|

In any capitalist society, a disconnect between an individual’s selfhood and her labor will arise. Ask any college student and you’ll hear about the never-ending questions that go something like… What career do you want with your degree? What field are you looking into? Where do you want to work once you graduate? Inevitably accompanying that question comes intense anxiety for the student themselves. Yet, this isn’t an issue only experienced by college students— questions concerning one’s career never cease to end. They usually present in different forms, most often as self-reflecting questions the working-class subconsciously ask themselves every day… Man, what am I doing with my life? I just have to get to the weekend! I hate my job but my kids need food on the table. According to Che Guevara, capitalism moves people away from expressing their interests without even knowing it.[1] And even beyond alienating people from their interests, the interrelation between a person’s ability to produce, save, and organize[2], which are vital elements of a revolution, are also damaged under capitalistic systems. People are disconnected from their labor because even if they are working in a field they are interested in, capitalism separates the individual from the products of their labor and likewise, disconnects them from their sense of self and purpose. Martizen-Sanez writes, “The distinction that people experience between communal interests and individual interests arose because in capitalist society, human beings lacked the control of the distribution of the products of their labor and were treated as a means to an end rather than an end; their relations were reduced to purely economic relations, and the difference between an animal and a human existence had become unintelligible” (Martinez-Saenz, 24). This alienation under a capitalist system is something Marx and Guevara shared in concern. If the individual is alienated because of oppressive external conditions under capitalism, then the individual will inevitably lose touch with self. So, not only are workers frustrated with the inability to reap the fruits of their labor but they are forcibly stripped of any identity of selfhood. Marx talks of this exact same issue in his manuscript Alienated Labor. Petrović writes of this when considering Marx, stating, “The alienation of the results of man's productive activity is rooted in the alienation of production itself. Man alienates the products of his labor because he alienates his labor activity, because his own activity becomes for him an alien activity, an activity in which he does not affirm but denies himself, an activity which does not free but subjugates him. He is home when he is outside this activity, and he is out when he is in it” (Petrović, 241). Labor becomes alien to the worker who is completely disconnected from their work. Yet perhaps even worse than Marx could have predicted, “home,” where “he is outside this activity” is arguably no longer even a space where his selfhood can be reconnected in the United States. Labor has not only alienated the worker from his work but has created such extreme conditions that almost all spaces are now alienating in this country. Marx and Guevara weren't the only ones to recognize the divide capitalism causes between labor and passion, capital and self. W.E.B. Du Bois, Huey Newton, and Paul Robeson all observed not only the social differences in the Soviet Union and Mao’s People’s Republic of China, particularly related to race, but also the differences in how the working people of these places viewed and digested their labor. While we can obviously recognize the differences in their ability to reap the fruits of their labor compared to US workers (or any workers under capitalism or neoliberalism), less often do we examine the psychological relationship a Marxist revolution enables. The psychological relationship being the connection one has between his labor and his selfhood. Du Bois immediately recognized the safety and welcome he felt when he visited the Soviet Union. Yet, even beyond those social changes, he was also able to observe a new dynamic among the working people. “Du Bois applauded the Soviet program, which had made of the working people of the world ‘a sort of religion,’ a form of scientific idealism he posited as being indispensable to progress” (Carew, 54). The Soviets were dedicatedly connected to their work— producing historically groundbreaking results (we mainly consider the scientific ones), but they also psychologically pushed an entire population onwards with the same unifying intensity exhibited in religion. Du Bois’ idea that work can create a motivating spirit in the people is something he also observed in China: “Du Bois saw ‘a fable of disciplined bees working in revolutionary unison. Cataloging the public places, restaurants, homes of officials, factories, and schools visited,’ he saw only ‘happy people with faith that needs no church or priest’” (Carew, 61). Once again we have this reference to a sense of drive, pride, and motivation so unifying that it is comparable to the togetherness brought on by religion. Workers had faith in their labor and therefore did not struggle with the questions that I examined earlier in this piece. Work in Marxist societies erases the disconnect that laborers otherwise have between their selfhood and work-life in capitalist systems. Huey Newton also observes the connection between selfhood and labor that America lacks when he visited The People’s Republic of China: “While there, I achieved a psychological liberation I had never experienced before. It was not simply that I felt at home in China; the reaction was deeper than that. What I experienced was the sensation of freedom as if a great weight had been lifted from my soul and I was able to be myself, without defense or pretense or the need for explanation. I felt absolutely free for the first time in my life-completely free among my fellow men. This experience of freedom had a profound effect on me, because it confirmed my belief that an oppressed people can be liberated if their leaders persevere in raising their consciousness and in struggling relentlessly against the oppressor… To see a classless society in operation is unforgettable. Here, Marx’s dictum— from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs— is in operation” (Newton, 348, 352). Again, Newton mentions this psychological liberation that is almost spiritual or religious in nature. The societies that America paints as those in which people are forced to work for “hours without reward,” in reality actually provide a sense of freedom and liberation for one's selfhood through Marxist labor structures, the antithesis to everything we’re told in school. Yet it cannot be a coincidence that all of these African-American revolutionaries observed such similar feelings of liberation. Undoubtedly, the widespread feeling of disconnect that I described earlier in America’s working culture, is the exact opposite in cultures that have experienced Marxist revolutions. In places where Marxist revolutions have occurred, a feeling of intense connection to one’s labor arises. Du Bois and Newton do not speak of the mysticality of an un-alienated society randomly. Petrović also accounts for the same role the rejection of alienated labor has in a spiritual setting: “In this sense, Marx… speaks about communism as a society which means ‘the positive supersession of all alienation and the return of man from religion, the family, the state, etc., to his human, i.e., social life (existence)’” (Petrović, 424-425). If alienation between a worker and his work is ended, he will be able to return to his truest human condition and existence. In the same sense that Du Bois and Newton observed, ending alienation in labor, returns the man to his truest self. Paul Robeson, a local hero for my fellow Princeton, New Jersey residents, found this connection so powerful (that along for obvious social reasons) he moved his family to the Soviet Union for a period of time.[3] This reinforces the notion that Marxist revolutions create spaces for marginalized people to not only experience less racial prejudice than in the States, but also a complete liberation of selfhood. A liberation that can remove the constraints of not only racial oppression, but of the realities that all working class people experience in the United States: the inevitable disconnect between selfhood and work, or labor-alienation, that is inevitable in capitalist-based systems. Che Guevara’s idea of the “new man,” is the alternative that American workers need. In America’s capitalist hellscape, not only are adult workers disconnected from the fruits of their labor and individual sense of belonging and purpose, but the youth population is as well. We tell our youth they have to work to survive, but when they produce the tools of their survival they are completely stripped of the fruits themselves. Instead, the products of their labor go to the bourgeoisie so that this system can continue. And not only are people physically disconnected from the products of their labor, but they are psychologically disconnected from their labor as well. This makes it nearly impossible to love or find meaning in one’s job, regardless of one’s theoretical interest. Instead, American workers work only to put food on their families’ “tables” (arguably the vicious cycle doesn’t even allow that). It's a twofold issue that creates a never-ending cycle that is intentionally impossible for the working-class American to escape. Make the working-class person work a job that only gives him enough to keep him in an endless cycle of crises until he no longer love his work and can no longer love himself. Yet if we have a revolution in this country, if our workers are able to embody Guevara’s vision of the “new man,” the connection between laborer and labor can be reformed. Martinez-Saenz quotes Guevara who said, “The relation of economic controls to moral incentives is more subtle than indicated. Moral incentives, if they are truly the individual’s incentives, cannot be directed from above. That is why the many Cubans ask, ‘How can you plan voluntary work? Is this not a contradiction in terms?’ What types of economic controls are compatible with a system of moral incentives? Recognition of this issue has emerged in two forms. First, an understanding that moral incentives are directly related to the level of education and the nature of one’s employment, and this is reflected in Cuba’s intensive educational effort, particularly in technical training. Second, experimentation with a new worker organization and system of emulation whose aim in part is to stimulate greater participation and eliminate bureaucratic controls” (Martinez-Saenz, 22). Guevara clearly lays out these two steps that are important to understand in order to truly alleviate the disease of worker alienation. America, however, is nowhere close to adopting the steps Guevara saw for the people of Cuba: a revolution must take place first. This issue, therefore, is actually deeper than just a singular failure of capitalism. We know that it will be the working-class that unites to create a revolution in this country. Here we see the perfect connection: it is a working-class issue that can only be alleviated by the working-class themselves. It will take a revolution led by the working class to instate a positive relationship between workers and work. The myth of the “American Labor Shortage” shows the dissatisfaction the working class has with the exploitation of their labor. Now, more than ever, the working class must band together to revolutionize a system that does not work for them. To not only create a place where they can reap the fruits of their labor, but where workers can love their work and reject alienation. [1] Martinez-Saenz, Miguel. “Che Guevara’s New Man: Embodying a Communitarian Attitude.” Latin American Perspectives 31, no. 6 (November 1, 2004): 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X04270639. (pg 21). [2] Martizen-Saenz, 21 [3] Carew, Joy Gleason. Blacks, Reds, and Russians: Sojourners in Search of the Soviet Promise. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2008. muse.jhu.edu/book/6044. Work Cited Carew, Joy Gleason. Blacks, Reds, and Russians: Sojourners in Search of the Soviet Promise. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2008. muse.jhu.edu/book/6044. Martinez-Saenz, Miguel. “Che Guevara’s New Man: Embodying a Communitarian Attitude.” Latin American Perspectives 31, no. 6 (November 1, 2004): 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X04270639. Newton, Huey P., and Fredrika Newton. Revolutionary Suicide: Reprint edition. New York: Penguin Classics, 2009. Petrović, Gajo. “Marx’s Theory of Alienation.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 23, no. 3 (1963): 419–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/2105083. AuthorElla Kotsen is an undergraduate student at Bryn Mawr College. She is majoring in English and double minoring in History and Growth & Structure of Cities. She plays Division III women’s basketball and has received Centennial Conference Academic Honors. Her main subject of interest is in geopolitics and understanding the historical implications of colonization in Latin American countries. She is interested in Marxist literary theory and enjoys the work of Fanon, Eagleton, and Althusser. Ella also writes for her own independent blog where she produces opinion pieces, book reviews, and audio-based interviews. Archives December 2021

0 Comments

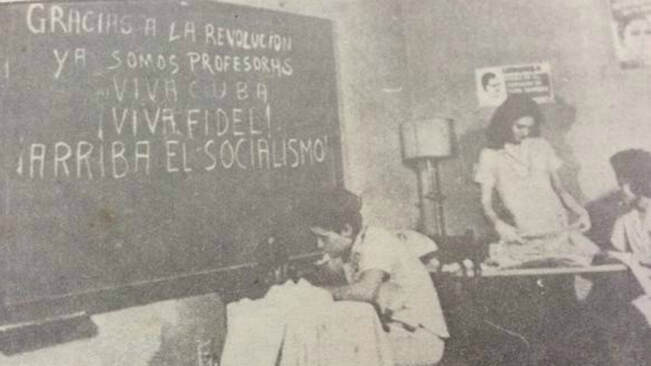

12/13/2021 Letters to a Southerner: Comparing French Peasants to American Southerners via Bakunin’s “Letters to a Frenchman on the Present Crisis”. By: Jae SatolaRead NowAlthough I am not an Anarchist by any means, I could not help but agree with the Father of Russian Anarchism, Mikhail Bakunin, in his 1870 work, “Letters to a Frenchman on the Present Crisis”. In which he outlines his belief that the urban proletariat is not the only vessel for revolution in France. Rather, the peasantry is an essential part of any potential social revolution as well. Although we no longer have a peasantry, comparisons can be drawn between modern non-bourgeois Southerners in the United States and French peasants in the nineteenth century. As Bakunin outlines, Peasants tend to be religious, loyal to the emperor, and intensely patriotic. They are labeled as ignorant and they have an attachment to private property which keeps them from accepting Communism as an ideology. All of which is surprisingly similar to the modern, non-bourgeois Southerners of the United States. According to Bakunin, peasants are religious. They are superstitious “due to their ignorance, [which is] artificially and systematically implemented by all the bourgeoisie governments” (Bakunin). This is not to say that religion as a whole is bad, rather religion inherently supports Marxism. However, religious institutions that are in the hands of the bourgeois government can work against the people and what their doctrines stand for. For example, the numerous megachurches present in the United States. These institutions operate for monetary gain and often push fear-mongering propaganda upon their members. They lock the doors to a holy house of G-d which should be open to the public with barbed wire and security guards. They request tithes from their members, much like indulgences, which insinuate that paying for faith will make one more holy. All the while being exempt from taxes. Think about how the Bible Belt infamously has some of the most conservative populations in the US. Bakunin suggests the solution to this is not to violently abolish religion, as Marx suggested, but to educate the peasants. To take this one step further, it would be best to teach real religion as it is meant to be rather than religion that has been modified by the state to be used as propaganda. Teach the help-thy-neighbor religion, not the burn-in-hell-G-dless-communists religion. After all, religion at its core has doctrines that directly align with the Communist cause. It is simply a matter of taking power away from corrupt religious institutions in collusion with the state. The modern southern proletariat also has an intense love of private property, just as the French peasants had in the 19th century. This “fanatical commitment to the individual ownership of land”, as Bakunin puts it, seems ignorant to the urban Marxist; however, it makes sense. Why would someone who has been able to scrape together a small amount of property so that “he and his loved ones shall not die of hunger and privatization in the economic jungle of this merciless society” not cling to it dearly (Bakunin)? To the southern proletariat, their property is their livelihood; it is all they have and all they are able to use to provide for those they love. Thus, they fear those who advocate for the abolition of private property because to them it is the abolition of their livelihood. Obviously, the average Marxist knows this is not the case. They know that the southern proletariat would be better provided for and kept out of poverty after the abolition of private property, but the average non-bourgeois southerner has not had access to theory which describes this. As Bakunin puts it, “They hate and fear those who would abolish private property, because they have something to lose – at least, in their imagination, and imagination is a very potent factor, though generally underestimated today”. And bourgeoisie leaders use this power of imagination to exploit and influence the southern proletariat. Along with a love for their leader, peasants are intensely patriotic just like the modern southern proletariat. People don American flags as clothing, they view the flag as some sort of deity to be worshiped, and they are ready to lay down their lives for a country whose interests are vested in monetary gain rather than their lives. Yet any shred of doubt about America causes disdain and upheaval within their communities. This is one of the reasons politicians are able to indoctrinate the southern proletariat so easily; they use their love of country against them. As Bakunin states, peasants are “egoistic and reactionary”. They are “petty landlords” clinging desperately to the small amounts of land they have; land that earns their livelihood (Bakunin). Yet, they still “hate the bourgeois landlords, who enjoy the bounty of the earth without cultivating it with their own hands”(Bakunin). So many southern proletarians mock the bossman behind his back as they desperately fight to put food on the table; they harbor socialist sentiments whether they like it or not. With this, Bakunin makes the point that peasants are “passionately attached to his land”; thus, making it easy to turn them against a foreign invader or anyone who poses a threat to their land. Hence, the patriotism that brews within the southern proletariat. Their land is their livelihood, it feeds their families, and their land is their country. And, as Bakunin observes, “while they are defending the land they are, at the same time, unconsciously but effectively destroying the state institutions rooted in the rural communes, and therefore making the Social Revolution”. Contrary to the thoughts of urban Marxists, the peasantry can be and is revolutionary. Yet, the average non-bourgeois southerner has an unrequited love for their leader: the president of the United States of America. Hence the conglomerates of “Trump 2020” and “Make America Great Again” flags which are abundant in the American south. Bakunin describes this loyalty as a “superficial manifestation of deep socialist sentiments, distorted by ignorance and the malevolent propaganda of the exploiters”. According to his logic, peasants will not donate their land, money, or lives to keep a ruler on the throne, yet they are willing to kill the rich and to take their property and give it to an emperor because they have a general hatred for the rich. Similarly, the modern southern proletariat guards their money and property so closely that they revere a leader like Trump for advocating for fewer taxes. They listen to Republicans’ calls for the people to keep their money, not knowing that the “people” the politicians speak of are the rich benefactors who donate to their campaigns. The rich keeping their wealth away from taxes overall does the opposite of what the southern proletariat wants, they just don't know this. They harbor socialist sentiments in their desire to make goods cost less, make necessities more available to them, and allow them to keep their hard-earned money; however, they listen to the pandering of politicians which convince them the way of accomplishing this is by giving more to the rich. Ronald Reagan's infamous “trickle-down economics” is a prime example of this. Bourgeois leaders do nothing but take advantage of the southern proletariat's desires for stability. While Marxists and the urban proletariat may view the southern proletariat as wrong, evil, or hypocritical, when they hold views that directly contradict their wellbeing as the working class, the true nature of their beliefs lies in their ignorance. As Bakunin states, “the peasants, like other Frenchmen, do wrong, not because they are by nature evil but because they are ignorant”. It is not the fault of the peasant that they are misinformed when no one provides them proper education. Just as it is not the fault of American southerners that their allegiances lie with politicians who directly contradict the wellbeing of the working class and with conspiracy theorists. They are misinformed because of a lack of comprehensive education in the American south. Criticizing them for this without acknowledging that their education is not prioritized, nor is it funded comprehensively by the government, is inherently classist. The bourgeois claim that superior education is what entitled them to dominate the city workers. The proletariat obviously disagrees, so why must the radicalized urban proletariat use the same logic to discredit their brothers in arms: the southern proletariat? After all, Bakunin was correct when he wrote that “the superiority of the workers over the bourgeoisie lies not in their education, which is slight, but in their human feelings and their realistic, highly developed conception of what is just”. The urban workers must recognize that the southern proletariat is not an enemy, but an ally. And they should be afforded the same resources as those in urban areas. Regardless of their ignorance, there is honest hope for the peasants: “alongside their ignorance there is an innate common sense, an admirable skillfulness, and it is this capacity for honest labor which constitutes the dignity and the salvation of the proletariat”(Bakunin). They are by no means useless in a revolutionary context. They struggle the same way as their more educated counterparts, they just need the extra hand from their urban brethren. Hence, the solutions Bakunin provides to the “peasant problem”. The urban proletariat and the peasantry tend to staunchly oppose each other just as the urban and southern proletariat tend to oppose each other. This stems from classism and elitism in the ranks of urban Marxists and the like. This alienation of two classes only causes infighting which makes the proletariat as a whole less powerful against the bourgeoisie and institutions of the state that operates in favor of it. Thus, although he was an anarchist, Bakunin poses many valid arguments and solutions to the alienation of the French Peasantry which can be applied to the modern, Southern Proletariat. Bakunin proposed an end to the elitism of urban Marxists and an end to the verbose nature of Marxist theory. Many people in the rural south lack proper education due to low funding and the American government's negligence; thus, when they are faced with a volume like Das Kapital, it seems overwhelming. Hence why, as Bakunin suggested, theory needs to be communicated in layman's terms. Urban proletarians cannot view themselves as superior to non-bourgeois southerners just because they are able to comprehend complex volumes of theory; this is counterproductive. It is inherently classist to look down upon those who cannot afford and lack access to higher education. If theory is communicated to non-bourgeois southerners in layman's terms, they may be able to see the truth in it and apply it to their lives. However, the only way this can be accomplished is through destigmatizing the elite nature of theory and making it more accessible to those who, through no fault of their own, are unable to comprehend it or devote time to decoding it. Urban Marxists also must not antagonize non-bourgeois southerners for their beliefs. They must not antagonize them for supporting a leader like Donald Trump, rather they should undermine the establishment through which the State and President wield their influence. As Bakunin put it, “the mayors, justices of the peace, priests, rural police, and similar officials, should be discredited” (Bakunin). The urban proletariat needs to not view themselves as better than non-bourgeois southerners simply because they are less ignorant. This view is ignorant in itself because the urban proletariat is using its education as a way of oppressing and putting down the less privileged which is almost identical to what the bourgeoisie does to the urban proletariat: “Because the city worker is more informed than the peasant, he often regards peasants as inferiors and talks to them like a bourgeois snob. But nothing enrages people more than mockery and contempt, and the peasant reacts to the city worker’s sneers with bitter hatred”(Bakunin). This classism and elitism do nothing but pit the urban and rural proletariat against one another, instead of against the bourgeoisie. Thus, although I am not an anarchist, Mikhail Bakunin makes excellent points in his 1870 work, “Letters to a Frenchman on the Present Crisis”. Points I believe modern, American Marxists can learn from. It is imperative to the success of our cause for us to band together as one working class. And the only way for this to be possible is to break down the animosity between the southern and urban proletariat; to recognize their revolutionary potential. The only way to do so is to make our ideology and our theory more accessible and to not make villains of the ignorant because of the government's negligence towards their education. Where there is fear and lack of education, there is potential for indoctrination. Anyone can become a victim. It is up to modern Marxists to amend this “peasant problem” and unite into one dictatorship of the proletariat. Works Cited Bakunin, Mikhail. “Letters to a Frenchman on the Present Crisis.” Works of Mikhail Bakunin 1870, https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/bakunin/works/1870/letter-frenchman.htm. Author Jae Satola is 18 years old and has been interested in Marxism for the past five years. They have a passion for making theory and education accessible to the masses. They hope to major in History in university and have a particular fascination with the Russian revolution and Eastern Europe. Archives December 2021 The Status of Women in Pre-Revolutionary Cuba Under the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, which lasted from 1952-1959, women lived under the yoke of a patriarchal society (Lamrani). They made up only 17% of the workforce, often being restricted to the role of mother and domestic caretaker; where they did work, they received much lower compensation than did men (Lamrani). From 1934 (pre-Batista) to 1958, only 26 women held governmental positions in all of Cuba (Lamrani). Women’s Involvement in the Insurrection In 1952, democratically elected president of Cuba, Fulgencio Batista seized total power of the island nation in a coup, suspending the 1940 Constitution, and establishing his rule as a fascist dictator, receiving recognition of legitimacy from the United States government (“Cuba: Timeline of a Revolution). In response to Batista’s dictatorship, many groups with varying ideologies engaged in revolutionary struggle against Batista before Fidel Castro’s 26th of July Movement succeeded in deposing him in 1959 (“Cuba: Timeline of a Revolution”). Among the multitude of anti-Batista groups were two all-women activist groups, the FCMM and the MOU, which were ideologically aligned with the centre-left party and Communist Party of Cuba respectively (Chase). These groups participated in civil protests and press denunciations against the Batista dictatorship, as well as organized support for a hunger strike carried out by political prisoners (Chase). The most significant revolutionary group, though, was Fidel Castro and Che Guevara’s 26th of July Movement, which succeeded in removing Batista from power and establishing Castro as the new leader of Cuba in 1959, after they seized control of Havana (“Cuba: Timeline of a Revolution”). The role of women within the 26th of July Movement was mostly (but not entirely) involved in underground support, which included strategizing, transmitting messages, providing safe houses, and transporting materials (Seidman). This was not their only role, though: Fidel Castro describes the revolutionary involvement of comrade Haydée Santamaría, who was directly involved in the insurrection, the same as were her male comrades: when being interrogated and tortured by Batista’s officers, Santamaría was told that they had killed her brother, to which she replied, “he is not dead; to die for one’s homeland is to live forever” (Castro, 47). Castro remarks on her revolutionary character: “never had the heroism and the dignity of Cuban womanhood reached such heights” (47). Certainly, there was a presence of women in the 26th of July Movement, even if they were outnumbered by their male counterparts (Herman). This can also be seen in the existence of an all-woman squadron within the Movement, called the Mariana Grajales (Lamrani). Women’s active involvement within the revolution, both in their own groups and within the victorious sect, set the stage for their increased role in post-insurrectionary Cuban society. The Feminist Elements and Victories of Revolutionary Cuba In the year following the end of the insurrectionary period of the Cuban Revolution, the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC) was founded by Vilma Espin, who was a revolutionary in the 26th of July Movement and wife of Raúl Castro (Lamrani). The Federation received support from Castro himself, as it sought to end discrimination in Cuba, and defend equality for all (Lamrani). Espin was devoted to the struggle for the emancipation of women and defending the revolution; the FMC’s webpage states: “from the start of the Cuban Revolution, the Cuban leadership has made concerted efforts to advance the status of women and increase their social and political participation, particularly through increased access to educational opportunities and employment” (The Federation of Cuban Women). One of the first objectives of the new Cuban government under Fidel Castro was the Cuban Literacy Campaign, a decidedly feminist policy which sought to eradicate illiteracy from the country (Herman). Castro announced his intention to make the population fully literate in 1960, less than one year into his leadership; illiteracy in Cuba at the time was at about 23.6% (Herman). The Literacy Campaign was carried out by volunteers, 55% of which were women, who taught children, adults, and the elderly students, who were 52% women, how to read and write (Herman). In 1961, just after the end of the year-long campaign, UNESCO declared Cuba to be the first territory free of illiteracy (Lamrani). Greater political actions for the protection of women were solidified by the new Cuban Constitution and the penal code, which created and protected equality rights for women, as well as gave them access to all public offices and joining the armed forces (Lamrani). Article 44 of the updated Cuban Constitution (1976) states: “the state guarantees women the same opportunities and possibilities as men in order to achieve women’s full participation in the development of the country” (The Federation of Cuban Women). In 1975, Cuba passed the Family Code, which was inspired by similar legislation from East Germany, which officially mandated the equal division of housework and childcare between spouses (Seidman). In a speech, Castro affirmed the Cuban state’s commitment to the goals of feminism: “the National General Assembly of the People of Cuba…condemns the inequality and exploitation of women” (Castro, 83). In 1965, Cuba became the first nation in Latin America to legalize abortion on request, making it the second nation ever to do so after the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in 1955 (Lamrani). Abortion was fully legalized in Cuba on four conditions which sought to protect women in the event; abortions had to be the women’s own choice, take place in a hospital, be carried out by trained professionals, and be completely free (Gonzalez). In 1989, Cuba’s National Center for Sex Education (CENESEX) was founded and led by the daughter of Raúl Castro and Vilma Espin, Mariela Castro (Hutchison). Cuba’s improvement regarding its treatment of queer people (as seen in the founding of CENESEX) is distinctly feminist because it contributes to a dissolving of gender-enforced boundaries in society. This feminist progression can also be seen in the fact that gender affirming surgery for trans people is completely free under the nation’s universal healthcare system (Hutchison). When feminist thinker Margaret Randall was forced to flee Mexico due to her involvement in the Mexican student movement, she found refuge in Cuba (Hutchison). Randall noted across her extensive writings that Cuban women used art such as theatre, poetry, music, and literature to challenge continuing sexist notions within the country’s society (Hutchison). Cuba was heavily involved in the movement to free Marxist feminist thinker and political activist Angela Y. Davis while she was being tried for a murder she did not commit in the 1970s, with Cuban officials and the FMC speaking out for her emancipation (Seidman). Both before and after her trial and subsequent acquittal, Davis visited Cuba many times, each time being celebrated for her ideology and identity as a Black Communist Woman (Seidman). She frequently had meetings with Cuban officials on her visits, during which she gave them advice and feedback on the status of women in their country; she once remarked: “the example of Cuba has confirmed that there cannot be a true emancipation for women without a socialist revolution” (Seidman). A similar sentiment to Davis’s idea that women’s emancipation and socialism must be founded together can be found in many speeches and writings by Castro himself: When discussions are held about the rights of women, of their aspirations, we see that there cannot be rights of women in our America or rights of children, mothers, or wives if there is no revolution. The fact is that in the world in which the American woman lives, the woman must necessarily be revolutionary. Why must she be revolutionary? Because woman, who constitutes an essential part of every people is, in the first place, exploited as a worker and discriminated against as a woman. (“Fidel Castro’s Speech at the Closing of the Congress of Women of the Americas”) Castro speaks to the idea that women can only begin to escape the twofold exploitation they face from capitalism and society through revolutionary socialism. The goal of the Cuban Revolution was not only to oust Fulgencio Batista as dictator of Cuba, but also to establish a socialist society built upon the ideals of Marxism, feminism, anti-imperialism, and equality. Castro remarked in a 1963 speech that the socialist elements of the new Cuba were visible in the changing identity of womanhood: “the bourgeois concept of womanhood is disappearing in our country. The concepts of stigma, concepts of discrimination, have really been disappearing in our country, and the masses of women have realized this” (“Fidel Castro’s Speech…”). That which was and is Lacking in Revolutionary Cuba Among the many victories for women and the ideology of feminism accomplished in the early years of the revolution and into the later years of its development, there were also areas which were lacking within the nation. Perhaps at the forefront, and an element which hindered further development for feminism was the assertion by Fidel Castro that Cuba had become a land totally free of gendered discrimination: “in our country, the woman, like the Negro, is no longer discriminated against” (Fidel Castro’s Speech…). Such a reductionist and provably false statement by the country’s leader was harmful in that it spread the untrue notion that sexism was an issue of the past in Cuba, which no longer needed to be dealt with, thus stalling further feminist progression. Similarly, the Federation of Cuban Women was centrally focused on fighting the discrimination against women which is inherent to the capitalist system, and generally did not acknowledge the distinct discrimination against women which existed in Cuban society, apart from the socioeconomic system of the nation (Seidman). Both within the FMC and in the broader scope of the Cuban government and people, defending the revolution and combatting US aggression were prioritized over issues regarding women for decades in Cuba (Hutchison). In terms of more concrete issues regarding the status of women in revolutionary Cuba: in the early years of the revolution, the government released a list of jobs which were considered unfit for women, likely because they constituted a threat to the health and safety of the female reproductive system (Hutchison). This list was reductionist in that it took the view that women should be precluded from working in certain areas of the labour force due to their reproductive abilities, essentializing them to their sex organs. Following the death of Fidel Castro in 2016, the list produced for his potential replacements contained only men, a fact which points to the still existing masculine dominance in the revolution in Cuba (Hutchison). Cuba Today Before an action plan can be provided for improving the future status of women in Cuba, a more modern look at the nation of Cuba must be offered so as to better understand the contemporary needs and wants of the Cuban women generally. Cuba’s Labour Code provides women the right to full salaries while taking a month and a half off before delivery of a child, and three months off after childbirth; this leave may be extended to a full year with compensation equivalent to 60% of regular earnings (Lamrani). Cuban women make up the majority of union leaders, and are required by law to be compensated equally to men (Lamrani). Also in the field of labour, Cuban women make up only 44% of the national workforce, a figure which illustrates the need for further institutional equality and job programs (Lamrani). In the areas of health and education, Cuban women make up 60% of the country’s students and 65% of its graduates (Lamrani). In 1960, just after Castro came to power, the life expectancy for Cuban women was 65.62 years; by 2019, it had risen to 80.78 (The World Bank). Comparatively, the life expectancy for women in the US in 1960 was 73.1 years, more than 7 years greater than Cuba. However, for women in the US in 2019, life expectancy is less than one year greater than that of Cuban women, at 81.4 years (The World Bank). Women still are entitled to free abortion on request (Gonzalez), and to free gender affirming surgery (Hutchison). In the political arena, Cuba ranks second out of every nation worldwide for most women elected to their national parliament, only after Rwanda (Archive of Statistical Data). Cuba has a single house national assembly, in which 322 of the 605 seats were represented by women in February 2019, making up 53.2% of the house (Archive of Statistical Data). As of October 1, 2021, female representation in the Cuban National Assembly of the People’s Power was increased to 53.4% (IPU Parline). It also should be mentioned again that, though women make up majority of the elected Cuban assembly, no women’s names were present on the shortlist to replace Fidel Castro as First Secretary after his death in 2016 (Hutchison). Policies for the Betterment of Cuban Women Women’s involvement in the labour force in Cuba remains an issue, with one 2020 study estimating that just 38.44% of Cuban women work; although this is a much greater number than was the case in as recent as the 1990s, there remains work to be done (Trading Economics). This is an issue which could potentially be solved by the introduction of a guaranteed jobs program in Cuba, something which existed in the earlier years of the revolution, but which was abandoned later on; by guaranteeing work for all Cuban citizens, women would more easily find representation in the national workforce (New York Times News Service). Other issues which may arise against the progression of Cuban women should be combatted by the FMC, an organization and community of revolutionary women. This, however, would be difficult unless the FMC begins to acknowledge sexism as present in Cuban society, rather than just within the context of global capitalism (Seidman). The Federation of Cuban Women should reform itself to recognize discrimination against women as present in all areas of life. Politically, women in Cuba have found full involvement in the National Assembly and in other government organizations such as the FMC, but, as previously mentioned, no women were considered for replacing Fidel Castro as First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba following his death in 2016 (Hutchison). This fact points out the need for women’s continued involvement in the revolutionary process, which can be accomplished by celebrating the feminist victories and acknowledging the failures of the ongoing revolution. It can also be directly achieved by adding politically exceptional women to the potential replacements for the position of First Secretary once Raúl Castro dies. Long Live the Revolution The most critical component for continuing feminism on the island nation of Cuba is the continuation of the revolution. Socialism in Cuba ousted a great deal of the capitalistic oppressions which existed there. Just the same, the revolution eliminated much of the discrimination faced by women thereto. The socialist ideology of the Cuban government and people is a necessary force for both maintaining the currently existing feminism in Cuba, and for improving the status of women in Cuba in the future. In order for women’s lives in Cuba to better, the revolution must be defended. Michael Parenti describes the manner in which rights for women were near abolished after the fall of socialism in the Soviet Bloc: The overthrow of communism has brought a sharp increase in gender inequality. The new constitution adopted in Russia eliminates provisions that guaranteed women the right to paid maternity leave, job security during pregnancy, prenatal care, and affordable day-care centres. Without the former communist stipulation that women get at least one third of the seats in any legislature, female political representation has dropped to as low as 5 percent in some countries. In all communist countries about 90 percent of women had jobs in what was a full-employment economy. Today, women compose over two-thirds of the unemployed. (114-5) Parenti’s analysis of the fall of the status of women in tandem with the fall of Soviet socialism is a warning to Cuba; socialism exists in parallel with women’s rights, and the elimination of one implies the death of the other. There should also be a point made here as to the alternative option to socialism, which is only capitalism: there is either capitalism or socialism/communism. No third ideology can be created, and thus, no liberation for women can be accomplished elsewhere than socialism. “Since there can be no talk of an independent ideology being developed by the masses of the workers in the process of their movement the choice is: either bourgeois or socialist ideology. There is no middle course” (Lenin, 82). The Cuban Revolution was a force which brought about massive social, economic, and political progression for the status of women, and only by consolidating that revolution in future generations can those victories be maintained and progressed. Works Cited Archive of Statistical Data. "Women in National Parliaments." 1 February 2019. archive.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm Castro, Fidel. The Declarations of Havana. 2008. Verso Books, 2018. Chase, Michelle. "Women's Organisations and the Politics of Gender in Cuba's Urban Insurrection (1952-1958)." Journal of the Society for Latin American Studies, vol. 29, no. 4, 2010: 440-458. “Cuba: Timeline of a Revolution.” Aljazeera News, 2009. aljazeera.com/news/2009/7/26/cuba-timeline-of-a-revolution The Federation of Cuban Women. “Women and the Cuban Revolution: The Federation of Cuban Women.” cubaplatform.org/federation-cuban-women “Fidel Castro’s Speech at the Closing of the Congress of Women of the Americas (1963).” marxists.org/history/cuba/archive/castro/1963/01/16.htm Gonzalez, Ivet. "Abortion Rights in Cuba Face New Challenges." Havana Times, 2017. havanatimes.org/features/abortion-rights-in-cuba-face-new-challenges/ Herman, Rebecca. "An Army of Educators: Gender, Revolution, and the Cuban Literacy Campaign of 1961." Gender and History, vol. 24, no. 1, 2012, 93-111. Hutchison, Elizabeth Quay. "Women, Gender, and Sexuality in the Cuban Revolution." Radical History Review, 2020, 185-197. IPU Parline. "Monthly Ranking of Women in National Parliaments." November 2021. data.ipu.org/women-ranking?month=10&year=2021 Lamrani, Salim. "Women in Cuba: The Emancipatory Revolution." The International Journal of Cuban Studies, vol. 8, no. 1, 2016, 109-116. Lenin, Vladimir I. “What Is To Be Done?” Essential Works of Lenin, edited by Henry M Christman, Dover Publications, 1987. New York Times News Service. "In Radical Move, Cuba Ends Guaranteed Jobs." Chicago Tribune, 1995. chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1995-05-14-9505140359-story.html Parenti, Michael. Blackshirts and Reds: Rational Fascism and the Overthrow of Communism, City Lights Books, 1997. Seidman, Sarah J. "Angela Davis in Cuba as Symbol and Subject." Radical History Review, 2020, 11-35. Trading Economics. "Cuba - Labour Force, Female." Trading Economics, 2020. tradingeconomics.com/cuba/labor-force-female-percent-of-total-labor-force-wb-data.html The World Bank. "Life Expectancy at Birth, Female (Years)" The World Bank, 2019. data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.FE.IN?locations=CU Author Nolan Long is a Canadian undergraduate student in political studies, with a specific interest in Marxist political theory and history. Archives December 2021 When we think of farmers we tend to reflect on a time when farmers grew their own crops in their own land and used those crops in turn to exchange for seeds. Due to this capacity for exchange many farmers were able to trade and grow varieties of the same crop. Unfortunately, because of big seed monopolies like Monsanto and their seed manipulation technology it has been made illegal for farmers to exchange and trade seeds with one another. As Vandana Shiva states in Stolen Harvest “The perverse intellectual-property-rights system that treats plants and seeds as corporate inventions is transforming farmers’ highest duties-to save seed and exchange with seed with neighbors-into crimes. Further, seed legislation forces farmers to use only “registered” varieties” (Shiva, p.90). As Monsanto and other seed monopolies keep growing and gaining control over the agricultural industry it is becoming almost impossible for farmers to make a living off farming alone. As a result, many farmers end up feeling disconnected from their labor, their land, and their cultural livelihood. This has led to increasingly disturbing rates of depression and suicide amongst these communities. Suicide rates amongst farmers has been exponentially increasing over the years as many of them have been drowning in debt. Monsanto and similar agriculture companies take advantage of their power, increase their prices on planting seeds, and make it necessary to invest in pesticides. Forcing farmers into the uncomfortable position of being between a rock and a hard place, they subsequently price gauge the pesticides their activities forced farmers to invest in. While knowing their seeds do not always bear offspring reliably (since some of the seeds are modified to be sterile), they nonetheless force these upon farmers who find that, since the seeds usually do not reproduce, in the case of a harvest failure they lack enough crops to provide for their means of subsistence. When this difficulty presents itself, the usual thing farmers are forced to do is take out loans. However, because of this same instability, if the following season the same thing happens, not only do farmers find themselves in a position unable to pay for the necessaries of life, but also unable to pay for the debts that were accumulated thanks to debt acquired in prior, sterile seeds caused failed harvests. This seed manipulation, and the effects it brings about, are at the core of the aforementioned increase in farming communities’ rates of depression and suicides. However, it is not merely the lives of the farmers which are affected by these profit-driven practices; the effects these seeds have on the soil, on the life forms that live off this soil, and on the general, natural metabolisms of a given place are extraordinarily destructive. As stated by Vandana Shiva in Stolen Harvest “The gradual spread of sterility in seeding plants would result in a global catastrophe that could eventually wipe out higher life forms, including humans, from the planet” (Shiva, p.83). Unfortunately, the melancholic news we encounter when we look into the lives of farming communities seems to be just the tip of the iceberg if these practices continue. With the climatic instability being brought about through climate change, the prices of farming tools and equipment on the rise, and the amount of debt that these farmers have been forced to accumulate, it is only natural that their lives exist in a constant state of desperation, anxiety, and ultimately, despair. The options this systematic cornering leaves farmers to choose amongst are 1) either sell their farm, and in so doing, say goodbye to the forms of life they have generationally participated in, the forms of life that have brought meaning, tranquility, and happiness to them, their parents, grandparents, etc.; or 2) say goodbye to life altogether. Their options, in essence, are reduced to this – live a life in which what you found meaningful has been anihilated from your everyday existence or live no life at all. As stated in an article titled ‘Midwest farmers face a crisis. Hundreds are dying by suicide,’ “Farmers [in the United States] are among the most likely to die by suicide, compared with other occupations, according to a January study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The study also found that suicide rates overall had increased by 40% in the last two decades. This alarming suicide rate is not just in the United States but in other parts of the world too. In 2014 it was reported by People's Archive of Rural India in an article entitled ‘Maharashtra crosses 60,000 farm suicides’ that “a total of 296,438 farmers have committed suicide in India since 1995”. In the less than 20 years from 1995 to 2014, India saw an average of 40 or so deaths by suicide a day. In a rich state such as Maharashtra there are “over ten farmers’ suicides every single day [over] these past ten years in a row”. In sum, as Vandana Shiva says, “these increased cost can push farmers into bankruptcy and even suicide” (Shiva, p.101). Shiva states in an article for Countercurrents entitled ‘Farmers Suicides: What Is Causing Them, And What Can Be Done To Stop The Tragedy’ that “Our food system needs to change. Ecological agriculture, seed sovereignty, and climate resilient strategies form the roadmap for this change”. To do this, however, requires a radical shift away from neoliberal capitalism, a shift away from “corporate control and corporate profits, which are made possible by the corporate written rules of ‘free’ trade, trade liberalization, and globalization”. Seed sovereignty is incompatible with a system premised on expanding profits. As anthropologist Samantha Fox argued, “Climate change is an outcome of our current social organization. It threatens all of humanity. Altering our current social organization offers the possibility of creating a society-in-nature where all life is valued”. Although the facts present a stark reality, it is, nonetheless, as a human-created reality, changeable. At the end of last year more than 250 million Indian farmers participated in the “biggest organized strike in human history”. Workers joined with farmers in collectively fighting back a system which prioritizes profits over people and planet. These protests, of course, saw the repression of the tyrannical hand of capital – the state and its police forces. However, it showed that people are no longer willing to accept the existing conditions. Further, it showed that this dissatisfaction has reached a point where activity and protests become inevitable. The result? After a year of struggling, the farmer won! For similar movements the question will now be, how well can protesters be organized, how well can spontaneous activity be used to conduce actual change, and not simply dissipate within a few weeks? In conclusion, the seed monopolization and the disastrous effects it has on farming communities is necessarily interlinked with the struggle against imperialism, capitalism, and climate change. One cannot expect people and planet friendly results from a system which prioritizes profits over people and the planet. A radical transformation is necessary, of this, ecologists almost all uniformly agree. The extraordinary examples of food sovereignty seen in socialist Nicaragua, Cuba, and others show that when a government is controlled by workers and peasants it can fight climate change in a manner which balances sustainability with increased standards of living which facilitate human growth and flourishing. A change for the better is possible, but only because moving beyond a capitalist mode of production and state is too. References Shiva, V. (2016). Stolen Harvest: The Hijacking of the Global Food Supply. University Press of Kentucky . AuthorLeslie A. Gomez is a senior philosophy major in Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. She is interested in Marxist feminism and ecology. Youth League Archives December 2021 To understand the Cuban Embargo, one must understand that it is only one aspect in the broader goal of America to rule over Cuba. The US has long had an interest in colonizing Cuba. In 1823, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams wrote a letter to U.S Minister to Spain Hugh Nelson about the possibility of annexing Cuba within the next fifty years. The Cuban sugar industry at that time had been incredibly lucrative and drew the attention of American investors. Twenty five years later, in 1848, James Polk offered to buy Cuba from Spain for $100,000,000. This offer was rejected. Though the US may have never formally colonized Cuba, its economic domination of the island could be comparable to that of any colonial power. By the 1870s, 75% of Cuba’s sugar was exported to the US. In 1895, US investments in Cuba were valued up to $95,000,000. Cuba’s industries and economy quickly became subordinated to US corporations. In 1894, 90% of Cuba’s exports went to the US and 38% of its imports were from the US. Cuba served as a valuable geopolitical outpost for the US. It would be valuable in defending Florida and New Orleans, along with serving as an outpost and springboard for further economic and political control of Latin America. While Cuba might have technically gained independence from the US in 1902, the Platt Amendment, however, kept Cuba in a continual state of colonial subjugation. The Platt Amendment allowed the US to intervene in Cuba at any time. It also set up US control of Cuba’s foreign policy and its public finances. In addition, much of Cuba’s wealth remained in US hands. In essence, the Platt Amendment and the presence of US corporations reduced the notion of Cuban independence to a myth. By the 1920s two thirds of Cuba’s sugar production was controlled by US companies and in 1929, US investments in Cuba reached almost a billion dollars and 62% of it went into the sugar industry. By the 1950s Cuba was the largest recipient of US aid and the US controlled almost all the important industries in Cuba. By 1955, 90% of telecommunications and electric services, 40% of the sugar industry, and 50% of public service railways were in the hands of American investors. Four years later, the US controlled 90% of all the mines, 80% of the utilities, and almost all the cattle ranches and the entire oil industry. However, this vast investment in Cuba did not benefit the majority of Cubans, instead much of this wealth was repatriated back to the US or consumed by the American and Cuban elites on the island. That’s not to forget of course that US investment in Cuba heavily favored multinationals, and many of these corporations didn’t have to pay taxes to the Cuban government and were allowed to keep their profits, thus doing very little to develop an independent Cuban economy or help the lives of everyday Cubans. In fact, life for everyday Cubans was quite miserable under Batista and American imperialism. In 1953, the average Cuban family made six dollars a week and 15-20% of the labor force was unemployed. The average salary of a rural Cuban was $91. Sugar companies also owned 75% of the arable land and only employed 25,000 people full time and 500,000 people as part time workers during the harvest season which only lasted for about two to four months, for the rest of the year these people were relegated to poverty and unemployment. Only 2% of people in Cuba had running water and 9% of people had electricity. The vast majority of people in the rural areas lived in huts. The life expectancy was 59 years and infant mortality was 60 out of 1000 live births. The notions that Cuba prior to Castro was a ritzy tropical paradise couldn’t be further from the truth. The vast majority of the population lived in poverty and a system of racial segregation--as horrible as the one in the US if not worse--was institutionalized and barred Afro-Cubans from accessing any employment opportunities other than domestic or manual labor. The only people who truly benefited from Batista’s Cuba were white wealthy landowners, business elites, and the professional class. These were the people that fled immediately after the revolution, not common workers or campesinos. The Cuban revolution was a true revolution of independence. It freed Cuba from the neo-colonial clutches of the United States which subjected the Cuban economy to the whim of monopolistic expansion by American corporations. There is no political independence without economic independence. Castro’s land reform and nationalization of major industries allowed Cuba to buck the reins of US imperialism and chart its own path of development without the destructive interference of an imperialistic power. The US sees an independent Cuba as a threat to its grasp over the rest of Latin America and its own status as a global hegemonic power. Therefore, it can’t let Cuba’s socialist development succeed. Though the US has attempted various methods to sabotage the development through means of terrorism and assasination, the Embargo, otherwise known as the blockade has been the most enduring inhibitor to a prosperous and socialist Cuba. The blockade is incredibly thorough and applies not only to U.S. nationals and businesses based in the United States but also to businesses and nationals outside of the US as well. References https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/speech-senator-john-f-kennedy-cincinnati-ohio-democratic-dinner https://kawsachunnews.com/the-defense-of-the-cuban-revolution-is-a-struggle-against-fascism https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/kencuba.htm https://cri.fiu.edu/us-cuba/chronology-of-us-cuba-relations/ https://www.jstor.org/stable/2009288?seq=2#metadata_info_tab_contents https://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/hernandez.html https://www.ourdocuments.gov/print_friendly.php? flash=false&page=&doc=55&title=Platt+Amendment+%281903%29 AuthorN.C. Cai is a Chinese American Marxist Feminist. She is interested in socialist feminism, Western imperialism, history, and domestic policy, specifically in regards to drug laws, reproductive justice, and healthcare. Archives November 2021 |

Details

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

About the Midwestern Marx Youth LeagueThe Midwestern Marx Youth League (MMYL) was created to allow comrades in undergraduate or below to publish their work as they continue to develop both writing skills and knowledge of socialist and communist studies. Due to our unexpected popularity on Tik Tok, many young authors have approached us hoping to publish their work. We believe the most productive way to use this platform in a youth inclusive manner would be to form the youth league. This will give our young writers a platform to develop their writing and to discuss theory, history, and campus organizational affairs. The youth league will also be working with the editorial board to ensure theoretical development. If you are interested in joining the youth league please visit the submissions section for more information on how to contact us!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed