|

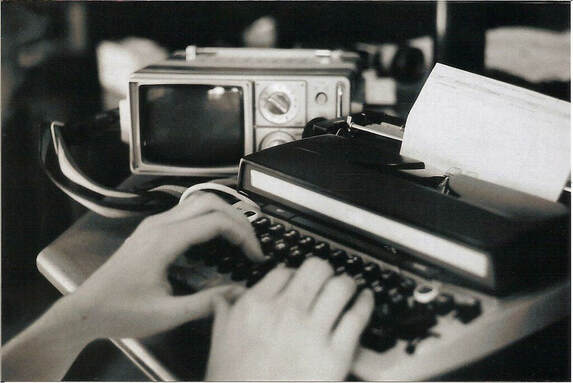

6/24/2021 The Crest of the High Wave: Radical Students and the Underground Press at UNI. By: Ty KralRead Now“History is hard to know, because of all the hired bullshit, but even without being sure of “history” it seems entirely reasonable to think that every now and then the energy of a whole generation comes to a head in a long fine flash, for reasons that nobody really understands at the time—and which never explain, in retrospect, what actually happened...You could strike sparks anywhere. There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning. . . And that, I think, was the handle—that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil. Not in any mean or military sense; we didn’t need that. Our energy would simply prevail. There was no point in fighting—on our side or theirs. We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave. . . So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark—that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.” The story of UNI’s underground press and its student staff stands as a microcosm of the burgeoning political and social changes seen in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. At the University of Northern Iowa, small-town Iowa students and working-class youth became the messengers of the era’s radical politics and student action. At the national level, the United States of the 1960s and early-1970s was a time of massive social upheaval marked by the conflict in Vietnam, social/political movements, and the rise of the “freaks” and the New-Left. We have no shortage of books seeking to explain why so many American youths grew restless and dissatisfied with their country, and why so many turned to left-wing politics throughout the decade. Whether they’re viewed through a liberal, conservative, or socialist lens, the Sixties (the all encompassed decade) is a topic that is still fiercely debated today. Depending on the researcher or daytime television wonk, the Sixties stands as a watershed moment in American culture. But the counterculture of these youth rebels and “freaks” is most often attributed to the coastal cities and major universities in the USA. Areas such as the Midwest are often forgotten about or brushed aside by the more “exciting” locations such as San Francisco and Berkeley. So, it is my goal with this article to nullify those notions and discuss the radicalism that was present at UNI. The counterculture of the Sixties was a diverse and expansive list of comedy, music, drugs, and writing. One facet of this massive ocean of movements was the rise of the so-called underground press in cities such as New York and San Francisco, especially at the universities. For those on the New-Left, underground newspapers were the alternative to the dismissive critiques of the mainstream media and provided their readership with a vulgar, passionate look into the cultures in which they lived. In 1965, the New Left could only claim 5 such newspapers, mostly in big cities, but within a few years, several hundred newspapers were in circulation with a combined readership in the millions.[1] Underground newspapers, according to Abbie Hoffman, were the “... most important institution in our lives... It keeps tuned in on what's going on in the community and around the world. Values, myths, symbols, and all the trappings of our culture are determined to a large extent by the underground press.”[2] The story of the underground press at the University of Northern Iowa begins with a newspaper called the Campus Underground in 1968. The Campus Underground was conceived by a publisher named Doug Warrington who aspired to make it a nationally syndicated newspaper. Its office was located 401-⅓ Main Street, Cedar Falls, Iowa, presently the location of the Voodoo Club Bar. In the beginning, the paper had 30 representatives from colleges and universities across the state who contributed articles and tips. The paper’s editor, Bruce “Bruno” Niceswanger, was a master’s student at UNI who was recruited by Doug Warrington after a search at all three state universities in Iowa.[3] The first issue was released on October 21, 1968, In this issue, they discussed segregation at Loras College, draft board protests across the state, and a feature-length editorial from David Quegg on his experiences among the protesting and riots at the Chicago DNC Convention of 1968 that previous summer. But after a few issues, a lack of resources and communication led to less participation from other campuses, and Cedar Falls became its primary audience.[4] While not a major success on campus, the paper gained a dedicated following as it grew more progressive and bolder with each issue. That was until the late fall of 1968, in which a review of Norman Mailer’s “Fall of Miami and the Siege of Chicago” by Carl Childress, a controversial UNI English professor, used a quote that contained a certain four-letter word. After this, the local printers refused to print any further issues unless the obscenity was removed, especially as the pressure of printing an underground newspaper grew.[5] The staff of Campus Underground was then forced to build their own light tables and lay out the paper themselves. After this, the paper began to face financial woes as the costs were just barely met from each issue to the next. By the spring of 1969, the staff began to print notices informing the readers about their financial situation while asking for donations.[6] According to a 1971 article from the Northern Iowan, at one point the staff was short $100 of the printer’s fee and frantically rushed around the Hub looking for donations until they finally received the necessary funds.[7] The last Campus Underground came out on March 10, 1969, due to a combination of financial problems, student disinterest in politics, and everyone going home for the summer. But this was far from the end of the underground presses run at UNI. The summer of 1969 saw Woodstock and the birth of Abbie Hoffman’s “Woodstock Nation”. This saw the blossoming of the cliché Sixties counterculture that we know today. By that fall, scores of “freaks”, or hippies, began to arrive at UNI, and with them came the rise of more radical elements such as members of the New Left. With this new wave came the arrival of the rebranded Campus Underground, now named the New Prairie Primer. Edited again by Bruno Niceswanger, the paper was assisted by the dedicated core group of Dave Quegg, Peg Wherry, Jean Seeland, and Gary Hoff. The New Prairie Primer, which I’ll refer to as the Primer from here on out, served as the epitome of this new spirit on campus. The first volume of the Primer Released on October 4, 1969, with a several page long expose by Bruno on his and David Quegg’s experiences at Woodstock titled “Going Up to Meat County.” This article proved to be very popular among UNI students, and it helped set the mood for future iterations of the paper with its quick wit, vulgarity and Hunter S. Thompson style prose and reporting. Following the success of their first issue, the Primer had received enough donations to print thousands of copies for their second edition, a free issue about the Vietnam War to coincide with the events of the STOP Vietnam War Moratorium across the state.[8] This issue contained stories from draft dodgers across the state, including a UNI student named Dick Simpson who explained why he refused induction into the armed services. It was also the first publication anywhere in Iowa to list all the state’s war dead.[9] This issue also showed a great deal of cooperation among various statewide church ministries with the radical left and anti-war hippies in the anti-war movement. But this seemingly unlikely coalition produced results unlike that seen anywhere else in Cedar Falls. The previous 1968 moratorium had brought out only 300 marchers, but by the moratorium on October 15, 1969, nearly 2,000 marchers flooded the UNI campus.[10] But this relationship also drew some ire from the community at large, especially as the Primer’s office was in the Bethany House on College Hill, where the Primer had special arrangements with the United Christian Ministry to use their property.[11] One chief critic of this relationship was a cantankerous, editor of the Waterloo Daily Courier named Bill Severin, also known as the Iron Duke. On the front page of the October 12th issue, the Iron Duke stated, “I have no quarrel with Niceswanger, Quegg, et all, or their right to publish a radical leftwing newspaper. But they and the United Christian Ministry would seem to make strange bedfellows.”[12] In response, the Primer blew the incident out of proportion with a smug, tongue-in-cheek center spread titled, “Primer Staff Bewildered, Hurt”, featuring their high school pictures and squeaky clean, cliché records as small-town Iowan youth along with their own reactions to the Iron Duke’s accusations.[13] This incident was a boon to the Primer’s sales and cemented the Primer’s tone for the rest of the year as a humorous, yet informative publication on campus counterculture. The Primer’s first run was an array of everything from local music reviews and interviews with Waterloo civil rights activists. Having shifted their focus from national news in the Campus Underground to local coverage, the contents of the Primer give an interesting look into the culture of the Cedar Valley during this time. Of course, one of the most important issues on campus at the time was that of drugs. The Primer featured tongue in cheek critiques of the local CFPD “Narcs” and the pearl-clutching of the more conservative Cedar Falls residents. In one such issue the Primer covered a community symposium on the issue of recreational drug use in the Cedar Valley. In response to the symposium, the Primer printed tutorials on how to make your own joints and listed the local street prices of dope, hash, and LSD at the time.[14] One informative, and fascinating article from this period was an interview conducted by the Primer’s own Bruno Nicewanger and their secretary Marsha Petersen titled “3 Viet Vets Rap on the War”.[15] Released with the fourth issue in November 1969, the Primer spoke with three UNI students that had served in Vietnam about why they became involved with the anti-war movement after their time overseas. In retrospect, what made this article fascinating is that the interviewees represent what I deem to be a decent overall representation of Iowan’s backgrounds at the time. Tony Ogden was a 24-year-old white male from Sanborn, Iowa, a town in Northwestern, Iowa. Dave Sessions was a 28-year-old white male from the medium-sized industrial town of Mason City, Iowa. Sam Dell was a 22-year-old African American male who was born in Phillip, Mississippi, but had grown up in Waterloo, in eastern Iowa. While not a full cross section of Iowa’s socioeconomic makeup, these three men represent facets of Iowa’s urban and rural population who converged on Iowa’s campuses during this period of cultural and political turmoil. In summary, all three guys described their experiences overseas, their backgrounds, and their journey towards realizing the atrocities and injustices happening in Vietnam. Tony described the brutality he saw unleashed upon the Vietnamese people he came close to, Sam talked of the racism that followed the military overseas, and Sessions spoke of the bureaucratic apathy towards the death and destruction being perpetuated by armed forces. As such, each man's experiences caused them to question their values and ideological frameworks, driving them towards becoming radically against a system they saw as needlessly unjust and cruel. A passage that stood out when reading this interview was from its final page, which saw all three men ruminating on the meaning of the “American tradition” and the contradictions they saw during their service. As Tony put it, “Seeing marines kneeling within sight of a pile of bodies having a chaplain cram wafers down their throats, under a cross.” While there are plenty of sections one could discuss from these interviews in the Primer, I see this insight into these three young men as a poignant look into the mindset of the emerging student radicals in the United States. But I have also not yet been so clear as what constitutes a student radical currently. And in sincerest sense I have struggled to find a definition insofar as who “they” were. In 2019, even as much then, the term “student radical” has many different connotations depending on who you ask. For the most part, a “student radical” is usually considered to be someone who holds left wing values and belongs to various flavors along the left-wing spectrum. To the politically illiterate, this would mean anyone to the left of the center right or is a “liberal”, but I digress. While a whole paper can be made on the distinction, a radical can be most definitely defined as an individual who opposes the status-quo and calls for a new system of governance and the distribution of resources. In the era of the Primer, as Vietnam raged and COINTELPRO lurked in the shadows, “student radicals” were a hodge podge of nondenominational leftists, middle-class liberals, and the “flower power” freaks. Much like discourse in the vague progressive leanings of today, the ‘60s were a ripe era of barraging liberals and infighting amongst different leftist ideological sects. However, for the most part, UNI’s left-wing and liberals found somewhat common ground in the anti-war movement and demands for more succinct student rights on campus. As is, the Primer got an uptick in sales due to the pearl-clutching of local Cedar-Loo residents after allying with the United Campus Ministries in October of ‘69. And as further articles prove within the Primer, Cedar-Loo was not that far off from the rest of the United States. Labor disputes, gentrification, environmental pollution, and racial tensions were proliferating in Waterloo. Like Joker's duality of man in Full Metal Jacket, Waterloo, Iowa, has had a tumultuous history with segregation. In the fall of 1968 these issues, and industry layoffs, led to instances of rioting in select areas of Waterloo.[16] Other concerns at the time included pollution being released by the John Deere Company and Chamberlain Manufacturing Co. that was potentially contaminating the Cedar River. The Primer then served as a repository, or even a messenger, of these causes that were not often covered by the mainstream media in the community. In a special issue about ecology, the Primer advertised events from an environmental group called SOMETHING, deriding the local tv station for passing environmental pollution onto the individuals during a special sponsored by John Deere and Chamberlain Co.[17] The Primer also teamed up with the Grinnell based-paper the High and Mighty to co-author the so-titled “Military-Industrial Complex” and Iowa’s role in the US war machine, in which they listed the major Iowa companies with defense contracts, including the amount of the contract and what products they produced for the military. Chamberlain Co. of Waterloo was a company that was directly targeted by the Primer due to their production of ammunition for the war movement. But of course, the Primer did not neglect campus issues, especially as they covered the Spring 1970 student government elections in which the Primer backed Students Rights Party participated. However, after suffering a defeat, the Primer declared a so-called “revolutionary student government” on campus which was coordinated by UNI students Al Woods, Sam Dell, and Tony Ogden.[18] By this time, Bruno stepped down as editor to form a collective editorship with everyone on the staff, in which the Primer did its part to become a forum for those who wanted to organize on campus. Among other issues, the Primer waged an aggressive campaign against the Dean Voldseth, Dean of Students, in the leadup to the potential referendum of 1970. The Primer, for several issues, was inscribed with the back-page message of “Dean Voldseth is alive and well in Cedar Falls--Still.” This campaign fizzled out once the student senate was unable to override Student President Mike Conlee’s veto against the referendum. However, that following spring UNI would face one of the largest events to happen on the campus during its history, the UNI 7. Throughout 1969 and 1970, the Afro-American Society, led by UNI students Palmer Byrd and Sam Dell, had been working with the administration at UNI to establish a minority culture house on campus. The process, however, was arduous and the prospect of minority students having their own cultural house drew flak from administrators and parents of students alike. So, in March 1970, 10 African-American students at UNI visited President Maucker’s home late at night to have a discussion with him to take more concrete action on the request for a minority culture house before the board of regents. However, the discussion became visibly heated as the hours went on and President Maucker repeated that he would not sign a document for a specific house and demanded that they leave. The students refused and Maucker returned with his wife to bed while a night guard sat with the youth in the living room as they decided to sit still until some action was taken. By the next morning, rumors began to fly around campus and students began to clamor around the President’s House to view the commotion. By then the sit-in had grown to 40 individuals as radical elements and sympathetic liberals showed their support to the Afro-American students against the slowness of “the system”[19] But after a few more hours, the arrival of the press, and an incoming injunction, the sit-in students elected to move to an administrative building to continue their sit-in, but decided to end the sit-in with no press release which might rile up the administration and media. By the end of the week, Dean Eddie Voldseth announced that seven students were to be suspended pending an investigation by the student conduct board. By the March 31, 1970 issue, the Primer had begun to cover the case and the subsequent student hearings. The staff also worked with other students to storm the hearings and helped solidify a growing campus movement that fed off the growing student dissatisfaction of the administration with the 7.[20] Then with the coming of the invasion of Cambodia and the Kent State killings, the campus grew more divided as there were those who wanted to act and those who did not. But by then another summer was on the way and most students at UNI had packed up to go home. That summer was predicted to be the summer of “Ohio”, or the summer in which the radicals and progressives alike take extreme action in honor of the dead at Kent State. However, this prediction never came to pass. Once students returned to UNI in in the fall of 1970, the political fervor and calls for radical change had seemingly disappeared overnight. While the Primer did return that fall, almost all the papers veterans and staff had either graduated or lost interest. The paper was then edited collectively by John O’Connor, Dick Faust, Bill Yates, and Diana Morgan with a shifting focus away from the “freak” audience that had been its base. John O’Connor thought that while the counterculture and drugs had been useful in radicalizing people, it was coming to the point where it was becoming counterproductive. O’Connor instead sought to change the Primer from being an entertaining, informative magazine for the counterculture to being like that of a classical, educational journal that sought to discuss theory and ideology. In O’Connor’s own words, “We’d like to think people would rather read about a problem and make up their own minds than go to a Speak-Out and find out what happens to be in the wind that day. It is unfortunate that people around here seem to think they need a leader for solutions. They should come to their own conclusions. But this is not to say that they shouldn’t unite, once those conclusions have been reached. We hope that the articles we’re printing now will help people to become better informed, so that the eventual decisions reached will be the right ones.”[21] In this stripped down format the Primer hoped that by losing the “freak” edge they would be better able to reach liberals and workers alike. But this third edition of the New Prairie Primer lasted for only 8 issues from June of 1970 to December of 1970. The Primer finally floundered in December 1970 after a lack of money prevented them from printing any more issues. Considered the longest running underground paper in the history of the state of Iowa, the New Prairie Primer had only lasted for two-and-a-half years. As such, the New Prairie Primer was the first and last of its kind on the campus of the University of Northern Iowa. While this wouldn’t spell the end of student action on campus, far from it, the end of the Primer marked the end of a short but explosive era of student politicization at the University of Northern Iowa. Dozens of committed students and volunteers spent countless hours working to create the Primer in their dorms and in the streets. But one thing is clear, we will never again see anything like the underground press of the Sixties. The technology that spawned the underground press is practically obsolete and it is simply no longer exciting or cost-efficient to transfer inked images to paper. And as John McMilian says in his book “Smoking Typewriters”, “...The movement that fueled the growth of underground newspapers is likewise extinct. Of course, the Sixties remain а force in American popular culture; so momentous were that decade's events that even subsequent generations have come of age in its afterglow. But the underground press had а specific raison d'erre: it was created to bring tidings of the youth rebellion to cities and campuses across America and to help build а mass movement. And for all its shortcomings -- intellectual, and even sometimes moral-- this is something it did remarkably well.”[22] Whether they advanced the hard-nosed analysis of SDS and its offshoots, or the likes of Huey Newton and Noam Chomsky, or championed the new liberated lifestyles seen with the Woodstock Summer, radical newspapers became the medium through which the youth transmitted their arguments and ideas to try and popularize their rebellions. And because of the underground newspapers’ extraordinary inclusiveness, they helped frame the decentralized operations and diverse social relation within the New Left. But as we saw with the Primer, this did not come easily. For many papers like the Primer, their staff were often deluged with bills they couldn’t pay, lack of time, and coordinating a group made producing an underground paper a nightmare. But this didn’t discourage thousands of youth radicals to create their own papers across the United States. After reading something like the Primer, one can see it was a finished product of love-labor that tried to communicate with kindred minds and maybe had converted a few minds along the way. The Primer’s demise is but a small example of this short, yet manic era in American history. As the Sixties ended and gave rise to the Seventies, the passionate campaigns of American radicals and their youth following had seemed to fall on deaf ears. Vietnam still lumbered on in the background for five years, Nixon and Kissinger performed their own dirty backroom deals, the enthusiasm on the campuses seemed to wane. Thus, we had entered the era of Taxi Driver and Deep Throat, the forces of evil had seemingly won as the far-right gathered momentum and prepared for the launch of Reagan and Bush less than a decade later. But the democratic sensibilities that Sixties youth had brought to journalism not only persist, but have also taken on a life of their own. And they are still likely to endure in some fashion or another. For radicals today, the internet holds tremendous promise and opportunity with the rise of online forums, social media, and internet podcasts. But much of what the 2000s blogosphere and left-wing YouTube, referred to as “BreadTube,” have accomplished today with building communities and democratizing the media was accomplished more than 40 years ago by the frank, vulgar, and threadbare papers of the underground press. While there may be little evidence left of the Primer’s impact on the University of Northern Iowa, the culture of student activism hasn’t completely died out. While it lies mostly nascent, the vigor and passion of the 1960s still emerges for a moment every decade or so. Whether that be the Iraq War protests of the 2000s or the Racial and Ethnic Coalition of 2019, and statewide campaigns by Iowa Student Action. In conclusion, the story of UNI’s underground press and its student staff stands as an example of the burgeoning political and social changes seen in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. At UNI, small-town Iowa students and working-class youth became the messengers of radical politics and student action during their time. The culture the Primer spread to the masses persists today with the new generation of radicalized youth. Notes [1] McMillian, James. Smoking Typewriters (New York; Oxford University Press, 2011), 4. [2] Hoffman, Abbie. Steal This Book (Pirate Editions, Grove Press, 1971), 92. [3] Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 1.” Northern Iowan, February 12, 1971. [4] Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 1.” Northern Iowan, February 12, 1971 [5] Niceswanger, Bruno. “Editor’s Note.” New Prairie Primer, December 9, 1968. [6] Niceswanger, Bruno. “Editor’s Note.” New Prairie Primer, January 27, 1969. [7] Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 1.” Northern Iowan, February 12, 1971 [8] Quegg, David. “In This Issue.” New Prairie Primer, October 4, 1969. [9] Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 1.” Northern Iowan, February 12, 1971 [10] “Scenes from the Revolution: Iowa #1.” New Prairie Primer, October 25, 1969. [11] Wherry, Peg. “Underground Newspaper In Circulation Under New Name.” Northern Iowan, October 7, 1969. [12] Severin, Bill. “Bill Severin, the Iron Duke.” Waterloo Daily Courier, October 12, 1969. [13] Bruno Niceswanger, et all. “Duke Blasts Bedfellows!!!” New Prairie Primer, October 25, 1969. [14] “Primer Special Drug Supplement.” New Prairie Primer, March 3, 1970. [15] Bruno Niceswanger, et all. “3 Viet Vets Rap on the War.” New Prairie Primer, November 13, 1969. [16] Nelson, Thomas. “This week marks 50 years since the 1968 riot in Waterloo. We look back.” The Courier, September 9, 2018. [17] “.” New Prairie Primer, April 27, 1970. [18] “Revolutionary Student Government Declared.” New Prairie Primer, March 31, 1970. [19] Ogden, Tony. “UNI 7.” New Prairie Primer, March 31, 1970. [20] Niceswanger, Bruno. “The UNI Struggle: What It Means.” New Prairie Primer, April 27, 1970. [21] Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 3.” Northern Iowan, February 19, 1971 [22] McMillian, James. Smoking Typewriters (New York; Oxford University Press, 2011), 188. Bibliography Hoffman, Abbie. Steal This Book (Pirate Editions, Grove Press, 1971) McMillian, James. Smoking Typewriters (New York; Oxford University Press, 2011) Nelson, Thomas. “This Week Marks 50 Years since the 1968 Riot in Waterloo. We Look Back.” The Courier. September 9, 2018. https://wcfcourier.com/news/local/this-week-marks-years-since-the-riot-in-waterloo-we/article_761a2ea4-3bdb-5ea9-89f7-e90172d41a82.html. Niceswanger, Bruno, et all. “3 Viet Vets Rap on the War.” New Prairie Primer, November 13, 1969. Niceswanger, Bruno, et all. “Duke Blasts Bedfellows!!!” New Prairie Primer, October 25, 1969. Niceswanger, Bruno. “Editor’s Note.” New Prairie Primer, December 9, 1968. Niceswanger, Bruno. “Editor’s Note.” New Prairie Primer, January 27, 1969. Niceswanger, Bruno. “The UNI Struggle: What It Means.” New Prairie Primer, April 27, 1970. Ogden, Tony. “UNI 7.” New Prairie Primer, March 31, 1970. Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 1.” Northern Iowan, February 12, 1971. Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 2.” Northern Iowan, February 15, 1971. Pedersen, Steve. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Primer Pt. 3.” Northern Iowan, February 19, 1971. Quegg, David. “In This Issue.” New Prairie Primer, October 4, 1969. Severin, Bill. “Bill Severin, the Iron Duke.” Waterloo Daily Courier, October 12, 1969. Shackelford, Christopher J., "A Midwestern culture of civility: Student activism at the University of Northern Iowa during the Maucker years (1967-1970)" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 29 Wherry, Peg. “Underground Newspaper In Circulation Under New Name.” Northern Iowan, October 7, 1969. “Primer Special Drug Supplement.” New Prairie Primer, March 3, 1970. “Revolutionary Student Government Declared.” New Prairie Primer, March 31, 1970. “Scenes from the Revolution: Iowa #1.” New Prairie Primer, October 25, 1969. “Special Edition on Life” New Prairie Primer, April 27, 1970. AuthorTy Kral is an undergraduate student of History at the University of Northern Iowa, with a primary focus on public history and museum studies. Ty is a socialist obsessed with the study of history and is particularly interested in Marxist thought, Iowa history, and the history of the Soviet Union. He has been a member of the UNI YDSA for over two years. After school, Ty hopes to find work in museums or archives and eventually go to graduate school.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

About the Midwestern Marx Youth LeagueThe Midwestern Marx Youth League (MMYL) was created to allow comrades in undergraduate or below to publish their work as they continue to develop both writing skills and knowledge of socialist and communist studies. Due to our unexpected popularity on Tik Tok, many young authors have approached us hoping to publish their work. We believe the most productive way to use this platform in a youth inclusive manner would be to form the youth league. This will give our young writers a platform to develop their writing and to discuss theory, history, and campus organizational affairs. The youth league will also be working with the editorial board to ensure theoretical development. If you are interested in joining the youth league please visit the submissions section for more information on how to contact us!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed