|

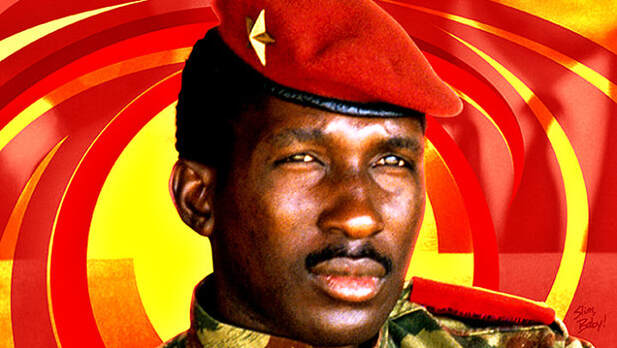

With the bombshell announcement that Burkina Faso’s longtime strongman, Blaise Compaore, will finally be tried for the murder of Thomas Sankara[1], I want to take this opportunity to bring back a particular time in history when the world could have chosen to build a new international order. In 1984, Thomas Sankara spoke in front of the UN General Assembly as the leader of the newly christened nation of Burkina Faso. There at the center of global capital, he gave his most visionary speech of the world he wanted to build, a world where nations are not economically shackled to their former colonizers, where the struggles of the working class in the first world are seen as the same as newly liberated nations struggling to determine their own destiny. The international order of western capital extracting wealth from the workers of the global south, hollowing out the planet for profit, and endless wars that Sankara sought to dismantle has only become worse. Perhaps it's time to look at the world that Thomas Sankara wanted us to fight for. Imperialism Is On Your Plate“Now our eyes have been opened to the class struggle and there will be no more blows dealt against us. It must be proclaimed that there will be no salvation for our peoples unless we turn our backs completely on all the [economic] models that all the charlatans of that type have tried to sell us for 20 years.”[2] People remember Sankara for his many stellar achievements: vaccinating 2 million kids; planting 10 million trees; and achieving national food self-sufficiency, to name a few.[3] However, it is crucial we remember that Sankara saw these massive public projects as more than just a series of generous social programs, but instead as a step towards national liberation. The 1950s and ‘60s saw a wave of African nations gain independence from Europe’s empires. However, these new post-colonial leaders soon realized that political independence did not necessarily mean economic independence. Most European colonies were deprived of the means to invest in a sizable manufacturing industry, let alone an industrial base, in order to act as a cheap source of commodities for Europe’s industrial economy. Thus the first task for many post-colonial nations was to modernize their economies, which they found to be possible only by using loans and skilled labor from the empires they sought independence from. European nations and the global north in general used debt to force post-colonial nations to maintain the same economic relationship that existed during the colonial era. Some have called this system “neo-colonialism,” others, such as Vijay Prashad, maintain that it’s the same imperialism that Lenin railed against in 1917. In Burkina Faso, one of the most overt examples of neo-colonialism strangling the Burkinabe’s desire for self-determination was foreign aid, an institution that continues to plague the African continent. Sankara resented how foreign charities never offered their aid without strings attached. Burkinabes found it humiliating, that in a mostly agrarian nation, they were forced to depend on the global north for food. Sankara’s drive for food self sufficiency was driven partly by a desire to do away with the west’s paternalistic attitude towards the Burkinabe. Sankara stated bluntly, “Some people ask me, “but where is imperialism?” Just look into your plates where you eat.”[4] This is why Sankara’s lesser-known project of resurrecting the traditional dress, the Faso Dan Fani, might be his most revolutionary. Like food, Burkina Faso imported much of it’s garments, western clothing was especially popular among the bureaucratic class. Sankara’s government instituted a national campaign to shift from foreign made clothes to manufacturing traditional Burkinabe clothes through female-led cooperatives that sourced their cotton from Burkinabe farmers, breaking one of the biggest economic taboos--that modernization required liquefying the peasantry to produce a cheap surplus of commodities and labor. Previous modernization projects in the continent typically came at the violent expense of local communities. One of the most notorious examples was the construction of the Kariba Dam, a 420 foot tall hydroelectric dam that displaced 57,000 Tonga people in modern day Zambia and Zimbabwe. Sankara did not want to replace the foreign capitalist with a domestic one, and he proved that modernization can benefit the existing farming population and workers in newly emerging manufacturing industries. The campaign to revive the Faso Dan Fani was an immensely successful one, going from a nearly non-existent light industry to generating a million dollars in revenue by 1987.[5] While the Faso Dan Fani campaign was not necessarily an industrial project, it was crucial to diverting cotton from low income export to an income generating domestic industry with an indigenous consumer base. If the Sankaran revolution was not cut short after four years, the Faso Dan Fani campaign could have evolved into a thriving textile industry on par with modern day Vietnam. We Feel On Our Cheek Every Blow Struck Against Every Other Man In The World“I speak not only on behalf of Burkina Faso… but also on behalf of all those who suffer… those millions of human beings who are in ghettos because their skin is black… those [indigenous Americans] who have been massacred, trampled on and… confined to reservations… women throughout the entire world who suffer from a system of exploitation imposed on them by men… I wish to stand side by side with the peoples of Afghanistan and Ireland, the peoples of Grenada and East Timor. We wish to enjoy the inheritance of all the revolutions of the world.”[6] Sankara’s vision reveals that nationalism can transcend nations itself. When he came to power, Burkina Faso still maintained its colonial name, Upper Volta. Sankara invented the name Burkina Faso, which translates to “the Land of the Upright People,” by combining the languages of three main ethnic groups in the country. Sankara himself was Silma-Mossi, a social minority, a fact that Compaore, who was a member of the larger Mossi population, would unfortunately exploit in 1987.[7] Today, nationalism is often associated with ethnonationalist projects, such as Israeli apartheid or American nativism, but to Sankara and many anti-colonial leaders, nationalism was seen as a collective project for the self determination of all oppressed peoples. Sankara truly understood the internationalist element of self determination. In his speech to the UN, Sankara does not simply declare solidarity with liberation movements abroad; he declares that they are fundamentally the same struggle. Sankara connects the struggles of the black ghettos in the US to the Palestinians’ struggle against Israeli occupation to Black Africans’ struggle against the apartheid regime, by framingt each struggle through the neocolonial system.[8] His speech was an elaboration of his Third World politics. While Third Worldism is often vulgarly interpreted as denying the working class in the global north as part of the international proletariat, the third world movement at its height was far from promoting this idea. Right before he gave his speech to the UN, Sankara visited Harlem, where he told a crowd of several hundred African Americans that “our White House is Black Harlem.”[9] Sankara was not an outlier on this front. Revolutionary socialist organizations in the United States, such as the Black Panther Party, Gidra, and CAVAS, used Third Worldist analysis to identify issues unique to the communities they organized.[10] Sankara did not see the working class of the developed world as enemies, but correctly concluded that the liberation of at least some segments of the working and underclass in the global north was fundamental to ending US imperialism and global capitalism. Sankara also did not tolerate “the internationalism of fools. He viewed corruption and abuse committed by post-colonial leaders as maintaining the old colonial system. During his brief tenure, Burkina Faso became a haven for foreign activists and dissidents. In 1987, Burkina Faso hosted the Bambata Forum, where Pan African and anti-apartheid activists discussed how they can mobilize support for SWAPO and the ANC, which were then engaged in armed struggle in Namibia and South Africa.[11] Burkina Faso’s active foreign policy terrified their former French overlords, who in 1986 brought Jacques Foccart back into government. Foccart, also known as “Mister Africa” for his role in maintaining France’s colonial regime, used his former colonial network to rally allied African leaders to isolate the spread of Burkina Faso’s revolutionary ideas. Sankara had no qualms publicly calling out post colonial leaders in the Francosphere who were willing to maintain the colonial status quo. One of Foccart’s allies, Houphouët-Boigny, established contact with a high ranking Burkinabe officer who was wary of Sankara’s aggressive anti-corruption drive. That officer was Blaise Compaore.[12] Kill Me And Millions Of Sankaras Will Be BornThere are two lessons we can learn from Thomas Sankara’s vision for a “new international economic order.” The first is that anti-imperialism must be anti-capitalist and vice versa. Using the same means that colonial powers and corporations used to exploit the working and oppressed classes will only recreate those same relationships. The greatest threat Sankara posed to global capital was not his support for Cuba or SWAPO, but his willingness to launch modernizing programs on behalf and not at the expense of Burkina Faso’s peasantry and working class. Food self-sufficiency, textile cooperatives, and mass vaccinations threatened to expose an alternative to the neocolonial system of debt and foreign aid that wealthy nations are all too eager to maintain. Sankara’s premonitions would tragically turn out to be true. By 1987, Foccart had succeeded in isolating Burkina Faso from most African nations in the Francosphere, and overzealous and opportunistic purges by the Committees in Defense of the Revolution (CDR) alienated them from the communities they sought to represent, which would eventually culminate in Blaise Compaore seizing power in what was most likely a French-backed coup. Compaore would reverse most of Sankara’s reforms, leaving the country in much the same position it was in 1983. Today, Burkina Faso faces an ecological crisis of desertification, millions struggle with food insecurity, and the people are once again heavily dependent on foreign aid.[13] However, even with a three decades long attempt to erase his memory, Sankara’s legacy refuses to die. During the 2014 uprising that finally overthrew Compaore’s regime, protesters defiantly held up portraits of Sankara, who had become a popular symbol among a generation that was not even alive to witness Sankara’s revolution.[14] What we should all take away from Sankara’s revolutionary four years is that the struggle for self-determination must be an international one. Sankara understood Burkina Faso’s independence could not be possible if the system that exploits the working class in both the global north and south. Sankara envisioned a “new international order” because he believed that was the only way to preserve and expand Burkina Faso’s achievements from the neocolonial counterrevolution. Now that Thomas Sankara is back in the spotlight, one way we can preserve his public memory is to show that his vision of the world can still become a reality.

Bibliography Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

AuthorJay is a Korean-American, who has lived in South Korea, Vietnam, and the Midwest and East Coast of the United States. While studying in Iowa, he became a student organizer for a statewide organization fighting for Free College for All and co-founded the local Students for Bernie chapter, which is now a chapter of the Young Democratic Socialists of America. Jay is also one of the hosts of Red Star Over Asia, a podcast which interviews organizers, academics, and journalists on politics in the Asian continent from a socialist perspective. Archives May 2021

0 Comments

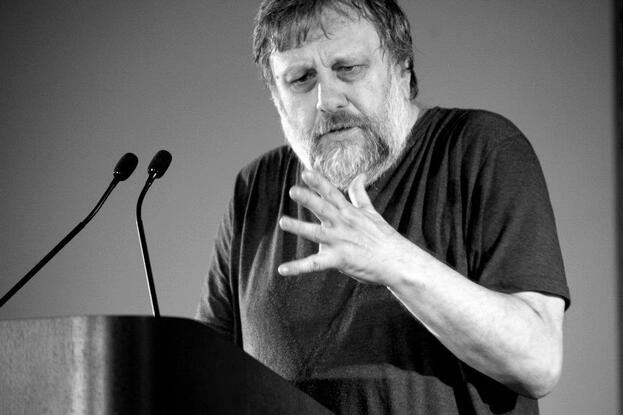

5/13/2021 Book Review: Did Somebody Say Totalitarianism? By Slavoj Žizek (2001). Reviewed By: Harsh YadavRead Now"Freedom in capitalist society always remains just about the same as it was in the ancient Greek republics: freedom for the slave-owners." - Vladimir Lenin. Why am I quoting Lenin in a book about totalitarianism? Because he is a figure who propounds a very germane exegesis of the liberal democracy model which is acknowledged today as a symbol of prosperity and peace. Lenin called it the dictatorship of the bourgeois, rule of the capital, or rule of the upper class where there is only freedom for the slave owners. Whenever someone says Totalitarianism, several thoughts surface to the mind of the individual. They think about various governments that have restricted the rights of the people, took part in vanquishing opposition and fear-mongering, control all aspects of life for complete subjugation to authority by controlling mass media to spread propaganda. Totalitarianism became a political ideology with the advent of Fascism. Mussolini believed that the Corporate State is totalitarian and also wrote a book on it titled ‘The Corporate State’. Any individual interest or whatsoever was out of harmony with the interest of the State. The State corrals all of society. The idea that totalitarianism is integral political power that is exercised by the state was contrived in 1923 to elucidate Italian Fascism as a system that was fundamentally different from conventional dictatorships. Totalitarianism is not at all predictable and, in many instances, it's not even conspicuous. According to the dictionary, Political science is the branch of knowledge that deals with the state and systems of government or the scientific analysis of political activity and behavior. A policy state or system can be interpreted in many different manners. So political study is subjective and open to many interpretations but ignorance moves it to the objective side. This is what Žižek discusses in the book about totalitarianism. how it has been reduced to just a few interpretations and the fact that liberals don’t want to talk about what they call a ‘demonic’ political idea and denounces as ethically dangerous. Totalitarianism as an ideological concept has always had an explicit strategic function to guarantee the liberal-democratic hegemony by dismissing the Leftist critique of liberal democracy as the perfidious or Janus-faced of Right-wing dictatorships. Žižek looks at totalitarianism in a way that Wittgenstein would approve of, finding it a cobweb of family resemblances. Žižek reveals the unison view of totalitarianism, in which it is defined four ways: the holocaust as the ultimate, diabolical evil and beyond any political analysis; the Stalinist gulag as the alleged truth of the socialist revolutionary project which refutes socialism and radical progressive thoughts as they call it utopian and believe that utopian vision leads to totalitarian realities; the recent wave of ethnic and religious fundamentalism to be fought through multiculturalists tolerance; and the deconstructionist idea that the ultimate root of totalitarianism is the ontological closure of thought. Žižek starts the book by telling that trounce of the left is not because of the inanition of the intellectual resources but because of its ideological defeat against liberalism. The radical left is trapped in a facile opposition between the rhetoric of liberal democracy on the one hand and totalitarianism on the other. The book explains the psychoanalysis of the concept of Totalitarianism. Žižek can be called the seer of Lacan as his ideas drew heavily from Hegel’s Idealism and Lacan’s psychoanalysis and that’s why the book is more of a psychoanalytic study of totalitarianism than political. Lacanian psychoanalysis in itself is an intricate topic to comprehend, the book might help some to look at it in a clear sense. It’s important to understand Lacan to discuss liberalism as he believed that no matter how democratic we may be, we are always attracted to authority figures. We simply don’t want to take charge and want someone to lead. This concludes that Liberal democracy is still a rule of the insignificant minority over the significant majority and is less about representation and leads to the polarity of the power. Žižek in this book calls the discourse on totalitarianism pertinent because it helps to discern the shortcomings of the modern democracy but the problem he calls out is the misuse of the notion as any argument regarding it is rejected by calling it evil and this thwarts the intellectual development of the society giving rise to centrism which believes that any change in the status quo will eventually lead to totalitarianism. Žižek examines these ideas and concludes that the devil lies not so much in the detail but in what enables the very designation totalitarian: the liberal-democratic consensus itself which remolds itself into fascism in no time as it is governed based on capital. Authoritarianism is not pretending anymore to be a real alternative to the flawed democracies everywhere, but we can see many more authoritarian practices and styles being smuggled into democratic governments. Liberalism is a more sophisticated version of authority that is not about freedom and it can be best fathomed by studying Gramsci. In a totalitarian society the ruling class tells you to do this particular thing, in liberal democracy Ruling class through various institutions like family school, religion familiarizes us with rules and behavior and natural respect for the ruling class while maintaining a delusion around ‘Free Speech’. This is what Žižek in his lectures call the ‘Paradigm of modern permissive authority’. Regardless, Žižek raises interesting points. Does real democracy come only as an unanticipated paroxysm of ethical duty? Is the marking of diversity enshrouds totalitarian thought? Does magnum opus result from excessive knowledge? Do deeds emanate from prevailing ethical materiality or do they create it afresh each time they occur? Do cultural studies reveal the shapes of global hegemony? There is one point that Žižek misses out; the conflict between the divergent ideologies is not only because of the parochialism of liberal democracy but also the altercation between the Enlightenment and Counter-Enlightenment thoughts. Progressive politics is the outcome of Enlightenment thoughts which is the intellectual legacy of Marx that values freedom and equality. This is not an easy book at all. This is meant for research scholars. I (a chemistry Hons student) had difficulty reading but was able to complete this because the pop culture references made it very engrossing for those who are aware. I'll recommend it for those who want a different and very deep perspective of the liberal democratic model and good work on Lacanian psychoanalysis. AuthorHarsh Yadav is from India and has just recently graduated from Banaras Hindu University with a Bachelor of Science degree in Chemistry. Harsh is a Marxist Leninist who is intrigued by different Marxist Schools of Thought, Political Philosophies, Feminism, Foreign Policy and International Relations, and History. He also maintains a bookstagram account (https://www.instagram.com/epigrammatic_bibliophile/?hl=en) where he posts book reviews, writes about historical impact, socialism, and social and political issues. ArchivesWhat is a group? It may seem silly to even ask such a question, especially as a leftist. After all, we speak in terms of groups all the times, and, as Marxists, especially of the struggles between them. For example, we speak of the struggle between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, the struggle between the patriarchy and women, or the struggle between white supremacists and oppressed racial groups. These are just three out of the many ways in which we speak of group struggles, and it seems that such language is vital to addressing the material needs of every person. Without the language of intersectionality, it seems practically impossible to rectify the countless injustices perpetrated against oppressed people. While a still enormous task, the language of intersectionality at least gives us a plausible way to address the needs of all people. But, again, what is a group—the unit of classification that the language of intersectionality is built upon? A group is an abstraction. If I speak of the group of the bourgeoisie, I speak of the set of people who own a sufficient amount of the means of production such that they may subsist solely on the ownership of those means of production through others’ labor. Now, this set only “exists” as an abstract object. Consider the proposition “No one person can enumerate every member of the set of ‘the bourgeoisie.’” This proposition is extremely probable, if not actually true. If there are any such people, they are certainly few and far between. Clearly, however, this set still objectively obtains in our social world. The set still “picks out” all of the members whether or not any individual person can. I use scare quotes here because the set does not do anything at all; i.e., the set is not an agent capable of doing, the way a physical agent is capable of doing. To articulate even further, the set qua set is not capable of doing work upon the physical world. Only the set as understood by some competent agent is capable of being causally implicated in any work done on any physical systems. As should be obvious, except in the extraordinarily rare case of someone actually being able to enumerate every member of some set, the set as understood will be a distortion of the set qua set. So it seems, then, that the bourgeoisie, qua bourgeoisie, cannot causally impact the physical world. I am aware that this seems entirely anti-Marxist, but the reader must follow me with precision. If all groups are sets, and no sets can do work, then no groups can do physical work. If something cannot do physical work, then it cannot do anything. So no groups can do anything. However, individual persons acting qua member of some group can really do things. So, while we cannot (strictly speaking) say “The bourgeoisie exploits the Global South” we can say “The members of the set ‘the bourgeoisie’ exploit the members of the set ‘the Global South.’” Through this clarification we ground the action, exploitation, to where it actually occurs; viz., in the lives of the exploited. Now this may seem to be “mere” semantics, but it is vitally important. Well-meaning leftists are becoming increasingly focused on analyzing situations entirely through group analyses. As we have seen, however, talk of group “action” is simply shorthand for the actions of the members of the group. To entirely subordinate the individuals involved in favor of the idea of group “agents” is to lose sight of who is actually being oppressed. Let us hone in on the issue of racism as a clear example. Racism is evil precisely because it negatively affects non-white people. It is not evil in virtue of the group, or the set, of non-white people being negatively “affected" by racism. The only way a set can be “affected” is if the quantity of objects belonging to it increases or decreases in the actual world. While one could say that, technically, the set of “Black persons,” for instance, does decrease with the ongoing and horrendous racist police killings in the United States, it seems disrespectful to those killed to say that the reason their murders were evil is because they caused a numerical decrease in the set of “Black persons.” In fact, those murders were evil because they killed those people, because they affected those people. We care about groups insofar as they are composed of people. Now, why has all of this discussion been even remotely relevant? It is because many on the left, many who even consider themselves Marxists, have abandoned a materialist ontology in favor of Hegelian mysticism. In fact, “reductionist” has become a scare-word among many leftist circles, even though materialism itself is a fundamentally reductionist ontology. In fact, what is unique about Dialectical Materialism is the appropriation of Hegel’s dialectic mode of thought to a materialist conception of reality. While the term “Dialectical Materialism” is not one Marx actually coined, it is an apt name for the way we must approach our philosophy. The qualifier is “Dialectical” and the root is “Materialism.” What we do, then, as Marxists, is to move from our reductionist root, which seeks to explain the world in material terms, to our Dialectical analysis of persons with the material world. However, the strict materialist will always acknowledge that in principle all of these interactions reduce to the material interactions at play. So groups like the bourgeoisie, white supremacists, sexists, homophobes, transphobes, etc., are not agents. When we speak of these groups “doing” things, we must remember that our language there is shorthand for the real, material interactions of individual persons with their environments—because that, at the end of the day, is the location of the material, or real, dialectic process. AuthorJared Yackley is an undergraduate student of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley. With his primary focuses in epistemology, history, and political philosophy, Yackley hopes to apply the principles of dialectical materialism to contemporary issues both philosophical and political. |

Details

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

About the Midwestern Marx Youth LeagueThe Midwestern Marx Youth League (MMYL) was created to allow comrades in undergraduate or below to publish their work as they continue to develop both writing skills and knowledge of socialist and communist studies. Due to our unexpected popularity on Tik Tok, many young authors have approached us hoping to publish their work. We believe the most productive way to use this platform in a youth inclusive manner would be to form the youth league. This will give our young writers a platform to develop their writing and to discuss theory, history, and campus organizational affairs. The youth league will also be working with the editorial board to ensure theoretical development. If you are interested in joining the youth league please visit the submissions section for more information on how to contact us!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed