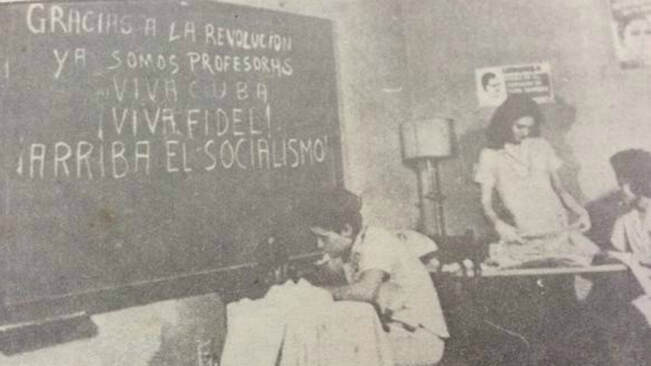

The Status of Women in Pre-Revolutionary Cuba Under the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, which lasted from 1952-1959, women lived under the yoke of a patriarchal society (Lamrani). They made up only 17% of the workforce, often being restricted to the role of mother and domestic caretaker; where they did work, they received much lower compensation than did men (Lamrani). From 1934 (pre-Batista) to 1958, only 26 women held governmental positions in all of Cuba (Lamrani). Women’s Involvement in the Insurrection In 1952, democratically elected president of Cuba, Fulgencio Batista seized total power of the island nation in a coup, suspending the 1940 Constitution, and establishing his rule as a fascist dictator, receiving recognition of legitimacy from the United States government (“Cuba: Timeline of a Revolution). In response to Batista’s dictatorship, many groups with varying ideologies engaged in revolutionary struggle against Batista before Fidel Castro’s 26th of July Movement succeeded in deposing him in 1959 (“Cuba: Timeline of a Revolution”). Among the multitude of anti-Batista groups were two all-women activist groups, the FCMM and the MOU, which were ideologically aligned with the centre-left party and Communist Party of Cuba respectively (Chase). These groups participated in civil protests and press denunciations against the Batista dictatorship, as well as organized support for a hunger strike carried out by political prisoners (Chase). The most significant revolutionary group, though, was Fidel Castro and Che Guevara’s 26th of July Movement, which succeeded in removing Batista from power and establishing Castro as the new leader of Cuba in 1959, after they seized control of Havana (“Cuba: Timeline of a Revolution”). The role of women within the 26th of July Movement was mostly (but not entirely) involved in underground support, which included strategizing, transmitting messages, providing safe houses, and transporting materials (Seidman). This was not their only role, though: Fidel Castro describes the revolutionary involvement of comrade Haydée Santamaría, who was directly involved in the insurrection, the same as were her male comrades: when being interrogated and tortured by Batista’s officers, Santamaría was told that they had killed her brother, to which she replied, “he is not dead; to die for one’s homeland is to live forever” (Castro, 47). Castro remarks on her revolutionary character: “never had the heroism and the dignity of Cuban womanhood reached such heights” (47). Certainly, there was a presence of women in the 26th of July Movement, even if they were outnumbered by their male counterparts (Herman). This can also be seen in the existence of an all-woman squadron within the Movement, called the Mariana Grajales (Lamrani). Women’s active involvement within the revolution, both in their own groups and within the victorious sect, set the stage for their increased role in post-insurrectionary Cuban society. The Feminist Elements and Victories of Revolutionary Cuba In the year following the end of the insurrectionary period of the Cuban Revolution, the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC) was founded by Vilma Espin, who was a revolutionary in the 26th of July Movement and wife of Raúl Castro (Lamrani). The Federation received support from Castro himself, as it sought to end discrimination in Cuba, and defend equality for all (Lamrani). Espin was devoted to the struggle for the emancipation of women and defending the revolution; the FMC’s webpage states: “from the start of the Cuban Revolution, the Cuban leadership has made concerted efforts to advance the status of women and increase their social and political participation, particularly through increased access to educational opportunities and employment” (The Federation of Cuban Women). One of the first objectives of the new Cuban government under Fidel Castro was the Cuban Literacy Campaign, a decidedly feminist policy which sought to eradicate illiteracy from the country (Herman). Castro announced his intention to make the population fully literate in 1960, less than one year into his leadership; illiteracy in Cuba at the time was at about 23.6% (Herman). The Literacy Campaign was carried out by volunteers, 55% of which were women, who taught children, adults, and the elderly students, who were 52% women, how to read and write (Herman). In 1961, just after the end of the year-long campaign, UNESCO declared Cuba to be the first territory free of illiteracy (Lamrani). Greater political actions for the protection of women were solidified by the new Cuban Constitution and the penal code, which created and protected equality rights for women, as well as gave them access to all public offices and joining the armed forces (Lamrani). Article 44 of the updated Cuban Constitution (1976) states: “the state guarantees women the same opportunities and possibilities as men in order to achieve women’s full participation in the development of the country” (The Federation of Cuban Women). In 1975, Cuba passed the Family Code, which was inspired by similar legislation from East Germany, which officially mandated the equal division of housework and childcare between spouses (Seidman). In a speech, Castro affirmed the Cuban state’s commitment to the goals of feminism: “the National General Assembly of the People of Cuba…condemns the inequality and exploitation of women” (Castro, 83). In 1965, Cuba became the first nation in Latin America to legalize abortion on request, making it the second nation ever to do so after the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in 1955 (Lamrani). Abortion was fully legalized in Cuba on four conditions which sought to protect women in the event; abortions had to be the women’s own choice, take place in a hospital, be carried out by trained professionals, and be completely free (Gonzalez). In 1989, Cuba’s National Center for Sex Education (CENESEX) was founded and led by the daughter of Raúl Castro and Vilma Espin, Mariela Castro (Hutchison). Cuba’s improvement regarding its treatment of queer people (as seen in the founding of CENESEX) is distinctly feminist because it contributes to a dissolving of gender-enforced boundaries in society. This feminist progression can also be seen in the fact that gender affirming surgery for trans people is completely free under the nation’s universal healthcare system (Hutchison). When feminist thinker Margaret Randall was forced to flee Mexico due to her involvement in the Mexican student movement, she found refuge in Cuba (Hutchison). Randall noted across her extensive writings that Cuban women used art such as theatre, poetry, music, and literature to challenge continuing sexist notions within the country’s society (Hutchison). Cuba was heavily involved in the movement to free Marxist feminist thinker and political activist Angela Y. Davis while she was being tried for a murder she did not commit in the 1970s, with Cuban officials and the FMC speaking out for her emancipation (Seidman). Both before and after her trial and subsequent acquittal, Davis visited Cuba many times, each time being celebrated for her ideology and identity as a Black Communist Woman (Seidman). She frequently had meetings with Cuban officials on her visits, during which she gave them advice and feedback on the status of women in their country; she once remarked: “the example of Cuba has confirmed that there cannot be a true emancipation for women without a socialist revolution” (Seidman). A similar sentiment to Davis’s idea that women’s emancipation and socialism must be founded together can be found in many speeches and writings by Castro himself: When discussions are held about the rights of women, of their aspirations, we see that there cannot be rights of women in our America or rights of children, mothers, or wives if there is no revolution. The fact is that in the world in which the American woman lives, the woman must necessarily be revolutionary. Why must she be revolutionary? Because woman, who constitutes an essential part of every people is, in the first place, exploited as a worker and discriminated against as a woman. (“Fidel Castro’s Speech at the Closing of the Congress of Women of the Americas”) Castro speaks to the idea that women can only begin to escape the twofold exploitation they face from capitalism and society through revolutionary socialism. The goal of the Cuban Revolution was not only to oust Fulgencio Batista as dictator of Cuba, but also to establish a socialist society built upon the ideals of Marxism, feminism, anti-imperialism, and equality. Castro remarked in a 1963 speech that the socialist elements of the new Cuba were visible in the changing identity of womanhood: “the bourgeois concept of womanhood is disappearing in our country. The concepts of stigma, concepts of discrimination, have really been disappearing in our country, and the masses of women have realized this” (“Fidel Castro’s Speech…”). That which was and is Lacking in Revolutionary Cuba Among the many victories for women and the ideology of feminism accomplished in the early years of the revolution and into the later years of its development, there were also areas which were lacking within the nation. Perhaps at the forefront, and an element which hindered further development for feminism was the assertion by Fidel Castro that Cuba had become a land totally free of gendered discrimination: “in our country, the woman, like the Negro, is no longer discriminated against” (Fidel Castro’s Speech…). Such a reductionist and provably false statement by the country’s leader was harmful in that it spread the untrue notion that sexism was an issue of the past in Cuba, which no longer needed to be dealt with, thus stalling further feminist progression. Similarly, the Federation of Cuban Women was centrally focused on fighting the discrimination against women which is inherent to the capitalist system, and generally did not acknowledge the distinct discrimination against women which existed in Cuban society, apart from the socioeconomic system of the nation (Seidman). Both within the FMC and in the broader scope of the Cuban government and people, defending the revolution and combatting US aggression were prioritized over issues regarding women for decades in Cuba (Hutchison). In terms of more concrete issues regarding the status of women in revolutionary Cuba: in the early years of the revolution, the government released a list of jobs which were considered unfit for women, likely because they constituted a threat to the health and safety of the female reproductive system (Hutchison). This list was reductionist in that it took the view that women should be precluded from working in certain areas of the labour force due to their reproductive abilities, essentializing them to their sex organs. Following the death of Fidel Castro in 2016, the list produced for his potential replacements contained only men, a fact which points to the still existing masculine dominance in the revolution in Cuba (Hutchison). Cuba Today Before an action plan can be provided for improving the future status of women in Cuba, a more modern look at the nation of Cuba must be offered so as to better understand the contemporary needs and wants of the Cuban women generally. Cuba’s Labour Code provides women the right to full salaries while taking a month and a half off before delivery of a child, and three months off after childbirth; this leave may be extended to a full year with compensation equivalent to 60% of regular earnings (Lamrani). Cuban women make up the majority of union leaders, and are required by law to be compensated equally to men (Lamrani). Also in the field of labour, Cuban women make up only 44% of the national workforce, a figure which illustrates the need for further institutional equality and job programs (Lamrani). In the areas of health and education, Cuban women make up 60% of the country’s students and 65% of its graduates (Lamrani). In 1960, just after Castro came to power, the life expectancy for Cuban women was 65.62 years; by 2019, it had risen to 80.78 (The World Bank). Comparatively, the life expectancy for women in the US in 1960 was 73.1 years, more than 7 years greater than Cuba. However, for women in the US in 2019, life expectancy is less than one year greater than that of Cuban women, at 81.4 years (The World Bank). Women still are entitled to free abortion on request (Gonzalez), and to free gender affirming surgery (Hutchison). In the political arena, Cuba ranks second out of every nation worldwide for most women elected to their national parliament, only after Rwanda (Archive of Statistical Data). Cuba has a single house national assembly, in which 322 of the 605 seats were represented by women in February 2019, making up 53.2% of the house (Archive of Statistical Data). As of October 1, 2021, female representation in the Cuban National Assembly of the People’s Power was increased to 53.4% (IPU Parline). It also should be mentioned again that, though women make up majority of the elected Cuban assembly, no women’s names were present on the shortlist to replace Fidel Castro as First Secretary after his death in 2016 (Hutchison). Policies for the Betterment of Cuban Women Women’s involvement in the labour force in Cuba remains an issue, with one 2020 study estimating that just 38.44% of Cuban women work; although this is a much greater number than was the case in as recent as the 1990s, there remains work to be done (Trading Economics). This is an issue which could potentially be solved by the introduction of a guaranteed jobs program in Cuba, something which existed in the earlier years of the revolution, but which was abandoned later on; by guaranteeing work for all Cuban citizens, women would more easily find representation in the national workforce (New York Times News Service). Other issues which may arise against the progression of Cuban women should be combatted by the FMC, an organization and community of revolutionary women. This, however, would be difficult unless the FMC begins to acknowledge sexism as present in Cuban society, rather than just within the context of global capitalism (Seidman). The Federation of Cuban Women should reform itself to recognize discrimination against women as present in all areas of life. Politically, women in Cuba have found full involvement in the National Assembly and in other government organizations such as the FMC, but, as previously mentioned, no women were considered for replacing Fidel Castro as First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba following his death in 2016 (Hutchison). This fact points out the need for women’s continued involvement in the revolutionary process, which can be accomplished by celebrating the feminist victories and acknowledging the failures of the ongoing revolution. It can also be directly achieved by adding politically exceptional women to the potential replacements for the position of First Secretary once Raúl Castro dies. Long Live the Revolution The most critical component for continuing feminism on the island nation of Cuba is the continuation of the revolution. Socialism in Cuba ousted a great deal of the capitalistic oppressions which existed there. Just the same, the revolution eliminated much of the discrimination faced by women thereto. The socialist ideology of the Cuban government and people is a necessary force for both maintaining the currently existing feminism in Cuba, and for improving the status of women in Cuba in the future. In order for women’s lives in Cuba to better, the revolution must be defended. Michael Parenti describes the manner in which rights for women were near abolished after the fall of socialism in the Soviet Bloc: The overthrow of communism has brought a sharp increase in gender inequality. The new constitution adopted in Russia eliminates provisions that guaranteed women the right to paid maternity leave, job security during pregnancy, prenatal care, and affordable day-care centres. Without the former communist stipulation that women get at least one third of the seats in any legislature, female political representation has dropped to as low as 5 percent in some countries. In all communist countries about 90 percent of women had jobs in what was a full-employment economy. Today, women compose over two-thirds of the unemployed. (114-5) Parenti’s analysis of the fall of the status of women in tandem with the fall of Soviet socialism is a warning to Cuba; socialism exists in parallel with women’s rights, and the elimination of one implies the death of the other. There should also be a point made here as to the alternative option to socialism, which is only capitalism: there is either capitalism or socialism/communism. No third ideology can be created, and thus, no liberation for women can be accomplished elsewhere than socialism. “Since there can be no talk of an independent ideology being developed by the masses of the workers in the process of their movement the choice is: either bourgeois or socialist ideology. There is no middle course” (Lenin, 82). The Cuban Revolution was a force which brought about massive social, economic, and political progression for the status of women, and only by consolidating that revolution in future generations can those victories be maintained and progressed. Works Cited Archive of Statistical Data. "Women in National Parliaments." 1 February 2019. archive.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm Castro, Fidel. The Declarations of Havana. 2008. Verso Books, 2018. Chase, Michelle. "Women's Organisations and the Politics of Gender in Cuba's Urban Insurrection (1952-1958)." Journal of the Society for Latin American Studies, vol. 29, no. 4, 2010: 440-458. “Cuba: Timeline of a Revolution.” Aljazeera News, 2009. aljazeera.com/news/2009/7/26/cuba-timeline-of-a-revolution The Federation of Cuban Women. “Women and the Cuban Revolution: The Federation of Cuban Women.” cubaplatform.org/federation-cuban-women “Fidel Castro’s Speech at the Closing of the Congress of Women of the Americas (1963).” marxists.org/history/cuba/archive/castro/1963/01/16.htm Gonzalez, Ivet. "Abortion Rights in Cuba Face New Challenges." Havana Times, 2017. havanatimes.org/features/abortion-rights-in-cuba-face-new-challenges/ Herman, Rebecca. "An Army of Educators: Gender, Revolution, and the Cuban Literacy Campaign of 1961." Gender and History, vol. 24, no. 1, 2012, 93-111. Hutchison, Elizabeth Quay. "Women, Gender, and Sexuality in the Cuban Revolution." Radical History Review, 2020, 185-197. IPU Parline. "Monthly Ranking of Women in National Parliaments." November 2021. data.ipu.org/women-ranking?month=10&year=2021 Lamrani, Salim. "Women in Cuba: The Emancipatory Revolution." The International Journal of Cuban Studies, vol. 8, no. 1, 2016, 109-116. Lenin, Vladimir I. “What Is To Be Done?” Essential Works of Lenin, edited by Henry M Christman, Dover Publications, 1987. New York Times News Service. "In Radical Move, Cuba Ends Guaranteed Jobs." Chicago Tribune, 1995. chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1995-05-14-9505140359-story.html Parenti, Michael. Blackshirts and Reds: Rational Fascism and the Overthrow of Communism, City Lights Books, 1997. Seidman, Sarah J. "Angela Davis in Cuba as Symbol and Subject." Radical History Review, 2020, 11-35. Trading Economics. "Cuba - Labour Force, Female." Trading Economics, 2020. tradingeconomics.com/cuba/labor-force-female-percent-of-total-labor-force-wb-data.html The World Bank. "Life Expectancy at Birth, Female (Years)" The World Bank, 2019. data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.FE.IN?locations=CU Author Nolan Long is a Canadian undergraduate student in political studies, with a specific interest in Marxist political theory and history. Archives December 2021

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

About the Midwestern Marx Youth LeagueThe Midwestern Marx Youth League (MMYL) was created to allow comrades in undergraduate or below to publish their work as they continue to develop both writing skills and knowledge of socialist and communist studies. Due to our unexpected popularity on Tik Tok, many young authors have approached us hoping to publish their work. We believe the most productive way to use this platform in a youth inclusive manner would be to form the youth league. This will give our young writers a platform to develop their writing and to discuss theory, history, and campus organizational affairs. The youth league will also be working with the editorial board to ensure theoretical development. If you are interested in joining the youth league please visit the submissions section for more information on how to contact us!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed