|

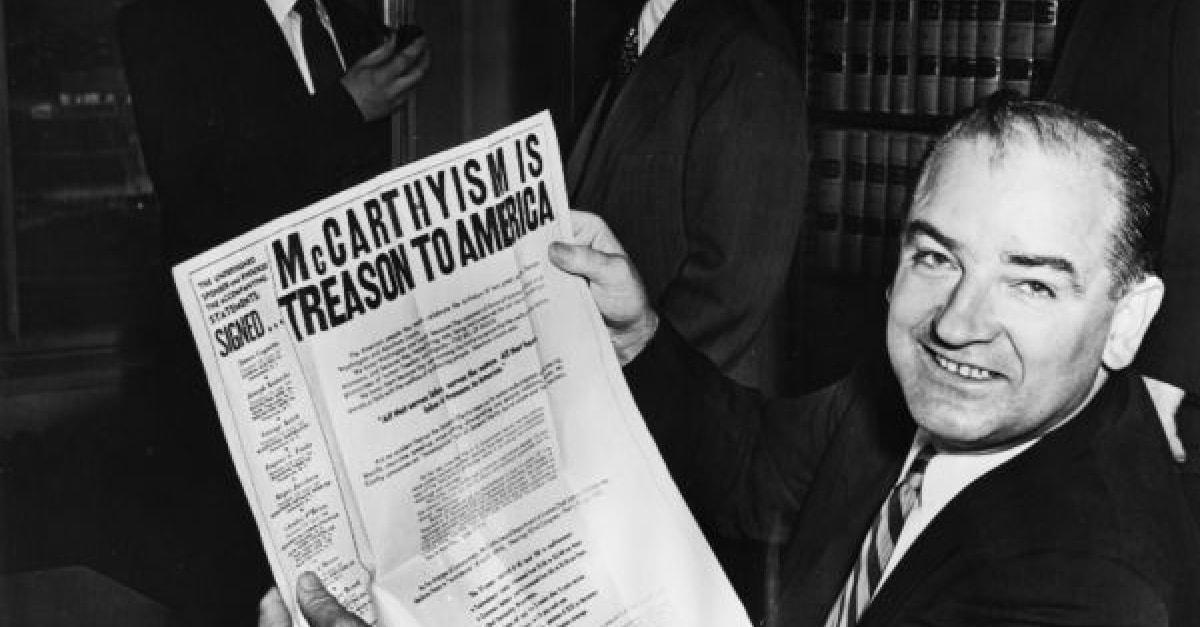

12/28/2022 McCarthyism and the Constitution:How the Second Red Scare Led to the Violation of the Constitution and its Amendments By: Nolan LongRead Now“McCarthyism,” as a term, generally refers to the illegal political persecution of communists by government officials. As such, the present essay deals with not just the figure Joseph McCarthy, but with the entirety of the anti-communist repressions led by the United States government during the period of the “Second Red Scare,” which lasted from the 1940s through the 1950s. Although there is an argument to be made that the “Red Scare,” as it were, is a policy and sociological idea that continued until 1991, the period of the 1940s-50s in particular is representative of mass governmental repression and persecution of American communists. The anti-communist impulse led to trials of communists and non-communists alike. The unconstitutional nature of congressional hearings, House committees, trials, and public persecution of communists can be seen in the cases of the Hollywood Ten, the Communist Party USA, and other parties, individuals, and organizations. The Constitution, its amendments, and other founding documents of the United States were violated in the governmental persecution of communists in this chapter of American history. The idea of McCarthyism finds its roots in the clearer practice of anti-communism. The political conditions of the postwar period shifted social focus onto the “red menace” that was the socialist world, which was growing in numbers. The American fear of communism is what led to their unconstitutional persecution of said ideology. Senator McCarthy “argued against freedom of speech because much of his rhetoric assumed that any discussion of the ideas underlying communism was dangerous and un-American” (Pufong). That is, the belief that so-called un-American activities were a threat to national security is what led the anti-communists to repress civil liberties. The most important piece of anti-communist legislation passed during this era was the Smith Act of 1940. It “criminalized speech allegedly meant to cause the overthrow of the government” (Bruce, 25). Passed before the end of the Second World War, the Smith Act was originally used for the persecution and deportation of foreign-born residents with ties to left-wing politics, presently or in the past (Schrecker, 393-394). But following the end of the War, and with American-Soviet relations on the decline, the Smith Act began to be used to persecute American communists. Himself just one component of the larger Second Red Scare, senator Joseph McCarthy made a name for himself through the persecution of communists within the US Congress. While congressional hearings intended to obtain information or conduct investigations are legal, those of McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) were conducted like trials, not hearings. “Joseph McCarthy spearheaded investigations with little evidence” (Pufong). Those who opposed the Senator’s methods called these hearings “witch hunts,” implying there was no real evidence for his claims; McCarthy used such tactics as public accusations, disregard for evidence, and “unfair investigatory methods” (Pufong). McCarthy, despite being a congressperson, was acting as though he were a judge, thus violating Article I of the US Constitution, which outlines the responsibilities and limits of the Congress. Jurisprudence is not included in the powers of Congress. Section 8 of Article I states that Congress has the power to “constitute Tribunals inferior to the Supreme Court.” But McCarthy’s trials were not constitutionally grounded, as they were not based on proper judicial procedures, as they were operating based on a law which Congress itself had passed, and because they were ignoring Article III, Section 2, whereby all judicial power is granted to the courts. The general unlawful nature of the McCarthy and HUAC proceedings excluded normal court and appeal processes. It can therefore be concluded that both McCarthy and the HUAC violated Articles I and III of the Constitution. The courts were indeed subverted during the Second Red Scare, giving unconstitutional judicial power to the US Congress. “[Historian Robert] Harris found the courts proved largely powerless when faced with a rabid executive and legislature, supported by a militant public, all determined to bend civil liberties ostensibly to provide for national security” (Bruce, 33). The McCarthyism of the Second Red Scare began to be associated with denying legal rights and due process of the law; professor of politics Marc Pufong claims that the McCarthy trials violated the Fourteenth Amendment, as the insufficient evidence and lack of due process in the trials deprived the defendants of their right to equal protection of the law. Some lawyers representing the Hollywood Ten said the HUAC trials of their clients violated the Fifth Amendment (Horne, 211). Others argued that “what HUAC did amounted to a bill of attainder, an unconstitutional targeting of one recognizable group – Communists” (199). Bills of attainder are forbidden under Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution, meaning this is yet another violation. The consequences of such anti-communist trials were incredible: they led to the defendants’ public scrutiny, professional termination, deportation, and fleeing from the United States. This certainly violates the promise of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness/property which is spoken of in both the Fourteen Amendment and the Declaration of Independence. Because McCarthy and HUAC were, in effect, acting as courts in these trials, they were subverting American democracy by raising Congress above the level of checks and balances, so that it was operating on its own in legislation, execution, and jurisprudence. Article III, Section 3 of the Constitution outlines the nature of Treason as “levying War against [the United States], or in adhering to their Enemies.” But it was the Smith Act, not this section of the Constitution that was not the basis for the persecution of hundreds of communists during the Second Red Scare. The Smith Act was, in effect, redefining treason as any “subversive” leftist activity or association. This legislation was, then, in violation of Article III, Section 3 of the Constitution. Anti-communist public officials began using this act to justify ever more outlandish accusations of crime among American communists and their organizations. In 1948, “the government argued that the Communist Party was part of a conspiracy to advance a political ideology whose eventual goal was the destruction of the U.S. government” (Thomson). This claim was made without substantial evidence. When the law was brought to the Supreme Court as unconstitutional in 1951, they ruled that the First Amendment was not violated by the Smith Act because of the Clear and Present Danger standard. Morone and Kersh define this standard as “court doctrine that permits restrictions of free speech if officials believe that the speech will lead to prohibited action such as violence or terrorism” (Morone, 124). Political scientist Claudius Johnson noted how the Clear and Present Danger standard was modified to become the “Clear and Probable Danger” standard (Bruce, 34). This change in standards came about to give the government more leeway for the repression of communists’ civil liberties, without worry of constitutional challenge. So, the very standard for the First Amendment had to be changed by the highest court in the country, just so that the prosecutions of the Second Red Scare could continue. But the Smith Act did not go unchallenged: many more communists, lawyers, and regular citizens referred to the act as a violation of the First Amendment. The HUAC violated the First Amendment in numerous ways. Not the least among them was the case of the Hollywood Ten, where the Committee blacklisted certain writers, actors, and directors from filmmaking; they persecuted leftist filmmakers for the creation of “communist” films, a clear violation of the First Amendment (Horne, 197). In cases unrelated to the Hollywood Ten, the prosecution used another tactic to attain conviction verdicts against communists: multi-defendant trials. Where leading communists were found to violate the Smith Act (which itself was later found to be unconstitutional, leading to numerous amendments to the law), innocent communists who themselves could not be convicted of conspiracy to overthrow the government were found guilty by association in multi-defendant trials (Bruce, 34). Membership in the CPUSA itself was determined a felony by multiple court decisions, an unconstitutional act which would not be overturned until 1961 (Thomson). The United States government was obviously aware that the actions carried out under the pretense of the Smith Act were unconstitutional. The FBI, a key organization in the anti-communist movement, allied with the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) for the purpose of subverting the Constitution; “the FBI apparently made use of the INS’ immunity from constitutional restraints” (Schrecker, 399). Awareness of the unconstitutionality of the anti-communist measures taken by the American government began to surface in court decisions in the late 1950s through the 1960s. In the 1951 Dennis v. United States case that upheld the convictions of eleven CPUSA leaders, Supreme Court Justice William Douglas dissented from the other Justices, saying, “any real danger presented by the communists would likely come from an alliance with the Soviet Union,” of which there was no real evidence (Bruce, 34-35). 1957 was a landmark year, as it repealed several convictions that had been won under the Smith Act by declaring its methods, wording, and prosecutions unconstitutional; the Supreme Court ruled in Yates v. United States that political rhetoric and advocacy was protected by the First Amendment (36). In 1961, criminalization of CPUSA membership was finally reversed (Thomson). The unconstitutionality of the anti-communist measures adopted by the United States government during the period of the Second Red Scare can be seen both in the methods it undertook (illegal trials, subversion of checks and balances, limitation of freedom of speech, etc.) and in the court reversals of such standards that took place in the years after. Court recognition that these methods were unconstitutional vindicates the belief that the entirety of the McCarthyite persecutions were illegal and in violation of the Constitution all along. Bibliography Bruce, Erik. “Dangerous World, Dangerous Liberties: Aspects of the Smith Act Prosecutions.” American Communist History 13, no. 1 (2014): 25-38, web-s-ebscohost-com.cyber.usask.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=fdfef7b4-e35c-4350-b7a3-50ff36bf4ee9%40redis Horne, Gerald. The Final Victim of the Blacklist: John Howard Lawson, Dean of the Hollywood Ten. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006. Morone, James A., and Rogan Kersh. By the People: Debating American Government. New York: Oxford University Press, 2021. Pufong, Marc G. “McCarthyism.” The First Amendment Encyclopedia, 2009. mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/1061/mccarthyism Schrecker, Ellen. “Immigration and Internal Security: Political Deportations During the McCarthy Era.” Science & Society 60, no. 4 (1996): 393-426. proquest.com/docview/216131205/fulltextPDF/DAC4F04720CA410APQ/1?accountid=14739 Thomson, Alec. “Smith Act of 1940.” The First Amendment Encyclopedia, 2009. mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/1048/smith-act-of-1940 United States of America Constitution, art. 1 and 3. AuthorNolan Long is a Canadian undergraduate student in political studies, with a specific interest in Marxist political theory and history. Archives October 2022

2 Comments

|

Details

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

About the Midwestern Marx Youth LeagueThe Midwestern Marx Youth League (MMYL) was created to allow comrades in undergraduate or below to publish their work as they continue to develop both writing skills and knowledge of socialist and communist studies. Due to our unexpected popularity on Tik Tok, many young authors have approached us hoping to publish their work. We believe the most productive way to use this platform in a youth inclusive manner would be to form the youth league. This will give our young writers a platform to develop their writing and to discuss theory, history, and campus organizational affairs. The youth league will also be working with the editorial board to ensure theoretical development. If you are interested in joining the youth league please visit the submissions section for more information on how to contact us!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed