|

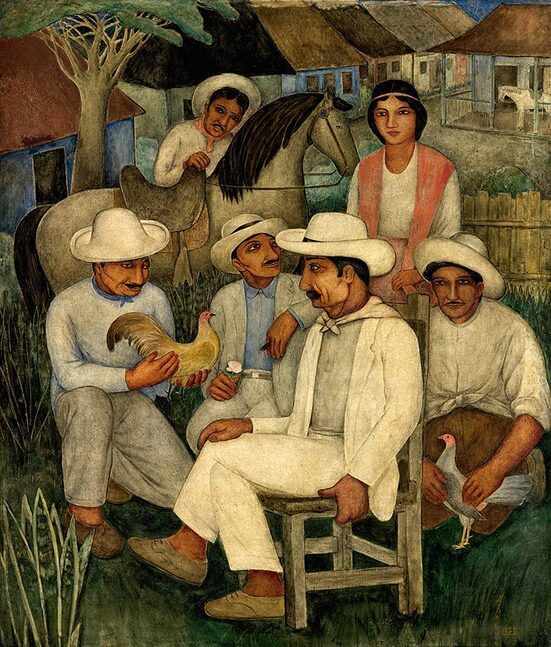

Workers decorate an office of the Kurdistan Communist Party - Iraq. With one lonely member of parliament, one might think the KCP is a marginal force, but its influence far outstrips its electoral performance. | Kurdistan TV via KCP SULAYMANIYAH, Iraqi Kurdistan—For those who have followed the development of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in northern Iraq since its formation after the Kurdish rebellion of 1991, the names Jalal Talabani and Massoud Barzani have been inextricably tied to the region’s politics. Their respective parties, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), have long dominated the political landscape, dividing the territory of the autonomous region between themselves after a period of intense inner-Kurdish warfare in the 1990s. Today, they each maintain their own Peshmerga military formations, and the KRG often appears to function as a one-party state, though paradoxically, there are two of them.

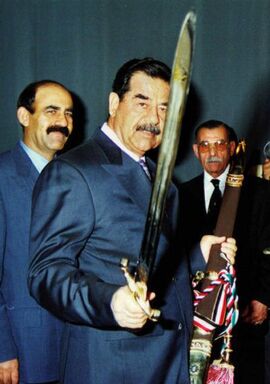

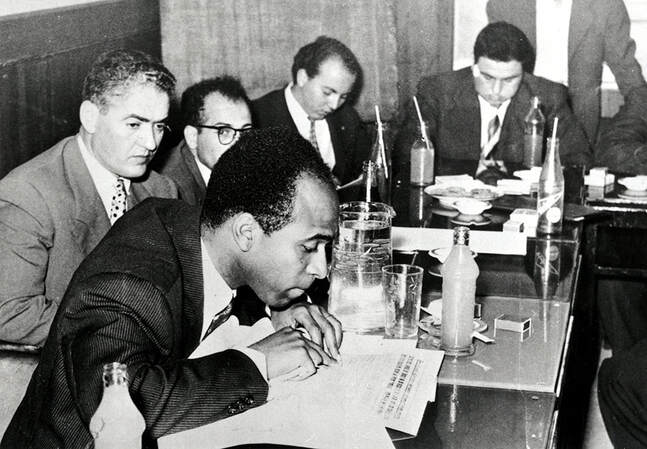

Then there is the oldest party in the Kurdistan Region, the Kurdistan Communist Party. With one lonely MP, one could be forgiven for having the impression that the Communists are a marginal force. The party’s influence and importance to the region, however, far outstrip its electoral performance. The rich history of the Iraqi/Kurdistan Communist Party The Kurdistan Communist Party was technically founded in 1993, although in reality this simply meant the branch of the Iraqi Communist Party (ICP) in what had become the Kurdistan Region was now solely responsible for its own affairs in the new de facto independent area. The Iraqi party dates its foundation back to 1934. It played a vital role in the formation of the country’s working-class organizations, including the establishment of trade unions. The party has experienced periods of legality and illegality throughout its existence and had a contradictory relationship with the Ba’ath Party that ruled the country for nearly four decades. In 1963, the U.S.-backed Ba’athist coup that deposed Abd al-Karim Qasim led to thousands of Communist Party members being slaughtered in the following days, with party leader Salam Adil among those executed. However, in the mid-1970s, relations between the Communist Party and the Ba’athists warmed somewhat, with the Communists initially viewing Saddam Hussein positively when he came to power, even referring to him in glowing terms as Iraq’s own variant of Fidel Castro in the aftermath of nationalization campaigns. This led to their inclusion in the National Progressive Front in 1975, which meant accepting the Ba’ath Party’s dominance over Iraqi political life. However, certain contradictions soon began to appear irreconcilable. The Communists were proud of their heritage as a multinational party and advocated an Iraqi state with full rights for both of its dominant nations, Arabs and Kurds. This had initially been the line of the Qasim government that had taken power in 1958, which the Communists generally supported. By contrast, the Ba’athist ideology could make no room for Kurds in its Arab nationalist orientation unless they agreed to a position of subservience and second-class citizenship.

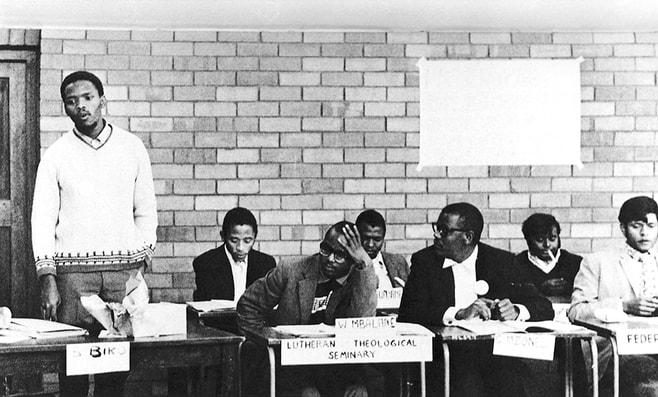

In Sulaymaniyah, where the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) is the dominant political force, I was able to speak with the Deputy Secretary-General for the Communist Party in the governorate, Hawre Gorran. On the right of nations to self-determination Gorran begins by making it clear that the KRG should be united, not divided into two camps that are each under the control of either the KDP or PUK. He is clear in his opposition to the vast privatization that has taken place under each party in the areas of health, education, and electricity, but also keenly aware that division between the Talabani and Barzani cliques has been catastrophic. “The Kurdistan Communist Party played a very important role in mediating between the KDP and PUK during the civil war that was fought between 1994 and 1997. Our leader at that time, Aziz Muhammad, helped bring them together to end the conflict,” he says. Muhammad, who passed away in 2017, was a legendary figure on the Kurdish and Iraqi left and was symbolic of the Communist Party’s approach to unity between Arabs and Kurds, serving as leader of the Iraqi party from 1964 to 1993, then of the independent Kurdish party after that.

When asked about the KCP’s relationships with other communist parties in the region who may oppose Kurdish independence, Gorran attempts to toe a diplomatic line, saying it would probably be better if I ask those parties why they take such a position. In the end, however, he says, “It is clearly related to chauvinism. This is not a communist position. It has nothing to do with Lenin’s conception of a nation’s right to be self-determining.” On the reactionary role of the United States in Kurdistan This question was wrapped up in another extremely important point that needed to be clarified, which is the relationship between Kurdistan as an oppressed nation and the role of the United States in the region. Much of the apprehension that I have often encountered in regards to the Kurdish question from leftists and those calling themselves communists is that Kurds are merely auxiliaries of U.S. imperialism in the region, and therefore their national liberation struggle is not worthy of support. But the KCP makes it clear that they are opponents of U.S. imperialism, and the party is not afraid to speak out against the machinations of Washington in the region or criticize certain decisions taken by parties or organizations they otherwise have friendly relations with. Hawre Gorran says, “The U.S. is working for its own interests all over the Middle East. It doesn’t care about the Kurdish people. For example, they opposed the 2017 independence referendum, and when the Iraqi government captured Kirkuk, an agreement was signed for oil extraction there that clearly benefits imperialism.”

Gorran says in response, “Any agreement that is made has to take people’s needs into account. This agreement offers no protection for the people. The United States and Russia are playing a role in controlling resources in the Middle East. Any force in Rojava should be prioritizing and protecting people’s interests.” On women’s liberation Perhaps the most impressive, progressive element of that struggle in northern Syria, as well as its most concrete achievement, has been the central role that women have played in it. Indeed, the image of the fearless Kurdish woman fighter has become prevalent across the world in recent years as a result. However, there is nothing necessarily new about women playing roles equal to men in the leftist movement in Kurdistan. According to Hawre Gorran, equality of women is “extremely important” to the KCP. He elaborates, saying, “It’s essential that women are not only members of the party, but that they are able to elevate themselves to be leading cadre. In our Central Committee, it is a rule that at least 25% of members need to be women.”

I ask what stands in the way of changing these backward, patriarchal relations. “The mentality of people is a big obstacle. Often, it is their interpretation of religion that makes people believe that things are naturally supposed to be this way.” On the struggle for democracy in Kurdistan If women’s rights in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq continue to be stalled, and only incremental progress has been made, then what does this say about the state of democracy in general in the region? Gorran says, “If we look at the history of any country, we can see that the democratic struggle takes a long time. We had the struggle against the Ba’athist chauvinists, then the inner-Kurdish war. Democracy has not yet reached a higher level. For instance, Massoud Barzani has no official position, yet he still remains the main point of contact for everything in the KRG. Therefore, he effectively runs everything.” He is also eager to point out that while parties such as the PUK and KDP continue the ruling family’s dominance in leadership positions, the KCP has a different idea of democratic norms. “We have changed our General Secretary four times since our party was founded in 1993. This is very different from the other parties.” This kind of non-democratic management of the major parties also has the effect of blurring the lines between the government and what should be fighting organizations of the working class, the trade unions. Gorran says that “Many unions were created here after 1991. Some are not controlled by the PUK or KDP, but some are. For example, they control the Journalists’ Union.” This was quite a revelation. It certainly doesn’t seem far-fetched to believe that the Barzani and Talabani families having this degree of influence over the union of the region’s press workers would translate into—or help to reinforce—their control over the media and dissemination of information. Gorran says that the fighting power of many unions is compromised by these relationships, thus helping maintain the impression that there is more democracy than there often is. “One union, for instance, had a demonstration at a government office. But this union is allied to the PUK. It, therefore, becomes a sort of controlled opposition.” According to Gorran, “You used to only be able to get public sector jobs by being a member of one of the two main parties. Nowadays, this is also applying to the private sector.” In December 2020, anger and frustration at the government’s corruption, nepotism, mass unemployment, and non-payment of salaries to public sector workers for several months led to a series of demonstrations across Sulaymaniyah. In the crackdown unleashed by security forces, ten people were killed. For the Communist Party, these demonstrations were certainly worthy of support, and they played a key role in amplifying the voice of the protesters and rallying to their side, even as they cautioned against the use of violence as a tactic. After nine days, however, the movement seemed to run out of steam, not least because of the harsh repression unleashed by the authorities. “After these protests, only one or two politicians resigned. This shows that we have a long way to go.” Toward a communist horizon in Kurdistan Far from being a political party that can be summed up as operating on the fringes of Iraqi Kurdistan’s social life, I found that in reality, the Kurdistan Communist Party is continuing to build upon its rich history of militant, working-class struggle. Its necessity surely appears validated by the current situation in the region, one in which the democratic struggle feels stifled, and in which the emerging opposition forces of recent years have ebbed in popularity.

I’m reminded at this point of something Hawre Gorran said as we were wrapping up the interview. Speaking about the importance of maintaining a Marxist perspective in the 21st century, he said “It’s essential that we stay true to our principles. We know that only socialism is the answer to not only Kurdistan’s problems but those of the whole world.” AuthorMarcel Cartier is a critically acclaimed hip-hop artist, journalist, and the author of two books on the Kurdish liberation movement, including 2019’s Serkeftin: A Narrative of the Rojava Revolution, which was one of the first full accounts in English of the civil and political structures set up in northern Syria after 2012. This article was republished from People's World. Archives July 2021

0 Comments

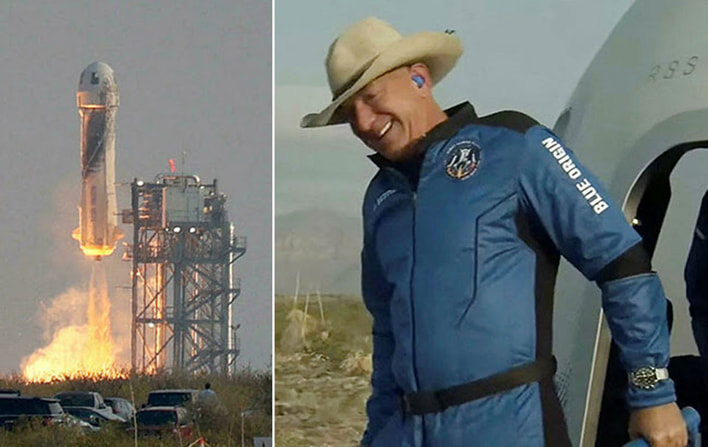

Bezos does not care that each and every one of his joy-ride space launches punches a larger hole in the Earth's ozone layer exacerbating our climate crisis. This is all about him, his money, his fame, and his super-sized ego. Jeff Bezos (the richest man in the world) successfully took his new wild west rodeo show to the edge of space and once returning to Mother Earth had the audacity to lecture us earthlings on a few things. Yahoo News reported Bezos saying: “We need to take all heavy industry, all polluting industry, and move it into space. And keep Earth as this beautiful gem of a planet that it is.” In this same interview, Bezos discussed his plans to expand Blue Origin’s space tourism business over the coming decades, a venture that has the potential to pump massive amounts of carbon and other chemicals into the atmosphere. Unlike ground-based emitters like cars or coal-powered plants, rocket emissions are expelled directly into the upper atmosphere, where they linger for years. Dr. Stuart Parkinson, Executive Director of Scientists for Global Responsibility, writes:….the fuel combination used by [Bezos is] a higher carbon fuel. Research by the University of Colorado indicates that this can damage the stratospheric ozone layer – not only leading to higher levels of damaging ultra-violet radiation reaching the Earth’s surface, but also causing a global heating effect likely to be considerably greater than that from the carbon emissions alone. And the aim of these journeys? A few minutes of zero-gravity experience and a nice view. It is hard to see this as anything more than environmental vandalism for the super-rich. As the CEO of Amazon, for years Bezos fought against company efforts to unionize, even amid credible reports of inhumane, exploitative conditions for Amazon delivery drivers and warehouse workers. He said, “I also want to thank every Amazon employee and every Amazon customer because you guys paid for all of this.” The truth is that virtually all space technology ‘research and development’ since the dawn of the space age was done by NASA and the military industrial complex. That means the taxpayers paid for it. And now when it is possible to make gobs of money from space tourism, colonization, and mining, the capitalist dominated US government is eager to privatize space operations. They don’t care what the rest of the world thinks. America, after all, is the ‘exceptional’ nation. It was during the Obama administration that a new law called Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, sometimes referred to as the Spurring Private Aerospace Competitiveness and Entrepreneurship (SPACE) Act of 2015, was signed by the president. The UK Independent reported in 2015:Much of the ownership of space is regulated by the “Outer Space Treaty”, a document that was signed by the US and Russia among other countries in the 1960s. As well as saying that the moon and other celestial objects are part of the “common heritage of mankind”, it says that exploration must be peaceful and bans countries from putting weapons on the moon and other celestial bodies. The US government has now thrown out that understanding so that it can get rid of “unnecessary regulations” and make it easier for private American companies to explore space resources commercially. While people won’t actually be able to claim the rock or “celestial body” itself, they will be able to keep everything that they mine out of it. Planetary Resources, an American company that intends to make money by mining asteroids, said that the new law was the “single greatest recognition of property rights in history”, and that it “establishes the same supportive framework that created the great economies of history, and will encourage the sustained development of space”. So Bezos was wearing the cowboy hat as a message to the world that a new ‘gold rush’ has begun in space and that it will be controlled by rich fat-cat psychopaths like him. They intend to circumvent United Nations space law like the Outer Space and Moon Treaties that state the “heavens are the province of all humankind.” Bezos does not care that each and every one of his joy-ride space launches punch a larger hole in the Earth’s ozone layer exacerbating our climate crisis. This is all about him, his money, his fame, and his super-sized ego. If we hope to survive on planet Earth and give life to future generations, then the global public must demand that space stooges like Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Richard Branson, and the rest of their ilk, are restrained and prevented from playing god. ~ Bruce Gagnon Coordinates the Global Network Against Weapons & Nuclear Power in Space. Check out our short space issues videos on our website. AuthorBruce Gagnon is the Coordinator of the Global Network Against Weapons & Nuclear Power in Space. This article was republished from People's World. Archives July 2021 7/25/2021 Serve the People: The Eradication of Extreme Poverty in China. By: TricontinentalRead NowWomen who migrated to the Wangjia community participate in local activities at the community centre in Tongren City, Guizhou Province, April 2021. These photographs were made during a trip to Guizhou Province visiting people and sites linked to China’s targeted poverty alleviation programme. The drawn lines extending on top of the images remind us of architectural sketches. Socialism, after all, is about the constant work of construction. This visual language speaks to the name of the series of publications on socialist construction that this study inaugurates. ContentsGrandma Peng Lanhua in her two-hundred-year-old home, renovated and serviced with electricity, running water, and satellite television in the village of Danyang, Guizhou Province, April 2021. Part I: Introduction ⤴Grandmother Peng Lanhua lives in a two-hundred-year-old rickety wooden house in a remote village of Guizhou Province. Born in 1935, she grew up in a China that was under Japanese occupation and entered adolescence during the Chinese Revolution. Peng is one of the few people in her community who did not want to relocate as part of the government’s poverty alleviation programme when the government designated her house unsafe to live in. Since 2013, eighty-six other households whose houses were deemed too dangerous or for whom jobs could not be generated locally were moved to a newly built community an hour’s drive away. But Peng has her reasons for not moving. She is eighty-six years-old and lives with Alzheimer’s disease. In addition to low-income insurance and a modest pension, she receives supplemental income from a new grapefruit company that leased her family’s land. The company, whose dividends are distributed to villagers like Peng as part of the national anti-poverty efforts, was established to develop the local agricultural industry. Peng’s daughter and son-in-law live next door in a two-storey house they built with government subsidies. Her children are employed. In other words, her basic needs are cared for, and relocation is voluntary. ‘We can’t force anyone to move, but we still have to provide the “three guarantees and two assurances”’, says Liu Yuanxue, the Party cadre sent to live in the village to see that every household emerges from extreme poverty. He is referring to the government poverty alleviation programme’s guarantee of safe housing, health care, and education, as well as being fed and clothed. Liu visits Peng on a monthly basis, as he does with all the households in the village. Through these visits, he comes to know the details of each person’s life. ‘The floor is too messy’, Liu says, jokingly reprimanding Peng’s daughter-in-law as he enters the large wooden house. She is also a member of the Communist Party of China. On the wall, a poster of Chairman Mao and, next to him, President Xi Jinping, pay homage to two of China’s socialist leaders who bookend the course of Peng’s life. Below their portraits sit a weathered table and a dusty terracotta water jug, an internet router flashing green beside them. A string of ethernet cables and wires stretch to different corners of the house (each house gets free internet and CCTV satellite television for three years before a subsidised rate sets in). There are energy-saving lightbulbs in each room and a satellite dish installed next to Peng’s hanging laundry. An extension of the house was built with a toilet and shower equipped with solar-heated running water, the mud floor poured over with concrete. As Lenin said, ‘Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country’. Strengthening the Party in the countryside and meeting the concrete needs of the people have been pillars in China’s fight against poverty. Liu’s visit to Peng’s house is just one everyday scene in that process. The fact that Peng has lived in this house for half a century is also a product of the Revolution; in the 1970s, during the Cultural Revolution, the house was confiscated from a rich landlord and redistributed to three poor peasant families, including Peng’s. That cadres like Liu visit her on a monthly basis, that her house has been made safe to live in through the recent renovations, and that there is internet to connect the poorest of rural villages with the world is a continuation of this revolutionary history. After all, ensuring that the country’s workers and peasants like Peng get housed, fed, clothed, and cared for is part of China’s long struggle against poverty and a fundamental stage in constructing a socialist society. The Greatest Anti-Poverty Achievement in HistoryOn 25 February 2021, the Chinese government announced that extreme poverty had been abolished in China, a country of 1.4 billion people. This historic victory is a culmination of a seven-decade-long process that began with the Chinese Revolution of 1949. The early decades of socialist construction laid the foundation that was deepened during the reform and opening-up period. During this time, 850 million Chinese people were lifted and lifted themselves out of poverty; that is to say, 70 percent of the world’s total poverty reduction took place in China. In the most recent ‘targeted’ phase that began in 2013, the Chinese government spent 1.6 trillion yuan (US$246 billion) to build 1.1 million kilometres of rural roads, bring internet access to 98 percent of the country’s poor villages, renovate homes for 25.68 million people, and build new homes for 9.6 million others. Since 2013, millions of people, state-owned and private enterprises, and broad sectors of society have been mobilised to ensure that – despite the pandemic – China’s remaining 98.99 million people from 832 counties and 128,000 villages exit absolute poverty.[1] In 2019, as China entered the last stages of its poverty eradication scheme, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres said, ‘Every time I visit China, I am stunned by the speed of change and progress. You have created one of the most dynamic economies in the world, while helping more than 800 million people to lift themselves out of poverty – the greatest anti-poverty achievement in history’.[2] While China has been fighting poverty, the rest of the world, especially the Global South, has experienced a downward turn. United Nations agencies report a great reversal in poverty elimination outside of China: in 2020, over 71 million people – most of whom are in sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia – slipped back into poverty, marking the first global poverty increase since 1998.[3] It is estimated that the economic crisis accelerated by the pandemic will drive a total of 251 million people into extreme poverty by 2030, bringing the total number to over one billion.[4] That China was successful in combatting poverty in a time of such reversal is neither a miracle nor a coincidence, but rather a testament to its socialist commitment. This stands in contrast to capitalist societies’ indifference to the needs of the poor and the working classes, whose conditions have only worsened during the pandemic. This study looks into the process through which China was able to eradicate extreme poverty as a fundamental step in constructing socialism. Based on a range of Chinese and English sources, the study is divided into five key parts: historical context, poverty alleviation theory and practice, targeted poverty alleviation, case studies, and the challenges and horizons ahead. Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research also conducted interviews with leading Chinese and international experts and made field visits to poverty alleviation sites in Guizhou Province, where the last nine counties lifted out of poverty are located. There, we visited poor villages, industrial projects, and relocation sites. We spoke with peasants, Party cadres, business owners, workers, youth, women, and elders who have been directly impacted by and have participated in the fight against poverty. Woven throughout the text, their stories are just a few among the millions who have contributed to this historic process. A mural of Mao Zedong displayed in a rural village and local ‘red tourism’ attraction in Wanshan District, Guizhou Province, April 2021. Part II: Historical Context ⤴Meeting the People’s Increasing Needs for a Better LifeMy mother has two daughters, a young son who is now working in Guangzhou, and seven grandchildren. She has worked really hard to support her three children’s educations. She herself was only able to finish the second grade at primary school and started working soon afterwards by selling vegetables, going out very early in the morning and coming home late at night. Life was really tough when I was young. We ate corn grits all the time and never had rice. Now mother is here, cooking meals for the children, buying groceries, and taking her walks now and then. We would be worried if she stayed alone in her old home. Now it’s much easier for her to go back, as it only takes two or three hours. She travels back to her old home on special occasions. Sadly, my father, who had never been here, passed away a couple of years ago. His greatest hope was to come and visit here, but he died of a brain haemorrhage. He Ying is a relocated member of the Wangjia community, where she became a Party leader. Her mother is sixty-nine years old, just three years younger than the Chinese revolution. Her lifetime traces the multigenerational struggle against poverty that the country has undertaken. Days before the official proclamation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on 1 October 1949, Chairman Mao Zedong said: ‘The Chinese people, comprising one quarter of humankind, have now stood up’.[5] China’s national liberation came after what is referred to as a ‘century of humiliation’ at the hands of European colonial powers, a bloody civil war with Nationalist forces, and fourteen years of resistance against Japanese fascism that claimed up to thirty-five million Chinese lives.[6] Internally, the Nationalist Party, warlords, and feudal landlords prioritised their class interests over the well-being of the people and the country. During this period, China would go from being the biggest global economy to one of the world’s poorest countries. Accounting for one-third of the global economy in the beginning of the nineteenth century, the country’s GDP would fall to less than 5 percent by the PRC’s founding. In 1950, only two Asian and eight African countries had lower per capita GDPs than China: Myanmar, Mongolia, Botswana, Burundi, Ethiopia, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Lesotho, Malawi, and Tanzania.[7] In other words, the PRC was the eleventh poorest nation in the world upon its founding. When the communists came into power, they were faced with the challenge of reversing the country’s long term economic and social decline, beginning with meeting the basic needs of the country’s impoverished peasants and working class. From 1949 to 1976, under Mao’s leadership, the Chinese government focused on improving the quality of life for its population, which had grown from 542 to 937 million people.[8] In the first years of this period, poverty was addressed by transforming private ownership of the means of production into public hands and redistributing land from landlords and warlords to poor peasants. Poverty, after all, is an issue of class struggle. By 1956, 90 percent of the country’s peasants had land to till, 100 million peasants were organised in agricultural cooperatives, and private industry was effectively abolished. People’s Communes organised collective ownership of the land and means of production and distributed collective wealth, enabling the agricultural surplus to be invested into industrial development and social welfare.[9] In the twenty-nine-year pre-reform period (1949-1978), China’s life expectancy increased by thirty-two years. In other words, for every year after the Revolution, more than one year was added to the life of an average Chinese person. In 1949, the country’s population was 80 percent illiterate, which in less than three decades was reduced to 16.4 percent in urban areas and 34.7 percent in rural areas; the enrolment of school-age children increased from 20 to 90 percent; and the number of hospitals tripled. The decentralisation of the health and education systems from elite urban centres to poor rural areas was key. This process included establishing middle schools for workers and peasants and dispatching millions of barefoot doctors to the countryside. Significant advances were made in women’s participation in society, from abolishing patriarchal marriage customs to increasing access to education, health care, and childcare.[10] From 1952 to 1977, the average annual industrial output growth rate was 11.3 percent.[11] In terms of productive capacity and technological development, China went from not being able to manufacture a car domestically in 1949 to launching its first satellite into outer space in 1970. The Dongfanghong satellite (meaning ‘The East is Red’) played the eponymous revolutionary song on loop while in orbit for twenty-eight days.[12] The industrial, economic, and social gains in the transition to socialism under Mao formed the foundation of the post-1978 period. By the 1970s, it became clear that China’s economy required an infusion of technology and capital, and that it needed to break its isolation from the world market. As China’s leader Deng Xiaoping later wrote, ‘Pauperism is not socialism, still less communism’.[13] The government introduced a range of economic reforms, including opening the economy to the world market, but – because China remained a socialist country – the public sector remained dominant and free of foreign control. During this period, China’s economy grew at a sustained pace never before seen in human history. Between 1978 and 2017, China’s economy expanded at an average rate of 9.5 percent per year, growing in size by almost thirty-five times.[14] Economic growth, however, is not an end in itself, but a means to improve the lives of the people. Between 1978 and 2011, the number of people living in absolute poverty dropped from 770 million (80 percent of the population) to 122 million (9.1 percent), measured by setting the poverty line at 2,300 yuan per year.[15] Pursuing rapid economic growth, however, came with great environmental and social costs. Mass migration to the cities heightened the rural-urban disparity, and the focus on eastern coastal industries left the western and central regions heavily underdeveloped. According to the World Bank, China’s Gini coefficient (a measure of inequality based on income) increased from 29 percent in 1981, peaking at 49 percent in 2007, and falling to 47 percent in 2012[16]. Socially, this period produced unequal access to public services such as pensions, social insurance, education, and health care. Environmentally, rapid development took a toll on the country’s air, water, and land. It is not surprising that addressing inequality became a principal task under President Xi (2013-present). At the nineteenth National Congress of the CPC in 2017, the twice-a-decade event that determines the national policy goals and election of top leadership, Xi spoke of the new era of socialism and, with it, the evolution of the principal contradiction faced by Chinese society: As socialism with Chinese characteristics has entered a new era, the principal contradiction facing Chinese society has evolved. What we now face is the contradiction between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life. China has seen the basic needs of over a billion people met, has basically made it possible for people to live decent lives, and will soon bring the building of a moderately prosperous society to a successful completion. The needs to be met for the people to live better lives are increasingly broad. Not only have their material and cultural needs grown; their demands for democracy, rule of law, fairness and justice, security, and a better environment are increasing. At the same time, China’s overall productive forces have significantly improved and in many areas our production capacity leads the world. The more prominent problem is that our development is unbalanced and inadequate. This has become the main constraining factor in meeting the people’s increasing needs for a better life.[17] The reform and opening-up period is therefore seen as the pre-condition for building a modern socialist country. It is during this period when two of the three official strategic goals were achieved, ensuring that the people are have a decent standard of life and that their basic needs are met. Continuing the work of poverty alleviation and ensuring that poor people enter a ‘moderately prosperous society’ (xiaokang) in the rest of the country is a final step in this period. In the years since Xi’s speech, China has mobilised its people – specifically the poor themselves – as well as the government and the market to eliminate extreme poverty, marking a key phase in the transition to socialism. Peasant workers till the land in an organic bamboo fungus company, which was established to help lift Longmenao, a village that is officially registered as poor, out of poverty in Wanshan District, Guizhou Province, April 2021. Part III: Poverty Alleviation Theory and Practice ⤴One Income, Two Assurances, and Three Guarantees China’s elimination of extreme poverty comes a decade ahead of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which set ‘eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including extreme poverty’ as its principal target.[18] While millions of Chinese people emerged from poverty during the phase of rapid economic growth, economics itself cannot explain this achievement. For this study, we spoke with Justin Lin Yifu, former chief economist of the World Bank (the first from the Global South) and founder of New Structural Economics. Lin is also a standing committee member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Congress National Committee and a professor at Peking University. Lin classifies two primary approaches to poverty reduction, which he calls ‘blood transfusion’ and ‘blood generation’. The former – a preferred model in Western economies – is characterised by humanitarian aid or welfare mechanisms to guarantee that basic needs are met. Meanwhile, the latter describes development-oriented poverty alleviation that creates employment and increases the incomes of the poor. These two approaches alone, however, were unable to eliminate poverty in the poorest pockets of China. According to Lin, ‘In areas that are short of natural resources, far away from the market, and have poor transportation and infrastructure, such as the “Three Regions and Three Prefectures”,[19] targeted assistance is needed’. The comprehensive concept of targeted poverty alleviation – officially implemented in 2015, concluding at the end of 2020 – was developed and innovated based on decades of domestic and international experiences. ‘China’s poverty alleviation’, Lin summarises, ‘is a growth-driven, government-led strategy that combines social support and the peasants’ own effort, features the “blood generating” or development-oriented pattern, and guarantees basic needs through social security’. Stressing the role of government leadership, he says: ‘In contrast to the rest of the world, the Chinese government has played a crucial part. Poverty eradication would not have been achieved merely through the role of the market had the government not paid great attention to the issue of the poor people’. In other words, a combination of the ‘visible’ and ‘invisible hand’, together with the mobilisation of broad sectors of society, was the hallmark of China’s poverty alleviation in this ‘targeted’ phase. China’s Targeted Poverty Alleviation (TPA) programme can be summarised by one slogan: one income, two assurances, and three guarantees. Regarding income, the international poverty line is set by the World Bank at US$1.90 per day, measured in 2011 prices and based on the average poverty line of the world’s fifteen poorest countries. China’s poverty line was last raised to 2,300 yuan per year in 2011 (set at 2010 prices), which represents US$2.30 per day when adjusted to Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), exceeding the World Bank standard. Adjusted to 2020 prices, the annual minimum income is 4,000 yuan, while the per capita income under the targeted alleviation programme of 10,740 yuan per year is much higher.[20] Understanding that poverty cannot be addressed by income distribution alone, China’s programme takes on a multidimensional approach. First theorised by Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen, the concept of multidimensional poverty looks at the intersecting and complex factors associated with poverty that are not accounted for just by measuring income. Elaborating upon Sen’s work, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative adopted the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) in 2010, measuring ten indicators across the three dimensions of health, education, and basic infrastructural services. Their 2020 report, launched a decade after MPI’s adoption and a decade before the Sustainable Development Goals’ (SDG) deadline, found that 1.3 billion people, or 22 percent of the world’s population, live in multidimensional poverty.[21] In comparison, according to the US$1.90-a-day poverty line, 689 million people – or 9.2 percent of the global population – lived in extreme poverty in 2017, prior to the pandemic.[22] In addition to a minimum income, China’s poverty alleviation programme ensures that five other indicators are met: the ‘two assurances’ of food and clothing and the ‘three guarantees’ of basic medical services, safe housing with drinking water and electricity, and free and compulsory education, which in China is for nine years. We spoke with Wang Sangui, dean of the National Poverty Alleviation Research Institute of Renmin University about the relationship between China’s indicators and the MPI framework: ‘Multidimensional Poverty is only seen as a research approach’, he said, ‘and so far has not been adopted by any country to measure the size of the poor populations at the national level because of its great complexity’. However, by including the five key indicators, he adds, ‘In fact, China has followed a multidimensional approach in poverty eradication’. As an expert advisor to the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development, Wang helped develop the standards for China’s programme. ‘How do you classify drinking water as safe? First, the basic requirement is that there must be no shortages in water supply. Second, the source of water must not be too far, no more than twenty minutes round-trip for water retrieval. Last, the water quality must be safe, without any harmful substances. We require test reports that confirm the water quality is safe. Only then can we say that the standard is met’. First Secretary Liu Yuanxue speaks with a local villager during routine home visits in the village of Danyang, Wanshan District, Guizhou Province, April 2021. Part IV: Targeted Poverty Alleviation ⤴Don’t Use a Grenade to Blast a Flea Targeted poverty alleviation, also known as precise poverty alleviation, was introduced for the first time during President Xi’s visit to Shibadong village in Hunan Province in November 2013. ‘Don’t use a grenade to blast a flea’, Xi advised the local government on how to address the root causes of poverty. Instead, he said, act as an embroiderer approaching an intricate design. This approach was implemented as the government strategy in 2015, guided by four questions: Who should be lifted out of poverty? Who carries out the work? What measures need to be taken to address poverty? How can evaluations be done to ensure that people remain out of poverty? Defining Poverty: Who Gets Lifted? On 28 August 2018, I came to Danyang, whose Party organisation was considered ‘weak and loose’ and whose work had not been pushed hard enough, which was why I was sent by the higher-level authorities to strengthen the building of the organisation. The organisation gave me a brief report about the villagers at first, and I started by touching base with the people to find out which households were the targets of poverty alleviation. Otherwise, the work wouldn’t be conducted properly. To get closer to the people, I had to understand human nature well […] The local people were poor for many reasons, including water shortages, low crop yields, diseases, disabilities, and the lack of education of children. Their problems and conflicts had been passed from generation to generation. Knowing who the poor are in a country of 1.4 billion people is an enormous undertaking. Recognising the limitations of a sampled-data statistical method, China moved towards a household identification system, which means getting to know every single poor person in the country, their conditions, and their needs. This was done through a combination of sending people to the villages, practising grassroots democracy, and deploying digital technologies. In 2014, 800,000 Party cadres were organised to visit and survey every household across the country, identifying 89.62 million poor people in 29.48 million households and 128,000 villages. More than two million people were then tasked to verify the data, later removing inaccurately identified cases and adding new ones.[23] While income is the primary deciding factor, housing, education, and health are also taken into consideration when listing a ‘poverty-stricken household’. Village committees, township governments, and the villagers themselves are mobilised to assess the status of each household. Public democratic appraisal meetings, for example, are held to facilitate discussions among community members about each family’s situation and whether they should be removed from or added to the poverty registration list.[24] This on-the-ground process was paired with the creation of an advanced information and management system, touching on all parts of the poverty alleviation process across the country. Big data is used to monitor the situation of each of the nearly 100 million individuals, facilitate information flow between governmental departments, and identify important poverty trends and causes.[25] Mobilising the people and gaining public support are at the heart of the effort to carry out this work. Mobilisation: Who Does the Lifting? ⤴Move Amongst the People as a Fish Swims in the Sea Record of Visit, 10 June 2019: Today I received a call from He Guoqiang. He said a door lock [in] his resettlement flat was broken. I went to his home and helped him contact the property management team and the construction crew for repairs. I took this opportunity to teach him to exercise his rights as a homeowner and to contact the property management and construction crew. He Guoqiang said the next time he encounters such a problem, he [will] know how to solve it.[26] There is no organisation without the organisers. As of June 2021, the CPC has more than 95.1 million members – 27.45 million of whom are women – and 4.9 million primary level Party organisations, which includes villagers’ committees, public institutions, government-affiliated organs and enterprises, and social organisations.[27] If the CPC were a country, it would be the sixteenth most populous in the world. The targeted phase of poverty alleviation required building relationships and trust between the Party and the people in the countryside as well as strengthening Party organisation at the grassroots level. Party secretaries are assigned to oversee the task of poverty alleviation across five levels of government, from the province, city, county, and township, down to the village. Most notably, three million carefully selected cadres were dispatched to poor villages, forming 255,000 teams that reside there.[28] Living in humble conditions for generally one to three years at a time, the teams worked alongside poor peasants, local officials, and volunteers until each household was lifted out of poverty. In this process, many cadres were unable to return home to visit families for long stretches of time; some fell ill in the harsh natural conditions of rural areas and more than 1,800 Party members and officials lost their lives in the fight against poverty.[29] The first teams were dispatched in 2013; by 2015, all poor villages had a resident team, and every poor household had an assigned cadre to help in the process of being lifted, and more importantly, of lifting themselves out of poverty.[30] At the end of 2020, the goal of eliminating extreme poverty was reached. Liu Yuanxu, a forty-seven-year-old man with a daughter in her senior year of high school, is among the Party secretaries who were sent in 2018 to Danyang, a village of 2,855 people in the southwestern province of Guizhou. Liu describes arriving in Danyang, where he does not speak the local dialect, and where 137 of the village’s 805 households were designated as poor. He was one of 52 cadres assigned to the village, each with different responsibilities. He told us about his day-to-day work: I was responsible for five poor households, but it is now for four, since one person died. Back then I visited every family on an electric bike and took care of everything for them. I kept in touch with the young people on WeChat and the elders by phone. They could call me for anything. I went to every villager group to investigate who was nice and who was difficult. I’ve resolved problems through drinks and talks with the villagers who now have a very good relationship with me. Now the government maintains a register of poor households, marginal households, and key households. Digital tools help the government know when people get sick or if those who can work are employed. We also visit the villagers every month to better understand the reality of their situation. Unlike models that rely heavily on non-governmental organisations and international assistance, China’s poverty alleviation programme draws its strength from mobilising its citizens. Cadres like Liu are an essential bridge between implementing government policy and understanding the concrete conditions and demands of the people. The more than ten million cadres and officials who have mobilised in the countryside have been essential in building public support for and confidence in the Party and the government. In 2020, Harvard University published a study, Understanding CCP Resilience: Surveying Chinese Public Opinion Through Time, for which they interviewed 31,000 urban and rural residents between 2003 and 2016 about their support for the CPC.[31] During this period, Chinese citizens’ satisfaction with their government increased across the board from 86.1 percent to 93.1 percent. The greatest increase in government satisfaction was seen in the rural township-level areas, which increased from 43.6 percent approval to 70.2 percent approval, particularly among lowest-income residents and those from the poorer inland areas. This growing support stems from the increased accessibility and quality of health care, education, and social services, as well as from the improved responsiveness and effectiveness of local government officials. Though the study ended in 2016 before the campaign’s completion, the poverty alleviation programme and the government’s effective response to COVID-19 have continued to build public support.[32] Shortly after Wuhan emerged from the COVID-19 lockdown, York University Professor Cary Woo led a survey of 19,816 people across 31 provinces and administrative regions. Published in the Washington Post, the study found that 49 percent of respondents became more trusting of the government following its response to the pandemic, and overall trust increased to 98 percent at the national level and 91 percent at the township level.[33] Eliminating poverty and containing the pandemic can be seen as two major victories of China and its people in 2020.

|

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed