|

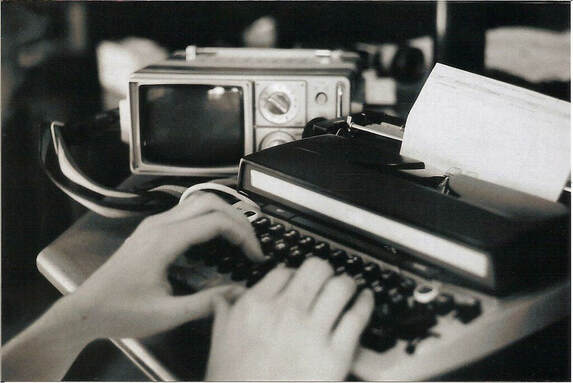

6/24/2021 The Crest of the High Wave: Radical Students and the Underground Press at UNI. By: Ty KralRead Now“History is hard to know, because of all the hired bullshit, but even without being sure of “history” it seems entirely reasonable to think that every now and then the energy of a whole generation comes to a head in a long fine flash, for reasons that nobody really understands at the time—and which never explain, in retrospect, what actually happened...You could strike sparks anywhere. There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning. . . And that, I think, was the handle—that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil. Not in any mean or military sense; we didn’t need that. Our energy would simply prevail. There was no point in fighting—on our side or theirs. We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave. . . So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark—that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.” The story of UNI’s underground press and its student staff stands as a microcosm of the burgeoning political and social changes seen in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. At the University of Northern Iowa, small-town Iowa students and working-class youth became the messengers of the era’s radical politics and student action. At the national level, the United States of the 1960s and early-1970s was a time of massive social upheaval marked by the conflict in Vietnam, social/political movements, and the rise of the “freaks” and the New-Left. We have no shortage of books seeking to explain why so many American youths grew restless and dissatisfied with their country, and why so many turned to left-wing politics throughout the decade. Whether they’re viewed through a liberal, conservative, or socialist lens, the Sixties (the all encompassed decade) is a topic that is still fiercely debated today. Depending on the researcher or daytime television wonk, the Sixties stands as a watershed moment in American culture. But the counterculture of these youth rebels and “freaks” is most often attributed to the coastal cities and major universities in the USA. Areas such as the Midwest are often forgotten about or brushed aside by the more “exciting” locations such as San Francisco and Berkeley. So, it is my goal with this article to nullify those notions and discuss the radicalism that was present at UNI. The counterculture of the Sixties was a diverse and expansive list of comedy, music, drugs, and writing. One facet of this massive ocean of movements was the rise of the so-called underground press in cities such as New York and San Francisco, especially at the universities. For those on the New-Left, underground newspapers were the alternative to the dismissive critiques of the mainstream media and provided their readership with a vulgar, passionate look into the cultures in which they lived. In 1965, the New Left could only claim 5 such newspapers, mostly in big cities, but within a few years, several hundred newspapers were in circulation with a combined readership in the millions.[1] Underground newspapers, according to Abbie Hoffman, were the “... most important institution in our lives... It keeps tuned in on what's going on in the community and around the world. Values, myths, symbols, and all the trappings of our culture are determined to a large extent by the underground press.”[2] The story of the underground press at the University of Northern Iowa begins with a newspaper called the Campus Underground in 1968. The Campus Underground was conceived by a publisher named Doug Warrington who aspired to make it a nationally syndicated newspaper. Its office was located 401-⅓ Main Street, Cedar Falls, Iowa, presently the location of the Voodoo Club Bar. In the beginning, the paper had 30 representatives from colleges and universities across the state who contributed articles and tips. The paper’s editor, Bruce “Bruno” Niceswanger, was a master’s student at UNI who was recruited by Doug Warrington after a search at all three state universities in Iowa.[3] The first issue was released on October 21, 1968, In this issue, they discussed segregation at Loras College, draft board protests across the state, and a feature-length editorial from David Quegg on his experiences among the protesting and riots at the Chicago DNC Convention of 1968 that previous summer. But after a few issues, a lack of resources and communication led to less participation from other campuses, and Cedar Falls became its primary audience.[4] While not a major success on campus, the paper gained a dedicated following as it grew more progressive and bolder with each issue. That was until the late fall of 1968, in which a review of Norman Mailer’s “Fall of Miami and the Siege of Chicago” by Carl Childress, a controversial UNI English professor, used a quote that contained a certain four-letter word. After this, the local printers refused to print any further issues unless the obscenity was removed, especially as the pressure of printing an underground newspaper grew.[5] The staff of Campus Underground was then forced to build their own light tables and lay out the paper themselves. After this, the paper began to face financial woes as the costs were just barely met from each issue to the next. By the spring of 1969, the staff began to print notices informing the readers about their financial situation while asking for donations.[6] According to a 1971 article from the Northern Iowan, at one point the staff was short $100 of the printer’s fee and frantically rushed around the Hub looking for donations until they finally received the necessary funds.[7] The last Campus Underground came out on March 10, 1969, due to a combination of financial problems, student disinterest in politics, and everyone going home for the summer. But this was far from the end of the underground presses run at UNI. The summer of 1969 saw Woodstock and the birth of Abbie Hoffman’s “Woodstock Nation”. This saw the blossoming of the cliché Sixties counterculture that we know today. By that fall, scores of “freaks”, or hippies, began to arrive at UNI, and with them came the rise of more radical elements such as members of the New Left. With this new wave came the arrival of the rebranded Campus Underground, now named the New Prairie Primer. Edited again by Bruno Niceswanger, the paper was assisted by the dedicated core group of Dave Quegg, Peg Wherry, Jean Seeland, and Gary Hoff. The New Prairie Primer, which I’ll refer to as the Primer from here on out, served as the epitome of this new spirit on campus. The first volume of the Primer Released on October 4, 1969, with a several page long expose by Bruno on his and David Quegg’s experiences at Woodstock titled “Going Up to Meat County.” This article proved to be very popular among UNI students, and it helped set the mood for future iterations of the paper with its quick wit, vulgarity and Hunter S. Thompson style prose and reporting. Following the success of their first issue, the Primer had received enough donations to print thousands of copies for their second edition, a free issue about the Vietnam War to coincide with the events of the STOP Vietnam War Moratorium across the state.[8] This issue contained stories from draft dodgers across the state, including a UNI student named Dick Simpson who explained why he refused induction into the armed services. It was also the first publication anywhere in Iowa to list all the state’s war dead.[9] This issue also showed a great deal of cooperation among various statewide church ministries with the radical left and anti-war hippies in the anti-war movement. But this seemingly unlikely coalition produced results unlike that seen anywhere else in Cedar Falls. The previous 1968 moratorium had brought out only 300 marchers, but by the moratorium on October 15, 1969, nearly 2,000 marchers flooded the UNI campus.[10] But this relationship also drew some ire from the community at large, especially as the Primer’s office was in the Bethany House on College Hill, where the Primer had special arrangements with the United Christian Ministry to use their property.[11] One chief critic of this relationship was a cantankerous, editor of the Waterloo Daily Courier named Bill Severin, also known as the Iron Duke. On the front page of the October 12th issue, the Iron Duke stated, “I have no quarrel with Niceswanger, Quegg, et all, or their right to publish a radical leftwing newspaper. But they and the United Christian Ministry would seem to make strange bedfellows.”[12] In response, the Primer blew the incident out of proportion with a smug, tongue-in-cheek center spread titled, “Primer Staff Bewildered, Hurt”, featuring their high school pictures and squeaky clean, cliché records as small-town Iowan youth along with their own reactions to the Iron Duke’s accusations.[13] This incident was a boon to the Primer’s sales and cemented the Primer’s tone for the rest of the year as a humorous, yet informative publication on campus counterculture. The Primer’s first run was an array of everything from local music reviews and interviews with Waterloo civil rights activists. Having shifted their focus from national news in the Campus Underground to local coverage, the contents of the Primer give an interesting look into the culture of the Cedar Valley during this time. Of course, one of the most important issues on campus at the time was that of drugs. The Primer featured tongue in cheek critiques of the local CFPD “Narcs” and the pearl-clutching of the more conservative Cedar Falls residents. In one such issue the Primer covered a community symposium on the issue of recreational drug use in the Cedar Valley. In response to the symposium, the Primer printed tutorials on how to make your own joints and listed the local street prices of dope, hash, and LSD at the time.[14] One informative, and fascinating article from this period was an interview conducted by the Primer’s own Bruno Nicewanger and their secretary Marsha Petersen titled “3 Viet Vets Rap on the War”.[15] Released with the fourth issue in November 1969, the Primer spoke with three UNI students that had served in Vietnam about why they became involved with the anti-war movement after their time overseas. In retrospect, what made this article fascinating is that the interviewees represent what I deem to be a decent overall representation of Iowan’s backgrounds at the time. Tony Ogden was a 24-year-old white male from Sanborn, Iowa, a town in Northwestern, Iowa. Dave Sessions was a 28-year-old white male from the medium-sized industrial town of Mason City, Iowa. Sam Dell was a 22-year-old African American male who was born in Phillip, Mississippi, but had grown up in Waterloo, in eastern Iowa. While not a full cross section of Iowa’s socioeconomic makeup, these three men represent facets of Iowa’s urban and rural population who converged on Iowa’s campuses during this period of cultural and political turmoil. In summary, all three guys described their experiences overseas, their backgrounds, and their journey towards realizing the atrocities and injustices happening in Vietnam. Tony described the brutality he saw unleashed upon the Vietnamese people he came close to, Sam talked of the racism that followed the military overseas, and Sessions spoke of the bureaucratic apathy towards the death and destruction being perpetuated by armed forces. As such, each man's experiences caused them to question their values and ideological frameworks, driving them towards becoming radically against a system they saw as needlessly unjust and cruel. A passage that stood out when reading this interview was from its final page, which saw all three men ruminating on the meaning of the “American tradition” and the contradictions they saw during their service. As Tony put it, “Seeing marines kneeling within sight of a pile of bodies having a chaplain cram wafers down their throats, under a cross.” While there are plenty of sections one could discuss from these interviews in the Primer, I see this insight into these three young men as a poignant look into the mindset of the emerging student radicals in the United States. But I have also not yet been so clear as what constitutes a student radical currently. And in sincerest sense I have struggled to find a definition insofar as who “they” were. In 2019, even as much then, the term “student radical” has many different connotations depending on who you ask. For the most part, a “student radical” is usually considered to be someone who holds left wing values and belongs to various flavors along the left-wing spectrum. To the politically illiterate, this would mean anyone to the left of the center right or is a “liberal”, but I digress. While a whole paper can be made on the distinction, a radical can be most definitely defined as an individual who opposes the status-quo and calls for a new system of governance and the distribution of resources. In the era of the Primer, as Vietnam raged and COINTELPRO lurked in the shadows, “student radicals” were a hodge podge of nondenominational leftists, middle-class liberals, and the “flower power” freaks. Much like discourse in the vague progressive leanings of today, the ‘60s were a ripe era of barraging liberals and infighting amongst different leftist ideological sects. However, for the most part, UNI’s left-wing and liberals found somewhat common ground in the anti-war movement and demands for more succinct student rights on campus. As is, the Primer got an uptick in sales due to the pearl-clutching of local Cedar-Loo residents after allying with the United Campus Ministries in October of ‘69. And as further articles prove within the Primer, Cedar-Loo was not that far off from the rest of the United States. Labor disputes, gentrification, environmental pollution, and racial tensions were proliferating in Waterloo. Like Joker's duality of man in Full Metal Jacket, Waterloo, Iowa, has had a tumultuous history with segregation. In the fall of 1968 these issues, and industry layoffs, led to instances of rioting in select areas of Waterloo.[16] Other concerns at the time included pollution being released by the John Deere Company and Chamberlain Manufacturing Co. that was potentially contaminating the Cedar River. The Primer then served as a repository, or even a messenger, of these causes that were not often covered by the mainstream media in the community. In a special issue about ecology, the Primer advertised events from an environmental group called SOMETHING, deriding the local tv station for passing environmental pollution onto the individuals during a special sponsored by John Deere and Chamberlain Co.[17] The Primer also teamed up with the Grinnell based-paper the High and Mighty to co-author the so-titled “Military-Industrial Complex” and Iowa’s role in the US war machine, in which they listed the major Iowa companies with defense contracts, including the amount of the contract and what products they produced for the military. Chamberlain Co. of Waterloo was a company that was directly targeted by the Primer due to their production of ammunition for the war movement. But of course, the Primer did not neglect campus issues, especially as they covered the Spring 1970 student government elections in which the Primer backed Students Rights Party participated. However, after suffering a defeat, the Primer declared a so-called “revolutionary student government” on campus which was coordinated by UNI students Al Woods, Sam Dell, and Tony Ogden.[18] By this time, Bruno stepped down as editor to form a collective editorship with everyone on the staff, in which the Primer did its part to become a forum for those who wanted to organize on campus. Among other issues, the Primer waged an aggressive campaign against the Dean Voldseth, Dean of Students, in the leadup to the potential referendum of 1970. The Primer, for several issues, was inscribed with the back-page message of “Dean Voldseth is alive and well in Cedar Falls--Still.” This campaign fizzled out once the student senate was unable to override Student President Mike Conlee’s veto against the referendum. However, that following spring UNI would face one of the largest events to happen on the campus during its history, the UNI 7. Throughout 1969 and 1970, the Afro-American Society, led by UNI students Palmer Byrd and Sam Dell, had been working with the administration at UNI to establish a minority culture house on campus. The process, however, was arduous and the prospect of minority students having their own cultural house drew flak from administrators and parents of students alike. So, in March 1970, 10 African-American students at UNI visited President Maucker’s home late at night to have a discussion with him to take more concrete action on the request for a minority culture house before the board of regents. However, the discussion became visibly heated as the hours went on and President Maucker repeated that he would not sign a document for a specific house and demanded that they leave. The students refused and Maucker returned with his wife to bed while a night guard sat with the youth in the living room as they decided to sit still until some action was taken. By the next morning, rumors began to fly around campus and students began to clamor around the President’s House to view the commotion. By then the sit-in had grown to 40 individuals as radical elements and sympathetic liberals showed their support to the Afro-American students against the slowness of “the system”[19] But after a few more hours, the arrival of the press, and an incoming injunction, the sit-in students elected to move to an administrative building to continue their sit-in, but decided to end the sit-in with no press release which might rile up the administration and media. By the end of the week, Dean Eddie Voldseth announced that seven students were to be suspended pending an investigation by the student conduct board. By the March 31, 1970 issue, the Primer had begun to cover the case and the subsequent student hearings. The staff also worked with other students to storm the hearings and helped solidify a growing campus movement that fed off the growing student dissatisfaction of the administration with the 7.[20] Then with the coming of the invasion of Cambodia and the Kent State killings, the campus grew more divided as there were those who wanted to act and those who did not. But by then another summer was on the way and most students at UNI had packed up to go home. That summer was predicted to be the summer of “Ohio”, or the summer in which the radicals and progressives alike take extreme action in honor of the dead at Kent State. However, this prediction never came to pass. Once students returned to UNI in in the fall of 1970, the political fervor and calls for radical change had seemingly disappeared overnight. While the Primer did return that fall, almost all the papers veterans and staff had either graduated or lost interest. The paper was then edited collectively by John O’Connor, Dick Faust, Bill Yates, and Diana Morgan with a shifting focus away from the “freak” audience that had been its base. John O’Connor thought that while the counterculture and drugs had been useful in radicalizing people, it was coming to the point where it was becoming counterproductive. O’Connor instead sought to change the Primer from being an entertaining, informative magazine for the counterculture to being like that of a classical, educational journal that sought to discuss theory and ideology. In O’Connor’s own words, “We’d like to think people would rather read about a problem and make up their own minds than go to a Speak-Out and find out what happens to be in the wind that day. It is unfortunate that people around here seem to think they need a leader for solutions. They should come to their own conclusions. But this is not to say that they shouldn’t unite, once those conclusions have been reached. We hope that the articles we’re printing now will help people to become better informed, so that the eventual decisions reached will be the right ones.”[21] In this stripped down format the Primer hoped that by losing the “freak” edge they would be better able to reach liberals and workers alike. But this third edition of the New Prairie Primer lasted for only 8 issues from June of 1970 to December of 1970. The Primer finally floundered in December 1970 after a lack of money prevented them from printing any more issues. Considered the longest running underground paper in the history of the state of Iowa, the New Prairie Primer had only lasted for two-and-a-half years. As such, the New Prairie Primer was the first and last of its kind on the campus of the University of Northern Iowa. While this wouldn’t spell the end of student action on campus, far from it, the end of the Primer marked the end of a short but explosive era of student politicization at the University of Northern Iowa. Dozens of committed students and volunteers spent countless hours working to create the Primer in their dorms and in the streets. But one thing is clear, we will never again see anything like the underground press of the Sixties. The technology that spawned the underground press is practically obsolete and it is simply no longer exciting or cost-efficient to transfer inked images to paper. And as John McMilian says in his book “Smoking Typewriters”, “...The movement that fueled the growth of underground newspapers is likewise extinct. Of course, the Sixties remain а force in American popular culture; so momentous were that decade's events that even subsequent generations have come of age in its afterglow. But the underground press had а specific raison d'erre: it was created to bring tidings of the youth rebellion to cities and campuses across America and to help build а mass movement. And for all its shortcomings -- intellectual, and even sometimes moral-- this is something it did remarkably well.”[22] Whether they advanced the hard-nosed analysis of SDS and its offshoots, or the likes of Huey Newton and Noam Chomsky, or championed the new liberated lifestyles seen with the Woodstock Summer, radical newspapers became the medium through which the youth transmitted their arguments and ideas to try and popularize their rebellions. And because of the underground newspapers’ extraordinary inclusiveness, they helped frame the decentralized operations and diverse social relation within the New Left. But as we saw with the Primer, this did not come easily. For many papers like the Primer, their staff were often deluged with bills they couldn’t pay, lack of time, and coordinating a group made producing an underground paper a nightmare. But this didn’t discourage thousands of youth radicals to create their own papers across the United States. After reading something like the Primer, one can see it was a finished product of love-labor that tried to communicate with kindred minds and maybe had converted a few minds along the way. The Primer’s demise is but a small example of this short, yet manic era in American history. As the Sixties ended and gave rise to the Seventies, the passionate campaigns of American radicals and their youth following had seemed to fall on deaf ears. Vietnam still lumbered on in the background for five years, Nixon and Kissinger performed their own dirty backroom deals, the enthusiasm on the campuses seemed to wane. Thus, we had entered the era of Taxi Driver and Deep Throat, the forces of evil had seemingly won as the far-right gathered momentum and prepared for the launch of Reagan and Bush less than a decade later. But the democratic sensibilities that Sixties youth had brought to journalism not only persist, but have also taken on a life of their own. And they are still likely to endure in some fashion or another. For radicals today, the internet holds tremendous promise and opportunity with the rise of online forums, social media, and internet podcasts. But much of what the 2000s blogosphere and left-wing YouTube, referred to as “BreadTube,” have accomplished today with building communities and democratizing the media was accomplished more than 40 years ago by the frank, vulgar, and threadbare papers of the underground press. While there may be little evidence left of the Primer’s impact on the University of Northern Iowa, the culture of student activism hasn’t completely died out. While it lies mostly nascent, the vigor and passion of the 1960s still emerges for a moment every decade or so. Whether that be the Iraq War protests of the 2000s or the Racial and Ethnic Coalition of 2019, and statewide campaigns by Iowa Student Action. In conclusion, the story of UNI’s underground press and its student staff stands as an example of the burgeoning political and social changes seen in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. At UNI, small-town Iowa students and working-class youth became the messengers of radical politics and student action during their time. The culture the Primer spread to the masses persists today with the new generation of radicalized youth. Notes [1] McMillian, James. Smoking Typewriters (New York; Oxford University Press, 2011), 4. [2] Hoffman, Abbie. Steal This Book (Pirate Editions, Grove Press, 1971), 92. [3] Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 1.” Northern Iowan, February 12, 1971. [4] Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 1.” Northern Iowan, February 12, 1971 [5] Niceswanger, Bruno. “Editor’s Note.” New Prairie Primer, December 9, 1968. [6] Niceswanger, Bruno. “Editor’s Note.” New Prairie Primer, January 27, 1969. [7] Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 1.” Northern Iowan, February 12, 1971 [8] Quegg, David. “In This Issue.” New Prairie Primer, October 4, 1969. [9] Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 1.” Northern Iowan, February 12, 1971 [10] “Scenes from the Revolution: Iowa #1.” New Prairie Primer, October 25, 1969. [11] Wherry, Peg. “Underground Newspaper In Circulation Under New Name.” Northern Iowan, October 7, 1969. [12] Severin, Bill. “Bill Severin, the Iron Duke.” Waterloo Daily Courier, October 12, 1969. [13] Bruno Niceswanger, et all. “Duke Blasts Bedfellows!!!” New Prairie Primer, October 25, 1969. [14] “Primer Special Drug Supplement.” New Prairie Primer, March 3, 1970. [15] Bruno Niceswanger, et all. “3 Viet Vets Rap on the War.” New Prairie Primer, November 13, 1969. [16] Nelson, Thomas. “This week marks 50 years since the 1968 riot in Waterloo. We look back.” The Courier, September 9, 2018. [17] “.” New Prairie Primer, April 27, 1970. [18] “Revolutionary Student Government Declared.” New Prairie Primer, March 31, 1970. [19] Ogden, Tony. “UNI 7.” New Prairie Primer, March 31, 1970. [20] Niceswanger, Bruno. “The UNI Struggle: What It Means.” New Prairie Primer, April 27, 1970. [21] Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 3.” Northern Iowan, February 19, 1971 [22] McMillian, James. Smoking Typewriters (New York; Oxford University Press, 2011), 188. Bibliography Hoffman, Abbie. Steal This Book (Pirate Editions, Grove Press, 1971) McMillian, James. Smoking Typewriters (New York; Oxford University Press, 2011) Nelson, Thomas. “This Week Marks 50 Years since the 1968 Riot in Waterloo. We Look Back.” The Courier. September 9, 2018. https://wcfcourier.com/news/local/this-week-marks-years-since-the-riot-in-waterloo-we/article_761a2ea4-3bdb-5ea9-89f7-e90172d41a82.html. Niceswanger, Bruno, et all. “3 Viet Vets Rap on the War.” New Prairie Primer, November 13, 1969. Niceswanger, Bruno, et all. “Duke Blasts Bedfellows!!!” New Prairie Primer, October 25, 1969. Niceswanger, Bruno. “Editor’s Note.” New Prairie Primer, December 9, 1968. Niceswanger, Bruno. “Editor’s Note.” New Prairie Primer, January 27, 1969. Niceswanger, Bruno. “The UNI Struggle: What It Means.” New Prairie Primer, April 27, 1970. Ogden, Tony. “UNI 7.” New Prairie Primer, March 31, 1970. Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 1.” Northern Iowan, February 12, 1971. Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 2.” Northern Iowan, February 15, 1971. Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 3.” Northern Iowan, February 19, 1971. Quegg, David. “In This Issue.” New Prairie Primer, October 4, 1969. Severin, Bill. “Bill Severin, the Iron Duke.” Waterloo Daily Courier, October 12, 1969. Shackelford, Christopher J., "A Midwestern culture of civility: Student activism at the University of Northern Iowa during the Maucker years (1967-1970)" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 29 Wherry, Peg. “Underground Newspaper In Circulation Under New Name.” Northern Iowan, October 7, 1969. “Primer Special Drug Supplement.” New Prairie Primer, March 3, 1970. “Revolutionary Student Government Declared.” New Prairie Primer, March 31, 1970. “Scenes from the Revolution: Iowa #1.” New Prairie Primer, October 25, 1969. “Special Edition on Life” New Prairie Primer, April 27, 1970. AuthorTy Kral is an undergraduate student of History at the University of Northern Iowa, with a primary focus on public history and museum studies. Ty is a socialist obsessed with the study of history and is particularly interested in Marxist thought, Iowa history, and the history of the Soviet Union. He has been a member of the UNI YDSA for over two years. After school, Ty hopes to find work in museums or archives and eventually go to graduate school.

0 Comments

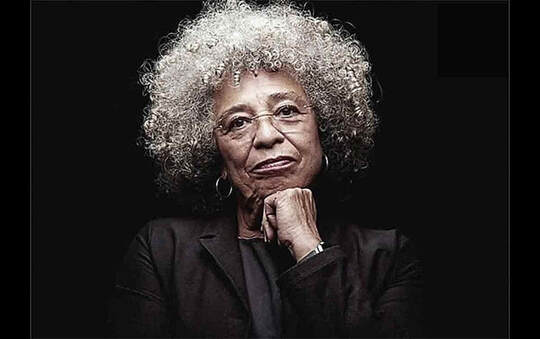

The cries to be intersectional echo from every corner of the woke left. Those who are deemed to be not “intersectional” are shamed as TERFs, class reductionists, brocialists, or even fascists and right-wingers. Of course as leftists we should condemn bigotry wherever it may occur, even within our own movements and organizations. But that does not mean we should uncritically support all ideas that arise within the left. Especially something like intersectionality which arose out of the academic new left, which was propped up and funded by bourgeois elements like the CIA. Nothing must be left unchallenged or uncriticized, intersectionality included. Intersectionality is commonly defined as the intersection of multiple oppressions typically caused by identities such as race, class, sex, gender, etc, resulting in the creation of overlapping and interdependent forms of oppression. Intersectionalists call that no form of oppression be thought of and treated separately. An example of this is with abortion laws, how they don’t exclusively affect women negatively, but disproportionately harm women of color and working class communities. While there is nothing fundamentally wrong with this explanation, that’s all it is. Rarely is there a coherent solution that intersectionalists offer. Additionally, Marxists have long recognized this fact that oppressions can overlap and intersect. Engels recognized the intersection of class and gender in The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, as did Marx, Lenin, Kollontai, Hampton, etc. The only difference however, is that this pattern wasn’t called intersectionality, people weren’t called to be “intersectional” rather the word intersectional was replaced with the word solidarity. However, there are many issues amongst the supporters and theoreticians of intersectionality, the main issue being that identities such as race, sex, and gender are seen as these abstract isolated floating bodies, there is very little material analysis within intersectional analysis. Intersectionalists call for a comprehensive and inclusive approach to help the marginalized groups but what is an intersectional solution? Many of the marginalized peoples that intersectionality advocate for are in the working class. Women are more likely to live in poverty than men. According to the Center for American Progress of the 38 million people in poverty 21 million of them are women. In 2019, using data from the Census Bureau, poverty rates for Black and Hispanic people were at 18.8 percent and 15.7 percent, almost ten points greater than Non-Hispanic White people. And according to the Williams Institute 22% of LGBTQ people live in poverty compared to 16% for cisgendered people. Transgender and bisexual cis women have a povety rate at about 29%. People of marginalized identities (PMI) face significantly higher poverty rates than the national average. Poverty and class based oppression is a major issue in many marginalized communities, yet in many discussions about intersectionality rarely does class get brought up, or it is seen as a secondary subject. Additionally, in many “progressive” circles the working class, especially the rural working class is dismissed as a monolith of white people in the Midwest who hold reactionary views. This view is not only incredibly wrong, it’s classist and bigoted, as it’s marginalized people who suffer poverty at higher rates, especially if they live in rural areas. That’s not to forget of course that much of the language surrounding intersectionality and the woke left is incredibly alienating to the working class, including PMI working class. According to a Yale study people responded more favorably to policy proposals emphasizing class. The people tested were given policy proposals ,advocating for the Green New Deal, affordable housing, weed decriminalization, increasing the minimum wage, and forgiving $50,000 of student debt, framed in class, race, and race + class lens. The policy proposals framed with class did the best. What this shows is that even if you care about racial justice the best way to help minorities is to frame your policies in a way that emphasizes class. People care about bread and butter issues, and we don’t need a Yale study to back this up, we can look at the Sanders campaign. The Sanders campaign for a long time polled incredibly well among minorities. In California, he had an approval rate of 49 percent among Latinos, and 39 percent in Texas. Sanders also did incredibly well among young black people and LGBT (4 in 10 LGBT voters supported Sanders). Sanders championed a platform of class based issues, most notably Medicare for All and Free College, issues that are explicitly class centered but benefit minorities greatly. The elites did everything they could to sabotage his campaign and threw all of their known insults towards him and his supporters, including that of “class reductionist”, “brocialist”, and “bernie bro”, never mind that Sanders had overwhelming support among women and minorities. Of course Sanders is a social democrat and many of his proposals would have been unlikely to pass due to the political system being created to serve the interests of capitalists. However, the fact that minorities and women overwhelmingly supported Sanders who is straight, white, and male over other candidates like Harris, Buttigieg, and Warren shows us that people care more about actual policy that actually helps them over symbolic gestures of wokeness. Speaking of which race/identity neutral class based policies championed by Marxists and other socialists but often sneered at or dismissed by the wokeists have helped minorities and women the most. Take social security for example which was heavily championed by Marxists and labor activists, women are the majority beneficiaries of social security, making up 56% of beneficiaries 65 and older, and 66% of beneficiaries 85 and older according to the National Academy of Social Insurance. Social security is a lifeline for many women in older age against poverty. Wokeists constantly shrill about being intersectional, and to account for all forms of oppression in one’s activism, yet they themselves rarely take into account class and how closely tied it is to the oppression of the minorities they so claim to stand with. Class is often the last issue to be brought up in woke and intersectional circles, whereas individual identities such as sex, race, and gender are raised onto a pedastal. They are seen as essential to one’s identity, regardless of one’s class position or their role to the means of production, a person becomes an amalgamation of their identities. What is more essentialist and individualistic than that? As Eve Mitchel, a marxist feminist, writes in critiquing bell hooks, “Similarly, theories of an ‘interlocking matrix of oppressions,’ simply create a list of naturalized identities, abstracted from their material and historical context. This methodology is just as ahistorical and antisocial as Betty Friedan’s” Wokeists often fail to take into account the historical and material context of identity. They claim that racism and sexism existed before capitalism therefore, so called “class reductionism” is bad (even though most accusations of class reductionism are brought up when someone starts talking about class). Yes racism and sexism existed before capitalism, but capitalism compounded the oppressions and created new ones. Additionally, capitalists have used racism and bigotry to distract from solidarity amongst the working and colonized peoples. For example, in Rwanda the Belgians favored the Tutsi minority over the Hutu majority, allowing the Tutsis to oppress the Hutus leading to resentment among the Hutus, eventually leading to the Rwandan genocide. This can also be seen even in America where the media stokes up racial fear and hatred of Black, Asian, Latino, and Middles Eastern people to prevent the white working class from recognizing that it’s not immigrants or people of color who are stealing their jobs, but rather it’s the capitalists who are exploiting them and making them replaceable. The isms and phobias don’t exist in a vacuum; they are enforced by class society. It has always been the upper classes who have stoked racial and xenophobic tensions. It wasn’t the people of Rome who decided randomly to go fight the Goths but the patricians who commanded the people of Rome to fight against the Germanic tribes to protect and expand the borders of Rome. The same can be said today in America and in the imperial cores. It is the upper classes, the bourgeoisie who stoke racial tensions through the media, education, popular and high culture and combined with a loss of jobs and lack of prospects create resentment amongst the white working class. The saying “It’s a rich man’s war but a poor man’s fight” describing the draft on both ends that was supposed to be applied to all men of combat age but ended up being dodged by the wealthy can be applied today. The military is largely composed of underprivileged people of various ethnic origins, it’s poor schools that recruiters target not the wealthy ones, yet the wokeists rarely acknowledge that, heck they don’t even seem to acknowledge imperialism or even question the imperialist narrative at all! If anything they’d rather make it “intersectional” as seen with the recent military and CIA ads featuring women and people of color. This is nothing new as imperialists have historically used progressive cases to further imperialism and even more insidiously they have been absorbed without question by the social democrats and many so called “intersectional” leftists who believe the imperialist narrative about many anti-imperialist countries such as Syria, Venezuela, Iran, Russia, China, the former USSR, etc. The intersectionalists fail to recognize that class society is at the root of racism and sexism, or that people of color, women, and lgbtq people make up a large portion of the working class. If they truly want to eradicate racism and sexism they would focus their attention on the bourgeoisie, the bankers, financiers, and landlords who contribute nothing while leeching off of the hard work of workers (often of marginalized identities themselves) rather than sowing division and preventing solidarity! History is a class struggle not an identity struggle. It is through class struggle that has paved the way for social progress and our conceptions and ideas of identity are based in the mode of production. However, intersectionalists fail to recognize that, rather they see identity and bigotry as abstract floating bodies in space. They see oppression as signs of individual hate rather than a way for capitalists to more ruthlessly exploit one section of the population, driving the working conditions down for all workers and preventing solidarity. Intersectionality has failed to recognize this, rather the ideology’s followers fail to recognize how entrenched class society, particularly capitalism, in every facet of our lives. They see identities as lines that are intersecting with each other forming unique and individual experiences of oppression, yet they fail to see the class nature behind the oppression, and often any critique of their philosophy is often dismissed as reductionist or right wing. However, no mode of thought is immune to criticism, especially one that makes claims as outlandish as intersectionality. Links https://libcom.org/library/i-am-woman-human-marxist-feminist-critique-intersectionality-theory-eve-mitchell https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.14361/9783839441602-006/pdf https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0vnLzfRqPS8&ab_channel=sev_k https://www.lfks.net/en/content/fred-hampton-its-class-struggle-goddammit-november-1969 https://www.marxist.com/marxism-vs-intersectionality.htm https://claudepeppercenter.fsu.edu/the-myth-of-class-reductionism/ https://newrepublic.com/article/154996/myth-class-reductionism?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=tnr_daily https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7gEHVZQLPLk&ab_channel=PeterCoffin https://www.historicalmaterialism.org/articles/intersectionality-and-marxism https://osf.io/tdkf3/ https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2020/08/03/488536/basic-facts-women-poverty/ https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2020/09/poverty-rates-for-blacks-and-hispanics-reached-historic-lows-in-2019.html https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/lgbt-poverty-us/ https://www.vox.com/2020/3/4/21164235/latino-vote-texas-california-bernie-sanders-super-tuesday https://thehill.com/homenews/campaign/485877-nbc-exit-poll-shows-sanders-with-most-support-from-lgbtq-voters?rl=1 https://www.nasi.org/education/womens-stake-in-social-security/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GnUqrF9mAA8&t=1642s https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ovIW4JG2nVI&ab_channel=SecularTalk AuthorN.C. Cai is a Chinese American Marxist Feminist. She is interested in socialist feminism, Western imperialism, history, and domestic policy, specifically in regards to drug laws, reproductive justice, and healthcare. Within the last few decades, we have seen the emergence of neoliberal feminism, feminism that is seemingly revolutionary yet maintains the institution of capitalism. Though completely contradictory to each other, for most, feminism and capitalism come hand in hand. Feminism is to many, “the advocacy for equality between the sexes,” and in a lot of ways that translate to diversifying the workplace and politics. But this is antithetical to any sort of real change, extending power to a few oppressed people will not liberate a majority of the oppressed. Covertly, this form of feminism has been more effective in harming the communities it claims to protect than actually protecting them. It has given us the illusion of progress when in reality it hasn’t even achieved the bare minimum for social change. In fact, it has been overwhelmingly successful in forcing the complacency of oppressed people; because finding a solution to their suffering was never the goal. To a certain point, it has convinced us that a woman in power is the solution to patriarchal oppression. Amongst the empowerment narratives pushed by neoliberal feminists we have only seen the continued normalization of the exploitation and oppression of proletarian women, especially trans women and women of color. The normalization and even encouragement towards the sex trade is one example that comes to mind. Participation in the sex trade is in almost every circumstance the result of economic desperation and when someone has to rely on the trade for their primary source of income, which tends to be the case for most involved, the ability to consent is removed from the situation. Trans women and women of color have been disproportionally affected by the sex trade with 40% of black women and 24% of Latinx women having been reported as victims of sex trafficking (Banks and Kyckelhahn). Meanwhile, roughly 10.8% of transgender people have reported participating in the sex trade with transwomen being twice as likely to participate than transmen (Fitzgerald). Neoliberal feminism has conditioned us to ignore the material conditions that requires individuals to become involved in the sex trade in the first place. It has become so ingrained in our collective psyche to the point of idolization of the trade. That is the genius behind neoliberal feminism. It creates empowerment in being the exploiter and in being the exploited. Such as the recent phenomenon of things like “OnlyFans.com” and the massive support from neoliberal and liberal feminists alike. While it has made it possible for participation in the sex trade to be safer for those involved (which is objectively a good thing), it is still extremely exploitive and predatory. Simply put, creating a better alternative to a bad and exploitive thing does not make it no longer bad or exploitive. Whether advertently or inadvertently, support of these industries by neoliberal and liberal feminists is less successful in demystifying the stigma towards individuals in the sex trade and more so successful in promotioting the commodification of individuals bodies. As well as promoting the capital interests of these industries. But this is not at all to say that participating in the sex trade is shameful, entirely nonconsensual, or entirely unempowering to every individual. Although, we have seen from the perception of the sex trade through the neoliberal gaze not only a lack of comprehensive understanding of these industries but a lack of intersectional understanding of feminism as a whole. Having an intersectional approach to feminism is vital as feminism without intersectionality can quickly become a tool for enforcing white power. Like I said earlier, feminism is widely recognized as “the advocacy for equality between the sexes.” What this misses however is how women can be discriminated against for various identities beyond gender. Without acknowledging this and acting according to this fact, your advocacy is not for all women but for one type of woman. This type of woman oftentimes being cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied, upper-class, and white. When the bulk of feminist advocacy is not intersectional, it results in upholding and enforcing white power structures rather than aiding in ending the oppression faced by all women. Through the advocacy of “white feminism” as it is commonly referred to and neoliberal feminism, the oppression of proletarian women persists. In a lot of ways, neoliberal feminism and white feminism go hand in hand to perpetuate oppression. But how can intersectional feminism work to alleviate and even eradicate these forms of oppression? By viewing feminism through an intersectional lens and understanding how someone may be discriminated against because of various identities, we can begin to understand that feminism is not and can not be just one thing. There is no one solution to the inequalities women face, but by pushing forward the voices that experience these overlapping modes of discrimination, recognizing the historical context associated with these issues, recognizing how these marginalized groups are at the highest risk for experiencing natural disasters, health issues, poverty, gender-based violence, etc, and looking at how our system reproduces these inequalities can help us approach these issues in a way that can actually create positive change. The work of Angela Y. Davis is a great example of exploring intersectional feminism; her historical and dialectical approach to exploring feminism is effective in helping us understand how it is deeply rooted in white supremacy. Her analysis of the women’s suffrage movement can really be applied here. “Whether the criticism of the Fourteenth and Fifthteenth Amendments expressed by the leaders of the women’s rights movement was justifiable or not is still being debated. But one thing seems clear: their defense of their own interests as white middle-class women--in a frequently egotistical and elisist fashion--exposed the tenuous and superficial nature of their relationship to the postwar campaign for Black equality” (Davis). Their position was not to push for equality of all oppressed people or all oppressed women, in fact. Rather their position was one heavily rooted in white supremacy and held bourgeois interests, choosing to mostly separate themselves from issues that were not those of the white middle-class woman. To this day many white feminists have not far separated themselves from that position. Neoliberal Feminism and white feminism have created a barrier for progression and embracing intersectional feminism can help demystify many of the inequalities perpetuated in our current systems. Understanding intersectionality and deconstructing much of the racist ideology of these forms of feminism is crucial to truly transform our society for the better. Without looking at feminism through an intersectional lens, being critical of these forms of feminism, and being anti-capitalist in your approach, then feminism will continue to truly be antithetical to real progress. Work Cited Banks , Duren. “Characteristics of Suspected Human Trafficking Incidents, 2008-2010.” Bureau of Justice Statistics, Apr. 2011, www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cshti0810.pdf. Women, Race and Class, by Angela Y. Davis, Vintage Books , 1983, pp. 76–76. Fitzgerald, Erin. Meaningful Work: Transgender Experiences in the Sex Trade. National Center for Transgender Equality, Dec. 2015, Meaningful Work-Full Report_FINAL_3.pdf AuthorTara Thomason is pursuing an bachelor’s in Political Science and Gender Studies. Their main interests are police and prison abolition, decolonization, black liberation, women liberation, and the global proletarian struggle. Much of their work goes towards organizing mutual aid efforts in my community and educating on Marxism. Over the course of Mexican history, culture and heritage have been used in multiple ways by the state. During the Porfiriato, the state tried to centralize heritage to fan the flames of nationalism within Mexican borders. As a result, multiple heritage sites and artifacts were taken over by the state and taken away from the rightful indigenous owners of these places and items. During the 20th century, the installment of more democratic institutions and (the spread of neo-liberalism into the fields of culture and heritage) was intended to benefit historically oppressed groups like the indigenous population of southern Mexico. From these massive institutional changes, global institutions like the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and state ran heritage agents like the Mexican National Institute of History and Anthropology (INAH) used tourism and other arms of capitalism to justify the exploitation of these sites. In contemporary Chiapas, Mexico we are seeing the complete subversion of this common form of the neoliberal heritage and cultural preservation model. With the presence of the Ejercito Zapatista de Liberacion Nacional (EZLN) occupying various autonomous zones in the region, the preservation of culture is done through the preservation of these communities’ ability to be autonomous and control over their land. Some would attribute this sense of culture preservation to these communities shared indigenousness, however as this paper explores, this model of heritage creation and preservation is tied to a shared class struggle, which has resulted in the use of indigenous institutions for things like governance within these autonomous zones. On January 1st, 1994 the Mexican state of Chiapas witnessed a military insurrection from the EZLN, a left-wing indigenous organization that views the Mexican state and its president as illegitimate. The EZLN embraces indigenous and Maya culture as a guiding light for how they build society within their autonomous zones, with the organization having a decentralized structure representing people from many different Maya communities like the Tzeltal, Chol, Tzozil, and Zoque among many other groups.[1] However, the roots of this movement within Chiapas are seen in the constant indigenous uprisings in the region for the last four hundred years, marked by thirteen different ethnic groups that now make up the landless peasant families and day-laborers in contemporary Chiapas.[2] These socio-economic problems are relevant in many other states in Mexico however these problems were exacerbated by the lack of land reform in the state after the revolution from 1910-1917. While the majority of Mexicans saw a revolution marked by Zapatism, Chiapas saw an internal civil war between two different groups of elites that eventually prevailed over the peasant class agraristas which resulted in a lack of land reform leaving many families landless and powerless.[3] This lack of land and autonomy had massive effects on the mindset of the indigenous people of Chiapas. One reason that may immediately come to mind is Karl Marx’s Theory of Alienation. Although the worker or peasant is an autonomous, self-realized being, because their goals, activities, and duties are dictated by the bourgeoisie due to economic centralization they lose their ability to determine life and destiny.[4] Due to outside forces, like the elite cattle farmers and planters, owning the majority of arable land, these indigenous workers have had their freedom and autonomy taken away as they now rely on the landowners to provide for them their food and wages. On top of this, to the indigenous population a lot of culture and heritage is tied to the land itself. This lack of land reform disenfranchised a majority of the population, making Chiapas a fertile area for uprisings and unrest throughout the 20th century. Even policy reforms made to benefit the laborers like the creation of Confederacion Nacional Campesina, which was meant to represent small-scale farmers and ejidatarios, failed since land reform was absent in Chiapas.[5] This organization, along with every other political and state institution, fell back on the pre-revolutionary alliances between the local elites, like the cattle farmers. [6] As more reform and neo-liberal policies were enacted over the course of the 20th century, the EZLN embraces class struggle and their tie to the land to subvert the national government’s attempts to centralize power. This eventually led to the beginning of the Chiapas conflict in 1994 when the North American Free Trade Agreement was set to begin, a treaty that the EZLN claims as a death sentence for the indigenous ethnicities of Mexico.[7] This is because NAFTA would require Mexican agriculture laws to align with that of the United States and Canada which would allow for privatization and big transnational companies to dominate the agricultural sector.[8] As seen throughout Mexican history, indigenous culture and heritage has been used as a rallying point to supplement and support the status quo as the people of Mexico should rally around their inherent “Mexicaness.” Leaders of the EZLN subvert this centralization of culture by embracing class struggle, thus creating a rallying point for these indigenous groups to gather around by embracing their disenfranchisement from their land that would result from policies like NAFTA. This disenfranchisement materialized itself in a peasant, agrarian resistance movement that prides itself on taking back land and stopping the commercialization of indigenous culture. The EZLN after rising to prominence in the 1990’s did a lot of groundwork for the future success of the indigenous people in Mexico. This became clearly apparent in 2001 when the Mexican Congress, under EZLN pressure, passed a law that recognized the rights of indigenous people giving them the ability to practice autonomy within the united nation of Mexico.[9] As a result of this, multiple EZLN autonomous zones were created all over the Chiapas region. These indigenous administrative territories use a traditional way of governance, like the Calpulli (Large House) system. The calpulli is the organizational level below altepetl or city-state. At the smallest level of this organizational structure are families, who are responsible for each other’s education and food preparation. Followed by the calpulli, which is a functional community ran by the calpiulec, the main administrator of the region who designates responsibilities and duties like what crops to grow between the families.[10] This right to self-determination resulted in indigenous people being able to maintain their traditions because they did not have to change their lifestyles. The embracing of heritage is abstract in concept and can materialize in many ways such as the preservation of sites, the use of the supernatural, or the complete erasure of sites. With the EZLN we see these indigenous communities preserving culture through their use of their own governance system, living an indigenous lifestyle free of change due to things like NAFTA . This is a stark contrast to the conservation and preservation of culture through neo-liberal means. Neo-liberal celebration of culture and heritage is not for practical purposes but rather to supplement the end means of profit. As a result, this involves the inclusion of material items and places like heritage sites as seen at Palenque, Tonina, and Chichen Itza. Here we see the exploitation of indigenous sites- that indigenous communities would like to use- to help turn a profit for the private investors who are funding these projects to centralize cultural power within the Mexican state. Despite the existence and the ability to create these autonomous zones for indigenous communities, indigenous communities are still being taken advantage of by the Mexican state and neo-Liberal agents. For example, the continued existence of heritage sites like Chichen Itza and Tonina that are used to generate wealth for non-indigenous communities and are used for non-indigenous heritage events like an Elton John concert. To combat this the EZLN has implemented multiple strategies to disrupt and stop the exploitation of indigenous culture. One common occurrence of civil disobedience are the roadblock demonstrations leading to sites like Tonina, sometimes taking donations to allow cars to pass.[11] Another tactic used by the EZLN is to just create villages in unused land to expand influence. This has actually been a problem for the state in the Lacandona Jungle and the group of sixty-six families of Lacandon elites that were awarded 614, 321 hectacres of the land displacing the twenty-six indigenous communities of various other ethnic backgrounds in the 1970’s and 1980’s.[12] To combat this, the EZLN has helped re-establish and protect these villages of subsistence farmers in the unused land. The establishment of EZLN villages in the Lacandona Jungle is a part of a grander strategy to spread the influence and power of neo-zapatism to other parts of Mexico. The EZLN does this by making being a Zapatista easy to identify with, not to mention embracing anyone willing to help their movement. To quote EZLN leader Comandante Zebedeo “If they are suffering exploitation, if they are suffering intimidation, if they are not receiving a just salary, then they can be considered Zapatistas, because that is our struggle as well. This is what we want, I think many people sympathize with us, because in reality that is perhaps what the great majority of our country and the world are suffering.”[13] This brings up the important point of EZLN culture and heritage building that is vastly different from most western ideas of the two. The EZLN, while it uses indigenous culture, is at the forefront of fighting for indigenous rights, and is made up of mostly indigenous groups like Tzetal and Chol, derives its cultural power from a class view of society. This use of the dynamic between the oppressed and the oppressor has been seen throughout this paper, as many of the EZLN’s tactics are used to disrupt the norms of neo-liberal imperialism and oppression through land and wealth concentration. This is a struggle that is very apparent in Southern Mexico’s indigenous communities hence the embrace of indigenous institutions like the calpulli system. This is not to say that the EZLN is the end all and be all for the indigenous community of Mexico. While the indigenous people of Chiapas may have found freedom in autonomy and defiance of the Mexican state, one should not ignore the massive material downsides. Chiapas provides more than half of Mexico’s hydroelectricity and thirty percent of Mexico’s total water, yet around ninety percent of the indigenous population in Chiapas do not have energy or plumbing. On top of this these indigenous communities lack proper healthcare, with less than one doctor per thousand inhabitants.[14] While these may speak to the lack of material improvement for these communities, an argument can be made that the material state of these communities would be the same if not worse under the neo-liberal system that involves wage slavery and reliance on systems and people that are unaccountable. Another criticism levied at the EZLN is their inability to unite all indigenous communities, as seen with the tensions between the EZLN backed indigenous villages and the Lacandon indigenous population over the use of the Lacandona Jungle. However, this criticism misses the point of the EZLN and how they have developed their culture. The essence of EZLN does not rely on the indigeneity of the people, rather their position within the standing power structure. The Lacandon people do not fit in when observed through this lens as they view themselves through a sense of culture and reject the view of class struggle. This is due, in some part, to the Mexican Government’s attempts to preserve the Lacandon culture in the 70’s and 80’s which resulted in the disenfranchisement of the many indigenous communities that now make up the EZLN. In essence, the story of building, conserving, and preserving culture and heritage within the EZLN framework is to fill the negative spaces of neo-liberalism. Zapatistas diverge immediately from the neo-liberal model through how they preserve culture. The preservation of culture is done through the preservation of these community’s ability to be autonomous and have control over their land. This can be seen in the EZLN’s establishment of indigenous political organizational structures like the calpulli and their efforts to retake land that indigenous communities were removed from in the Lacandona Jungle. This foils the neo-liberal model of obtaining physical items or preserving places and, in essence, taking away all practicality. To put culture on display as the exotic other within the country it is supposed to represent. Another major diversion in the EZLN’s perception of culture and heritage is how they create an identity. While the EZLN is heavily associated with and often called an indigenous movement, identity within the group is not centered around ethnicity. While many may disagree due to the EZLN’s prominence in fighting for things like indigenous rights in Mexico, this evidence is purely circumstantial due to where and when the movement was created. At its core to be a Zapatista, you have to side with the oppressed, the exploited, and form solidarity to conquer their struggle. This focus on class is why the EZLN is able to rally people from multiple indigenous groups in the most ethnically diverse state of Mexico. The basis of indigenous association with the EZLN is found in this class struggle as indigenous groups have been historically oppressed. All in all, this opposition to the neo-liberal status quo, through autonomy, self-subsistence, and class solidarity is how the EZLN preserves heritage in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas. Bibliography [1] Godelmann, Iker Reyes. “The Zapatista Movement: The Fight for Indigenous Rights in Mexico.” [2] Dietz, Gunther. “Neozapatismo and Ethnic Movements in Chiapas, Mexico: Background Information on the Armed Uprising of the EZLN.” Pp 27 [3] Dietz, Gunther. “Neozapatismo and Ethnic Movements in Chiapas, Mexico: Background Information on the Armed Uprising of the EZLN.” Pp 27 [4] MARX, KARL. Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 [5] Dietz, Gunther. “Neozapatismo and Ethnic Movements in Chiapas, Mexico: Background Information on the Armed Uprising of the EZLN.” Pp 27 [6] Dietz, Gunther. “Neozapatismo and Ethnic Movements in Chiapas, Mexico: Background Information on the Armed Uprising of the EZLN.” Pp 27 [7] Shantz, Jeff. “Understanding the Chiapas Rebellion: Modernist Visions and the Invisible Indian.” [8] Godelmann, Iker Reyes. “The Zapatista Movement: The Fight for Indigenous Rights in Mexico.” [9] Godelmann, Iker Reyes. “The Zapatista Movement: The Fight for Indigenous Rights in Mexico.” [10] Godelmann, Iker Reyes. “The Zapatista Movement: The Fight for Indigenous Rights in Mexico.” [11] Schafer, Norma “Tonina, Hidden Chiapas Archeology Gem: The Road Less Traveled.” [12] Vegara-Camus, Leandro. “The MST and the EZLN Struggle for Land: New Forms of Peasant Rebellions.” [13] Callahan, Manuel. “Why Not Share a Dream? Zapatismo As Political and Cultural Practice.” [14] Godelmann, Iker Reyes. “The Zapatista Movement: The Fight for Indigenous Rights in Mexico.” AuthorDanny Ogden is an undergraduate student of Political Science and History at Florida State University, with a primary focus on Comparative Politics and Latin American History. Danny just recently started diving into Marxist thought and is super interested in the EZLN. After school Danny wants to go to Law school and eventually work for an organization like the Equal Justice Initiative or as a Public Defender. Archives |

Details

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

About the Midwestern Marx Youth LeagueThe Midwestern Marx Youth League (MMYL) was created to allow comrades in undergraduate or below to publish their work as they continue to develop both writing skills and knowledge of socialist and communist studies. Due to our unexpected popularity on Tik Tok, many young authors have approached us hoping to publish their work. We believe the most productive way to use this platform in a youth inclusive manner would be to form the youth league. This will give our young writers a platform to develop their writing and to discuss theory, history, and campus organizational affairs. The youth league will also be working with the editorial board to ensure theoretical development. If you are interested in joining the youth league please visit the submissions section for more information on how to contact us!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed