|

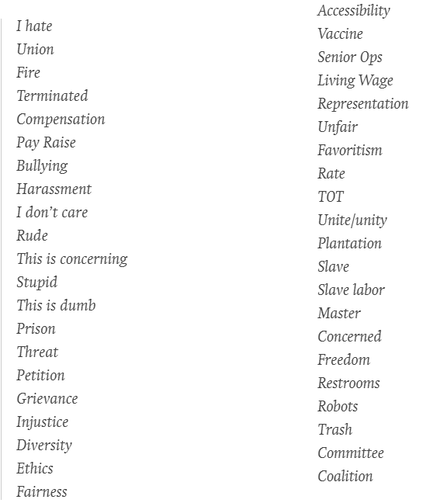

7/27/2022 Contemporary Union Busting: How Software and the Irrationality of Capitalism Collapsed the Modern Labor Movement. By: Vaughn MitchellRead NowAppleton, Wisconsin Starbucks baristas link arms in solidarity (wearegreenbay.com/news/local-news/partners-have-been-struggling-to-stay-afloat-appleton-starbucks-baristas-unionize/) I had recently finished my Sophomore year of high school when I decided to apply for my first job. There was an opening at Meijer, a popular grocery store found all throughout the Midwest and conveniently in a town bordering my own. Because I had never applied for a job before, I really tried to sell myself on this application, and luckily, I received a call to come in for an interview a couple days later. The position was stocking shelves inside, but I learned in my interview that they don’t allow anyone under 18 to work in the store for safety concerns. What I had thought was a pro-labor move on Meijer’s behalf to protect me from falling items on the shelves and rather spare me for the parking lot that I later found was surrounded by moving cars and blistering 90 degree heat, I was naively satisfied with what would be my new job. I was set to start the next week, late June, and first had to watch some training videos that verified I could work with the utmost indispensable knowledge for the laborious job of cart-pushing. These videos, though, had some caveats. Most significantly, I was strongly encouraged not to join a union: “Before you read any documents pertaining union membership, please understand that they can be filled with deceptive conditions meant to steal your signature that offer little benefits.” Though I don’t work there anymore, I look back on that summer with a grin on my face hearing that all new Meijer employees are automatically registered [1] for membership and represented by the United Food and Commercial Workers Union as of 2022. This was a completely novel strategy that had opened my eyes to modern union busting, and my experience watching those videos at Meijer parallels many other corporations like Walmart, Starbucks, and most infamously, Amazon. A 2018 training guide [2] sent to Whole Foods management, now subsidiaries after being bought out by Amazon, discusses the company’s anti-union sentiments. This mandatory training video explicitly mentions to new employees that "unions pose a threat to this direct connection [between associates and employers]. This commitment to a direct connection with our associates makes union representation unnecessary...we do not believe unions are in the best interest of our customers, our shareholders, or most importantly, our associates." Amazon has also been responsible for airing anti-union advertisements targeting locations that have petitioned the National Labor Relations Board for a vote. Take Bessemer, Alabama, where Amazon's advertisement [3] had led to a failed union vote. Even after the NLRB had authorized another vote after finding these advertisements strongly interfered with Amazon workers’ ability to unionize, the damage had been done, and Bessemer workers had lost the vote a second time [4]. This was nothing unexpected, of course. However, another aspect of this training video presents itself as a laughable and ironic practice for Amazon’s labor policy. Verbatim, "Employee actions in non-union workplaces can be protected...examples would include an employee demanding an increase for all associates or complaining about a work rule that impacts his or her co-workers...associates have the right to discuss their opinions on unions in the workplace at any time." Where’s the irony? Well, a report [5] from The Intercept in April 2022 discusses Amazon’s plans to create an internal chatting service called “Shout-Out” that allows employees to recognize each other for good performance. This program would award “virtual stars” and “badges” for productivity, essentially another way of obfuscating the role of the wage in the worker’s life by replacing an unnecessary reward system that negates the need for pay raises. With this program, instead of compensating for higher productivity, you are acknowledged for it – the chief reason for anticipated resentment to this program. Consequently, this meeting also examined filtering language included in worker’s messages often negatively directed at management. Although a limitation on profanity can be necessary for some phrases on this chatting software, a list of flagged keywords compiled by The Intercept go above and beyond foul language. The lines between profanity limits and deliberate censorship on organization become blurred. The contradiction of Amazon’s simultaneous allowing non-unionized workers to discuss working conditions as recognized in their training video and blacklisting of words such as “compensation”, “pay raise”, “concerning”, “petition”, “living wage”, among others, speak to Amazon’s wavering neutrality and denigration of labor organization. While programs and applications like Amazon’s “Shout-Out” can contribute to the breakage of solidarity before workers can even get the chance to organize, another frequently underestimated factor that grips the modern labor movement by its feet is capitalism’s endless pursuit of profit. Simply put, large corporations find it more profitable to abandon sectors of their provided services or even locations of operation altogether if the threat of unionization exists. One example of the prior occurred in 2000 when Walmart meat-cutters successfully won a union vote in Jacksonville, Texas. Shortly after the vote, Walmart announced [6] a full transition from freshly-cut meat to packaged meat only. These butcherers, like Meijer employees as of 2022, were also represented by the United Food and Commercial Workers Union until the positions were removed by Walmart. Walmart repudiated these union benefits by abolishing the positions set to receive them. Perhaps a more recent example of the latter - abandoning locations of operation - has occurred with Starbucks. This coffee and cake-pop business has recently energized employees in union surges across the country, and Starbucks Workers United (SWU) has influenced more than 180 stores to unionize so far. Just like Walmart decided to obstruct union membership of butcherers in 2000, CEO of Starbucks Howard Schultz follows the same pattern today, declaring that 16 Starbucks locations are set to close due to community-related incidents that hinder the operation of each location. He cites in a video [7] released on July 13th that the closures result from violence and crime near the communities the Starbucks’ are placed in and frequent drug use that occurs in Starbucks bathrooms. A mere recognition that these locations are closing does not suffice. SWU notes "Every decision Starbucks makes must be viewed through the lens of the company's unprecedented and virulent union-busting campaign.” [8] Although Schultz clarifies that the company will not be closing locations that “aren’t unprofitable”, it’s no coincidence that 2 of the 16 Starbucks locations set for closure are already unionized, and another one is set for a vote this August. The precise difference between Starbucks’ and Walmart’s union busting strategies is that Starbucks has taken a thinly veiled anti-union position by justifying their closures with the disruptions in the workplace that the surrounding communities cause; on the other hand, Walmart blatantly disrupted union membership by slashing the need for the meat-cutters’ branch entirely. Both union busting practices of Walmart and Starbucks serve to develop the irrationality of capitalism. This irrationality and inherent contradiction of the traditional capitalist enterprise lies in Walmart and Starbucks halting their productive forces, whether it be workers like the butcherers of Walmart or entire locations like the 16 Starbucks spots (of which those workers also live in precarious situations and will likely be jobless if not relocated). A system designed for the purpose of profit and profit only has molded itself into a new form as a means to preserve its share of the yield even at the expense of workers who fight tirelessly for a fraction more. Admittedly, examining individual events like these can appear minuscule in the entire context of the modern labor movement. Sure, the optimistic left may say “It’s just one union that was busted, worker solidarity is strong elsewhere!” Though pessimism is not optimal either, that does not preclude the ability to remain wary. Although a Gallup poll [9] conducted in September 2021 found that 68% of Americans support labor unions, private sector union membership has been steadily declining since the rise of neoliberalism that has demonstrably impacted the strength of organization. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, that figure [10] of unionized Americans stands at 10.3% as of 2021. It goes without saying that Walmart’s abolition of unionized positions in 2000, Starbucks’ closing of unionized locations most recently, Amazon’s condemnation of a unionized workplace through their training videos, advertisements, and software designed to break the bonds of worker solidarity, and more personally, Meijer’s anti-union training procedures all function as pillars that bolster the hierarchical relations that characterize capitalism. So, yes, every union vote counts whether you’re a well-to-do Starbucks barista in college making some extra cash or a single mother of 2 children working at Bessemer’s Amazon facility. Having seen coworkers all across the spectrum, the common denominator is that we are all replaceable cogs in the machine. And although it sounds trite, unions offer strength in numbers that is unparalleled to any downsizing, any piece of technology, any advertisement, or any capitalist function that serves to suppress the power of organized labor. Solidarity to all who produce. Works Cited: [1] Thomas, Marques. “Is Meijer Unionized in 2022? (All You Need to Know).” QuerySprout, 4 Apr. 2022, https://querysprout.com/is-meijer-unionized/. [2] “Amazon's Union-Busting Training Video (Long Version).” YouTube, 22 June 2019, https://youtu.be/uRpwVwFxyk4. [3] “Amazon Is Running This Anti-Union AD to Combat Organizing Efforts.” YouTube, 23 Feb. 2021, https://youtu.be/Pp76Bp0jGOE. [4] Palmer, Annie. “Amazon Workers in Alabama Reject Union for Second Time, but Challenged Ballots Remain.” CNBC, CNBC, 31 Mar. 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/31/amazon-workers-in-alabama-reject-union-for-second-time.html [5] Klippenstein, Ken. “Leaked: New Amazon Worker Chat App Would Ban Words like ‘Union," ‘Restrooms," ‘Pay Raise," and ‘Plantation.’” The Intercept, The Intercept, 4 Apr. 2022, https://theintercept.com/2022/04/04/amazon-union-living-wage-restrooms-chat-app/. [6] Swoboda, Frank. “Wal-Mart Ends Meat-Cutting Jobs.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 4 Mar. 2000, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/2000/03/04/wal-mart-ends-meat-cutting-jobs/acdb8f7c-d7c2-4e31-aad7-8f690ba3b35b/. [7] Hoffman, Ari. “Howard Schultz on Closing 16 Starbucks Locations.” Twitter, Twitter, 13 July 2022, https://twitter.com/thehoffather/status/1547308330929963008?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1547308376765263872%7Ctwgr%5E%7Ctwcon%5Es2_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fnypost.com%2F2022%2F07%2F18%2Fstarbucks-ceo-howard-schultz-blames-democrat-run-cities-for-store-closures%2F. [8] Corrigan, John. “Starbucks to Close Even More Stores.” HRD America, HRD America, 19 July 2022, https://www.hcamag.com/us/specialization/industrial-relations/starbucks-to-close-even-more-stores/413713. [9] Brenan, Megan. “Approval of Labor Unions at Highest Point since 1965.” Gallup.com, Gallup, 20 Nov. 2021, https://news.gallup.com/poll/354455/approval-labor-unions-highest-point-1965.aspx. [10] United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Union Members-2021” News Release, U.S. Department of Labor, 20 Jan. 2022, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/union2.pdf AuthorVaughn Mitchell is a high school senior living outside Chicago. His political interests include the development and origins of labor unions, abolition movements in the 20th century, and the Land Back movement. After his final year of high school, he hopes to study data science and political science on the East Coast. Archives July 2022

0 Comments

7/18/2022 Rape Myths, White Supremacy, and the Carceral State as Tools of American Neoliberalism. By: Emely MendezRead NowAsk any woman you meet, old or young, and she’ll tell you the reigning piece of advice that she’s been given time and time again; don’t get raped. Of course, rarely are we told such a thing so bluntly. The message is hidden in frequent warnings to not accept drinks from strangers, not drink too much at parties, not walk home alone, and not wear too-short skirts; all things meant to deter a scary man from jumping out of the bushes and attacking you. While many women follow this advice religiously, it still hasn’t done much to stop them from being victimized by rape or sexual assault due to the often unacknowledged fact that many perpetrators are people the victims knew personally. These conversations about deterring rape through individual action are often ineffective because the narrative doesn’t fit the reality. Although it seems like society is oh-so concerned over violence against women, victims are often left unseen and unheard when they seek justice against their perpetrator due to the frequent mishandling of rape cases by the criminal justice system. The reality is that the United States government does not and has never cared for protecting women, only for protecting its own interests. The threat of violence against women is but a convenient tool manipulated against the public to justify the police state, mass incarceration, and the racist criminalization of African American men and non-white immigrants – actions that ultimately enforce the hegemony of White Supremacy and the bourgeois capitalist class. Rape myths have been used as political tools in the United States for much of modern history, predominantly as a form to uphold White Supremacist and Patriarchal ideals. Deniers of the prevalence of rape culture argue that American society has always been morally appalled by rape, however the reality is rape is only taken seriously when it can be manipulated to support the power of oppressive groups. If rape truly were to be taken seriously in the United States, then it wouldn’t be the case that less than 1% rape investigations end in incarceration for the perpetrator (Van Dam 2018). Further, the mainstream conversation surrounding sexual violence is often centered on the very specific situation of a woman being attacked by a predatory stranger on the street when the reality differs drastically. According to the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network, “8 out of 10 rapes are comitted by someone known to the victim.” (RAINN 2022). Victims of rape and other forms of sexual violence often have to tell their stories to a public that has been led to view rape as a randomized attack. When victims who were familiar with their aggressor come forward, they often have to deal with a line of questioning that perpetuates the idea that the victim was somehow inviting the assault. This nationwide misconception of sexual violence is often an influencing factor in cases like that of Brittany Smith, an Alabama woman who was sentenced to 20 years in prison for killing her agressor (Fruen et al 2020). The presiding judge over the case argued that Ms. Smith couldn’t definitively prove rape as she was the one who had invited her assailant into her home in the first place and hadn’t explicitly asked him to leave (Gill et al 2020). The data on the reality of rape and sexual violence in the United States has not stopped American politicians from parroting rape myths in order to push certain forms of legislation, however. Conservative Republican officials and gun rights lobbyists over the past decade have been strong supporters of “Stand Your Ground” legislation, which allows for the use of deadly force as an act of self-defense in certain cases in which a person has no “duty to retreat” prior to the use of force (NCSL 2022). “Stand Your Ground” legislation has been controversial for much of its presence in American mainstream politics due to its use in the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the 2012 murder of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed Black teenager shot by Zimmerman on his way home from the convenience store. Zimmerman’s lawyers did not use the “Stand Your Ground” defense in particular, but his defense was dependent on the precedent set by that legislation (Coates 2013). Right wing proponents of “Stand Your Ground” legislation came to rely on rape myths and misconceptions of sexual violence in order to defend these laws against the onslaught of opposition. In support of “Stand Your Ground” legislation, Florida politicians Don and Matt Gaetz and NRA lobbyist Marion Hammer argued that the legislations’ opposition were “‘anti-woman,’” as these laws would ultimately aid women who defend themselves against a would-be rapist (Franks 2014). As seen in the case of Brittany Smith, however, “Stand Your Ground” has not been very effective in this sense. Rape myths and the threat of sexual violence against women has also been heavily influential in upholding White Supremacy for much of American history. The myth of the Black male rapist dates back to the abolition of slavery and the Reconstruction Era South, in which White Supremacists sought a justification for lynchings and mass incarceration. Black men were painted as brutal and “savage” caricatures by White men, “the claim that black brutes were, in epidemic numbers, raping white women became the public rationalization for the lynching of blacks.” (Pilgrim 2000). Arguably the most well-known instance of lynching in the United States is that of young Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy brutally murdered by a White mob for whistling at an older White woman whom admitted decades later she’d fabricated the interaction (Perez-Peña 2017). Over the course of modern history following the abolition of slavery, the myth of the “black brute” has led to black men experiencing higher rates of incarceration than any other racial demographic. According to the NAACP, African Americans experience 5x the rate of incarceration of White Americans and made up 34% of the correctional population in 2014 (NAACP 2022). The myth of the Black male rapist was influential in the convictions of the infamous Central Park Five case, in which five Black teenage boys were wrongfully convicted and incarcerated for the gang rape of a White woman in NYC’s Central Park (Duru 2004). Generation after generation of Black men have been chewed up and spit out by the American carceral system with the threat of sexual violence as a convenient justification for it all. In what has arguably become known as a second Civil Rights Movement, Black activists in the past decade have pointed to mass incarceration as a continuation of slavery, with Ava DuVernay’s Oscar winning 13th documentary being a major part of the conversation surrounding mass incarceration. Although the 13th Amendment does, in fact, legalize slave labor as a condition of incarceration, less than 1% of incarcerated individuals are employed by private companies (Sawyer et al 2022). While labor exploitation is part of the suffering inflicted by mass incarceration, the forced idleness of incarcerated individuals has a much broader impact. The masses of Black men sitting in prisons not only serves to keep the Black population subjugated, but also to maintain a certain level of poverty and unemployment in the U.S. that weakens the bargaining power of the working class. Neoliberal economic policy in the United States over the past 40 years has been centered on limiting labor power as much as possible, as seen in the steady decrease of union membership across the nation which coincides with the rise of American companies engaging in offshore manufacturing (Vachon 2013). The United States’ particular brand of transnational capitalism is reliant on maintaining a certain level of unemployment within the country. The cost of labor in the U.S. deters American companies from making a return to domestic manufacturing, and in order to avoid a rise in wages and a subsequent profit squeeze for companies that do hire American laborers, the state must avoid a too-low unemployment rate. Forced idleness is a major issue in American prisons, with the Brennan Center for Justice arguing that it is one of the main sources of prison violence (Hopwood 2021). Further, the forced idleness perpetuated in prisons reinforces a high rate of unemployment and recidivism for formerly incarcerated individuals. According to Phillipe Bourgois’s “Lumpen Abuse: The Human Rights Costs of Neoliberalism,” the criminal records of formerly incarcerated individuals, “exacerbated by a low skill level imposed by years of forced idleness in a purposefully hostile carceral environment condemns them to chronic unemployment upon their release from prison.” (Bourgois 2011). The criminalization of Black men through the threat of sexual violence against women and the Black male rapist myth has been used to sustain mass incarceration, which ultimately reinforces the exploitation of the working class. Black Americans have not been the only demographic who’s marginalization has been justified by myths of sexual violence. The massive waves of immigrants, predominantly non-white Latin Americans, who have presented themselves at the Southern border have become an incredibly politically contentious group. Throughout the span of the 2016 Presidential election, anti-immigrant rhetoric became foundational to the right wing populism that brought Republican nominee Donald Trump to victory. During a particularly infamous campaign speech, Trump referred to migrants traveling across South America and crossing over into the U.S. as “‘rapists’” and that women migrants were being raped at “‘levels nobody’s ever seen before,’” claims that he ultimately could not back with empirical data (Mark 2018). Throughout the 2016-2020 Trump administration, his “Zero Tolerance” immigration policy prosecuted migrants at the border for illegal entry and forcibly separated migrant children from their parents, with some parents even being deported while their children were still detained in the states (Diaz 2021). According to Pew Research Center, ICE arrests rose by over 30% in 2017 after an executive order from then-President Trump expanded their authority to allow for arrests of migrants without criminal records (Gramlich 2020). Thousands of migrants who presented themselves at the border – which is considered a legal way to request asylum by the Department of Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS 2022) – were held in detention centers and treated as criminals while the President justified it all by calling them “rapists.” Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric was one of the main aspects of his right wing populist campaign which ultimately brought him to victory. In the 2016 election, Trump won 67% of white voters without a college degree, one of the largest margins seen by a presidential candidate since 1980 (Maniam 2016). Coincidentally, the 1980s was around the time that neoliberalism became a dominant economic ideology in the United States due to the Reagan administration. Between 1980 and 2000, the U.S. experienced the loss of around 2 million manufacturing jobs (Charles 2019). As individuals without a college degree are more likely to work blue collar jobs and Trump’s campaign was centered around the classic image of immigrants “stealing” jobs from naturalized Americans, it is only logical that non college educated white voters would be so overwhelmingly supportive of his presidential bid. Donald Trump’s decision to paint Latin American migrants as “rapists” conveniently took away from the image of migrants as predominantly people in search of work. His criminalization of migrants and the increase in ICE arrests and detentions ultimately enforced the hegemony of Whiteness and maintained the racial divisions amongst the working masses. Rape myths and public misconceptions of the reality of sexual violence have been the driving force behind the criminalization of Black men and non-white immigrants in the U.S. Mass incarceration and anti-immigrant domestic policy has kept the working class powerless and divided with “protecting” women being used as one of many convenient excuses. The dominance of White, cisgender, heterosexual, wealthy men in the United States is maintained while politicians try to convince the public that freedom of “vulnerable” members of society such as women is their main concern. The reality is that the criminal justice system in the United States does not and has never been concerned with sexual violence against women; the states’ primary concern is and always has been maintaining White Supremacist and capitalist hegemony. Works Cited Bourgois P. (2011). Lumpen Abuse: The Human Cost of Righteous Neoliberalism. City & society (Washington, D.C.), 23(1), 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-744X.2011.01045.x Butler, P., Strode, B., & Johnson, A. (2021, August 23). How atrocious prisons conditions make us all less safe. Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/how-atrocious-prisons-conditions-make-us-all-less-safe Charles, Hurst, E., & Schwartz, M. (2019). The Transformation of Manufacturing and the Decline in US Employment. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 33(1), 307–372. https://doi.org/10.1086/700896 Coates, T.-N. (2013, July 16). How stand your ground relates to George Zimmerman. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/07/how-stand-your-ground-relates-to-george-zimmerman/277829/ Criminal justice fact sheet. NAACP. (2021, May 24). Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://naacp.org/resources/criminal-justice-fact-sheet Diaz, J. (2021, January 27). Justice Department rescinds Trump's 'Zero tolerance' immigration policy. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/01/27/961048895/justice-department-rescinds-trumps-zero-tolerance-immigration-policy Duru. (2004). The Central Park five, the Scottsboro boys and the myth of the bestial black man. Cardozo Law Review, 25(4), 1315–. Franks. (2014). Real men advance, real women retreat: Stand Your Ground, battered women’s syndrome, and violence as male privilege. University of Miami Law Review, 68(4), 1099–. Gill, L., Mellins, S., French, P., & Vaughn, J. (2020, February 4). Judge Denies 'Stand Your Ground' Defense For Alabama Woman Who Killed Her Alleged Rapist. The Appeal. https://theappeal.org/judge-denies-stand-your-ground-defense-for-alabama-woman-who-killed-her-alleged-rapist/. Gramlich, J. (2020, September 8). How border apprehensions, ice arrests and deportations have changed under trump. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/02/how-border-apprehensions-ice-arrests-and-deportations-have-changed-under-trump/ Griffith, K., & Fruen, L. (2020, November 1). Alabama woman pleads guilty to murdering her rapist. Daily Mail Online. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8825697/Alabama-woman-pleads-GUILTY-murdering-rapist.html Mark, M. (2018, April 5). Trump just referred to one of his most infamous campaign comments: Calling Mexicans 'rapists'. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/trump-mexicans-rapists-remark-reference-2018-4 Perpetrators of sexual violence: Statistics. RAINN. (n.d.). https://www.rainn.org/statistics/perpetrators-sexual-violence Pilgrim, D. (2000, November). The brute caricature. Ferris State University. https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/brute/homepage.htm Pérez-peña, R. (2017, January 28). Woman linked to 1955 Emmett till murder tells historian her claims were false. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/27/us/emmett-till-lynching-carolyn-bryant-donham.html Questions and answers: Asylum eligibility and applications. USCIS. (2022, March 15). https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/refugees-and-asylum/asylum/asylum-frequently-asked-questions/questions-and-answers-asylum-eligibility-and-applications Sawyer, W., & Wagner, P. (2022, March 14). Mass incarceration: The whole pie 2022. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2022.html Teigen, A. (2022, February 9). Self defense and "Stand your ground". National Conference of State Legislatures. https://www.ncsl.org/research/civil-and-criminal-justice/self-defense-and-stand-your-ground.aspx Tyson, A., & Maniam, S. (2020, August 14). Behind trump's victory: Divisions by race, Gender, Education. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/11/09/behind-trumps-victory-divisions-by-race-gender-education/ Vachon, T. E., & Wallace, M. (2013). Globalization, Labor Market Transformation, and Union Decline in U.S. Metropolitan Areas. Labor Studies Journal, 38(3), 229–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160449X13511539 Van Dam, A. (2021, September 28). Analysis | Less than 1% of rapes lead to felony convictions. At least 89% of victims face emotional and physical consequences. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2018/10/06/less-than-percent-rapes-lead-felony-convictions-least-percent-victims-face-emotional-physical-consequences/ AuthorMy name is Emely Mendez. I'm a Dominican American student at CUNY John Jay College and I'm soon to graduate with a BA in Law and Society. My interests primarily consist of radicalism in Black, Indigenous, and immigrant communities, gender as an oppressive force, and the neocolonial relationship between the United States and Latin America. Archives July 2022 Jair Bolsonaro rode the right-wing populist wing to power in 2018. Furthermore, he has acted like Hitler when referring to the Indigenous people and other minorities. Bolsonaro has gone as far as to label Brazil's indigenous people as "inferior" and has talked about "wiping them out.” However, his most cruel impulses are reserved for disregarding the Amazon rainforest, because he does not believe in climate change. Indigenous Brazilian tribal leaders have even gone as far as to file two requests with the International Criminal Court (ICC) one for genocide and another for crimes against humanity. Crimes against Humanity charge is because of his deforestation policies, and they genocide refers to his COVID-19 policies. President Emmanuel Macron of France has even threatened international intervention to prevent the destruction. Let us constitute a new rule that you need to be arrested if you are a politician who committed crimes against humanity. The International Criminal Court must issue an arrest warrant; if found guilty by the ICC the authorities in their own countries must follow through on the indictment. There is hope for making this a reality, given that Indigenous Brazilians believe they have enough proof to charge Bolsonaro with both Crimes against Humanity and Genocide. "Our house is on fire," tweeted President Macron in 2018 about his disgust with Bolsonaro for his lack of respect for the Rainforest and environment in general. While Macron's war of words with Bolsonaro may not have helped heal relations between the two leaders, it did inspire the leader of an Indigenous Brazilian tribe. Ninawa is a leader of the Indigenous Brazilian people, "Huni Kui." He wrote a letter to France's president urging him to use his power to stop what he calls the "predation" of his land. Ninawa wants Bolsonaro to completely stop farming, logging, and developmental projects that harm the Amazon. Ninawa came with more than a strongly worded letter; he even had a plan to stop Bolsonaro right in his tracks. Ninawa’s plan involved asking the European leaders to stop facilitating the trade of products linked to deforestation: soybeans, meat, wood. Ninawa has great hope for his plan to work because France is the new leader of the E.U., and Macron is already a sympathizer of his cause. Ninawa is not the only indigenous person trying to be an activist for the environment; two other Brazilian Indigenous women also take the fight head-on. Samela Sateré-Mawé and Sônia Guajajara are two Brazilian indigenous women fighting to stop the destruction of the Rainforest and raise awareness about climate change. Samela is from Manaus, in the Amazon, and Sônia is from Araribóia, in Maranhão. "We Indigenous peoples have been activists long before this word even existed."[1] Samela and Sônia believe that the destruction of their homeland is tragic, but they also believe the far more significant damage lies in the future. They are highly aware of the changing climate and fear that not only will they have to suffer through deforestation, but their children will not even have a place to call home. As indigenous people of the Amazon, they think they should be the leaders of the climate justice movement because it is in their DNA. The perspective of two indigenous women gives a unique set of perspectives because the Rainforest is their home. Samela and Sônia’s work is impressive, it is nothing compared to the impressive work that Eloy Terena has been doing. Eloy Terena is a lawyer for Indigenous people's land rights. Eloy himself is also an indigenous person who hails from the Terena tribe in Brazil. Eloy's village does not offer education past the fourth grade, so it is truly remarkable what he has been able to make of himself. Eloy has been primarily focused on Brazil since Bolsonaro was elected and is the lawyer representing the Indigenous people prosecuting Bolsonaro. Eloy genuinely believes that Indigenous people are essential in the fight to protect the environment and must take action on climate change. "Indigenous territories are the most protected areas and are responsible for environmental balance, for the protection of biodiversity, for the protection of rivers and lakes, and for that reason, these vital spaces are not only for the people who inhabit them but also, above all, for those who live in large urban centers.”[2] While having legal representation is crucial in this fight, actual scientific data is also needed. Scientists and researchers at the "Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) provided such evidence by documenting the varying effects that climate change and deforestation will have on the planet. "Climate change poses additional risks to the stability of the forests. Studies suggest "tipping points" not to be transgressed: 4° C of global warming or 40% of the total deforested area.”[3] Those statistics are even more alarming given that the destruction of the Rainforest has increased significantly over the past fifty years. PNAS argues that we should immediately stop deforestation because reducing deforestation will make the Amazon a global public good for creating high-value products and ecosystem services. If humans do not stop deforestation, PNAS warns that the Amazon will lose it’s biodiversity and cause irreversible damage to the tropical forests. Another concern that PNAS has is that deforestation will also lead to the lengthening of the dry season. The first graph represents what amount of forest area will be left after climate change, and it makes predictions well into the year 2050. The second graph represents the predicted distribution of natural biomes after deforestation. However, an essential part of the article is the two experiments they conducted. One experiment was climate change only, and the other was climate change/deforestation/fire experiments. While PNAS is hopeful that we can do harm-reduction by changing specific policies, they also issued a stark warning. Which alleges that while stopping deforestation will preserve biodiversity and ecosystem services, it will not be enough to stop climate change globally. They recommend every nation needs to follow through on their promises in the Paris Climate Accords and then some. Let 2022 be the beginning of a new era where leaders who cause destruction and suffering in a suit from behind a desk are held just as responsible as the ax murderer walking down the street. The Indigenous tribes of Brazil believe they have enough evidence to prosecute Jair for genocide and crimes against humanity successfully. Eloy said, "we believe there are acts in progress in Brazil that constitute crimes against humanity, genocide, and ecocide.”[4] Along with his environmental policies, Bolsonaro also mismanaged COVID-19 in his country, which hit the indigenous communities the hardest. Approximately 900,000 indigenous people are more susceptible to COVID-19 because of their weaker immune systems, and an estimated 1,166 have passed away. These horrific crimes are being flaunted in the open with no fear of repercussion, and accountability needs to happen. If a nation leader commits a crime, the International Criminal Court must issue an arrest warrant; if found guilty of genocide by the ICC, the authorities in their own countries must follow through on the indictment. [1] James, Chantal. “In Conversation with Two Indigenous Women Fighting for the Future of the Amazon-and the Planet.” Vogue, December 13, 2021. https://www.vogue.com/article/sonia-guajajara-samela-satere-mawe-brazil-amazon-interview. [2] Brazão, Mariana, Lara Bartilotti Picanço, and Natália Tosi. “Interview with Eloy Terena, I ndigenous Land Rights Activist in Brazil.” Wilson Center, August 9, 2021. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/interview-eloy-terena-indigenous-land-rights-activist-brazil. [3] Nobre, Carlos A., Gilvan Sampaio, and Laura S. Borma. “Land-Use and Climate Change Risks in the Amazon and the Need of a Novel Sustainable Development Paradigm.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Accessed April 7, 2022. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27638214/. [4] Aljazeera. “Brazil Indigenous Group Sues Bolsonaro at ICC for 'Genocide'.” Indigenous Rights News | Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera, August 9, 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/8/9/brazil-indigenous-group-sues-bolsonaro-at-icc-for-genocide. Bibliography Brazão, Mariana, Lara Bartilotti Picanço, and Natália Tosi. “Interview with Eloy Terena, Indigenous Land Rights Activist in Brazil.” Wilson Center, August 9, 2021. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/interview-eloy-terena-indigenous-land-rights-activist-brazil. Cetinic, Oleg. “Indigenous Leader to France's Macron: Save the Amazon.” AP NEWS. Associated Press, October 2, 2021. https://apnews.com/article/climate-change-france-paris-forests-emmanuel-macron-d66a05f0ed407b2429fb84e4f349b0f6. James, Chantal. “In Conversation with Two Indigenous Women Fighting for the Future of the Amazon-and the Planet.” Vogue, December 13, 2021. https://www.vogue.com/article/sonia-guajajara-samela-satere-mawe-brazil-amazon-interview. Nobre, Carlos A., Gilvan Sampaio, and Laura S. Borma. “Land-Use and Climate Change Risks in the Amazon and the Need of a Novel Sustainable Development Paradigm.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Accessed April 7, 2022. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27638214/. AuthorDan Sullivan is a senior at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte studying World War 2 History and minoring in Communications and Journalism. When it comes to writing about Marxism and Socialism he takes a concentrated look into the U.S. and E.U. Imperialism especially since the collapse of the Soviet Union. He is very passionate about creating and putting into place a brand new system of eco-socialism to address the ongoing food and climate crisis. He also takes an interest in how the American church perpetuates the ongoing cycle of violence of American Capitalism by keeping workers content with deplorable conditions. He plans on working for a non-corporate media outlet to report on the U.S. Empire and NATO war crimes and imperialism. Archives June 2022 Over the past few years, there has been widespread debate about the validity and morality of (keeping up and tearing down) statues of controversial historical figures. The conservative side of the argument contests that tearing down the statues, no matter when they were erected, is an activity which will surely lead to us forgetting or neglecting our history. When we think of statues of individuals, we know that there is a celebratory characteristic to them, inherent to their statuesque form. We know this because, when we consider erecting a statue of someone, we think of individuals who we believe should be celebrated: civil rights leaders, union activists, philanthropists, and humanists. We associate the construction of statues of historical figures with a celebration of the individual being depicted. No one ever imagines (in our time) erecting a statue of a figure who is disliked; no rational person in the twenty-first century wants to construct a statue of Adolf Hitler or Il Duce. The reason for this immediate rejection of the notion of architecturally institutionalizing these controversial figures of history is that we associate statues themselves with positive figures; at least we do in modern times. The positive connotation of statues of individuals is important for this essay’s later conclusions. One might argue that we do not only erect monuments to historical leaders, but to events as well. Indeed, we have memorials for the World Wars, battles, tragedies, and conflicts all over the world. And yet these monuments do not follow the above criteria that says statues are celebratory. This is because there is a disconnect between the figure and meaning of statues and memorials. We erect statues to commemorate people of great dignity, worthy of respect. We erect memorials to honour (remember) past tragedies. No one could argue that a Holocaust memorial means we are attributing respect to the Holocaust. At the same time, no one would argue that we should erect a statue of Adolf Hitler and claim that it is a Holocaust memorial. But when it comes to the modern debate over whether to keep up or tear down statues of such figures as Robert E. Lee, an American general who fought on the side of the South in the American Civil War (that is, he fought for slavery), people seem to lack the reasoning that says morally bad people should not be commemorated by statues. Whereas it would now be agreed that we should keep the history of fascist Italy under Mussolini confined to history books rather than statues, there lacks that consensus over statues which already exist. This is to say that while no one wants to put up a statue of Mussolini, it seems some reactionaries would have a hard time tearing one down. There is no explanation for the conservative argument other than general lack of critical thinking. At least there is the consensus that more statues of Egerton Ryerson, Robert E. Lee, and their moral peers should not be constructed in our time. The argument persists, though, over whether the existing statues of these people deserve to remain. As mentioned, the conservatives believe that statue-removal is an egregious act because it constitutes the dismantling of history. In reality, however, the removal of these statues constitutes recognition of history; we must be aware of the history of the person whose statue is being taken down in order for there to be a valid consensus for the popular removal of that statue. The lack of historical knowledge only lies in the reactionary conservative minds, who think that these such figures were morally appreciable people who deserve to maintain their statuehood in the twenty-first century, despite the fact that statues are naturally celebratory. Are the proponents of the statue-salvation argument so historically illiterate that they would idolize morally bankrupt, anti-humanist murderers, genociders, and slave-traders? It seems that way. Rather than understanding the contemptibility of some history, conservatives would hold that history remains true only in stone figures which predate us. Rather than read history books, conservatives would like to claim that their historical vindication comes through defending the commemoration of the worst people in history. Conservatives must come to realize that one needs not defend history to be historically aware; rather, one must acknowledge the unbiased truth of history, which leads us to oppose the commemoration of historical antagonists. Perhaps it is time we quit drudging through the arguments of the macabre past, and live in the present, where the ethical values of these figures would earn them dismissal from any moral society. Statue removal does not in any way promote ignorance or apathy toward history. It does promote the teaching of that history by more morally acceptable means, such as in schools and general public educational settings. If these statues remain, our culture remains toxified by the slave-owners and racist lawmakers of the past. Let these statues fall, let the people learn their crimes in the history books, and let new monuments be constructed of those events which should be mourned, and of those people who should be celebrated (not just remembered). AuthorNolan Long is a Canadian undergraduate student in political studies, with a specific interest in Marxist political theory and history. Archives June 2022 Countries in Latin America have often faced the possibility of U.S. intervention, whether it be economic or military. From 1968 to 1989, the governments of Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Bolivia, Paraguay, Brazil, Peru, and Ecuador were overthrown, and they were usually leftist/Marxist governments. After the threat of Fascism was defeated at the end of WWII, two main ideologies competed to be the dominant force in the world. Capitalism and Communism. Latin America proved to be the perfect place for Proxy Wars between the United States and the Soviet Union to square off. At Operation Condor's height, the main perpetrators and advocates were Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon. Kissinger and Nixon were both big believers in the "domino theory," which was a theory during the Cold War that if one country fell to Communism, the rest in the region would fall next. So, to stop the spread, the U.S. and its allies would often work together to overthrow leftist governments and install opposition leaders in Latin America and all over the world. These opposition governments would be pretty brutal and murder thousands of innocent civilians in some cases. However, even today, in the 21st century, long after the Cold War ended, the United States still keeps trying to overthrow governments in Latin America. Two of the most recent cases have been in Venezuela and Bolivia. In 2019, the United States successfully ousted Evo Morales as president. Moreover, in 2020, there was a half-assed attempt to overthrow Maduro in Venezuela by American Mercenaries and exiled Venezuelan nationals. This paper will explore how the United States continues to overthrow these governments and the legality behind such actions. It will also examine how these coups look from the leftist leader's perspective using two documentary films. Hugo Chávez came to power in Venezuela in 1999 and was often regarded as a modern-day Simon Bolivar, but his critics in the U.S. and elsewhere referred to him as "just another thug." Some of Chávez's most notable moments are his frequent criticisms of the state of Israel and calling President George W. Bush "the devil" during his 2006 U.N. speech. Chávez was born in Sabaneta as the youngest of six children. He was born on July 28, 1954, in Sabaneta, Barinas. His mom and dad both had jobs as school teachers and did not have adequate money, so he was sent to live with his Grandma in Barinas, a Venezuelan city. While serving in the Venezuelan army, Hugo became fascinated with leftist philosophers and revolutionaries such as Mao Zedong, Vladamir Lenin, and Karl Marx. However, Hugo took most of his influence from Ezequiel Zamora, a Venezuelan soldier and revolutionary, and he specifically referenced the work "The Times of Ezequiel Zamora." After Hugo was forcibly retired from the military, he began his work in revolutionary politics, eventually leading to a jailed coup attempt in 1992. After his release, he ran for president and was elected in 1999. Chávez's time in office was marked by improving five key institutions:

Chávez was widely admired in Venezuela even after his death from cancer in 2013. Some citizens even have his eyes tattooed on their heads above their eyes. Hugo's rise to power is genuinely fascinating, but Evo's is even better. Evo Morales was elected president of Bolivia in 2006 at the heart of the water privatization crisis. Evo's election was remarkable because he was the country's first Indigenous president after having all the previous presidents be a part of the white minority. After Evo graduated from high school, he, like Chávez, joined the military and eventually moved with his family to eastern Bolivia. He became active in the Bolivian worker unions and eventually became the general secretary of the coca-growers union in 1985. Evo eventually took an interest in politics, founded the leftist nationalist party, and named it “Movement Toward Socialism" (Movimiento al Socialismo M.A.S.). Evo eventually ran for president but lost in 2002. He ran again in 2005 and quickly won with fifty-four percent of the vote. Some of the pledges he made were:

Evo's presidency was also filled with many anti-American sentiments, not just through legislation but through speeches he gave. "Death to the Yankees!" His disdain did not just stop for America but Israel and NATO as well calling them "butchers" and "assassins." While he did have friendly relationships with notable U.S. politicians such as Jimmy Carter and Bernie Sanders, he remained staunchly anti-America. Even recently, he refused to condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine and instead blamed America and NATO for starting the conflict. "A country which has "caused the death of millions with the atomic bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Condor Plan in Latin America and NATO interventionism in so many countries of the world now threatens to make Russia' pay a high price' for defending its continuity as a sovereign state.”[1] Despite both Chávez and Morales being leftist leaders from Latin America, they were also both overthrown in U.S.-backed coups in ordinary as well. Chávez was successfully ousted in 2002 by the Bush administration and Morales in 2019 by the Trump administration. Two documentary films help explain how these leaders reached that point:

"The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" begins with Hugo Chávez walking around Venezuela, giving speeches railing against neoliberalism, and showing how the rest of the International community views him. It then explains how Chávez rose to power and what a typical day for him was like, as well as him doing his infamous TV Show, Alo Presidente, which allows citizens to call in and talk to Chávez. Viewers get to see differing perspectives on how the rich and poor view Chávez. Wealthy Venezuelans hate him and view Chávez as a communist who will destroy the Venezuelan economy because he wants to nationalize the oil industry. Poor Venezuelans, however, love Hugo and always wear these unique red shirts when they go to see him in public. They are referred to as "Chavismos." Western hostility toward Chávez increased significantly after he finally decided to nationalize the oil industry "Petróleos de Venezuela, PDVSA." This decision dramatically angers business leader Pedro Carmona and union boss Carlos Ortega, and they start scheming to overthrow Chávez. They travel to Washington D.C. to meet with C.I.A. and State Department officials. On April 11, 2001, opposition protesters marched on the headquarters of Petróleos while Chávez supporters headed toward the presidential palace. Chaos breaks out, resulting in the death of civilians, and both sides blame each other for the violence. Military generals head to Chávez and demand his resignation as President of Venezuela. Opposition leaders appear on the country's private tv network and tell the people of Venezuela that a new government will be established. Chávez's support by the people axes the new government's story that Chávez resigned from the presidency, and on April 13, figures of the new government were arrested. Chávez returns to the country after regaining military control and tells his people that they can protest against him, but they cannot defy the Constitution. Varying opposition leaders and participants in the coup either fled to the United States or stayed in the country because Hugo said no one would be held accountable. Events leading to Evo Morales's removal from the presidency follow a very similar path, and it is well documented in the movie "It was a Coup." Evo Morales had been accusing the United States of trying to destabilize his government ever since being elected president. He even made a trip to the United States in 2013 to visit Jimmy Carter to help improve relations. Evo always had a rocky relationship with the U.S. Presidents, including Obama, because he thought Obama was pandering and imperialistic. His relationship with Donald Trump was way more tumultuous because of Trump's arrogance and embrace of "American Exceptionalism." When Trump threatened North Korea with "fire and fury," Evo Morales condemned him and said his threats were an insult to humanity. At the 2018 U.N. security council meeting, Morales tore into Trump and American foreign policy. Evo raged that the United States could not care less about human rights or democracy and listed the "failings" of the country. When the 2019 presidential crisis occurred in the country and Morales was ousted as the President, Trump and Elon Musk openly celebrated the news on Twitter. It became apparent immediately that the U.S. Government was involved in the coup. "It was a Coup" opens with the beginning of the 2019 Bolivia election and how the U.S.-backed group "Organization of American States" influenced it. Organization of American States is an international organization created in the late 1940s to help cooperation between America and its Latin American counterparts. "In Nov. 2019, the O.A.S. issued a preliminary report questioning the transparency of the presidential elections when the vote count was still ongoing. Using this report as a pretext, opposition right-wing politicians Carlos Mesa and Fernando Camacho urged for demonstrations, which paramilitary groups and the Police supported." Riots ensued across Bolivia for twenty-one days before the European Union, O.A.S., United States, Bolivian Police, and Bolivian military urged Morales to resign. Opposition to morales is a right-wing racist Christian fascist government called National Unity Front. While a large chunk of the Bolivian population is Indigenous with their religion, forty-one percent, there is a small minority of "racist elite" that is very white and Christian. After the coup was successful, the Interim President, Jeanine Áñez, went to the Balcony of the Presidential Palace and held up a bible, and declared that "God has returned to Bolivia!" Áñez was not the only politician who viewed the coup as having the approval of Jesus himself, the coup leader and billionaire Luis Fernando had a very similar reaction. "With a Bible in one hand and a national flag in the other, Camacho bowed his head in prayer above the presidential seal, fulfilling his vow to purge his country's Native heritage from government and "return God to the burned palace.”[2] The coup mongers in Bolivia felt justified in overthrowing the government because they had Jesus on their side. They were destroying the reign of the evil Indigenous people with their false religion. There were similar tones with the efforts of regime change attempts in Venezuela, not just in 2002 but in 2017 and 2020. Then vice-president Mike Pence said that the United States could not “just stand by and watch the evil Maduro regime destroy one of the most successful countries in our hemisphere.” When Jordan Goudreau's mercenary firm "Silvercorp" organized an attempted coup in 2020, he declared in a social media video that "a brave and noble operation is underway" as they invaded a sovereign nation. American mainstream media constantly portrays the ouster of a leftist leader as an evil dictator being thrown off the power by the American liberators. They never acknowledge the possibility that the replacement government could be even worse or that they will have the possibility to commit human rights violations. Bolivia's interim government at the time did exactly that by Jeanine Áñez committing genocide against the Indigenous protestsers by ordering the military to execute protestors. Evo Morales was crying at the sight of what was happening to his country. "I want to tell you, brothers and sisters, that the fight does not end here; we will continue this fight for equality, for peace,”[3] Morales declared. Venezuelan opposition members were also accused of having fascist and racist tendencies and corruption. Jeanine Áñez's Venezuelan counterpart Juan Guaidó was recently caught up in a corruption scandal that many think undermined him as a legitimate presidential candidate. Specifically, Guaidó, along with other members of his team and various opposition members, were caught in an influence-peddling operation. "The interim government has become a group that has propitiated unacceptable actions of corruption that seriously hurt the democratic struggle and move us away from our goal of freedom.”[4] Essentially, the type of candidates that represent the opposition to the country's current government have many skeletons in their closets. However, it is never taken into account because of the economic and alternative interests of the U.S. government. For Americans to access this information, they usually have to go to alternative sources such as "TheGrayZone," "Redfish media," or leftist media from the country to find this type of information. While it is essential always to remain skeptical because such sources could produce propaganda, it still does not mean that the U.S. or western media, in general, cannot have propaganda of their own. It does not stop with western media producing propaganda either; the government and leaders also play an integral role in such propaganda. When Donald Trump was still president of the United States, he invited Juan Guaidó to the 2020 SOTU, State of the Union. He called Guaidó "the true President of Venezuela," with no actual evidence to back up that claim except unproven allegations of voter fraud in the 2018 Venezuelan election. Guaidó was then given a standing ovation by Republicans and Democrats alike. In the same year, when Bernie Sanders was running for president for the second time, he decided to support Morales during the presidential crisis of 2019 and agreed he was the victim of a coup. He specifically cited the Bolivian opposition's use of the military to secure their power as proof. "Now we can argue about his going for a fourth term, whether that was a wise thing to do... But at the end of the day, the military intervened in that process and asked him to leave. When the military intervenes, Jorge, in my view, that's called a 'coup, said Bernie Sanders.”[5] He was the only politician running in 2020 to call the events in Bolivia a coup, while all the other candidates said that Morales was on his way to becoming a dictator and needed to be forcibly removed. Scholars have researched this topic to see how political unrest in other nations is viewed by the citizens and leaders on the receiving end. Before taking a deeper look, let’s get the perspectives from the mouths of the leaders themselves. During an interview with Vice News in 2020, Morales was asked how he had been doing since the crisis. Moreover, why does he perceives what happened as a coup. First, Evo begins talking about how his term was supposed to end on January 22, 2020, and he was forced to resign on November 11, 2019. Next, Evo talks about how the Police joined with the opposition, and then eventually, the armed forces asked for his resignation. The main reason why Evo decided to resign was to avoid mass murder on a large scale because of how the citizens were in mutiny. The interim government's massacre incredibly saddened Morales; 35 protesters were murdered, but he knew deep down that democracy would return to Bolivia, and his legacy could never be erased. However, Morales also saw a bright spot in the situation by claiming that his party would win over the younger generations after the coup. "For the younger generations, it is important to know what it is like to live under a right-wing government, under a dictatorship.”[6] Chávez had a very similar reaction to the coup attempt against him. Before the coup attempt against Chávez, there was zero possibility of U.S. involvement because he thought the era of Cold War power politics had ended. However, after the coup was over and Chávez had successfully returned to power, he changed his tune and accused the U.S. of orchestrating it themselves. He even alleged that U.S. military personnel met with top Venezuelan coup leaders. While there was still no way to prove that the U.S. was involved with the coup at the time, evidence eventually emerged that the U.S. had prior knowledge of the coup. While giving no direct support to the opposition, they would have no problem seeing Chávez ousted. While these coups took place in separate countries, they both have a similar story about how they happened. Allegations of corruption or voter fraud appear, and the current government is portrayed as a budding dictatorship, so a coup is needed to save democracy. While it is essential to keep in mind that leftist authoritarian leaders have existed in the past and currently as well who are more than capable of human rights violations, it still does not excuse the actions of imperialist governments. So how does one know how to tell if a tyrant is trying to steal an election or if it is simply more lies from the U.S. State Department? Doctor Greogry Wilpert has an interesting analysis about how the U.S. did want Chávez ousted from power and got away with lying about their involvement. Gregory Wilpert is a doctor in sociology who is a staunch supporter of the Bolivarian Revolution. However, he did move to Caracas with his family to help outsiders get a better understanding of the current events in Venezuela. After Chávez died, he appeared on the independent American T.V. show "Democracy Now!" before moving to Ecuador to work for another T.V. channel. Before all that happened, though, he wrote a fascinating article regarding the 2002 coup attempt. "The first, most widely accepted version has it that Chávez was arrested by opposition-allied military officers on the pretense that he ordered the attack on the demonstrators; the coup plotters then proceeded to dismantle all state institutions in order to establish a dictatorship. The second version, told by the hardcore opposition, holds that there was no coup. In this telling, Chávez did order the Venezuelan military, as well as Chavista paramilitary thugs, to shoot the demonstrators.”[7] Wilpert later discusses how given that the two sides of the story are so vastly different, it is vital not to take any side too seriously. He later comments on how crucial it is to be incredibly skeptical of the U.S. because of Venezuela's large abundance of natural resources and the U.S. Government's long history of intervening in foreign relations for ulterior motives. Wilpert then mentions a book called "The Silence and the Scorpion" written by scholar and teacher Brian Nelson, who tries to give an accurate account of the coup. Wilpert criticizes the book as being an apologist for the opposition because the people he chose to interview for the book were four opposition marchers, three pro-Chávez demonstrators, three journalists, four politicians, and five military generals. However, most of the book is taken up from the perspective of three people Efraín Vásquez Velasco and Manuel Rosendo, Francisco Usón. All three of these men are against Chávez and his regime, which Wilpert points out delegitimizes the book as a non-bias source. "Moreover, he leaves it unclear as to whether the book is meant as an objective description or merely a narrative version of his informants' interviews. One is tempted to think the latter since he never corrects their outright falsehoods, such as Vásquez Velasco's claim that Chávez "had always dreamed of a socialist Venezuela.”[8] Chávez did not even begin talking about socialism in Venezuela until 2005. While the research and analysis that Wilpert makes are thought-provoking, a criticism that could be lodged at him is the same he lodged at Nelson. Which is that Nelson was pro-Chávez and that he could not give an accurate account of the events that occurred in 2002. Another fascinating article further indicated the U.S.’s involvement and was regarded as one of the most censored documents between 2002-2003. The article was written by an American journalist named Karen Talbot titled "Coup-Making in Venezuela: Bush and the Oil Factors," written in July 2002. Talbot is not only a journalist but the director of the "International Council for Peace and Justice." Talbot begins talking about how Hugo Chávez saw himself as a Robinhood-like figure who stole from the rich and gave to the poor. It made him incredibly unpopular with wealthy elitists in his country and the United States. Next, she discusses how while the details of the coup against Chávez still need to be found, the evidence of the Bush administration's involvement has already come to light. Talbot uses two pieces of information about how prominent Washington and Bush's administration officials constantly criticized Chávez, and the administration failed to condemn the coup against Chávez. For example, Condoleezza Rice famously said, "I believe there is an assault on democracy in Venezuela, and I believe that there are significant human rights issues in Venezuela," Rice told lawmakers at a congressional hearing. "I believe there is an assault on democracy in Venezuela, and I believe that there are significant human rights issues in Venezuela.”[9] Other examples include:

Nevertheless, probably the most important was since the Bush administration had the support of a large swath of right-wing Cubans. Who not only demanded that Bush do everything in his power to end the regime of Fidel Castro, but due to Chávez's close relationship with Fidel, they demanded he goes as well. Serious opposition to Chávez started when he wanted to nationalize the oil industry, and the opposition had opposite plans to privatize the oil industry. The New York Times reported that one of the top oil executives met with coup leaders at the military coup leader’s headquarters. Bush's Latin American Secretary of State Otto Reich was a right-wing Cuban who was also a lobbyist for Mobil Oil and hosted the Venezuelan coup leaders at the White House. They discussed details about the coup, including when it would happen and its chances of succeeding. The London newspaper "The Guardian" also confirmed that U.S. military personnel decided to meet with the Venezuelan coup leaders in June 2001. U.S. navy personnel even decided to get directly involved in the coup by providing signals intelligence and communications jamming support to Venezuelan military personnel involved. "Seeing the disturbing similarities to the 1973 U.S. instigated Chilean coup-which occurred after one failed coup attempt- the majority of Venezuelan people are remaining vigilant about further moves to oust Chávez. The people of the United States have the responsibility and the possibility to put an end to the Bush administration's anti-democratic overt operations and military interventions in Venezuela.”[10] While the unrest that swept the nation of Venezuela is remarkable, it was not as stunning as the events in Bolivia due to the Brazen nature of the actors involved. "In July 2020, following the Bolivian coup d'etat, Elon Musk tweeted to his more than 40 million followers, "We will coup whoever we want! Deal with it." He made this threat in response to a Twitter user's accusation that the tech billionaire collaborated with the U.S. government to orchestrate a coup against then-Bolivian president Evo Morales as a means to gain greater access to the country's lithium supply after he canceled a contract to privatize Bolivia's lithium mines.”[11] Elon openly bragged about his company's involvement in the coup and that he feels entitled to overthrow governments to get natural resources. After Evo Morales returned from exile in Argentina, he read Elon's tweet out loud to a crowd of his supporters. "He was arrogant so as to carry out coups all for natural resources, all for lithium.”[12] Gabriel Hetland wrote a very in-depth analysis about what he felt led to Morales's ouster in his academic journal of NACLA, North American Congress on Latin America. Gabriel begins talking about how to understand why the country's first indigenous president, who was able to achieve so much with social programs, infrastructure, and indigenous rights, had his career ended so abruptly. In order to help explain how these events unfolded, Hetland went back to all of them in 2016. In 2016, Morales decided to amend the constitution to have indefinite presidential elections, but it failed. Morales and his supporters wanted these indefinite elections because they felt that there would be a "dirty war" campaign against him. Their fears turned out to be legitimate because before Morales tried to amend the constitution, Bolivian conservative media ran a story about Evo having a love child. The evidence that conservative media used to explain their story was that the baby either died or never existed. Nonetheless, it had an impact because Evo lost the vote. He was successful in 2017 with the referendum and was able to run for president again, but it made him unpopular with the middle class. Hetland then further explains that after the Organization of American States (OAS) published the election fraud report after the election fraud report, it caused many people to take to the streets and demand that Morales resign and for a new election. However, it was not until the "Economic and Policy Research" published a report of their own that alleged the OAS was not being truthful. "A report by the Center for Economic and Policy Research makes a convincing case that the OAS acted in a biased manner and failed to present evidence of actual fraud.”[13] While Hetland acknowledges that the OAS acted in bad faith, he also makes some concessions that Morales had not been as popular as he was when he first came to power. Specifically, Hetland mentions an event that occurred in 2011 which pitted Morales against the very indigenous communities he was supposed to be representing as a presiden. Morales wanted to build a road through Bolivia's TIPNIS national park. This event was significant for two main reasons, the first being it showed his counterparts on the left were criticizing Morales. With not only the Indigenous people criticizing him but even one of his former UN Ambassadors, Pablo Solón. Secondly, the TIPNIS conflict caused a split among and even within popular-sector organizations that had previously been allied with Morales. "This led to a weakening of popular-class organizational and mobilizational capacity, a factor some analysts suggest explains the relative slowness with which some social movements came to Morales' defense after the November 10 coup.”[14] Hetland then reassures the readers that this leftist opposition to Morales does not mean the events that unfolded were a coup because the military were still the ones to demand the resignation of Morales. Hetland then describes how the interim government is a quasi- dictatorship. Hetland begins by talking about the various human rights violations that the Áñez government has committed: