|

How is a man defined by the materials in which he possesses? How does a man’s physical labor become embodied in the objects he owns? On pages 278 and 279 of Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison examines how the material reality that surrounds his unnamed narrator and the characters around him upholds the ideas of an unchanging human nature that leads to the domination of racial and class hierarchies. Ellison explores the intricate relationship between a man’s labor and its products of physical materialism, dialectical struggles between the “law” and the “law abiding”, and the notion of dispossession. In context, the unnamed narrator is living on edge every single day in Harlem, New York. Not only for the color of his skin, but of his constant struggle dealing with expulsion from school and the struggles of finding identity within the concrete jungle of New York. He is dirt poor and spends his days working at a paint factory in which Ellison purposely structures it as a representation of class struggle confined within the floors of the building. This symbolic examination is as well present in the passage above. Ellison begins by establishing the role of the man in which he is the victim of a passive aggressive act of eviction in which a group of armed men, from the orders of a landlord, throws out a family’s belongings in the middle of the street, disturbing the surrounding scenery of the city. The local folks begin to grow discontent with the acts from the armed men and begin pleading for sympathy. Thus, the narrator jumps into the scene, eager to utilize his passion for speaking, and begins to rile up the crowd (unintentionally). The narrator begins by asking the male evictee of his employment status. He makes this decision because the narrator is attempting to humanize the man and give him an identity in which the crowd can define him, sympathize him, and emotionally connect with his situation. Therefore, by going a humanistic route, the narrator is successful in giving the random evictee recognition from the crowd as an active member of the community. The evictee responds by establishing himself as a “day laborer”. This ultimately gives an insight as to the shared conflict in which the evictee and the community as a whole go through together. By directly acknowledging the existing struggle of the evictee, the struggle of the people of Harlem becomes embodied by the evictee. The narrator then uses a simile in comparing “his stuff strewn like chitterlings in the snow?” and then metaphorically compares the evictee’s “stuff” to his “day labor” by exclaiming, “where has all his labor gone?” First, by comparing his “stuff” to “chitterlings in the snow”, the narrator gives the image of a literal interpretation of a “pigsty”, as the objects on the ground are scattered like trash. Also, the narrator being from the south, it is very interesting how he uses his southern identity in the use of figurative language. It allows an oddly specific comparison that only those within the community might understand (I myself had no idea what chitterlings were before researching). Given the status of his day labor, the accumulation of the hours of labor the man had put during his lifetime are symbolized by his objects scattered on the sidewalk. To have a marshal drop by the apartment and throw out one’s “labor” so effortlessly and uncourteously symbolizes the conflict of class and racial struggle of the day laborers of Harlem, and to that thought, the people in the crowd continue to identify with the struggle of the evictee. Continuing, the narrator then uses the age of the evictee, eighty-seven years, as a means of given his materials a reference of time in which they have been accumulated. “Look at his old blues records and her pots of plants, they’re down-home folks, and everything tossed out like junk whirled eighty-seven years in a cyclone. Eighty-seven years, and poof! Like a snort in a wind storm”. This accumulation of material possession reflects the labor and livelihoods of the people who possess them. Ellison portrays the action of the men’s carelessness in the materials of the evictees through simile and hyperbole. By comparing “everything tossed out like junk whirled eighty-seven years in a cyclone,” Ellison gives a hyperbolic sense of the scenery as if a cyclone had passed by and whirled the evictee’s “junk” around the proximity. Comparing the materials to junk is intriguing; as if the narrator is giving the idea that by which he first gives the objects a sense of humanity at first, giving the idea of the “pots of plants” that defines the evictee’s identity as “down-home folks”. However, this is contrasted when the evictors get their hands on them, instantly transforming them into “junk”. It is assumed that Ellison is attempting to define humans by the materials they possess; or could it be vice versa? By exploring this duality, Ellison is successful in drawing the questions as to the nature of the “day laborer’s” relationship with his material possessions. Therefore, it is inferred by Ellison that ideas cannot exist separate from their material conditions that exhibit such ideas. Next, Ellison tackles the internal contradictions between the “law” and the “law abiding”. The marshal, being metaphorically given the title, “law”, has been indicated by the narrator of being unjust. He infers that when the “law” acts lawless, it is permissible for the “law-abiding” to speak its language. “Remember it when you look up there in the doorway at that law standing there with his forty-five. Look at him, standing with his blue steel pistol and his blue serge suit, or one forty-five, you see ten for every one of us, ten guns and ten warm suits and ten fat bellies and ten million laws. Laws, that’s what we call them down South! Laws! And we’re wise, and law-abiding,”. Ellison also uses imagery and repetition of the color “blue” and the “forty-five” (referring to the pistol) to give an image as to whom the “law” is defined. Just as how the evictee was defined by the materials in which he possessed; the “law” is defined that way as well. Interestingly, Ellison develops the concept of the negation of the negation. In this circumstance, the evicted run into their opposites (the evictors) in the course of development. The evicted cannot fully develop in their bloomed potential as they have become ousted by those who possess the keys to their metaphorical “apartment”. Ellison also provides the negation of the negation within the relationship of the marshals and the African American community. The marshal disregards the “objects” (in this circumstance, the material possessions of the evictees. In the metaphorical sense, the development of culture and identity in which the materials were produced and influenced by) as junk, leaving the community continuing to struggle to objectify their identity. In this specific circumstance, the wife of the man, wants to pray in her home one last time. She possesses a Bible, and requests one last wish. She is in a sense, defined by her passion for the Bible, and vice versa. The narrator knows this and utilizes it to his advantage. By exclaiming the words of scripture, “blessed are the pure in heart”, the narrator then is able to ask the question, “what’s happened to them? They’re our people, your people and mine, your parents and mine. What’s happened to ‘em?”. By identifying the couple of evictees as part of the community, the narrator continues to allow the crowd to see themselves in the footsteps of those victimized. Their response, however, gives the reader an interesting word that clearly defines the interconnectedness of the material possessions, what they define, and what the couple represents- dispossessed. To dispossess means to deprive someone of land, property or other possessions. Intriguingly, an ambiguous question emerges- who is being disposed in this situation? The evictees? The materials? The community? In a sense, all of these assumptions are correct. A person in the crowd introduces the term “dispossessed” and the narrator then says, “Dispossessed, eighty-seven years and dispossessed of what? They ain’t got nothing, they can’t get nothing, they never had nothing. So who’s being disposed? Can it be us? These old ones are out in the snow, but we’re here with them. Look at their stuff, not a pit to hiss in, nor a window to shout the news and us right with them… They’re facing a gun and we’re facing it with them. They don’t’ want the world, but only Jesus… How about it, Mr. Law? Do we get our fifteen minutes worth of Jesus? You got the world, can we have our Jesus?” We have already examined the interconnected relationships between material possessions and those who possess them. Now it is next to examine how does one react when they have been dispossessed from their materials. The narrator infers that the evictees have already been dispossessed, and that they have handed their “world” into the hands of the marshal, who acts as an interpenetration of opposites. He becomes the facilitator that blurs the line between the evictors and the evictees. The people only want “fifteen minutes of Jesus” but the marshal cannot allow due to his “orders” and threatens to shoot anyone who approaches the apartment. The narrator then continues by referring back to the symbolism and imagery associated with the color “blue”, saying “with his blue steel pistol and his blue serge suit. You heard him. He’s the law. He says he’ll shoot us down because we’re a law-abiding people. So, we’ve been dispossessed, and what’s more, he thinks he’s God. Look up there backed against the post with a criminal on either side of him.” By again referring to the dialectical relationship of the “law” and the “law-abiding”, the narrator is able to then legitimize the calls for the people to respond to the lawlessness of the law in its own “language”. He has successfully riled up the crowd, and they begin the process of repossessing what had been stolen from them- identity. The narrator operates in an assertive and sincere tone. He is fed up with the “dispossession” and “displacement” of his people, and he utilizes his speaking ability to finally draw the final straw. By examining the relationships of a man’s labor and the materials he possesses, the dialectical relationships between the “law” and the “law abiding”, the “evicted” and the “evictor”, and the weight the word “dispossession” possesses in the circumstance of the evicted family and of the African American community, Ellison is able to whip up a narration that leaves those who listen with answers and motivates an act of reclaiming what is being taken away from you. We shall overcome our eviction by bringing consciousness to the evicted of their dispossession and displacement and bring about a synthesis of a new apparatus. Endnotes: (1) Ellison, Ralph. Invisible Man. New York :Vintage International, 1995. AuthorJacob Masterson is a looming political science major at an undecided college. He currently specializes in Marxist political philosophy, radical social movements, and American history. Archives August 2021

0 Comments

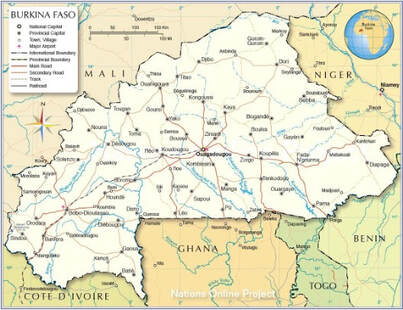

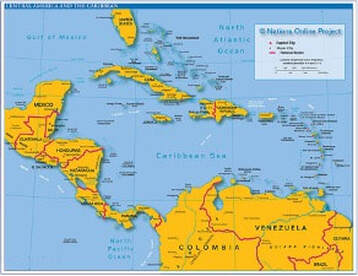

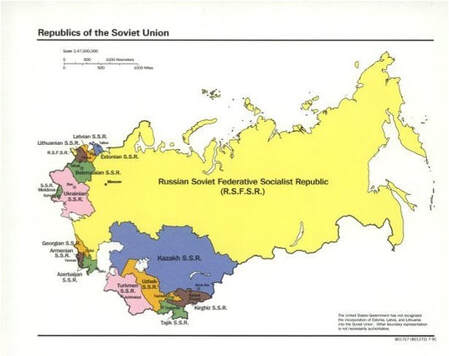

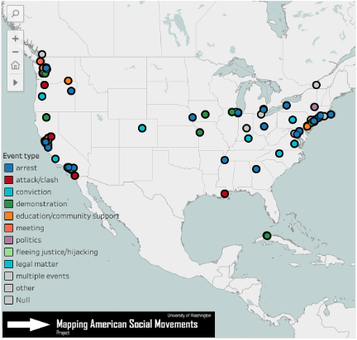

I recently wrote and presented to the people of Mount Desert Island on the delimitation of lighthouses and spaces islanded literally and physically from the “outside” world. The essential premise was on how lighthouses and more broadly spaces islanded from the rest of the world could represent existences that were more isolated by their own volition. Spaces, where we can ultimately see our own Covid19-dictated lives mirrored more satisfyingly. But this also presents a larger question on delimitation in Marxist Revolutions. Immediately we think of the island of Cuba, the relatively small country of Burkina Faso, or the big mass of the Soviet Union. How does an area’s delimitation affect its revolutionary aspirations? And if we look at this from a Marxist perspective we unquestionably have to include the legacy of imperialism. How do countries delimited by their physical boundaries in addition to their economic and social brutalization from imperialism shape out compared to a country not affected by this violence? To break this down let’s look at delimitation narrowed into two different categories. The first one being the physical, geographic delimitation of a place: its global location, if it is islanded, its indigenous history, and its ability for natural resources. The second form of delimitation that I want to look at is its delimitation in the eyes of imperialism: how a place’s boundaries and limits were forced by the imperialism of a western country. For the purpose of this examination I will not be looking at the Marxist Revolutions of all countries and places but rather focus on a few: Thomas Sankara’s work in Burkina Faso, the work of Castro and Guevara in Cuba, the huge impact of the Soviet Union, and more abstractly the Black Panthers in the United States. Thomas Sankara and Burkina Faso: Burkina Faso’s global location is important. Located in the western part of Africa, it has a dry and tropical climate. (Burkina Faso National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) Official Document (French) - November 2007) More broadly Burkina Faso’s legacy sits among the colonization of the African continent, along with being an example of US military intervention. Importantly, it is landlocked, with no access to the sea, although the country enjoys a rich history of farming which Sankara helped to expand among his vast reforms. The first people to settle in the area were the Mossi people in the 11th and 13th centuries. Their expansive kingdoms were important in the Sub-Saharan trade. In 1890, it was colonized by the French who would start their process of exploitation. (SAHO) Currently, the gold mining sector has colonized and exploited the country and its people in post-Sankara society. Much like other countries on the African content, Burkina Faso is extremely diverse in its peoples, languages, cultures, and traditions. The French forcibly created these non-contextual borders, languages, religions, and economies that had no relationship with the existence of the peoples on the land before. The brutalization of the people of Burkina Faso is a prime example of just how long-lasting the violence from imperialism reaches beyond its effects on people but on boundaries as well. We can see some inherent delimitations in the country. Its borders and resources make it vital for relationships with other nations; other nations who could (and did) choose to exploit and brutalize the country for its self-determination and bold commitment to liberation through Marxism. Those who took Sankara down were bribed by western interests (or the literal interests themselves), his demise can be seen as a product of the inherent and forced delimitation of the country. Sankara was not in the position to shut out the entirety of the world, erase the lasting effects and people from the nation’s origin in colonization, and/or refuse foreign aid. The natural delimitation of the country’s geographic position in West Africa also reveals delimitation through imperialism. The Western powers (France) that colonized the land were ultimately the ones that had control of the boundaries and foundations of the country. Yet in some ways, delimitation helped Burkina Faso even have some sort of Marxist revolution. Its smaller geographic area enabled Sankara to communicate better with the entirety of his people. The long tradition of farming and farmers in the area helped to push Sankara’s reforms. And lastly, if we see delimitation as the action of fixing a limit, we could say that Burkina Faso was more open to delimitation beyond borders and boundaries but among new ideas and political ideals. The historical legacy of imperialism created a need for a revolution in the first place, which is why we see examples of left-wing revolutions in countries brutalized by imperialism so often. Che Guevara and Fidel Castro in Cuba: This leads us to another example of a smaller country whose people were forced to endure colonization and imperialism by Western powers. Cuba’s geographic delimitation though is a little different. In some ways its position as an island helped the country: one small reason why the Soviet Union allied with the country was the Soviet Union’s affinity for water access. Another element is the lasting effect the tourism industry would have on Cuba pre and post-revolution. Cuba was exploited by imperial powers for its warm climate through the tourism industry before Castro led the proletariat to fight against the imperial powers. Or even before in the climate’s ability to produce sugar. And tragically we can see how the physical delimitation of an island would be hurtful to a revolution unpopular by the global-capitalist powers: after the fall of the Soviet Union, Cuba would struggle to feed its people because of the inherent inability to be completely self-sufficient in its food production (which should not be, and is not, expected in any other countries). Yet any young Marxist first learns about Castro and Guevara who in the Sierra Maestras quite literally fought hand and tooth for Cuba’s independence. The ruralness of the island allowed the comrades to ally themselves with farmers spread out from the city center of Havana. We can see then how Cuba’s geographic delimitation first enabled its revolution to happen. Without the cover of the Sierra Maestra and that guerilla warfare, the revolution possibly wouldn’t have happened. But as I mentioned before, in a world where those who reject global capitalism are isolated, inhumanely ostracized, and invaded, an island’s inherent smallness and singular climate made the revolution hard to sustain. If our global picture wasn’t delimited by the constraints of capitalism perhaps Cuba wouldn’t have run into the problems that it was forced to confront in its extremely limited boundaries. (Map from Nations Online) The Soviet Union: Along with the vastness of the Soviet Union’s geographic territory comes even more delimited history; therefore only a few examples will be examined here. As I mentioned before: one of the favorite topics of any high school history teacher is undoubtedly the lack of sea access that the Soviets had. This forced the dynamic of many of its expansion efforts, policies, and relationships with other countries (oftentimes those countries had been brutalized by Western, capitalist powers). Water would also encourage boundaries to expand; the soviets used the power of natural water resources to further their industrial development. (Tolmazin). In fact, there is a longstanding history of the Soviet’s appropriation of natural water resources which unfortunately hurt a lot of natural water climates, although the Soviets have added invaluable scientific research in understanding the impact of harnessing water likewise. Water is not the only resource the Soviet Union used in its delimitation. I find it important to reflect on not only the geographic position but its size. Geographically its located centrally quite literally between two huge continents: Europe and Asia. Among conflicts and wars, its boundaries and borders were challenged physically, forcing the Soviet Union to henceforth physically respond. This also added to different cultural, social, and linguistic barriers. One specific tidbit that exemplifies this is that in 1914 Vladimir Lenin ruled against a compulsory or official state language after the October Revolution (Comrie, Bernard (1981). The Languages of the Soviet Union. Cambridge University Press). Perhaps it is in understanding the delimitation (or lack thereof) of the Soviet Union where we can best observe these crowning moments. I will though say that a country with less delimitation in the form of extensive boundaries with less physical land area definitely helped the Soviets. Not to mention the Soviet Union’s legacy with imperialism and colonization is obviously way different than places such as Cuba or Burkina Faso. In this way, we can see that the legacy of delimitation from western imperialism in the form of colonizing an independent group of people is less evident and that undoubtedly helped the Revolution to at least exist on a bigger global scale. And lastly, the sheer amount of people under the Soviet Union is the biggest example of delimited space in a Revolution. Although countries like the United States were undoubtedly scared of the Marxist tendencies of mainly Cuba but also Burkina Faso, the threat the Soviet Union would pose in the neoliberal eyes of the Americans was enormously grand. (Map from Library of Congress) Black Panther Party in the United States: Lastly, I wanted to include the effects of delimited spaces in the Black Panther Party. Like the expanses of the Soviet Union, the United States is bigger than the two other countries we previously looked at. No matter how talented the revolutionary, the distance between say Fred Hampton in Chicago and the headquarters in Oakland was immense. This idea of delimitation was something Hampton invariably battled with before he was murdered: how can one focus so closely on the dynamics and lives of their community while also fighting for country-wide, revolutionary change? Malcolm X in much of his autobiography talks extensively about the travel required in his work, and how that changed his overall message. He would assign positions to specific leaders already embedded in their communities because he understood the importance of that local understanding. Tyner writes in “Defend the Ghetto”: Space and the Urban Politics of the Black Panther Party: “Black communities in the North, far from being in disarray and plagued by dysfunction, waged a protracted fight for justice and equity but constantly had to contend with theories and policies that blamed them for their condition (Theoharis 2003, 7). Theoharis explains that rural, southern African Americans were seen as emblematic of long-suffering struggles, whereas the urban-based African Americans were portrayed- in the media, in academia- as pathological…” So then not only the delimitation of state-created geography is important to acknowledge but the actual cultural differences between our cardinal directions. The Black Panthers had to contend with not only the systemic racism under capitalism that they were fighting against but the geographic and boundary-based realities of that same system: capitalism. It is hard for me to see how the inherent delimitation of the United States helped the Panthers. I guess the beauty of unique and niche communities comes from their ability to grow optimistic revolutionaries: not yet scarred from the realities of far-reaching suppression. Perhaps then, that was the one way in which delimitation helped the Panthers: it created the ability for sanguine leaders to at least, attempt to rise void of the suffocating reality that a state with all the power and money in the world would simply continue to suppress through every means necessary. (Map from Black Panther Party History and Geography) There are a vast array of other countries with left-wing revolutions that we could talk about in terms of the role of delimitation in their fight. Equally, there are heaps of small lessons we can see in those countries: is Uruguay’s current left-leaning government more successful because of the lack of indigenous people to be exploited; the country couldn’t be built on that original sin of exploitation and is therefore built on a system of less bloodshed? How has the exploitation of the global south by Nordic countries created systems less pure in their supposed left-leaning morality? How has the legacy of the United States-caused wars created the ability for socialist continuations in the Vietnamese government? The point of course is that we can see moments where delimited spaces gravely impacted Marxist Revolutions on all global levels. So much like how we analyze small spaces of urban planning in our cities and communities, I wonder what the impact of looking at the role of delimitation in larger and more abstract processes of Marxist Revolutions could reveal. From Graduate Hospital, Kensington, and Fairmount in my local Philly, to these larger spaces such as Cuba and Burkina Faso that I analyzed before, the role of white supremacy, neoliberalism, and global capitalism is ginormous. From gentrification to lack of land to farm, the space, boundaries, and borders of an area can divulge telling lessons on some of the biggest Marxist Revolutions. Bibliography: Black Panther Party History and Geography - Mapping American Social Movements. https://depts.washington.edu/moves/BPP_intro.shtml. Accessed 18 Aug. 2021. Burkina Faso | South African History Online. https://www.sahistory.org.za/place/burkina-faso. Accessed 18 Aug. 2021. Burkina Faso | UNDP Climate Change Adaptation. https://www.adaptation-undp.org/explore/western-africa/burkina-faso. Accessed 18 Aug. 2021. “Republics of the Soviet Union.” Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, https://www.loc.gov/resource/g7001f.ct001610/. Accessed 18 Aug. 2021. “---.” Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, https://www.loc.gov/item/2005626536/. Accessed 18 Aug. 2021. The Languages of the Soviet Union (Cambridge Language Surveys) by Bernard Comrie: Very Good Paperback (1981) | Fireside Bookshop. https://www.abebooks.com/Languages-Soviet-Union-Cambridge-Language-Surveys/30368345240/bd. Accessed 18 Aug. 2021. Tolmazin, David. “Trends in the USSR Water Resources Development Policies.” GeoJournal, vol. 17, no. 3, Springer, 1988, pp. 389–400. Tyner, James A. “‘Defend the Ghetto’: Space and the Urban Politics of the Black Panther Party.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 96, no. 1, [Association of American Geographers, Taylor & Francis, Ltd.], 2006, pp. 105–18. Your Guide to the World :: Nations Online Project. https://www.nationsonline.org/index.html. Accessed 18 Aug. 2021. AuthorElla Kotsen is an undergraduate student at Bryn Mawr College. She is majoring in English and double minoring in History and Growth & Structure of Cities. She plays Division III women’s basketball and has received Centennial Conference Academic Honors. Her main subject of interest is in geopolitics and understanding the historical implications of colonization in Latin American countries. She is interested in Marxist literary theory and enjoys the work of Fanon, Eagleton, and Althusser. Ella also writes for her own independent blog where she produces opinion pieces, book reviews, and audio-based interviews. Archives August 2021 |

Details

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

About the Midwestern Marx Youth LeagueThe Midwestern Marx Youth League (MMYL) was created to allow comrades in undergraduate or below to publish their work as they continue to develop both writing skills and knowledge of socialist and communist studies. Due to our unexpected popularity on Tik Tok, many young authors have approached us hoping to publish their work. We believe the most productive way to use this platform in a youth inclusive manner would be to form the youth league. This will give our young writers a platform to develop their writing and to discuss theory, history, and campus organizational affairs. The youth league will also be working with the editorial board to ensure theoretical development. If you are interested in joining the youth league please visit the submissions section for more information on how to contact us!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed