|

11/29/2021 V. I. Lenin - Materialism & Empirio-Criticism. Commentary and Analysis (6/23). By: Thomas RigginsRead NowChapter One Section Four: "Did Nature Exist Prior to Man?"This seems to be a big problem for Empirio-criticism. Lenin will look at the views of Avenarius and his two followers R. Willy and J. Petzoldt (1862-1929) and see how this question is dealt with by two of the Russian "Marxist" Machists, V. Bazarov (1874-1939) and N. Valentinov (1880-1964). Avenarius, as we know, has a two term co-ordination; Man-Nature, (with Man as the central term) to explain how we gain knowledge of the contents of the world. Since natural science clearly states that the earth existed before humans it would seem impossible to take the world's contents to be "complexes of sensations." Avenarius therefore introduces the notion of the "potential" into his philosophy. When there are no actual humans there are "potential" humans to sense the complexes of sensations by which reality presents itself. Avenarius talks about embryonic humans-- they are not fully human but also not equal to zero. So also, before any actual humans there are "integral parts of the environment" that have the capacity to become human, etc. So we have a saving co-ordination of Potential(Man)-Nature. On the face of it this is a completely preposterous solution. "No man at all educated or sound-minded," Lenin says, "doubts that the earth existed at a time when there could not have been any life on it, any sensation or any 'central term', and consequently the whole theory of Mach and Avenarius, from which it follows that the earth is a complex of sensations ('bodies are complexes of sensations') or 'complexes of elements in which the psychical and physical are identical', or a 'counter-term of which the central term can never be equal to zero', is philosophical obscurantism, the carrying of subjective idealism to absurdity." Petzoldt, Lenin remarks, realized that Avenarius' position was ridiculous and decided to improve upon it. It is true that we can think about areas without or before there were human beings, he says, but "The epistemologically important question, however," Petzoldt writes, "is not whether we can think of such a region at all, but whether we are entitled to think of it as existing, or as having existed, independently of any individual mind." We shall see that Petzoldt's attempt to improve on Avenarius is not any better than the original. Avenarius puts too much weight on the human self, whether actual or potential according to Petzoldt, whereas, "The only thing," he says, "the theory of knowledge should demand of any conceptions of that which is remote in space or time is that it be conceivable and can be uniquely determined; all the rest is a matter for the special sciences." The expression "uniquely determined" is just Petzoldt's way of saying "the law of causality" according to Lenin. Petzoldt knows that natural science maintains the existence of the earth before humans and he also knows that Avenarius' lack "of the objective factor" in his philosophy puts it at odds with science and this has forced him "to resort to causality (unique determination). The earth existed, for its existence prior to man is causally connected with the present existence of the earth." Petzoldt's "solution" actually wipes out the "complexes of sensations" hypothesis regarding the nature of the external world and he "only entangled himself still more, for only one solution is possible, viz., the recognition that the external world reflected by our mind exists independently of our mind." Our old friend, the hapless R. Willy, is the next to try and save the "complexes of sensations." What could be experiencing the earth before there were humans? Well, he says, "we must simply regard the animal kingdom --- be it the most insignificant worm --- as primitive fellow-men if we regard animal life only in connection with general experience." So now a primitive worm is the stand in for human consciousness in the "principle co-ordination." Besides being a ludicrous theory it fails to solve the main issue because the earth existed before there were any primitive worms as well. The empirio-criticists should, I think, just have appealed to Berkeley because his concept of God would have solved their problems. Willy came up with his worm argument in 1896, but he eventually abandoned it and returned to the fray in 1905 with a new solution to the problem. Forget about the so-called millions of years before man came into existence. Time too is a product of the complexes of sensations. This means, he goes on to say, "that things outside men are only impressions, bits of fantasy fabricated by men with the help of a few fragments we find around us ['fragments' of what?]. And why not? Need the philosopher fear the stream of life?" Well, the answer to that is NO! I hope my fellow philosophers will all agree to that! But we cannot follow Willy to his carpe diem conclusion! "And so I say to myself: abandon all erudite system-making and grasp the moment [seize the day] the moment you are living in, the moment which alone brings happiness." Lenin is unimpressed. Rather than be forced by their own logic into a materialist acceptance of the objectivity of the world, the empirio-criticists scurry off into a solipsistic world of their own making. So much for them. Lenin now wants to see how the home grown "Marxist"- Machists in Russia handle this problem. He will first discuss A. Bazarov, real name V.A. Rudnev, 1874-1939. Bazarov joined the party in 1896, was a Bolshevik from 1904 to 1907 and was a Menshevik from 1917 until 1919. After 1921 he was employed by the Soviet government as a planner. His demise in 1939 raised my suspicions, but he seems to have died naturally from what I could gather from The Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Lenin is criticizing Bazarov's book Studies 'in' the Philosophy of Marxism. One of the main objections Lenin has to this book is that it treats Plekhanov (1856-1918, The Father of Russian Marxism) as the only representative of Materialism and ignores Marx and Engels! The work that Bazarov attacks is Plekhanov's Notes to Engels 'Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy' (1892). In that work Plekhanov has a passage in which he asks the Idealists what was the world like in the period before there were humans, a period such as the Mesozoic era. Plekhanov is addressing himself to Kantians but his remarks are just as, if not more, applicable to Empirio-monism (the Russian version of Machism) as represented by Bogdanov and Bazarov. In that remote period Plekhanov asks if it was the ichthyosauruses and the archaeopteryxes who were responsible for contemplating the world order? Idealism cannot answer this question hence it must be rejected as contrary to modern science. This burns up Bazarov and he jumps all over Plekhanov saying that even he, Plekhanov, cannot know what "things-in-themselves" are like. We only know how they act on our senses and he quotes Plekhanov: "Apart from this action [on the senses] they possess no aspect." Therefore whatever Plekhanov had to say about ichthyosauruses and archaeopteryxes in attacking the Kantians applies equally to him. Well, if Plekhanov burned up Bazarov, Bazarov has succeeded in burning up Lenin who proceeds to jump on him in turn. Lenin asks Bazarov if he is just taking cheap shots at Plekhanov ( having "a fencing bout " with him ) or is he actually trying to explain materialism. If he thought Plekhanov was wrong he should have explained the correct materialist position, but perhaps Bazarov is himself ignorant of the correct materialist teaching. "If Bazarov," Lenin says, "does not know that the fundamental premise of materialism is the recognition of the external world, of the existence of things outside and independent of our mind, this is a truly striking case of crass ignorance." Well, Bazarov may be confused. Lenin is correct to say the existence of the external world "independent of our mind" is fundamental to materialism— but it is also compatible with objective idealism, as Lenin had earlier remarked himself when referring to Hegel back in Section 3: "Hegel's absolute idealism is reconcilable with the existence of the earth, nature, and the physical universe without man, since nature is regarded as the 'other being' of the absolute idea." Unfortunately, Lenin makes a big mistake when he says here that Berkeley "rebuked the materialists for their recognition of 'objects in themselves' existing independently of our mind and reflected by our mind." Berkeley did rebuke materialists but not for believing that things exist independently from the human mind. The external world has an independent existence from human beings as the idea of God-- analogous to Hegel's other being of the Absolute Idea. Berkeley is thus an absolute (or objective) idealist. Except for the mislabeling of Berkeley, Lenin's argument is essentially correct. Bazarov's fulminations against Plekhanov are off target. As for Valentinov, who supports Bazarov, we can ignore this gentleman as Lenin, in a brief paragraph, shows that his position is "an incoherent jumble of words." Next Up: Chapter One Section FIVE: “DOES MAN THINK WITH THE HELP OF THE BRAIN?” AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association.

0 Comments

11/26/2021 V. I. Lenin - Materialism & Empirio-Criticism. Commentary and Analysis (5/23). By: Thomas RigginsRead NowChapter One Section Three: The Principal Co-Ordination and "Naive Realism"Lenin now turns to two works by Avenarius, The Human Concept of the World and the Notes. He will give us the essence of the doctrine of the "Principle Co-Ordination" and its relation to our everyday notions of naive realism. Avenarius' thesis is that of, in his own words, "the indissoluble co-ordination of the self and the environment.” The self and the environment are always together, like a horse and carriage or love and marriage! The self is the central term and the environment is the counter term of this co-ordination. Avenarius thinks this doctrine leaves the belief in naive realism untouched, and Mach (Analysis of Sensations) thinks so as well. Lenin thinks this is nuts. In fact, he claims this view, which supposedly co-ordinates naive realism with the self (consciousness), is just warmed over Fichte. Lenin means Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814, 'The Father of German Nationalism'-- a dubious honor), an Idealist who wrote in 1801 that you should "Take care, therefore, not to jump out of yourself and to apprehend anything otherwise than you are able to apprehend it, as consciousness and the thing, as the thing and consciousness; or more precisely, neither the one nor the other, but that which only subsequently becomes resolved into the two, that which is the absolute subjective-objective and objective-subjective." The so-called newest philosophy was just a rehash, a century later, of early German Idealism. Now, what has this empirio-critical doctrine have to do with naive realism? According to Lenin, the naive realism (of "any healthy person") is "the view that things, the environment, the world, exist independently of our sensation, of our consciousness, of our self and of man in general." Not only does the world have an independent existence, human beings have knowledge about it because it interacts with our nervous system, also a part of the world, and reproduces images of itself of which we are conscious-- human consciousness being a higher order property of the organization of matter. "Materialism." Lenin says, “Deliberately makes the 'naive’ belief of mankind the foundation of its theory of knowledge." Lenin takes great pains to stress that this is not just the partisan view of diamat that he is pushing, but it is the standpoint of modern natural science and of scientists in general, even those who would not consider themselves followers of diamat. (Dialectical Materialism) As evidence for this view he turns to Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920) 'The Father of Modern Psychology ' along with William James (1842-1910) who maintained the view that any given reality cannot be described without a reference to the "self" (Avenarius and company) is, in his words, "a false confusion of the content of real experience with reflections about it." Lenin also bolsters his argument by quoting from a 1906 article in Mind, still the leading English philosophy journal, by Norman Kemp Smith (1872-1958, best known for his translation of Kant's Critique of Pure Reason-- for many years the gold standard). After discussing Avenarius' theory of the principle co-ordination of the world of sense experience and the natural world of naive realism viewed as one of complexes of sensations, Smith concludes that Avenarius has failed completely to capture the meaning of naive realism as it is understood by realists [materialists]. Avenarius, Smith writes, "argues that thought is as genuine a form of experience as sense-perception, and so in the end falls back on the time-worn argument of subjective idealism, that thought and reality are inseparable, because reality can only be conceived in thought, and thought involves the presence of the thinker. Not, therefore, any original and profound reestablishment of realism, but only the restatement in its crudest form of the familiar position of subjective idealism is the final outcome of Avenarius' positive speculations." Lenin has pretty much made his main point in this section, which I will reiterate in a moment. He gives a few more examples of how mixed up Avenarius' views are (from W. Schuppe (1836-1913) and O. Ewald-- both of whom will be dealt with in later sections). He again says "it is important to note" that all attempts to combine materialism (realism) and subjective idealism a la Mach and Avenarius into some transcendental philosophy that includes them both is IN FACT an "empty, pseudo-scientific claim." Lenin says that "To build a theory of knowledge on the postulate of the indissoluble connection between the object and human sensation ('complexes of sensations' as identical with bodies; 'world-elements' that are identical both psychically and physically; Avenarius' co-ordination and so forth) is to land inevitably into idealism." And finally, to end this section, Lenin turns to R. Willy (1855-1918), the disciple of Avenarius, who has to admit that the attempt of his master to reconcile empirio-criticism and naive realism is a failure. Willy says you have to take the belief that Avenarius actually subscribed to naive realism "cum grano salis.”* Willy writes, "As a dogma, naive realism would be nothing but the belief in things-in-themselves existing outside man in their perceptible form." Willy thinks that is ridiculous, and perhaps it is in the way he formulated it. I mean, "in their perceptible form" is loaded-- there is an X out there but is that X 100% equal to how our senses perceive it? At any rate, Willy is forced to concede that Avenarius' book, The Human Concept of the World is one that "entirely bears the character of a reconciliation between the naive realism of common sense and the epistemological idealism of school philosophy. But that such a reconciliation could restore the unity and integrity of [basic] experience I would not assert." QED. Next we will go over Section 4 of Chapter One, "Did Nature Exist Prior to Man?" Believe it or not this is still a big issue, whether Nature only existed for 5 days prior to man, ex-president George W. Bush isn’t sure about this! -- a Yale graduate! *cum grano saltis = with a grain of salt. The phrase comes from Pliny the Elder's (24-79 A.D.) Naturalis Historia, regarding the discovery of a recipe for an antidote to a poison. In the antidote, one of the ingredients was a grain of salt. Threats involving the poison were thus to be taken "with a grain of salt" and therefore less seriously.-- Wikipedia AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. 11/24/2021 V. I. Lenin - Materialism & Empirio-Criticism. Commentary and Analysis (4/23). By: Thomas RigginsRead NowChapter One Section Two "The Discovery of the World Elements"What are the "world elements" that Mach has supposedly discovered? In his Mechanics(1883) he wrote, "All natural science can only picture and represent complexes of those elements which we ordinarily call sensations.” Lenin says Mach is confused, because in The Analysis of Sensations he says, "A colour is a physical object when we consider its dependence, for instance, upon the source of illumination (other colours, temperatures, spaces and so forth). When we, however, consider its dependence upon the retina ... it is a psychological object, a sensation.” Here it seems physical and psychological objects are dissimilar. Lenin calls Mach's view an "incoherent jumble." It seems that Mach wants it both ways, but by having two sorts of objects, physical and a sensation, Mach has slipped into materialism despite his claim that there are only sensations and their complexes. This is the viewpoint of natural science and materialism: "matter acting upon our sense-organs produces sensation." The empirio-criticists seem either unaware of their problem here, or just confused. Lenin quotes one of the most important followers of Mach and Avenarius, Joseph Petzoldt [ Ludwig Wittgenstein's teacher ] who wrote that "In the statement that 'sensations are the elements of the world' one must guard against taking the term 'sensation' as denoting something only subjective and therefore ethereal, transforming the ordinary picture of the world into an illusion." This is really muddled and Lenin says he can't help "harping" about it. He tells the empirio-criticists that they must give up their world elements and "simply say that colour is the result of the action of a physical object on the retina, which is the same as saying that sensation is a result of the action of matter on our sense organs." Lenin points out that in fact, as Mach and Avenarius grew older they began to modify their beliefs and materialist elements, as it were, forced themselves upon them. Here is the strong Machian position from Analysis of Sensations -- " It is not bodies that produce sensations, but complexes of elements (complexes of sensations) that make up bodies." But this view is somewhat modified. Avenarius, according to his disciple Rudolf Willy, ended up also accepting some form of "naive realism"-- i.e., the stance of regular people that there are real existing things outside our minds. And his biographer, Oskar Ewald, conceded that he ended with a contradictory system with "idealist" and "realist" positions. [NOTE: Academic philosophy generally prefers the word "realist". Lenin uses "materialist" in deference to Marx and Engels because he thinks it is more honest.] Back to Bogdanov bashing: Bogdanov says he is not a Machian. He only took one thing from Mach. Yes, but what he took, Lenin says "is the basic error of Machism." And what is this basic error, the source of Bogdanov's "philosophical misadventures"? It is that "the external world, matter" is thought to be "identical with sensations." Not only does he assert this, but he reproduces the equivocations and confusions of Avenarius et al when he writes in Empirio-monism that "insofar as the data of experience appear in dependence upon the state of a particular nervous system they form the psychical state of that particular person; insofar as the data of experience are taken outside of such a dependence, we have before us the physical world.” I would like to insert here a note on the use of the term "metaphysics." In the period under discussion this was a term of abuse. Marxists referred to two groups as "metaphysicians"-- the idealists and the mechanical [i.e., non-dialectical] materialists. Dialectical Materialism (Diamat) was a "science." On the other hand idealists and agnostics (those neutral on the realism antirealism issue) called all the materialists "metaphysicians" for, as Lenin puts it, "it seems to them that to recognise the existence of an external world independent of the human mind is to transcend the bounds of experience." Lenin will deal with this later in his book. For the present I think the main point of this section was to show that "What appeared to Bogdanov to be truth is, as a matter of fact, confusion, a wavering between materialism and idealism." This is due to the fact that "the amendment made by Mach and Avenarius to their original idealism amounts to making partial concessions to materialism." Next up (Friday) we will deal with Section Three of Chapter One: "The Principal Co-ordination and 'Naive Realism." AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. 11/22/2021 V. I. Lenin - Materialism & Empirio-Criticism. Commentary and Analysis (3/23). By: Thomas RigginsRead NowChapter One "The Theory of Knowledge of Empirio-Criticism and of Dialectical Materialism Section One "Sensation and Complexes of Sensations"Lenin begins by stating the basic idea of the theory of knowledge (epistemology) of the two bêtes noires of empirio-criticism Ernst Mach and Richard Avenarius. This idea is, that what we experience when we experience "the external world" is what goes on in our own brain-- id est, the "elements" making up the "external world" are actually INTERNAL complexes of sensations. Lenin says, "Mach explicitly states... that things or bodies are complexes of sensations, and that he quite clearly sets up his own philosophical point of view against the opposite theory which holds that sensations are "symbols" of things (it would be more accurate to say images or reflections of things). The latter theory is ”philosophical materialism.” Lenin bases his view on that of Engel's in his work Anti-Dühring. Engel's uses the term Gedanken-Abbilder which Lenin translates as "mental images" or "mental pictures." "Picture" in German, however is das Bild (which can also mean "image") and since Engel's didn't use the term Gedanken-Bilder, I will not use "picture" but "image" (das Abbilder). Engels believes that really existing external things produce "thought-images" in the human brain. I like the German word used for the English "brainwave"-- i.e., der Gedankenblitz, pl., die Gedankenblitzen, literally "thought-wave, waves." So the question, as I see it, is what is the relation of our Gedankenblitzen to the real world when we experience what we take to be an external world. Are they the reflections of external reality, or is external reality simply deduced and constructed out of the Gedankenblitzen? Lenin says, "Anybody who reads Anti-Duhring and Ludwig Feuerbach with the slightest care will find scores of instances when Engels speaks of things and their reflections in the human brain, in our consciousness, thought, etc. Engels does not say that sensations or ideas are 'symbols' of things, for consistent materialism must here use 'image', picture, or reflection instead of 'symbol', as we shall show in detail in the proper place." Well, we shall see. At this point, anyway, it would appear I could be a "consistent" materialist as long as I held that my Gedankenblitzen symbols were produced by actually existing external objects independent of the human brain. We will reconsider this when we get to the "proper place." Lenin says that Mach goes on to explain that we have experiences of certain complexes of sensation that are so intense and consistent that we have become "habituated" (Mach must have gotten this term from Hume) to ascribe the origin of these experiences to an external reality. For Mach, this particular thought wave is no proof of an actually existing external world. We are not justified in going beyond the reality of our own sensations. Remember Diderot and his piano from earlier? Lenin says that he represents "the real views of materialists." Which "views do not consist in deriving sensations from the movement of matter or in reducing sensations to the movement of matter, but in recognising sensation as one of the properties of matter in motion. On this question Engels shared the standpoint of Diderot." This is not clear to me. If sensation is a property of "matter in motion" have we not reduced sensations to the "movement of matter"? Perhaps this will become clearer later. Lenin now switches his attention from Mach to Richard Avenarius (1843 to 1896). His works appear to be out of print in English (if they were ever translated). [Trivia: his mother was Cacile Wagner, Richard Wagner's little sister.] Lenin quickly establishes Avenarius' idealist credentials with a quote from his Prolegomena zu einer Kritik der reinen Erfahrung (Prolegomena to a Critique of Pure Experience): "We have recognised that the existing [thing] is substance endowed with sensation; substance falls away, sensation remains; we must then regard the existing as sensation, at the basis of which there is nothing which does not possess sensation." This is animism! The reason "substance" falls away is that we don't need it to explain the world. All we know is what we experience-- i.e., sensation. Avenarius coined the term "empirio-criticism" to describe his philosophy and his thought was the major influence on Mach. Bogdanov (1873-1928) makes his first appearance in this section. A. A. Bogdanov was the nom de guerre of A.A. Malinovski. who at one time was the #2 Bolshevik after Lenin and a leader of the discredited Proletkul't movement after the revolution. He was an MD who founded the first blood transfusion and research institute in Russia. It is now called The Bogdanov Institute. He lost a power struggle with Lenin (the book we are studying was written to discredit him in the eyes of Bolsheviks) and turned to research. He used his institute to do blood experiments trying to halt aging and reverse the aging process. In fact, when Lenin died his brain was given to Bogdanov to study as well as his body to see if it could be reanimated. It couldn't. Bogdanov accidentally killed himself while doing a blood transfer experiment on himself. There is an interesting article about him on Wikipedia and in Volume 3 of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia. He was a very interesting character who deserves to be better known. Under the influence of Wilhelm Ostwald (a psychologist) as well as Mach and Avenarius, Bogdanov tried to update Marxist materialism by blending it with the thought of empirio-criticism. The result was his book Empirio-monism which is the object of Lenin's ire. It is however only mentioned in passing in this section. In fact Lenin even likes the quote from Empirio-monism that he reproduces here because the Machist Bogdanov ("from forgetfulness") formulates his new position using words that actually describe a materialist outlook, which is that sensation is "the direct connection between consciousness and the external world." This gives Lenin the opportunity to set forth what he thinks is the major fallacy of Idealism. "The sophism of idealist philosophy," he says, "consists in the fact that it regards sensation as being not the connection between consciousness and the external world, but a fence, a wall, separating consciousness from the external world-- not an image of the external phenomenon corresponding to the sensation, but as the 'sole entity.'" This is, I think, the MAIN POINT of this section. Lenin ends this section with some remarks on three other Machians whose Idealism he is going to deal with: the English philosopher Karl Pearson [1857-1936, better known as the founder of mathematical statistics], and the physicists Pierre Duhem [1861-1916] and Henri Poincare [1854-1912]. Next we will go over section 2 of Chapter One: "The Discovery of the World-Elements" AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. 11/19/2021 V. I. Lenin - Materialism & Empirio-Criticism. Commentary and Analysis (2/23). By: Thomas RigginsRead Now"In Lieu of an Introduction" It really is an introduction, about sixteen pages in which Lenin compares the so-called Marxists he is about to criticize to Bishop George Berkeley who is, wrongly I think, considered by many to have been a subjective idealist-- i.e., someone who thinks the existence of "external" objects is dependent on the human mind. Lenin says, for example, "Denying the 'absolute' existence of objects, that is the existence of things outside human knowledge, Berkeley bluntly defines the view point of his opponents as being that they recognise the 'thing-in-itself.'" This is an unfortunate sentence, using as it does both Kantian terminology eighty years in advance of its creation and substituting the term "human knowledge" for Berkeley's term "mind." A few pages later, Lenin corrects himself with a more nuanced view of Berkeley's position. "Deriving 'ideas' from the action of a deity upon the human mind, Berkeley thus approaches objective idealism: the world proves to be not my idea but the product of a single supreme spiritual cause that creates both the 'laws of nature' and the laws distinguishing 'more real' ideas from less real, and so forth." Actually, Berkeley is an objective idealist as he holds that the objects that we see existing in the world truly have an independent existence from human beings and the world could be just as it is even if there were no humans in existence. Lenin also believes this. What differentiates them is Berkeley has an extra entity which Lenin does not have-- i.e., a spiritual being "God" in whose Mind everything exists. Except for this, Lenin and Berkeley have pretty much the same world view (minus dialectics) when it comes to the "real" existence of the external world. Anyone who doubts this need only read "Three Dialogues Between Hylas and Philonous" [1713]. In his desire to smash his contemporary philosophical opponents, Lenin has come near to not giving Berkeley his due. He is much more sophisticated than the people Lenin is opposing. Berkeley's philosophy of "to be is to be perceived" (esse est percipi) is wrongly thought to require that if p exists, then some human consciousness must be perceiving p. This is nicely expressed by Ronald Knox (1888-1957, Cf. Wikipedia) There was a young man who said, "God Must think it exceedingly odd If he finds that this tree Continues to be When there's no one about in the Quad." REPLY Dear Sir: Your astonishment's odd: I am always about in the Quad. And that's why the tree Will continue to be, Since observed by Yours faithfully, GOD. Better is Lenin's interpretation of the views of Hume and Diderot. His reading of Hume is filtered through Thomas Huxley (Darwin's bulldog -- a nickname due to his spirited defense of Darwin) and his 1879 book Hume from which he quotes: "'Realism and idealism are equally probable hypotheses' (i.e., for Hume). Hume does not go beyond sensations. 'Thus the colours red and blue, and the odour of a rose, are simple impressions.... A red rose gives us a complex impression, capable of resolution into the simple impressions of red colour, rose-scent, and numerous others.' Hume admits both the 'materialist position' and the 'idealist position;' the 'collection of perceptions' may be generated by the Fichtean 'ego’[all that is is the Ego-tr] or may be a 'signification' and even a 'symbol' of a 'real something.' This is how Huxley interprets Hume." This is more or less how Hume is still interpreted and he is also still very popular in English speaking philosophical fora and lurks in the background of modern bourgeois philosophical "materialism" and "realism." In the same generation as Hume, Lenin appreciates the materialism of the French philosopher Diderot, and puts forth (in passing which I have capitalized) an important principle in the following quote. "And Diderot, who came very close to the standpoint of contemporary materialism (THAT ARGUMENTS AND SYLLOGISMS ALONE DO NOT SUFFICE TO REFUTE IDEALISM, AND HERE IT IS NOT A QUESTION FOR THEORETICAL ARGUMENT) notes the similarity of the premises both of the idealist Berkeley, and the sensationalist Condillac" (a French version of Locke from whom both he, Berkeley and Hume ultimately derive). We shall see later how important the passage I capitalized will become. Lenin likes the way Diderot uses the example of a self-conscious piano to explain his views. Such a piano would be able to play on its own the "airs" played upon it. All the problems about the origin of our sensations-- internal, external, etc., Diderot is quoted as saying, would be solved by "a simple supposition which explains everything, namely, that the faculty of sensation is a general property of matter, or a product of its organisation." Now to conclude. This little introduction was just to give some background before Lenin takes up the cudgel against the "Marxist" idealists of his own day. We shall see that they all, to a greater or lesser extent, are influenced by the ideas of the Physicist Ernst Mach (remembered today not for his philosophy but for the Mach number-- object speed divided by the speed of sound: Speed of sound = Mach1, Mach 5 = hypersound, supersonic— the “boom” a jet fighter makes when it it hits this speed). "For the present," then, Lenin says, "we shall confine ourselves to one conclusion: the 'recent' Machists have not adduced a single argument against the materialists that had not been adduced by Bishop Berkeley." Next: Chapter One Section One "Sensation and Complexes of Sensations" AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. Check out the following completed 'Commentary and Analysis' Series from Dr. Riggins:

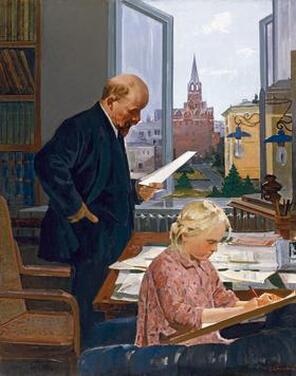

Engels' Anti-Dühring Lenin's Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder Lenin's State and Revolution Short's Mao: A Life 11/17/2021 V. I. Lenin - Materialism & Empirio-Criticism. Commentary and Analysis (1/23). By: Thomas RigginsRead NowThis is a famous work of Lenin's which outlines what Marxist philosophy is all about. It was written over a century ago and we might ask ourselves what is still valid in this classic. Have new philosophical developments in the last hundred years or so made this work outmoded? I'm going to post some reflections on the book, section by section, and anyone who wants to read along and comment is welcome to do so. I hope to post three times a week (Monday, Wednesday and Friday, starting today (Wednesday) with: THE PREFACES: Why did Lenin write this book? He tells us because a number of people calling themselves "Marxists" have been attacking "orthodox" Marxism ("dialectical materialism") and calling it outmoded and wanting to supplement it with new ideas borrowed from bourgeois philosophy. This is still going today in the 21st century as well. Engels is specifically attacked as being "antiquated" and his views on dialectics are said to be a species of "mysticism." None of the books that Lenin attacks are of much interest today and the names of the authors have mostly been forgotten. Perhaps you will recall the name of A.A. Bogdanov and certainly the name Lunacharsky will ring a bell as he later became the first Commissar of Enlightenment (Minister of Education) under the Bolsheviks. Lenin is not opposed to criticism of the views of Marx and Engels. He mentions approvingly Mehring's critique of "antiquated views of Marx" which was undertaken from a dialectical materialist standpoint. Any historians out there reading this are encouraged to send in comments about just what these views were and where Mehring made them as Lenin does not discuss them in the Prefaces. Franz Mehring (1846-1919) was the author of the “classical” biography of Karl Marx (published in 1918 and which all good Communists have read and studied): Karl Marx: The Story of His Life (Karl Marx. Geschichte seines Lebens). This is the "most comprehensive and interesting historical study of Marx”—Louis Althusser. Besides defending the "orthodox" view from "heretics", Lenin also wanted to know what drove ostensible Marxists to bourgeois philosophy. What, he asks, "was the stumbling block to these people" that made them desert the orthodox position. Well, as I mentioned above, in our own day we have a similar problem. Engels is still attacked and efforts are made to cut Marx away from Engels and make Engels some sort of hack. We also have ordinary language Marxists, existentialist Marxists, phenomenological Marxists, postmodern Marxists, etc., etc. This coming Friday I'll look at "In lieu of an Introduction." I'm using Vol. 14 of the CW for the text. The book itself seems to be out of print. You should find a copy online (Lenin Internet Archive is the place to look). If you google "materialism and empirio-criticism" the first entry you get should be an on-line copy of the book so if you don't have a hard copy you can still read it. Ленин живет в наших сердцах AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. Check out the following completed 'Commentary and Analysis' Series from Dr. Riggins:

Engels' Anti-Dühring Lenin's Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder Lenin's State and Revolution Short's Mao: A Life |

Details

Archives

January 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed