental rights and freedoms of citizens such as the right to a fair trial. The amendment to UAPA in 2008 gives the government the power to designate individuals or groups as terrorist with no formal judicial process. In a statement condemning the arrest of several anti-CAA protesters in 2020, Amnesty International wrote, “The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) is routinely used by the government to bypass human rights and stifle dissent. In 2018, the conviction rate under UAPA was 27% while 93% of the cases remained pending in the court. It is a mere tool of harassment that the government uses to harass, intimidate and imprison those who are critical of the government. The slow investigative processes and extremely stringent bail provisions under UAPA ensure that they are locked up for years altogether, creating a convenient setting for unlawful detention and torture.” The Students Federation of India (SFI) has called upon its units across India to organize emergency protests in response to “the brutal crackdown on Indian media by the Modi government.” Archives October 2023

0 Comments

On Monday, the Security Council of the United Nations (UN) authorized the deployment of Kenyan troops to Haiti. The intervention responds to a request issued by the acting prime minister and unelected head of Haiti, Ariel Henry, whose regime has been legitimized by support from the US, France, and Canada, among others. With 13 votes in favor and two abstentions (Russia and China), the UN Security Council (UNSC) approved resolution 2699 to initiate an international mission. Previously, analysts had anticipated that Russia and China may have used their veto power in the United Nations Security Council to block the intervention. The ruling on the multinational force was written by the US and will be carried out by 1,000 Kenyan soldiers. Technically, the intervention will not constitute a UN mission; as a result, UN member states will not be obliged to contribute to the intervention. Instead, the US has announced that it will contribute $200 million to the military intervention. In addition, the US Department of Defense, the branch of the US government directly responsible for the United States Armed Forces, will foot half the bill, according to the Miami Herald. “The so-called ‘multinational security support mission’ in Haiti is not an actual UN mission,” wrote geopolitical analyst Ben Norton on the subject. “It is a US military intervention, using the UN and Kenya as cover. The US wrote the UN resolution. The US is overseeing the operation. The [US] Defense Department is funding it.” The resolution specifies that the military operation will last one year, with a review after nine months. Although the intervention aims to address rising violence as a result of crimes, the US and its allies, to date, have focused their efforts on isolating the controversial figure of Jimmy “Barbecue” Cherizier and his G9 organization, which has, in reality, sought to broker peace deals between Haiti’s warring criminal factions. The resolution will be deployed in coming months, according to US Secretary of State Antony Blinken. A coalition of organizations composed of Haitians living in the US has recently demanded that the Biden administration end its support for Haiti’s unelected regime. Henry was appointed as leader of Haiti after the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July 2021. Although the case is still ongoing and the investigation is being led by US authorities, it appears that mercenaries, mostly Colombian, were hired by a Miami, USA-based company to carry out the killing of Moïse. On Friday, September 22, the National Haitian-American Elected Officials Network (NHAEON) and Family Action Network Movement (FANM) wrote to Biden and Secretary of State Antony Blinken with the request. “Any military intervention supporting Haiti’s corrupt, repressive, unelected regime will likely exacerbate its current political crisis to a catastrophic one,” they wrote. “It will further entrench the regime, deepening Haiti’s political crisis while generating significant civilian casualties and migration pressure.” “This regime has dismantled Haiti’s democratic structures while facilitating and conceding control of the country to many gang leaders. The PHTK governments did not run a fair or timely election,” the letter added. “They have created a prevalent culture of corruption that deprives the government of the necessary funds to support the Haiti National Police and provide basic governmental services to the Haitian population.” Kenya, a country of almost 55 million inhabitants, announced last July its willingness to send a thousand troops and thus assume a supporting role in the intervention. Sensing that Kenya, as an African nation, is largely being used as a proxy for the US military, which remains greatly unpopular in Haiti, Kenyan journalists and social movements have criticized the use of their country’s military in such a manner. Activists have complained that Kenya has “allowed itself to serve the agenda of white imperialists who continue to fund the criminal mafias in Haiti to destabilise it but pretend to mean good to it,” writes Nairobi-based journalist Gordon Osen. Haitian protester holds an anti-US sign during a protest against the unelected, US-backed Haitian regime, in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, on Oct. 17, 2022. Photo: Richard Pierrin/AFP. The intervention was approved by the military council despite arguments made against intervention last December by Haiti Liberté’s Kim Ives, speaking before the UN Security Council. “The facts themselves are not neutral,” said Ives at that time. “They speak to a history in which international law has been violated and the principles of peace and self-determination on which this body was founded have been trampled. These precedents have spawned the current crisis in the past three decades. Haiti has been the victim of three coup d’etats — in 1991, 2004, and, most recently, 2021. After each of these crimes, which involved international actors, the UN Security Council has been asked, as it is being asked today, to militarily intervene in Haiti. The council agreed to do so in the first two cases, thereby essentially cementing in place an unjust and illegal status quo. “The victims of these coups, the Haitian masses, were the ones policed, repressed, terrorized, demonized sexually, violated, politically bullied, and economically sanctioned. That is why the 16 million Haitian people — 12 million living in Haiti and some four million living abroad — are patently, and almost universally, opposed to any more UN interventions, with the exception of Haiti’s tiny bourgeoisie.” The 2010 United Nations intervention in Haiti infamously introduced cholera to the country, resulting in over 600,000 cases and approximately 10,000 preventable deaths. Author Steve Lalla is a journalist, researcher and analyst. His areas of interest include geopolitics, history, and current affairs. He has contributed to Counterpunch, Resumen LatinoAmericano English, ANTICONQUISTA, Orinoco Tribune, and others. Republished from Lalla's Medium. Archives October 2023 10/2/2023 What Every Child Should Know about Marx’s Theory of Value. By: Michael A. LebowitzRead NowEvery child knows that any nation that stopped working, not for a year, but let us say, just for a few weeks, would perish. And every child knows, too, that the amounts of products corresponding to the differing amounts of needs demand differing and quantitatively determined amounts of society’s aggregate labour. —Karl Marx [1] [2] Every child in Marx’s day might have heard about Robinson Crusoe. That child might have heard that on his island Robinson had to work if he was not to perish, that he had “needs to satisfy.” To this end, Robinson had to “perform useful labours of various kinds”: he made means of production (tools), and he hunted and fished for immediate consumption. These were diverse functions, but all were “only different modes of human labour,” his labor. From experience, he developed Robinson’s Rule: “Necessity itself compels him to divide his time with precision between his different functions.” Thus, he learned that the amount of time spent on each activity depended upon its difficulty—that is, how much labor was necessary to achieve the desired effect. Given his needs, he learned how to allocate his labor in order to survive. [3] As it was for Crusoe, so it is for society. Every society must allocate its aggregate labor in such a way as to obtain the amounts of products corresponding to the differing amounts of its needs. As Marx commented, “In so far as society wants to satisfy its needs, and have an article produced for this purpose, it has to pay for it.… It buys them with a certain quantity of the labour-time that it has at its disposal.” [4] It must allocate “differing and quantitatively determined” amounts of labor to the production of goods and services for direct consumption (Department II) and a similarly determined quantity of labor for the production and reproduction of means of production (Department I). To ensure the reproduction of a particular society, there must be enough labor available for the reproduction of the producers—both directly and indirectly (for example, in Departments II and I, respectively)—based upon their existing level of needs and the productivity of labor. This includes not only labor in organized workplaces, which produce particular material products and services, but also necessary labor allocated to the home and community and to sites where the education and health of workers are maintained. Every society, too, must allocate labor to what we may call Department III, a sector that produces means of regulation, and may contain institutions such as the police, the legal authority, the ideological and cultural apparatus, and so on. In addition to the labor required to maintain the producers, in every class society a quantity of society’s labor is necessary if those who rule are to be reproduced. Thus, the process of reproduction requires the allocation of labor not only to the production of articles of consumption, means of production, and the particular means of regulation, but, ultimately, to the production and reproduction of the relations of production themselves. REPRODUCTION OF A SOCIALIST SOCIETY Consider a socialist society—“an association of free [individuals], working with the means of production held in common, and expending their many different forms of labour-power in full self-awareness as one single social labour force.” [5] Having identified the differing amounts of needs it wishes to satisfy, this society of associated producers allocates its differing and quantitatively determined labor through a conscious process of planning. In this respect, it follows Robinson’s Rule: it apportions its aggregate labor “in accordance with a definite social plan [that] maintains the correct proportion between the different functions of labour and the various needs of the associations.” [6] The premise of this process of planning is a particular set of relations in which the associated producers recognize their interdependence and engage in productive activity upon this basis. “A communal production, communality, is presupposed as the basis of production.” Transparency and solidarity among the producers, in short, underlie the “organization of labour” in the socialist society with the result that productive activity is consciously “determined by communal needs and communal purposes.” [7] The reproduction of society here “becomes production by freely associated [producers] and stands under their conscious and planned control.” [8] To identify their needs and their capacity to satisfy those needs, the producers begin with institutions closest to them—in communal councils, which identify changes in the expressed needs of individuals and communities, and in workers’ councils, where workers explore the potential for satisfying local needs themselves. Those needs and capacities are transmitted upward to larger bodies and ultimately consolidated at the level of society as a whole, where society-wide choices need to be made. On the basis of these decisions (which are discussed by the associated producers at all levels of society), the socialist society directly allocates its labor in accordance with its needs both for immediate and future satisfaction. Driving this process is “the worker’s own need for development,” “the absolute working-out of his creative potentialities,” “the all-around development of the individual”—the development of what Marx called “rich” human beings. [9] This goal is understood as indivisible: it is not consistent with significant disparities among members of society. In the words of the Communist Manifesto, “the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.” [10] Accordingly, given the premise of communality and solidarity, this socialist society allocates its labor to remove deficits inherited from previous social formations. The socialist society, in short, is “based on the universal development of individuals and on the subordination of their communal, social productivity as their social wealth.” [11] Conscious planning—a visible hand, a communal hand—is the condition for building a socialist society. This process does more, however, than produce the so-called correct plan. Importantly, it also produces and reproduces the producers themselves and the relations among them. What Marx called “revolutionary practice” (“the simultaneous changing of circumstances and human activity or self-change”) is central. Every human activity produces two products: the change in circumstances and the change in the actors themselves. In the particular case of socialist institutions, the labor-time spent in meetings to develop collective decisions not only produces solutions that draw upon the knowledge of all those affected, but it is also an investment that develops the capacities of all those making those decisions. It builds solidarity locally, nationally, and internationally. Those institutions and practices, in short, are at the core of the regulation of the producers themselves (Department III activity). They are essential for the reproduction of socialist society. [12] REPRODUCTION OF A SOCIETY CHARACTERIZED BY COMMODITY PRODUCTION But what about a society that is not characterized by communality, a society marked instead by separate, autonomous actors? Such a society’s essential premise is the separation of independent producers. [13] Rather than a community of producers, there is a collection of autonomous property owners who depend for satisfaction of their needs upon the productive activity of other owners. “All-around dependence of the producers upon one another” exists, but theirs is a “connection of mutually indifferent persons.” Indeed, “their mutual interconnection—here appears as something alien to them, autonomous, as a thing.” Yet, if these “individuals who are indifferent to one another” do not understand their connection, how does this society go about allocating its “differing and quantitatively determined amounts of society’s aggregate labour” to satisfy its “differing amounts of needs”? [14] Obviously, such a society does not utilize Robinson’s Rule: it cannot directly allocate its aggregate labor in accordance with the distribution of its needs. “Only when production is subjected to the genuine, prior control of society,” Marx pointed out, “will society establish the connection between the amount of social labor-time applied to the production of particular articles, and the scale of the social need to be satisfied by these.” [15] Although the application of Robinson’s Rule is not possible, its function remains. As Marx commented, those simple and transparent relations set out for Robinson Crusoe “contain all the essential determinants of value.” [16] In particular, the “necessity of the distribution of social labour in specific proportions” remains. The necessary law of the proportionate allocation of aggregate labor, Marx insisted, “is certainly not abolished by the specific form of social production.” Only the form of that law changes. As Marx wrote to Ludwig Kugelmann, “the only thing that can change, under historically differing conditions, is the form in which those laws assert themselves.” In the commodity-producing society, the form taken by this necessary law is the law of value. “The form in which this proportional distribution of labour asserts itself in a state of society in which the interconnection of social labour expresses itself as the private exchange of the individual products of labour, is precisely the exchange value of these products.” [17] Since the allocation of society’s labor embedded in commodities is “mediated through the purchase and sale of the products of different branches of industry” (rather than through “genuine, prior control” by society), however, the immediate effect of the market is a “motley pattern of distribution of the producers and their means of production.” [18] Yet, this apparent chaos sets in motion a process by which the necessary allocation of labor will tend to emerge. In simple commodity production, some producers will receive revenue well above the cost of production; others will receive revenue well below it. Assuming it is possible, producers will shift their activity—that is, they will show a tendency for entry and exit. An equilibrium, accordingly, would tend to emerge in which there is no longer a reason for individual commodity producers to move. Through such movements, the various kinds of labor “are continually being reduced to the quantitative proportions in which society requires them.” In short, although “the play of caprice and chance” means that the allocation of labor does not correspond immediately to the distribution of needs as expressed in commodity purchases, “the different spheres of production constantly tend towards equilibrium.” [19] Through the law of value, labor is allocated in the necessary proportions in the commodity-producing society. In the same way as “the law of gravity asserts itself,” we see that “in the midst of the accidental and ever-fluctuating exchange relations between the products, the labour-time socially necessary to produce them asserts itself as a regulative law of nature.” [20] There is a “constant tendency on the part of the various spheres of production towards equilibrium” precisely because “the law of the value of commodities ultimately determines how much of its disposable labour-time society can expend on each kind of commodity.” [21] Can that equilibrium, in which labor is allocated to satisfy the needs of society, be reached in reality? If we think of a society characterized by simple commodity production, equilibrium occurs when all commodity producers receive the equivalent of the labor contained in their commodities. In fact, however, there are significant barriers to exit and entry: the particular skills and capabilities that individual producers possess will not be easily shifted to the production of differing commodities. Indeed, this process might take a generation to occur, in which case producers in some spheres will appear privileged for extended periods. In the case of capitalist commodity production—the subject of Capital—the individual capitalist “obeys the immanent law, and hence the moral imperative, of capital to produce as much surplus-value as possible.” [22] Accordingly, there is a “continuously changing proportionate distribution of the total social capital between the various spheres of production…continuous immigration and emigration of capitals.” [23] Equilibrium here occurs when all producers obtain an equal rate of profit on their advanced capital for means of production and labor power. This tendency “has the effect of distributing the total mass of social labour time among the various spheres of production according to the social need.” [24] However, here again there is an obstacle to the realization of equilibrium—the existence of fixed capital embedded in particular spheres does not permit easy exit and entry. Nevertheless, for Marx, the law of value (the process by which labor is allocated in the necessary proportions in capitalism) operates more smoothly as capitalism develops. Capital’s “free movement between these various spheres of production as so many available fields of investment” has as its condition the development of the credit and banking system. Only as money-capital does capital really “possess the form in which it is distributed as a common element among these various spheres, among the capitalist class, quite irrespective of its particular application, according to the production requirements of each particular sphere.” [25] In its money-form, capital is abstracted from particular employments. Only in money-capital, in the money-market, do all distinctions as to the quality of capital disappear: “All particular forms of capital, arising from its investment in particular spheres of production or circulation, are obliterated here. It exists here in the undifferentiated, self-identical form of independent value, of money.” [26] Equalization of profit rates “presupposes the development of the credit system, which concentrates together the inorganic mass of available social capital vis-á-vis the individual capitalist.” [27] That is, it presupposes the domination of finance capital: bankers “become the general managers of money capital,” which now appears as “a concentrated and organized mass, placed under the control of the bankers as representatives of the social capital in a quite different manner to real production.” [28] MARX’S AUTO-CRITIQUE There is no better way to understand Marx’s theory of value than to see how he responded to critics of Capital. With respect to a particular review, Marx commented to Kugelmann in July 1868 that the need to prove the law of value reveals “complete ignorance both of the subject under discussion and of the method of science.” Every child, Marx here continued, knows that “the amounts of products corresponding to the differing amounts of needs demand differing and quantitatively determined amounts of society’s aggregate labour.” How could the critic not see that “It is SELF-EVIDENT that this necessity of the distribution of social labour in specific proportions is certainly not abolished by the specific form of social production!” [29] Similarly, answering Eugen Dühring’s objection to his discussion of value, Marx wrote to Frederick Engels in January 1868 that “actually, no form of society can prevent the labour time at the disposal of society from regulating production in ONE WAY OR ANOTHER.” [30] That was the point: in a commodity-producing society, how else could labor be allocated—except by the market! Although Marx was clearer in these letters on this point than in Capital, he was transparent there in his critique of classical political economy on value and money. In contrast to vulgar economists who did not go beneath the surface, the classical economists (to their credit) had attempted “to grasp the inner connection in contrast to the multiplicity of outward forms.” But they took those inner forms “as given premises” and were “not interested in elaborating how those various forms come into being.” [31] The classical economists began by explaining relative value by the quantity of labor-time, but they “never once asked the question why this content has assumed that particular form, that is to say, why labour is expressed in value, and why the measurement of labour by its duration is expressed in the value of the product.” [32] Their analysis, in short, started in the middle. This classical approach characterized Marx’s own early thought. It is important to recognize that Marx’s critique was an auto-critique, a critique of views he himself had earlier accepted. In 1847, Marx declared that “[David] Ricardo’s theory of values is the scientific interpretation of actual economic life.” [33] In The Principles of Political Economy, Ricardo had argued that “the value of a commodity…depends on the relative quantity of labour which is necessary for its production.” By this, he meant “not only the labour applied immediately to commodities,” but also the labor “bestowed on the implements, tools, and buildings, with which such labour is assisted.” Accordingly, relative values of differing commodities were determined by “the total quantity of labour necessary to manufacture them and bring them to market.” This was “the rule which determines the respective quantities of goods which shall be given in exchange for each other.” [34] Marx followed Ricardo in his early work. “The fluctuations of supply and demand,” Marx wrote in Wage Labour and Capital, “continually bring the price of a commodity back to the cost of production” (that is to say, to its “natural price”). This was Ricardo’s theory of value: the “determination of price by the cost of production is equivalent to the determination of price by the labour time necessary for the manufacture of a commodity.” Further, this rule applied to the determination of wages as well, which were “determined by the cost of production, by the labour time necessary to produce this commodity—labour.” [35] The same point was made in the Communist Manifesto in 1848: “the price of a commodity, and therefore also of labour, is equal to its cost of production.” [36] In the 1850s, however, Marx began to develop a new understanding. In the notebooks written in 1857–58, which constitute the Grundrisse, he began his critique of classical political economy. Marx concluded the Grundrisse by announcing that the starting point for analysis had to be not value (as Ricardo began), but the commodity, which “appears as unity of two aspects”—use value and exchange value. [37] The commodity and, in particular, its two-sidedness is the starting point for his critique and how he begins both his Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859) and Capital. [38] THE BEST POINTS IN CAPITAL The law of value as a “regulative law of nature” was not one of the best points in Capital, nor one of the “fundamentally new elements in the book.” After all, if the law of value is the tendency of market prices to approach an equilibrium in the same way as “the law of gravity asserts itself,” then this “regulative law of nature” was already present in Ricardo. Rather, what Marx argued in Capital is that classical political economy did not understand value. “As regards value in general, classical political economy in fact nowhere distinguishes explicitly and with a clear awareness between labour as it appears in the value of a product, and the same labour as it appears in the product’s use value.” [39] But that distinction, Marx declared to Engels in August 1867, is “fundamental to all understanding of the FACTS”! That “two-fold character of labour,” he indicated, is one of the “best points in my book” (and indeed, the best point in the first volume of Capital). [40] Marx made the same point in the first edition of the first volume of Capital about the two-fold character of labor in commodities: “this aspect, which I am first to have developed in a critical way, is the starting point upon which comprehension of political economy depends.” [41] Writing again to Engels in January 1868, Marx described his analysis of the double character of the labor represented in commodities as one of the “three fundamentally new elements of the book.” All previous economists having missed this, they were “bound to come up against the inexplicable everywhere. This is, in fact, the whole secret of the critical conception.” [42] The secret of the critical conception, the starting point for comprehension of political economy, the basis for all understanding of the facts—what made the revelation of the two-fold character of labor in commodities so important? Very simply, it is the recognition that actual, specific, concrete labor, all those hours of real labor that have gone into producing a particular commodity, in themselves have nothing to do with its value. You cannot add the hours of the carpenter’s labor to the labor contained in consumed means of production and come up with the value of the carpenter’s commodity. That specific labor, rather, has gone into the production of a thing for use, also known as a use value. Further, you cannot explain relative values by counting the quantity of specific labor contained in separate use values. If you do not distinguish clearly between the two-fold aspects of labor in the commodity, you have not understood Marx’s critique of classical political economy. MARX’S LABOR THEORY OF MONEY “We have to perform a task,” Marx announced, “never even attempted by bourgeois economics.” [43] That task was to develop his theory of money—in particular, to reveal that money is the social representative of the aggregate labor in commodities. For this, Marx demonstrated that (1) the concept of money is latent in the concept of the commodity and (2) that money represents the abstract labor in a commodity and that the manifestation of the latter, its only manifestation, is the price of the commodity. If adding up the hours of concrete labor to produce a commodity does not reveal its value, what does? Nothing, if we are considering a single commodity. “We may twist and turn a single commodity as we wish; it remains impossible to grasp as a thing possessing value.” [44] We can approach grasping the value of a commodity only by considering it in a relation. The simplest (but undeveloped) form of this relation is as an exchange value—the value of commodity A is equal to x units of commodity B, where B is a use value. We always knew A as a use value but now we know the value of A from its equivalent in B. (If we reverse this, we would say the value of B is equal to 1/x units of A, and here A is the equivalent.) The second commodity, the equivalent, is a mirror for the value in the first commodity. It is through this social relation that we may grasp the commodity as something possessing value. Having established that the value of a commodity is revealed through its equivalent, Marx logically proceeds step-by-step to establish the existence of a commodity that serves as the equivalent for all commodities—that is, is the general form of value. It is a mini-step from there to reveal the monetary form of value: money as the universal equivalent, money as the representative of value. [45] In short, once we begin to analyze a commodity-exchanging society, we are led to the concept of money. This is what Marx identifies as his task: “We have to show the origin of this money form, we have to trace the development of this expression of value relation of commodities from the simplest, almost imperceptible outline to the dazzling money form. When this has been done, the mystery of money will immediately disappear.” [46] But this was a closed book to the classical economists; “Ricardo,” Marx commented years later, “in fact only concerned himself with labour as a measure of value-magnitude and therefore found no connection between his value-theory and the essence of money.” [47] But what is money? To understand money, we need to return to the two-fold character of labor in commodities, that point upon which comprehension of political economy depends. We know that concrete, specific labor produces specific use values. Insofar as labor is concrete, we cannot compare commodities containing different qualities of labor. But we can compare them if we abstract from their specificities—that is, consider them as containing labor in general, abstract labor, “equal human labour, the expenditure of identical human labour power.” [48] The aggregate labor of society is a composite of many “different modes of human labour”: “the completed or total form of appearance of human labour is constituted by the totality of its particular forms of appearance.” [49] That “one homogeneous mass of human labour power,” that universal, uniform, abstract, social labor in general, “human labour pure and simple,” enters into each commodity. [50] Think about the aggregate labor in commodities as so-called jelly labor, as made up of a number of identical, homogeneous units. A certain amount of this jelly labor goes into each commodity. The value of a commodity is determined by how much of this jelly labor—how much homogeneous, universal, abstract labor, that common “social substance”—it contains. Obviously, we cannot add up jelly labor simply, as we might attempt for concrete labor. How, then, can we see the value of a commodity? We have answered that already. The value of a commodity (that is, the homogeneous, general, abstract labor in the commodity) is represented by the quantity of money, which is its equivalent. Indeed, the only form in which the value of commodities can manifest itself is the money-form. Every society obtains the amounts of products corresponding to the differing amounts of its needs by devoting a portion of the available labor time to its production. As noted above, “in so far as society wants to satisfy its needs, and have an article produced for this purpose, it has to pay for it…[and] it buys them with a certain quantity of the labour-time that it has at its disposal.” [51] How do we satisfy our needs within capitalism? We buy them with the representative of the total social labor in commodities—money. IGNORANCE BOTH OF THE SUBJECT UNDER DISCUSSION AND OF THE METHOD OF SCIENCE As Michael Heinrich writes, “many Marxists have difficulties understanding Marx’s analysis.” Like bourgeois economists, “they attempt to develop a theory of value without reference to money.” [52] It is a bit difficult to understand why, however, given Marx’s criticisms of classical political economy about this very point. Ricardo, Marx commented, had not understood “or even raised as a problem” the “connection between value, its immanent measure—i.e., labour-time—and the necessity for an external measure of the values of commodities.” Ricardo did not examine abstract labor, the labor that “manifests itself in exchange values—the nature of this labour. Hence he does not grasp the connection of this labour with money or that it must assume the form of money.” [53] That is why Marx undertook his task “to show the origin of this money form” and to solve “the mystery of money,” a task “never even attempted by bourgeois economics.” We need to understand the nature of money, and how we move from value directly to money. As he explained in chapter 10 of the third volume of Capital: in dealing with money we assumed that commodities are sold at their values; there was no reason at all to consider prices that diverged from values, as we were concerned simply with the changes of form which commodities undergo when they are turned into money and then transformed back from money into commodities again. As soon as a commodity is in any way sold, and a new commodity bought with the proceeds, we have the entire metamorphosis before us, and it is completely immaterial here whether the commodity’s price is above or below its value. The commodity’s value remains important as the basis, since any rational understanding of money has to start from this foundation, and price, in its general concept, is simply value in the money form. [54] To understand why Marx felt it was essential to solve the mystery of money, it helps to understand his method of dialectical derivation. Like G. W. F. Hegel, upon examining particular concepts, he found that they contained a second term implicitly within them; he proceeded then to consider the unity of the two concepts, thereby transcending the one-sidedness of each and moving forward to richer concepts. In this way, Marx analyzed the commodity and found that it contained latent within it the concept of money, the independent form of value—and that the commodity differentiated into commodities and money. Further, considering that relation of commodities and money from all sides, Marx uncovered the concept of capital. [55] The concept of capital, in short, does not drop from the sky. It is marked by the preceding categories. Since money is the representative of abstract labor, of the homogeneous aggregate labor of society, capital must be understood as an accumulation of homogeneous, abstract labor. By understanding money as latent in commodities, we reject the picture of money juxtaposed externally to commodities as in classical political economy and therefore recognize that abstract labor is always present in the concept of capital. However, all accumulations of abstract labor are not capital. For them to correspond to the concept of capital, they must be driven by the impetus to grow and must have self-expanding value (i.e., M-C-M´). How is that possible, however, on the assumption of exchange of equivalents? Where does the additional value, the surplus value, come from? The two questions express the same thing: in one case, in the form of objectified labour; in the other, in the form of living, fluid labor. [56] The answer to both is that, with the availability of labor power as a commodity, capital can now secure additional (abstract) labor. This is not because of some occult quality of labor power, but, because by purchasing labor power, capital now is in a relation of “supremacy and subordination” with respect to workers, a relation that brings with it the “compulsion to perform surplus labour.” [57] That compulsion, inherent in capitalist relations of production, is the source of capital’s growth. Let us consider absolute surplus value by focusing upon “living, fluid labor.” The value of labor power, or necessary labor, at any given point represents the share of aggregate social labor that goes to workers. The remaining social labor share is captured by capitalists. When capital uses its power to increase the length or intensity of the workday, total social labor rises; assuming necessary labor remains constant, capital is the sole beneficiary. The ratio of surplus labor to necessary labor—the rate of exploitation—rises. Alternatively, let the productivity of labor be increased. To produce the same quantity of use values, less total labor is required. Accordingly, increased productivity brings with it the possibility of a reduced workday (a possibility not realized in capitalism). If, conversely, aggregate social labor remains constant, who would be the beneficiary of such an increase in productivity? Assuming the working class is atomized and capital is able to divide workers sufficiently, capital obtains relative surplus value because necessary labor falls. Alternatively, to the extent that workers are sufficiently organized as a class, they will benefit from productivity gains with rising real wages as commodity values fall. In Capital, this second option is essentially precluded because, following the classical economists, Marx assumed that the standard of necessity is given and fixed. [58] In short, we need to understand money if we are to understand capital, and for that we need to grasp the two-fold character of labor that goes into a commodity. Unfortunately, many Marxists fail to grasp the distinction “between labour as it appears in the value of a product, and the same labor as it appears in the product’s use value”—the distinction Marx considered “fundamental to all understanding of the FACTS.” As a result, they offer a “theory of value without reference to money,” what Heinrich calls “pre-monetary theories of value,” which I consider to be pre-Marxian theories of value or Ricardian theories of value. [59] Ricardian Marxists do not grasp Marx’s logic, or how Marx logically moves from the abstract to the concrete. The problem is particularly apparent when it comes to the so-called transformation problem. What those who attempt to calculate the transformation from values to prices of production fail to understand is that, rather than transforming actually existing values, prices of production are simply a further logical development of value. [60] The real movement is from market prices to equilibrium prices, that is, prices of production. As we have seen, this is how the law of value allocates aggregate labor in commodities, similar to a law of gravity. The failure of these Marxists to distinguish between the logical and the real demonstrates their “complete ignorance both of the subject under discussion and of the method of science.” NOTES

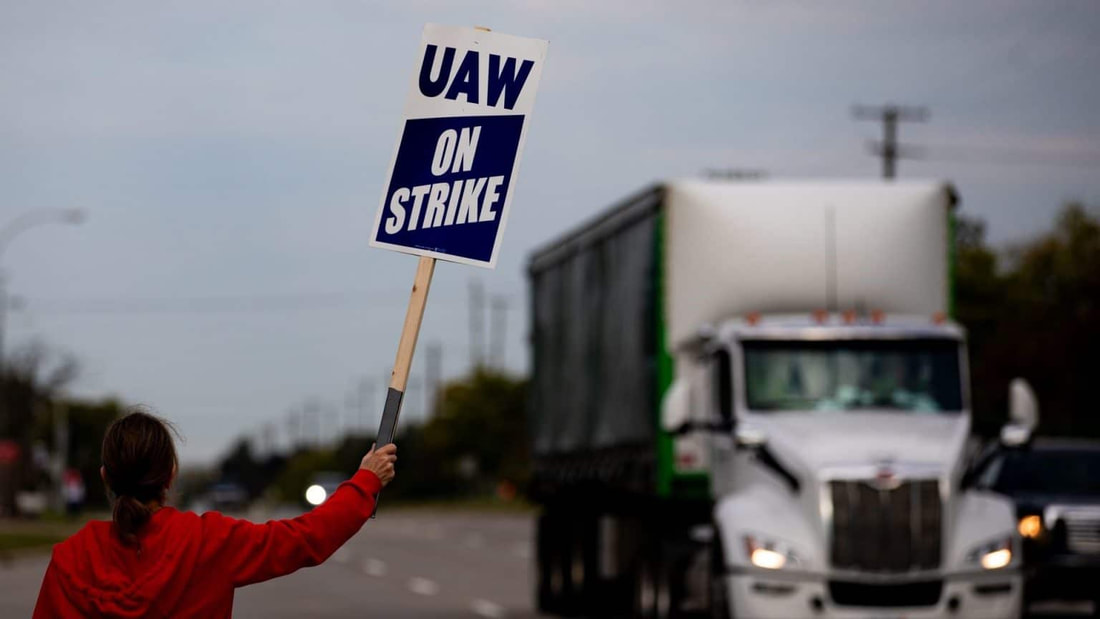

Author Michael A. Lebowitz was a professor of economics at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver until his death on April 19, 2023. For information on his life and work, see the “Notes from the Editors,” Monthly Review, July–August 2023. Republished from Monthly Review. Archives October 2023 10/2/2023 The Big Three Are Using Layoffs to Punish the UAW and Undermine the Strike. By: James Dennis HoffRead NowThe Big Three are retaliating against the UAW by laying off thousands of its members at plants across the country. Defeating these attacks will require the self organization and mobilization of all the workers. In a clear act of retaliation against striking auto workers, the Big Three have laid off thousands of employees since the United Auto Workers (UAW) strikes began on September 15. At Ford, more than 600 non-striking workers were laid off at the Wayne, Michigan plant just two days after the strike began. Meanwhile, GM and Stellantis have laid off a combined 3,000 workers, with more layoffs expected. At the same time, a number of auto suppliers for the Big Three have also been laying off substantial portions of their own workforces to retaliate against the UAW strike. If the strike continues for several more weeks or months, it is quite possible that these layoffs (and the use of scab labor) will increase exponentially, as the companies seek to protect profits and divide the workforce in order to weaken the strike. Directly confronting and resisting these layoffs must be a central task of the entire union if they wish to protect their jobs, win their demands, and build union solidarity. While the UAW has condemned the layoffs, the auto companies claim that they are an inevitable result of the strike, which, by disrupting manufacturing and distribution across several major plants, has left many other workplaces without the necessary materials needed to continue production. However, it’s important to note that these layoffs are not only a corporate response to the chaos created by the strike; they are quite obviously an explicit tool of retaliation that the auto companies are using to punish the UAW and its members in order to break the strike. As UAW president Shawn Fain said in a response to the layoffs: “if the Big Three decide to lay people off who aren’t on strike, that’s them trying to put the squeeze on our members to settle for less.” Fain also made the point that the layoffs were unnecessary, and the company could afford to continue paying those laid-off workers. With more than $20 billion in combined profits for just the first half of this year, they definitely could. But these layoffs are not only about squeezing workers — they are also part of a clear strategy by the Big Three to try to withstand the worst effects of the strike at the expense of the workers themselves. GM, Ford, and Stellantis, though they continue to rake in record profits, are using these layoffs to save millions in wages while simultaneously sowing fear and insecurity among all of those not yet on strike, many of whom could be laid off at a moment’s notice. This is a clear attempt not only to put pressure on the strikers, as Fain explains, but to create divisions within the union and among different sectors of workers — those still receiving paychecks, those receiving strike pay, and those being laid off. Meanwhile, the companies are using the state and bourgeois law to punish workers even further by refusing to pay contractually-obligated supplementary unemployment benefits, and arguing that those laid off during a strike do not qualify for state unemployment. This claim may prove to be true for some workers, thanks to anti-worker “right to work” legislation in several states like Kansas and Michigan (which is still a right-to-work state until March 2024), where layoffs are taking place. It is not out of the question that management will try to make these layoffs permanent as further punishment against the strike and the bold demands the union is putting forward. This makes it necessary for the union to stop the “business as usual” approach to layoffs. They have to treat this act of retaliation as a serious threat that requires a direct response, and not simply rely on the law or the courts, which fail the working class all the time. Although the stand-up strike strategy has allowed Fain and the UAW to gain public support while also causing chaos within the production processes of the Big Three, the top-down nature of the struggle so far means that these laid-off workers, and many others, have no agency in decisions about their strike, or about fighting layoffs. To ensure these workers are compensated and get their jobs back, the rank and file must demand that the strike take up the reinstatement of all workers laid off in the UAW and related industries directly as part of its demands. In order to fight these layoffs, the UAW should organize meetings in every single local to unite all workers — those on strike, those who are not on strike, and those who have been laid off. This would allow workers (many of whom are already organizing flying squadrons, fighting management on the floor, and refusing to work overtime) to discuss together how to continue the strike, how to resist scabs, and how to develop a strategy that can best fight these layoffs both during the strike and after. Every new wave of layoffs should be met with further walkouts and an escalation of the strike. The members should make sure that any new contract guarantees that laid-off workers are rehired and receive compensation for lost wages. But beating the Big Three and building a union capable of defending those gains will require the collective efforts, creative energy, and active engagement of all of the membership, not only the elected leaders, staff, and bureaucrats. Every worker is capable of leading, and ultimately, it is the workers themselves who are on the front lines of struggle every day and who know best how to organize themselves to fight the bosses. This is why self organization, in the form of strike committees and mass meetings of rank-and-file workers, is so important. Such a self-directed struggle against these layoffs would not only create greater solidarity among workers within the union, but would help to build the kind of organization needed to weather a strike long enough to win all of their demands, including the bold demand for a 32 hour workweek, which could be an essential part of the fight against layoffs as the industry transitions to the production of electric vehicles. Just as the workers of the great GM sit-down strikes and their communities and families did in 1937, rank-and-file auto workers, alongside workers across the country, have it in their power today to rebuild a fighting labor movement. Author James Dennis Hoff is a writer, educator, labor activist, and member of the Left Voice editorial board. He teaches at The City University of New York. Republished from Left Voice. Archives October 2023 10/2/2023 “The workers are the liberators,” declares UAW President, sending 7,000 more out on strike. By: Natalia MarquesRead NowUnited Auto Workers are expanding their strike to put additional pressure on General Motors and Ford, playing the three largest automakers against each other On September 29, United Auto Workers (UAW) President Shawn Fain announced that 7,000 more unionized auto workers are going out on strike, to join the 18,000 workers already participating in the “Stand Up Strike” against the three largest automakers in the United States. Since 146,000 UAW auto workers saw their master contract expire with the three largest automakers (Ford, Stellantis, and General Motors) on September 14, the UAW has implemented the unique “Stand Up Strike” method. Instead of sending all 146,000 Big Three auto workers out on strike in one fell swoop, the union is having workers walk off the job in waves. This ensures that the companies are always on their toes—already causing the corporations to miscalculate and prepare for strikes at the wrong plants. The two additional plants called out on strike are General Motors’ Lansing Delta Township Assembly in Michigan and Ford’s Chicago Assembly plant. The union decided to go easier on Stellantis this time around, although the union had originally planned to expand the strike for all the Big Three this Friday. Shortly before Shawn Fain was to make his weekly Stand Up Strike announcement, Stellantis sent some last minute emails to the union, acquiescing to worker demands around cost of living allowances (COLA), the right not to cross a picket line, and the right to strike over product commitments and plant closures. Ford was spared last week because of significant progress the union had made on its central demands at that company, and UAW instead elected to send all Stellantis and Ford parts distribution centers out on strike. But as Jane Slaughter writes in Labor Notes, “Today the UAW once again called out workers at Ford and GM, putting some muscle behind its bold demands—a big wage boost, a shorter work week, elimination of tiers, cost-of-living adjustments tied to inflation, protection from plant closures, conversion of temps to permanent employees, and the restoration of retiree health care and benefit-defined pensions to all workers.” In his announcement of the 7,000 workers newly on strike, Shawn Fain referenced US President Joe Biden’s visit to a UAW picket line this week, marking the first time a sitting US President has ever visited a picket line. During his visit, Biden expressed open support for UAW’s demand for a 40% wage increase. “Companies were in trouble, now they’re doing incredibly well. And guess what? You should be doing incredibly well, too,” Biden said to striking workers, referencing the 2009 government bailout of the auto industry. “You deserve what you’ve earned. And you’ve earned a helluva lot more than what you’re getting paid now.” But Fain was not about to give Biden a pat on the back simply for showing up. On Friday, the UAW leader was frank about what it took to get the President of the United States to show unequivocal support for striking workers. “The most powerful man in the world showed up for one reason only: because our solidarity is the most powerful force in the world.” On Friday, Fain referenced the historic plant that Biden had visited, the GM Willow Run facility in Michigan, “where UAW members built the B24 Liberator bombers during WWII.” “Our union was essential in building what was called the arsenal of democracy,” he said in a Facebook Live address to all UAW members and the rest of the public. “Just like 80 years ago, today our union is building a different arsenal of democracy. But this war isn’t against some foreign country. The frontlines are right here at home. It’s the war of the working class versus corporate greed. We are the new arsenal of democracy.” “The workers are the liberators and our strike is a vehicle for liberation,” he declared. Workers hold the line for a fair dealWhile the Stand Up Strike model has proven effective, the sheer excitement and anticipation of each non striking Big Three worksite is testament to the fighting spirit of these autoworkers. Peoples Dispatch spoke to Jeffrey Parcell, President of UAW Local 3039, whose members work at a Stellantis PDC in Tappan, New York. Tappan auto workers were asked to go out on strike after the first week, on September 22. When asked what it was like to work while the strike was ongoing, Parcell candidly said, “We were pissed. We wanted it to be us.” Finally walking out at noon last Friday was extremely satisfying to workers, Parcell said. Management had anticipated that if there were to be a walkout, it would happen at midnight, like it did with the first strike wave on September 14. Instead, Fain ordered Stellantis and GM PDCs to go on strike at noon Eastern Time. Parcell describes how underprepared management was, and how workers left everything on the shop floor and walked out at midday. At one point while workers were on the picket line, a supervisor walked out of the PDC, and workers reminded him that he wasn’t on break, telling him to get back inside and get back to work. In an economic system where the roles are almost always reversed, strikes offer a unique opportunity to give the bosses a taste of their own medicine. “The day we walked out, you know, we were ready to go,” Parcell said. The workers in Tappan are ready to hold the picket line for as long as it takes to reach a fair contract. “We’re prepared to go as long as we gotta go man. We dealt with the rain over the weekend, a lot of storms and stuff like that. We’re still out there 24/7 around the clock.” Patrick Paisley, a worker at the Tappan PDC for five years, was impressed with the solidarity other working people have shown on the picket line and at solidarity rallies in the surrounding area. “It’s not just for us,” he told Peoples Dispatch. “A lot of people have been taken for granted, you know. I’m hoping that the bigger heads can see that people want to be recognized, or at least compensated, or appreciated, whatever, you know?” Archives September 2023 |

Details

Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed