|

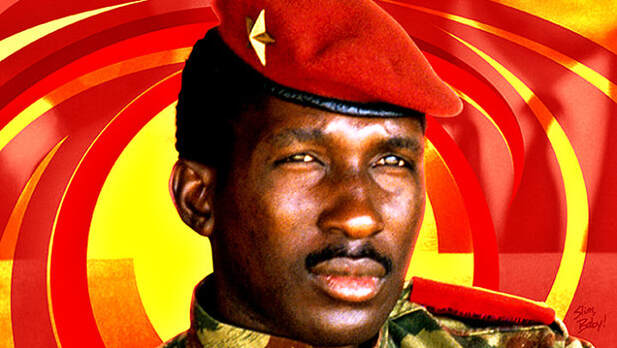

With the bombshell announcement that Burkina Faso’s longtime strongman, Blaise Compaore, will finally be tried for the murder of Thomas Sankara[1], I want to take this opportunity to bring back a particular time in history when the world could have chosen to build a new international order. In 1984, Thomas Sankara spoke in front of the UN General Assembly as the leader of the newly christened nation of Burkina Faso. There at the center of global capital, he gave his most visionary speech of the world he wanted to build, a world where nations are not economically shackled to their former colonizers, where the struggles of the working class in the first world are seen as the same as newly liberated nations struggling to determine their own destiny. The international order of western capital extracting wealth from the workers of the global south, hollowing out the planet for profit, and endless wars that Sankara sought to dismantle has only become worse. Perhaps it's time to look at the world that Thomas Sankara wanted us to fight for. Imperialism Is On Your Plate“Now our eyes have been opened to the class struggle and there will be no more blows dealt against us. It must be proclaimed that there will be no salvation for our peoples unless we turn our backs completely on all the [economic] models that all the charlatans of that type have tried to sell us for 20 years.”[2] People remember Sankara for his many stellar achievements: vaccinating 2 million kids; planting 10 million trees; and achieving national food self-sufficiency, to name a few.[3] However, it is crucial we remember that Sankara saw these massive public projects as more than just a series of generous social programs, but instead as a step towards national liberation. The 1950s and ‘60s saw a wave of African nations gain independence from Europe’s empires. However, these new post-colonial leaders soon realized that political independence did not necessarily mean economic independence. Most European colonies were deprived of the means to invest in a sizable manufacturing industry, let alone an industrial base, in order to act as a cheap source of commodities for Europe’s industrial economy. Thus the first task for many post-colonial nations was to modernize their economies, which they found to be possible only by using loans and skilled labor from the empires they sought independence from. European nations and the global north in general used debt to force post-colonial nations to maintain the same economic relationship that existed during the colonial era. Some have called this system “neo-colonialism,” others, such as Vijay Prashad, maintain that it’s the same imperialism that Lenin railed against in 1917. In Burkina Faso, one of the most overt examples of neo-colonialism strangling the Burkinabe’s desire for self-determination was foreign aid, an institution that continues to plague the African continent. Sankara resented how foreign charities never offered their aid without strings attached. Burkinabes found it humiliating, that in a mostly agrarian nation, they were forced to depend on the global north for food. Sankara’s drive for food self sufficiency was driven partly by a desire to do away with the west’s paternalistic attitude towards the Burkinabe. Sankara stated bluntly, “Some people ask me, “but where is imperialism?” Just look into your plates where you eat.”[4] This is why Sankara’s lesser-known project of resurrecting the traditional dress, the Faso Dan Fani, might be his most revolutionary. Like food, Burkina Faso imported much of it’s garments, western clothing was especially popular among the bureaucratic class. Sankara’s government instituted a national campaign to shift from foreign made clothes to manufacturing traditional Burkinabe clothes through female-led cooperatives that sourced their cotton from Burkinabe farmers, breaking one of the biggest economic taboos--that modernization required liquefying the peasantry to produce a cheap surplus of commodities and labor. Previous modernization projects in the continent typically came at the violent expense of local communities. One of the most notorious examples was the construction of the Kariba Dam, a 420 foot tall hydroelectric dam that displaced 57,000 Tonga people in modern day Zambia and Zimbabwe. Sankara did not want to replace the foreign capitalist with a domestic one, and he proved that modernization can benefit the existing farming population and workers in newly emerging manufacturing industries. The campaign to revive the Faso Dan Fani was an immensely successful one, going from a nearly non-existent light industry to generating a million dollars in revenue by 1987.[5] While the Faso Dan Fani campaign was not necessarily an industrial project, it was crucial to diverting cotton from low income export to an income generating domestic industry with an indigenous consumer base. If the Sankaran revolution was not cut short after four years, the Faso Dan Fani campaign could have evolved into a thriving textile industry on par with modern day Vietnam. We Feel On Our Cheek Every Blow Struck Against Every Other Man In The World“I speak not only on behalf of Burkina Faso… but also on behalf of all those who suffer… those millions of human beings who are in ghettos because their skin is black… those [indigenous Americans] who have been massacred, trampled on and… confined to reservations… women throughout the entire world who suffer from a system of exploitation imposed on them by men… I wish to stand side by side with the peoples of Afghanistan and Ireland, the peoples of Grenada and East Timor. We wish to enjoy the inheritance of all the revolutions of the world.”[6] Sankara’s vision reveals that nationalism can transcend nations itself. When he came to power, Burkina Faso still maintained its colonial name, Upper Volta. Sankara invented the name Burkina Faso, which translates to “the Land of the Upright People,” by combining the languages of three main ethnic groups in the country. Sankara himself was Silma-Mossi, a social minority, a fact that Compaore, who was a member of the larger Mossi population, would unfortunately exploit in 1987.[7] Today, nationalism is often associated with ethnonationalist projects, such as Israeli apartheid or American nativism, but to Sankara and many anti-colonial leaders, nationalism was seen as a collective project for the self determination of all oppressed peoples. Sankara truly understood the internationalist element of self determination. In his speech to the UN, Sankara does not simply declare solidarity with liberation movements abroad; he declares that they are fundamentally the same struggle. Sankara connects the struggles of the black ghettos in the US to the Palestinians’ struggle against Israeli occupation to Black Africans’ struggle against the apartheid regime, by framingt each struggle through the neocolonial system.[8] His speech was an elaboration of his Third World politics. While Third Worldism is often vulgarly interpreted as denying the working class in the global north as part of the international proletariat, the third world movement at its height was far from promoting this idea. Right before he gave his speech to the UN, Sankara visited Harlem, where he told a crowd of several hundred African Americans that “our White House is Black Harlem.”[9] Sankara was not an outlier on this front. Revolutionary socialist organizations in the United States, such as the Black Panther Party, Gidra, and CAVAS, used Third Worldist analysis to identify issues unique to the communities they organized.[10] Sankara did not see the working class of the developed world as enemies, but correctly concluded that the liberation of at least some segments of the working and underclass in the global north was fundamental to ending US imperialism and global capitalism. Sankara also did not tolerate “the internationalism of fools. He viewed corruption and abuse committed by post-colonial leaders as maintaining the old colonial system. During his brief tenure, Burkina Faso became a haven for foreign activists and dissidents. In 1987, Burkina Faso hosted the Bambata Forum, where Pan African and anti-apartheid activists discussed how they can mobilize support for SWAPO and the ANC, which were then engaged in armed struggle in Namibia and South Africa.[11] Burkina Faso’s active foreign policy terrified their former French overlords, who in 1986 brought Jacques Foccart back into government. Foccart, also known as “Mister Africa” for his role in maintaining France’s colonial regime, used his former colonial network to rally allied African leaders to isolate the spread of Burkina Faso’s revolutionary ideas. Sankara had no qualms publicly calling out post colonial leaders in the Francosphere who were willing to maintain the colonial status quo. One of Foccart’s allies, Houphouët-Boigny, established contact with a high ranking Burkinabe officer who was wary of Sankara’s aggressive anti-corruption drive. That officer was Blaise Compaore.[12] Kill Me And Millions Of Sankaras Will Be BornThere are two lessons we can learn from Thomas Sankara’s vision for a “new international economic order.” The first is that anti-imperialism must be anti-capitalist and vice versa. Using the same means that colonial powers and corporations used to exploit the working and oppressed classes will only recreate those same relationships. The greatest threat Sankara posed to global capital was not his support for Cuba or SWAPO, but his willingness to launch modernizing programs on behalf and not at the expense of Burkina Faso’s peasantry and working class. Food self-sufficiency, textile cooperatives, and mass vaccinations threatened to expose an alternative to the neocolonial system of debt and foreign aid that wealthy nations are all too eager to maintain. Sankara’s premonitions would tragically turn out to be true. By 1987, Foccart had succeeded in isolating Burkina Faso from most African nations in the Francosphere, and overzealous and opportunistic purges by the Committees in Defense of the Revolution (CDR) alienated them from the communities they sought to represent, which would eventually culminate in Blaise Compaore seizing power in what was most likely a French-backed coup. Compaore would reverse most of Sankara’s reforms, leaving the country in much the same position it was in 1983. Today, Burkina Faso faces an ecological crisis of desertification, millions struggle with food insecurity, and the people are once again heavily dependent on foreign aid.[13] However, even with a three decades long attempt to erase his memory, Sankara’s legacy refuses to die. During the 2014 uprising that finally overthrew Compaore’s regime, protesters defiantly held up portraits of Sankara, who had become a popular symbol among a generation that was not even alive to witness Sankara’s revolution.[14] What we should all take away from Sankara’s revolutionary four years is that the struggle for self-determination must be an international one. Sankara understood Burkina Faso’s independence could not be possible if the system that exploits the working class in both the global north and south. Sankara envisioned a “new international order” because he believed that was the only way to preserve and expand Burkina Faso’s achievements from the neocolonial counterrevolution. Now that Thomas Sankara is back in the spotlight, one way we can preserve his public memory is to show that his vision of the world can still become a reality.

Bibliography Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

AuthorJay is a Korean-American, who has lived in South Korea, Vietnam, and the Midwest and East Coast of the United States. While studying in Iowa, he became a student organizer for a statewide organization fighting for Free College for All and co-founded the local Students for Bernie chapter, which is now a chapter of the Young Democratic Socialists of America. Jay is also one of the hosts of Red Star Over Asia, a podcast which interviews organizers, academics, and journalists on politics in the Asian continent from a socialist perspective. Archives May 2021

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

About the Midwestern Marx Youth LeagueThe Midwestern Marx Youth League (MMYL) was created to allow comrades in undergraduate or below to publish their work as they continue to develop both writing skills and knowledge of socialist and communist studies. Due to our unexpected popularity on Tik Tok, many young authors have approached us hoping to publish their work. We believe the most productive way to use this platform in a youth inclusive manner would be to form the youth league. This will give our young writers a platform to develop their writing and to discuss theory, history, and campus organizational affairs. The youth league will also be working with the editorial board to ensure theoretical development. If you are interested in joining the youth league please visit the submissions section for more information on how to contact us!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed